Livingstone's Manuscripts in the Digital Age

Cite page (MLA): Wisnicki, Adrian S. "Livingstone's Manuscripts in the Digital Age." Megan Ward, ed. Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. University of Maryland Libraries, 2015. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/d3443f49-2d3b-45ee-b815-d0a762ab0d8e.

This essay traces the history of documenting and assembling Livingstone's surviving manuscripts through the Livingstone Documentation Project (1973-85), followed by the ongoing efforts of Livingstone Online (2004-present) to bring digital editions of these manuscripts to a global audience.

Until the 1970s, no one knew the full extent of Livingstone’s surviving manuscripts. A number of particularly well known libraries and archives in Britain and Africa had substantial holdings of original Livingstone manuscripts. In addition, a handful of collections of letters and other items had emerged over the years, notably a series edited by Isaac Schapera, who focused on Livingstone’s writings from his first sojourn in Africa (1959, 1960, 1961, 1963, 1974). Some letters had also appeared in print in a variety of sources that went back to the nineteenth century. Yet Livingstone had been one of the most prolific travelers to visit nineteenth-century Africa. Anyone who took a serious interest in his legacy recognized the need for a full enumeration of his manuscripts.

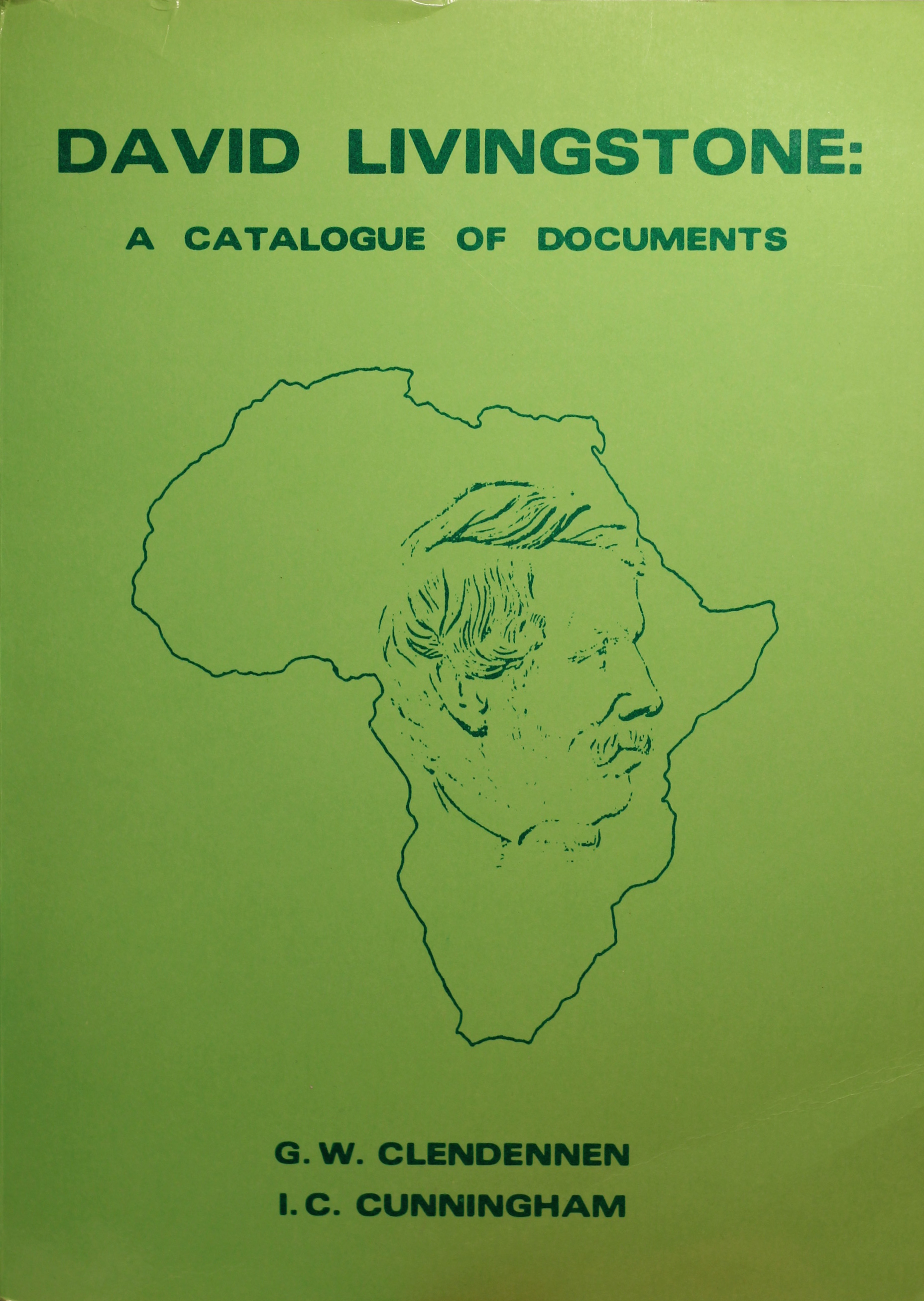

The Livingstone Documentation Project (LDP) emerged to meet this need. Although LDP did not originate at a single moment, it first took substantial shape at a 1973 University of Edinburgh seminar marking the centenary of Livingstone’s death. At that seminar, scholars noted the need for a catalogue of all Livingstone manuscripts, the creation of a central collection of original and photocopied materials, and, over time, the publication of critically-edited collections. Work focusing on the first two objectives got underway in earnest over the next few years. The project’s efforts resulted, ultimately, in the monumental publication of David Livingstone: A Catalogue of Documents (1979) edited by Gary Clendennen and Ian Cunningham, followed by a supplement a few years later (Cunningham 1985) plus a history of the project (Clendennen and Casada 1981).

| (Left; top in mobile) G.W. Clendennen and I.C. Cunningham, David Livingstone: A Catalogue of Documents (Edinburgh: National Library of Scotland for the David Livingstone Documentation Project, 1979). Open Government License v3.0; (Right; bottom) I.C. Cunningham, David Livingstone: A Catalogue of Documents; A Supplement (Edinburgh: National Library of Scotland for the David Livingstone Documentation Project, 1985). Open Government License v3.0 |

The Catalogue for the first time brought a number of key points to light. First, it confirmed that Livingstone had indeed been a prolific writer, probably more so than anyone had imagined. Second, it revealed that his original manuscripts as well as published versions of manuscripts that no longer survived still existed in vast abundance. The original Catalogue enumerated the following: over 2000 letters, 11 substantial journals, 39 field diaries of various sorts, 18 notebooks, 30 papers and reports, and almost 200 other miscellaneous items. Third, the Catalogue showed that these manuscripts were indeed scattered around the world, with some ninety repositories being listed between the Catalogue and its supplement that encompassed Britain, Portugal, France, New Zealand, the United States, and several countries in Africa. Many, many other items remained in unknown private hands. The project, which continued until April 1985, resulted in a significant portion of these manuscripts, either in original or copy, being brought together at the National Library of Scotland.

In 2004, Livingstone Online took up the work of the documentation project. Although Livingstone Online began with modest aims, each successive project stage enlarged the scope and objectives of the site. Between 2004 and 2013, the team of Livingstone Online acquired digital image copies (5000 image files) and/or created rigorous scholarly transcriptions of some 700 letters and and a variety of other items as well as multispectral editions of Livingstone’s 1870 and 1871 Field Diaries. The team also identified some thirty previously uncatalogued items, produced an integrated digital version of the original print Catalogue and its supplement, and acquired nearly 500 images of objects related to Livingstone’s travels or of repositories holding his manuscripts.

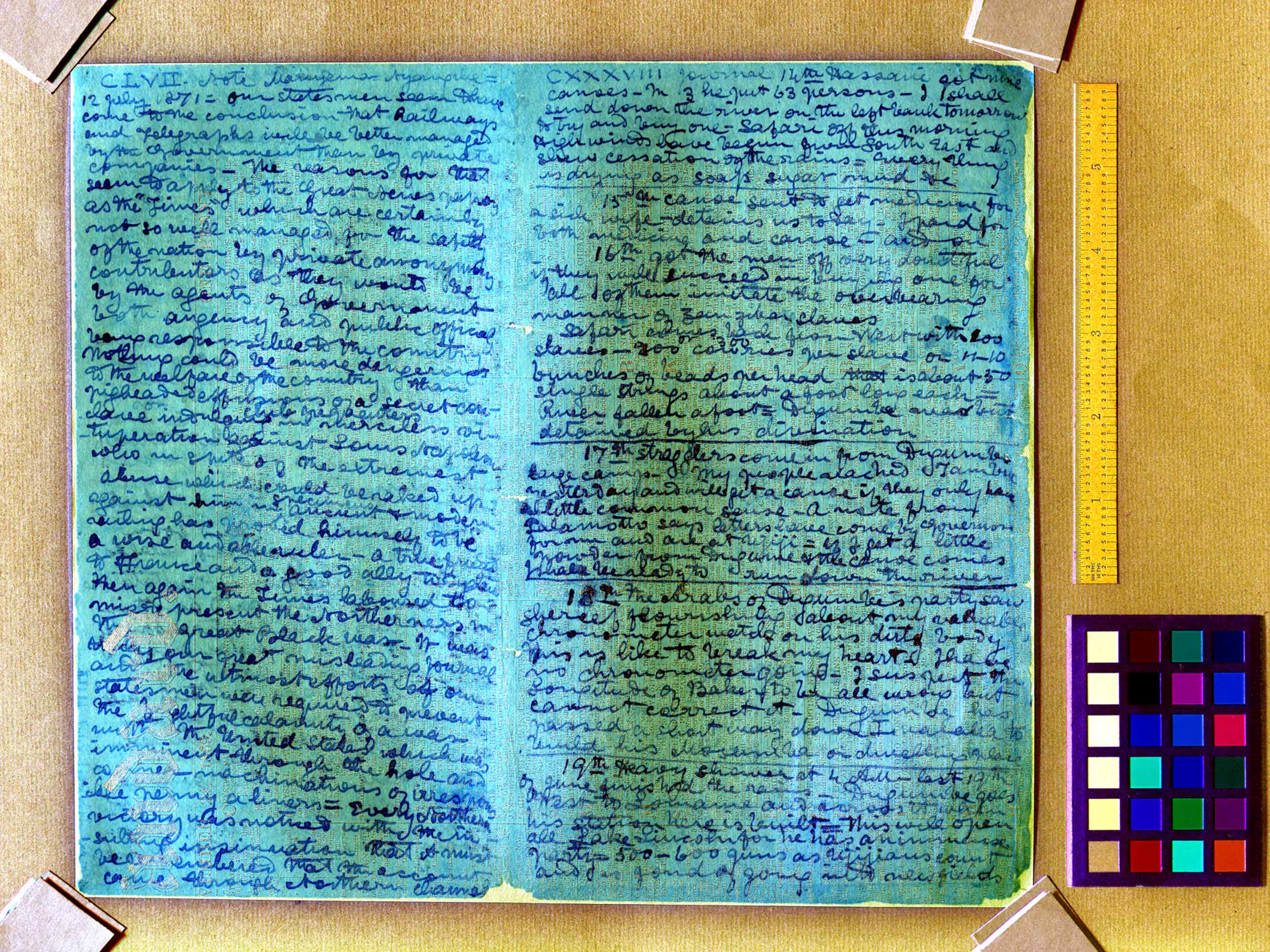

A processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and, as relevant, Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported

The Livingstone Online Enrichment and Access Project (LEAP, 2013-17) has further extended this work, collecting information on some 100 previously uncatalogued items, including maps, and adding 5000 new manuscript pages that cover all phases of Livingstone’s career. These encompass the surviving 850 page draft of Missionary Travels and nearly all the diaries, journals, notebooks, maps, and other items associated with Livingstone’s last travels (1866-73), possibly the most comprehensive and diverse surviving collection of manuscript documents related to any single nineteenth-century British expedition to Africa. Various site features and enhancements, detailed elsewhere on our site, enable interaction with and comparative study of these manuscripts in a manner never before possible.

As a result, today Livingstone Online provides unprecedented global access to a significant portion of Livingstone’s manuscript legacy. Through partnerships with the David Livingstone Centre, the National Library of Scotland, and other archives with Livingstone holdings, our site seeks to introduce a new generation of audiences with diverse interests to this legacy. And there is still much room to grow – including further multispectral study of particular documents and the addition of many, many still-undigitized manuscripts. In addition, initiatives left undone by the original documentation project are yet to be developed: the full enumeration of Livingstone’s surviving maps and the ever-alluring search for previously unknown Livingstone manuscripts in Angola, Mozambique, Tanzania, Malawi, and elsewhere around the world. If you know of any such manuscripts, please drop us a note.