Note on the Three Versions of the Text

Cite page (MLA): Wisnicki, Adrian S. "Note on the Three Versions of the Text." Debbie Harrison, ed. In Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. Adrian S. Wisnicki, dir. Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. University of Maryland Libraries, 2017. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/3174f7e5-fce7-42b5-b846-72a0af38fba9.

This note describes the relationship among the four different texts that document Livingstone's experiences in 1871: the 1871 Field Diary, the Unyanyembe Journal (1866-72), the Last Journals (1874), and the letter to Earl Granville (1872d). The note also explores the unique features of the 1871 Field Diary and considers how comparison of the diary to the Unyanyembe Journal and Granville letter provides a fascinating glimpse into the ways that Livingstone hoped to rewrite problematic incidents from this period in his life for public consumption.

Victorian explorers and travellers produced a variety of records to document their experiences in the field. Often they produced these records in stages, with each successive record building on and revising the information contained in previous records. Roy C. Bridges (1987:180) has identified three general categories of such records: “There is the first-stage or ‘raw’ record made as [the explorer] went along, the more considered and organised journal or perhaps letter written during intervals of greater leisure and finally the definitive account of the expedition, usually composed after his return to Europe with a view to publication.” However, adds Bridges, “these categories are not of course absolute and in practice may merge into one another in various ways.” (For more on the critical debate, see Youngs 1994 and Wisnicki 2010.)

Livingstone didn’t live to publish “the definitive account” of his final travels. Rather, Horace Waller posthumously edited and published the Last Journals in 1874 (see Helly 1987; also see The Manuscript). However, Bridges’s categories otherwise offer a useful method for grouping the documents Livingstone produced on his last journey. These documents include first-stage records such as field diaries and notebooks, and second-stage records such as letters and the Unyanyembe Journal (1866-72) into which Livingstone transcribed most of his field diaries. Bridges (1987:181, 184) underscores the value of the “raw,” unadulterated, first-stage records: “Direct and full information on the journey is provided with no later glossing, omission or addition”; as a result, “Livingstone’s notebooks and diaries do sometimes give information which is simply not present at all in published works.”

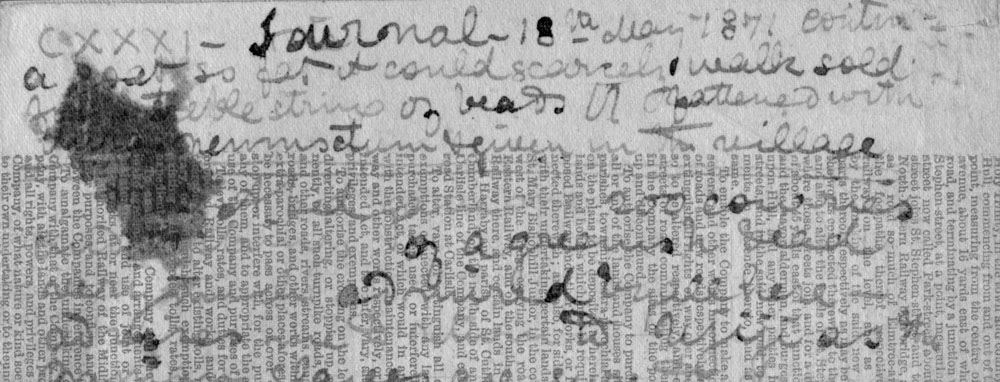

(Top) Natural light and (bottom) processed spectral images of a page of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871f:CXXXI color and intercept), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The material condition of the actual manuscript reveals much about the composition process and the circumstances under which Livingstone produced and transported the text. The processed image here clarifies some of the text beneath the blot at left.

Reference to the texts made available in this edition – the 1871 Field Diary and the corresponding portions of the Unyanyembe Journal (1866-72), the Last Journals (1874), and a passage in an 1871 letter to Earl Granville (1872d; included here as a “bonus” text) – illustrates Bridges’s arguments. Dorothy Helly (1987) has definitively described the range of editorial moves by which Waller transformed the Unyanyembe Journal into the published Last Journals and so helped create the Livingstone we remember today. However, a look at the newly-revealed text of the 1871 Field Diary shows that the distance between this work and the Unyanyembe Journal – let alone the published Last Journals – is much greater than that between the latter two texts.

The 1871 Field Diary offers a candid, unmediated, and often unnarrativized window onto Livingstone’s experiences in the field. The diary reads as much as a Victorian work as it does a fragmentary, modernist record of travel in extreme circumstances. At times the writing is disorganized, at times incoherent, at times Livingstone cycles through a heterogeneous range of narrative modes – offering descriptions of experiences, meteorological observations, native vocabularies, field notes, and drafts of letters in rapid succession. Moreover, the opportunity to read the text of the diary while viewing the images of the manuscript pages – whether natural light or processed spectral images – reveals the intimate link between what Livingstone writes and the way his words appear on the page, for instance, when the particularly heavy blotting of his ink follows a passage where Livingstone notes: “We have rain in large quantity almost every night” (1871f:CVII).

A processed spectral image of a page of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871f:CVII spectral_ratio), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported

The diary also shows Livingstone at a moment of crisis, in circumstances that often get the better of him and lead him into decisions that he would otherwise not make. As a result, when we read the 1871 Field Diary alongside the 1871 letter to Earl Granville and the corresponding segment of the Unyanyembe Journal, we get a fascinating glimpse into the way Livingstone hoped to rewrite problematic incidents and (re)present himself to the public.

Works Cited

[View the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project's full bibliography.]

Bridges, Roy C. 1987. "Nineteenth-Century East African Travel Records with an Appendix on 'Armchair Geographers' and Cartography." Paideuma 33: 179-96.

Helly, Dorothy O. 1987. Livingstone's Legacy: Horace Waller and Victorian Mythmaking. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press.

Livingstone, David. 1866-72. Unyanyembe Journal. 28 Jan. 1866-5 Mar. 1872. 1115. David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1871f. Fragment of 1871 Field Diary (CII-CLXIII). 23 Mar. 1871-11 Aug. 1871. 297b, 297c. David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1872d. Letter to Lord Granville. 14 Nov. 1871. Parliamentary Papers 70 (C-598):10-15.

Livingstone, David. 1874. The Last Journals of David Livingstone in Central Africa, from 1865 to His Death, edited by Horace Waller. 2 vols. London: John Murray.

Wisnicki, Adrian S. 2010. "Rewriting Agency: Baker, Bunyoro-Kitara, and the Egyptian Slave Trade." Studies in Travel Writing 14 (1): 1-27.

Youngs, Tim. 1994. Travellers in Africa: British Travelogues, 1850-1900. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

![Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_013723_0001-new-carousel_0.jpg)

![Processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's "Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal" (Livingstone 1870a:[3] pseudo_v4_BY), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's "Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal" (Livingstone 1870a:[3] pseudo_v4_BY), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000211_0003_pseudoBY_940_by_592-carousel.jpg)

![David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, [1869], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland: CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, [1869], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland: CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_003006_0001-new-carousel_0.jpg)