The Date of the Livingstone-Stanley Meeting

Cite page (MLA): Livingstone, Justin D., and Adrian S. Wisnicki. "The Date of the Livingstone-Stanley Meeting." In Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. Adrian S. Wisnicki, dir. Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. University of Maryland Libraries, 2017. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/bcafb301-2e80-4e89-879a-3210c23efb12.

This essay explores the challenges of dating the famous meeting between Livingstone and Stanley. The essay considers previous critical interpretations, evaluates the additional evidence available from the 1871 Field Diary, outlines the difficulties in reconciling the written accounts of Livingstone and Stanley, and, finally, summarizes the findings and limits of the present analysis.

Introduction Top ⤴

For many years, scholars have debated the precise date of the celebrated meeting between David Livingstone and Henry M. Stanley in Ujiji 1871. Both travellers lost track of the date due to illness, as indeed explorers often did. As a result, Stanley gives the dates as 3 November or 10 November (depending on the text), while the only dating from Livingstone – ambiguous at best – points to 28 October. The 1871 Field Diary does not resolve the issue, but it does provide crucial evidence for further analysis.

Previous Critical Readings Top ⤴

Scholars have already made several attempts to pinpoint the date of the meeting. Much of this work depends on a note from Livingstone in the Unyanyembe Journal (1866-72). In the Journal, Livingstone records that he realized at the beginning of Ramadan (14 Nov. 1871) that he had incorrectly dated his diary. Livingstone indicates that he deduced from Stanley's almanac that he, Livingstone, had run ahead by 21 days. So, for instance, when Livingstone wrote 23 October 1871 in his Field Diary (the day he arrived at Ujiji), it was actually 2 October.

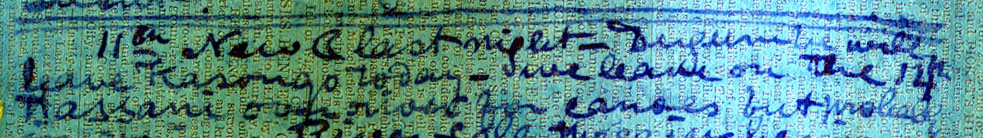

![An image of a page from the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[728]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Images of the Livingstone manuscripts from the David Livingstone Centre are copyright University of Glasgow Photographic Unit. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page from the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[728]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Images of the Livingstone manuscripts from the David Livingstone Centre are copyright University of Glasgow Photographic Unit. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/the-date-the-livingstone-stanley-meeting/liv_016060_0001.jpg)

An image of a page from the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[728]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Images of the Livingstone manuscripts from the David Livingstone Centre are copyright University of Glasgow Photographic Unit. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. This page records Livingstone's meeting with Henry M. Stanley. The date 28 October 1871 appears in the margin and suggests that Livingstone believed the meeting happened on this date. The entry itself is continuous from the previous page, 24 October 1871. Stanley's middle name is given as 'Moreland' rather than 'Morton.'

Cunningham (1985) uses this information to advance one of the most rigorous assessments of the situation. He concludes that Livingstone is only 20 days out and that the actual date should be fixed as 27 October 1871, not the 28 October as Livingstone's diary suggests (Cunningham 1985:37). Cunningham observes that in the final fragment of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871m:[3]), Livingstone writes that 1 November and 3 November were, respectively, Thursday and Saturday (Cunningham 1985:37). Although Livingstone may have been mistaken about the date, the Arabs with whom he travelled would still have known the day of the week, due to the need to observe Jumu'ah prayers.

If this hypothesis is correct, Cunningham argues, then 1 and 3 November are in fact 12 and 14 October, and so Livingstone is 20 days out. Although the evidence of the 1871 Field Diary does support such a reading, as described below, the key issue with Cunningham's argument lies in his numerical correction. If Livingstone was ahead by 20, not 21, days, then a day needs to be added – not subtracted – from 28 October, giving us 29 October 1871 as the day of the meeting.

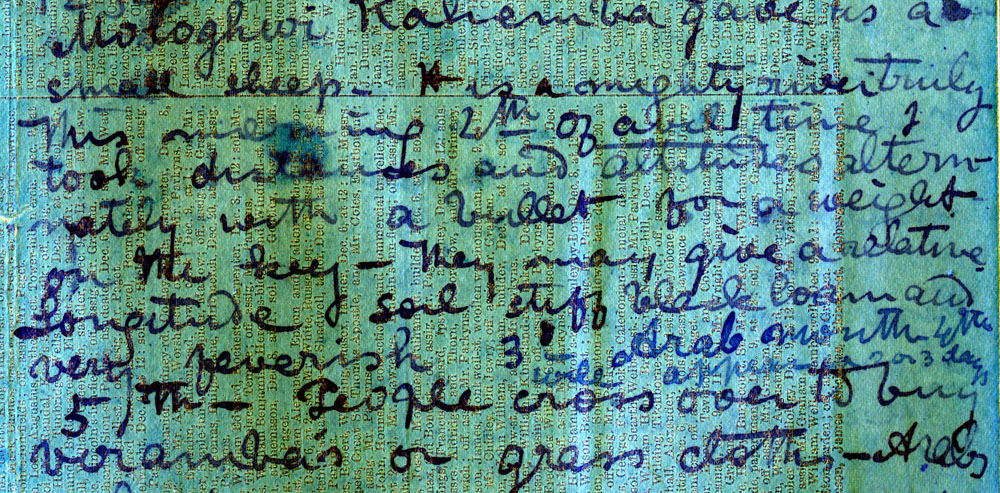

Processed spectral images of two pages of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871f:CXXXVII, CXLIV spectral_ratio), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. This images shows Livingstone's diary entries for 11 June (top) and 10 July 1871 (bottom), both of which record a new moon. The second entry also notes the beginning of the '7th month of Arabs.'

Roy C. Bridges, in response to Cunningham, argues for 29 October 1871. Bridges also observes that it is possible to trace the 20 day error as far back as the beginning of 1871. On 16 January (1871a:LXXVI [v.1]), Livingstone records that "Ramadan ended last night." Since Ramadan ended in 1870 on 24 December, Livingstone's comment indicates that he was at this stage 22 days ahead.

Bridges also sheds light on the confusion of Livingstone's dating by discussing later entries from June and July 1871 (Bridges 1982). In the Unyanyembe Journal, notes Bridges, Livingstone writes that new Arab months began on 11 June and 10 July. Livingstone, adds Bridges, is mistaken about which Arab month it is in each case – in both instances Livingstone is three months ahead because he is counting from the end of the last Ramadan not from the beginning of the Islamic year. Once it becomes clear Livingstone counts Islamic months in this way, the evidence of the Journal does indeed suggest a 20-21 day margin or error, thereby confirming Livingstone's own statement.

Evidence from the 1871 Field Diary Top ⤴

In the 1871 Field Diary, the 11 June and 10 July entries correspond to the Unyanyembe Journal and so confirm that Livingstone was about 20 to 21 days out during these two months. Another passage from 3 April in the 1871 Field Diary, however, helps fill out the picture. This passage shows that in April, Livingstone was 21 – not 20 – days out. The passage also confirms Bridges's suggestion that Livingstone was three months off in identifying the Arab month.

In the entry, Livingstone writes, "This morning 4th of avil time […]" (1871f:CVI). On first reading, contextual evidence suggests that Livingstone has made a mistake and written "avil" instead of "April." The entry follows the beginning of the 3 April 1871 entry and precedes the 5 April 1871 entry. There is also no separate reference to 4 April 1871. Horace Waller – who used C.A. Alington's transcription of this passage (see The Manuscript) – proceeds on this basis and gives this as the opening of the 4 April 1871 entry in the Last Journals (Livingstone 1874).

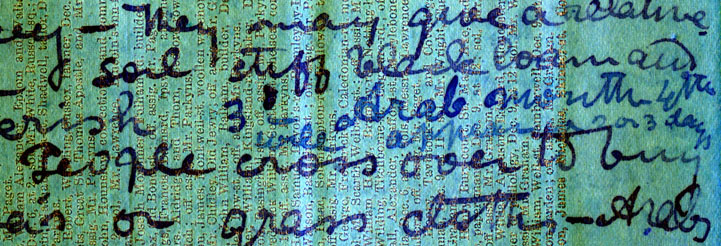

A processed spectral image of a page of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871f:CIX spectral_ratio), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. This image shows a portion of the entries for 3-5 April 1871. The phrase '4th of avil time' appears in the third line here.

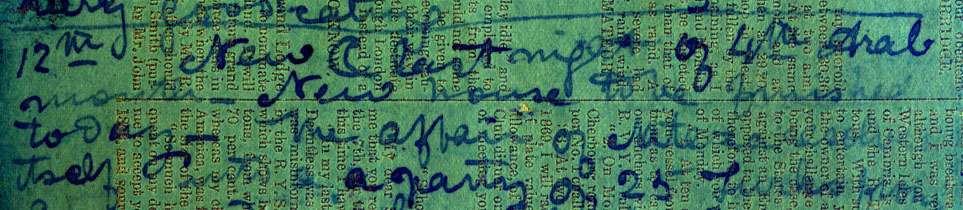

However, there is reason not to accept this reading. Livingstone concludes the entry in which the passage appears with an additional statement: "3rd Arab month 4th will appear in two or three days" (Livingstone 1871f:CVI). An entry made a week later confirms the details of the previous statement: "12 April 1871 New [moon] last night of 4th Arab month" (Livingstone 1871f:CIX).

The concluding statement on 1871f:CVI merits attention for two reasons. First, spectral imaging reveals that this statement has been written in Zingifure ink, while the rest of the page is in iron gall ink. This suggests that Livingstone added the statement at a later date, as, in fact, 1871f:CVI is the last page Livingstone wrote in iron gall ink until 1871f:CXLVI (see Manuscript Composition).

A processed spectral image of a page of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871f:CIX spectral_ratio), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The image shows Livingstone's later addition to the end of the 3 April 1871 entry in his diary. The processed image highlights the use of Zingifure ink, which appears blue while the surrounding text is closer to black.

Second, given these points, it is reasonable to suppose that the after-the-fact addition, which Livingstone took the trouble to make, has reference to the context in which it was made. In other words, in this reading, one possibility is that "4th" in the Zingifure ink addition refers to the prior "4th of avil time" passage, and is a correction of it.

If so, then the "avil" of the latter passage might also be read – not as "April" – but as Livingstone's transliteration of "awwal," or, more fully, "Shahr Al-awwal," an Arabic phrase that means first month of the lunar year. Livingstone's use of this phrase suggests that "avil time" is his way of referring to the Islamic calendar as a whole and so that he initially meant that it was the fourth Arab month, then corrected it to the third.

A processed spectral image of a page of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871f:CIX spectral_ratio), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. This image shows Livingstone's reference to '4th of avil time.'

The first day of the fourth Arab month (Rabi II) in 1871 was 20 June. In other words, when Livingstone wrote 12 April 1871 in his Field Diary and stated that it was the fourth Arab month, the date was in fact 20 June 1871. He was behind in his dates by no less than 69 days! Obviously something is amiss if the text is interpreted in this way. The error is easily rectified if we follow Bridges's suggestion, noted earlier, that Livingstone was counting the months from the last Ramadan rather than from the beginning of the Islamic year (Bridges 1982).

The fourth Arab month on this reading would be the fourth since Ramadan, but the first of the Islamic year, which brings us back to Livingstone's "avil." The first day of the first Arab month (Muharram) in 1871 fell on 23 March. The difference between 23 March and 12 April is 20 days. This calculation in turn supports Cunningham's argument that Livingstone is 20 days out. Yet the matter is not quite put to rest. By this same calculation, 11 June and 10 July (the two other dates in the 1871 Field Diary and 1872 Journal on which Livingstone records the appearance of a new moon) are, respectively, 21 and 20 days out. Over the three months a slight fluctuation appears, but this can be accounted for by the fact that new moons at times go unspotted until one or two days after their first phase.

Reconciling Livingstone and Stanley Top ⤴

Nonetheless, one problem remains. If, based on Livingstone's records, 28 or 29 October seem the likeliest dates, how can this be reconciled with Stanley's accounts? The most contemporary evidence from Stanley comes from a despatch he sent to The New York Herald dated 10 November 1871. In this despatch, Stanley (1970:59) writes that the meeting took place a week earlier, on the 3 November 1871. Yet in How I Found Livingstone, Stanley (1872:274-75) notes that he also lost track of the date and, like Livingstone, did not realize the error until the coming of Ramadan. In his case, adds Stanley, he was seven days ahead. However, the text itself of How I Found Livingstone gives the date as 10 November (Stanley 1872:405), a point that implicitly suggests that Stanley was behind – not ahead – seven days.

A processed spectral image of a page of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871f:CIX spectral_ratio), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The image shows Livingstone's entry for 12 April 1871, which records a new moon and the arrival of the '4th Arab month.'

The situation is confusing indeed. François Bontinck (1979) infers that when Stanley wrote 3 November, he had not yet corrected his dates. If he had, he would have written 27 October, a date that agrees with Cunningham. Yet as we have seen, this date does not agree with the surviving evidence from Livingstone himself. Bontinck also explains that the reason why Stanley gives the date of the meeting as 10 November is that he mistakenly added seven days to his record of 3 November instead of subtracting them, and so this problem, for Bontinck at least, is resolved.

The final turn in the critical argument comes from Tim Jeal. In his recent biography of Stanley, Jeal (2007:505) contends that the 3 November date is already the product of a subtraction. Jeal notes that in an earlier diary, Stanley had given the date of the meeting as 10 November. The date in the despatch, 3 November, was thus seven days earlier and, it appears, had already been revised by Stanley. Yet, if this reasoning is correct, the date of Stanley's despatch becomes dubious. The despatch records the meeting with Livingstone and so must have been written after 14 November when the two men together realized their mistakes in dating. Other evidence presented by Jeal, which is too detailed to recount here, again contradicts the 3 November date in favour of the 10 November date.

| Livingstone Date | Stated Islamic Month | Actual Islamic Month | Actual Gregorian Date | Days Off | |

| 12 April 1871 | "4th Arab month" | Muharram (1st) | 23 March 1871 | 20 days | |

| 11 June 1871 | [6th Arab month] | Rabi I (3rd) | 21 May 1871 | 21 days | |

| 10 July 1871 | "7th month of Arabs" | Rabi II (4th) | 20 June 1871 | 20 days | |

| This table sets out Livingstone's erroneous references to dates and Islamic months, the corrected dates and months, and the number of days by which Livingstone's dates need to be corrected. | |||||

Whatever the case here, Jeal (2007:505-06) ultimately suggests that the details recorded by Stanley are inconsequential and that Stanley fabricated the fact that he had made a mistake in the first place! When Stanley realized that Livingstone believed the meeting to have taken place in late October, Stanley invented the story of his mistake in order to minimize the discrepancy between the two accounts and to make it appear that his, Stanley's, date was closer to Livingstone's than it really was. When it came to writing How I Found Livingstone – the permanent record of the encounter – Stanley opted for what he really believed to be the real date, 10 November 1871. Jeal (2007:506) also adds that Livingstone's "21-day discrepancy is by no means a proven quantity."

The Limits of Interpretation Top ⤴

In other words, the historical and critical record gives us the possible dates of 27, 28, 29 October, and 3 and 10 November for the Livingstone and Stanley meeting. Moreover, although the 1871 Field Diary confirms the text of the Unyanyembe Journal, namely that Livingstone was some 20 or 21 days out in his dating, we can go no further than this because we don't really have a date for the meeting itself from Livingstone.

In the Journal, Livingstone begins to describe Stanley's arrival in the midst of a long entry marked earlier as 24 October (Livingstone 1866-72:[727]). As the entry progresses without break to the next page (1866-72:[728]), Livingstone writes the date 28 October in the margin. The text, however, is continuous from one page to the next, and there is no obvious place for the new entry to begin. In addition, as Bridges astutely notes (1982), Livingstone writes the descriptive text that sets the stage for the meeting in a rather ambiguous manner – "But when my spirits were at their lowest ebb the good Samaritan was close at hand for one morning Susi came running at the top of his speed & gasped out 'An Englishman – I see him'" (1866-72:[727]) – wording that opens possibilities rather than closes them, especially the reference to "one morning."

As a result, we can go no further than this, at least without the discovery of additional evidence. The 1871 Field Diary, although it advances the critical discussion, cannot close it. The last entry in the 1871 Field Diary (1871m:[3]) bears a date of 3 November, which, when corrected, gives us either 13 October (a difference of 21 days) or 14 October (20 days, Cunningham's argument). The Diary, therefore, brings us to the doorstep of the celebrated meeting and its actual date, but no further.

Works Cited Top ⤴

[View the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project's full bibliography.]

Bontinck, François. 1979. "La Date de la Rencontre Stanley-Livingstone." Africa: Rivista Trimestrale di Studi e Documentazione dell'Istituto Italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente 34 (3): 225-41.

Bridges, Roy C. Private Correspondence. 1982. “Letter to Ian Cunnningham,” August 23.

Cunningham, Ian C., ed. 1985. David Livingstone: A Catalogue of Documents: A Supplement. Edinburgh: National Library of Scotland for the David Livingstone Documentation Project.

Jeal, Tim. 2007. Stanley: The Impossible Life of Africa's Greatest Explorer. London: Faber and Faber, Ltd.

Livingstone, David. 1866-72. Unyanyembe Journal. 28 Jan. 1866-5 Mar. 1872. 1115. David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1871a. Fragment of 1870 Field Diary (LXXVI). 16 Jan. 1871. 297b. David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1871f. Fragment of 1871 Field Diary (CII-CLXIII). 23 Mar. 1871-11 Aug. 1871. 297b, 297c. David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1871m. Fragment of 1871 Field Diary. 23 Oct. 1871-3 Nov. 1871. Waller MSS. Afr. s. 16.1, f. 172. Bodleian Library. Weston Library, Oxford, England.

Livingstone, David. 1874. The Last Journals of David Livingstone in Central Africa, from 1865 to His Death, edited by Horace Waller. 2 vols. London: John Murray.

Stanley, Henry Morton. 1872. How I Found Livingstone: Travels, Adventures, and Discoveries in Central Africa; including Four Months' Residence with Dr. Livingstone. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington.

Stanley, Henry Morton. 1970. Stanley's Despatches to the New York Herald. Edited by Norman R. Bennett. Boston: Boston University Press.

![Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_013723_0001-new-carousel_0.jpg)

![Processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's "Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal" (Livingstone 1870a:[3] pseudo_v4_BY), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's "Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal" (Livingstone 1870a:[3] pseudo_v4_BY), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000211_0003_pseudoBY_940_by_592-carousel.jpg)

![David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, [1869], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland: CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, [1869], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland: CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_003006_0001-new-carousel_0.jpg)