Field Diary III: An Overview

Cite page (MLA): Ward, Megan, and Adrian S. Wisnicki. "Field Diary III: An Overview." In Livingstone's Final Manuscripts (1865-1873). Megan Ward and Adrian S. Wisnicki, dirs. Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. University of Maryland Libraries, 2018. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/71ed5af0-2b30-4cb6-9c86-95af8a77a565.

This page introduces Field Diary III, which is part of our critical edition of Livingstone's final manuscripts (1865-73). The first part of the essay summarizes Livingstone's emerging concerns with food scarcity, slavery, and struggles for authority. The essay then moves on to analyze how Livingstone's composition methods differ in this diary from the previous two.

[View the critical edition or download a basic reading copy of Field Diary III.]

As Livingstone and his men travel further away from the coast and begin to head towards Lake Nyassa, Livingstone first encounters the problems that would dog him for the remainder of his last journey: food scarcity, the slave trade, and mutiny among his men. Although Livingstone first notes the group’s hunger early in the diary, they receive food from a friendly chief. As men trek further into the interior of Africa, however, it becomes more and more difficult to procure enough food. Though Livingstone repeatedly sends his men off to buy food with cloth, they often come back empty-handed or with inadequate supplies.

Early on, Livingstone shrugs this off – “these are the little troubles of travelling & scarcely worth mentioning” – yet because they repeatedly “get no food except a little green Sorghum,” shortage of food becomes a recurrent topic throughout the diary (Livingstone 1866b:[8], [9]). Many of the local African words Livingstone learns and records during this period have to do with food, including sugar, pepper, and cooking utensils.

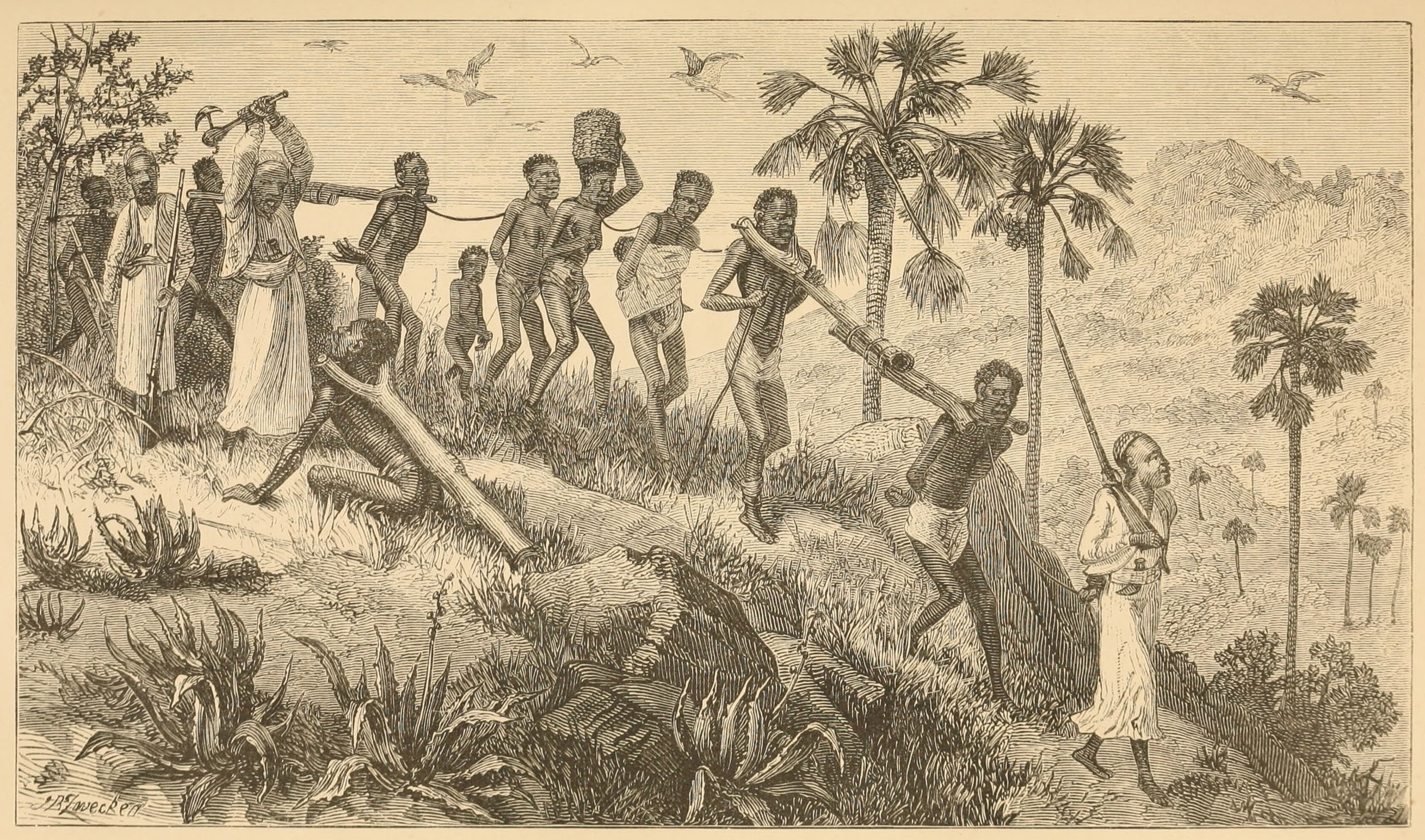

Slavers Revenging Their Losses. Illustration from the Last Journals (Livingstone 1874,1:opposite 56). Courtesy of Internet Archive.

The food shortage is caused in part by the slave trade, as the slavers have cornered the market with their lavish payments. Livingstone encounters more and more evidence of the slave trade as his journey continues, from a taming sticks early on (used to keep slaves yoked together) to the bodies of slaves tied to trees and left to die when they were too weak to keep up with the group.

The later entries in this diary include scathing indictments of African complicity with slaving, as they purportedly captured members of other ethnic groups in retaliation and sold them to the Arabs for cloth (Livingstone 1866b:[95]). Livingstone concludes, “it is a most pernicious error of the Ethnographers that savages are influenced by fear alone – this may possibly be the case in Australia but it is not true of Africans” (Livingstone 1866b:[103]). In this, he suggests that Africans perpetuated their own destruction in the slave trade through greed and local conflicts.

![An image of a page of Field Diary III (Livingstone 1866b:[52]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of Field Diary III (Livingstone 1866b:[52]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/field-diary-iii-overview/liv_000003_0052-article.jpg)

An image of a page of Field Diary III (Livingstone 1866b:[52]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported

During this time, Livingstone also encounters the struggles for authority that would continue for the rest of this journey and these, too, happened in relation to the food shortage. Suffering from hunger and fatigue, the Sepoys (Indians serving in the British army whom Livingstone recruited in Bombay) refuse to walk “on pretence of being unable to march” (Livingstone 1866b:[27]). For the rest of the diary, Livingstone records his attempts to first ignore, then threaten the Sepoys, recognizing that “the chief difficulty at present arises from famine” (Livingstone 1866b:[54]).

This diary takes the same form as the two before it, a 153mm tall x 96 mm wide x 9 mm thick side-bound hardback notebook bound in green silk. And as in previous field diaries, Livingstone writes from both ends of the diary at once, starting at the opposite end upside down. Livingstone begins in blue pencil but shifts to grey pencil starting on 1 June 1866. This diary contains an unusually large number of drawings, mostly of tattoos and mountains, though it also contains other maps and jottings.

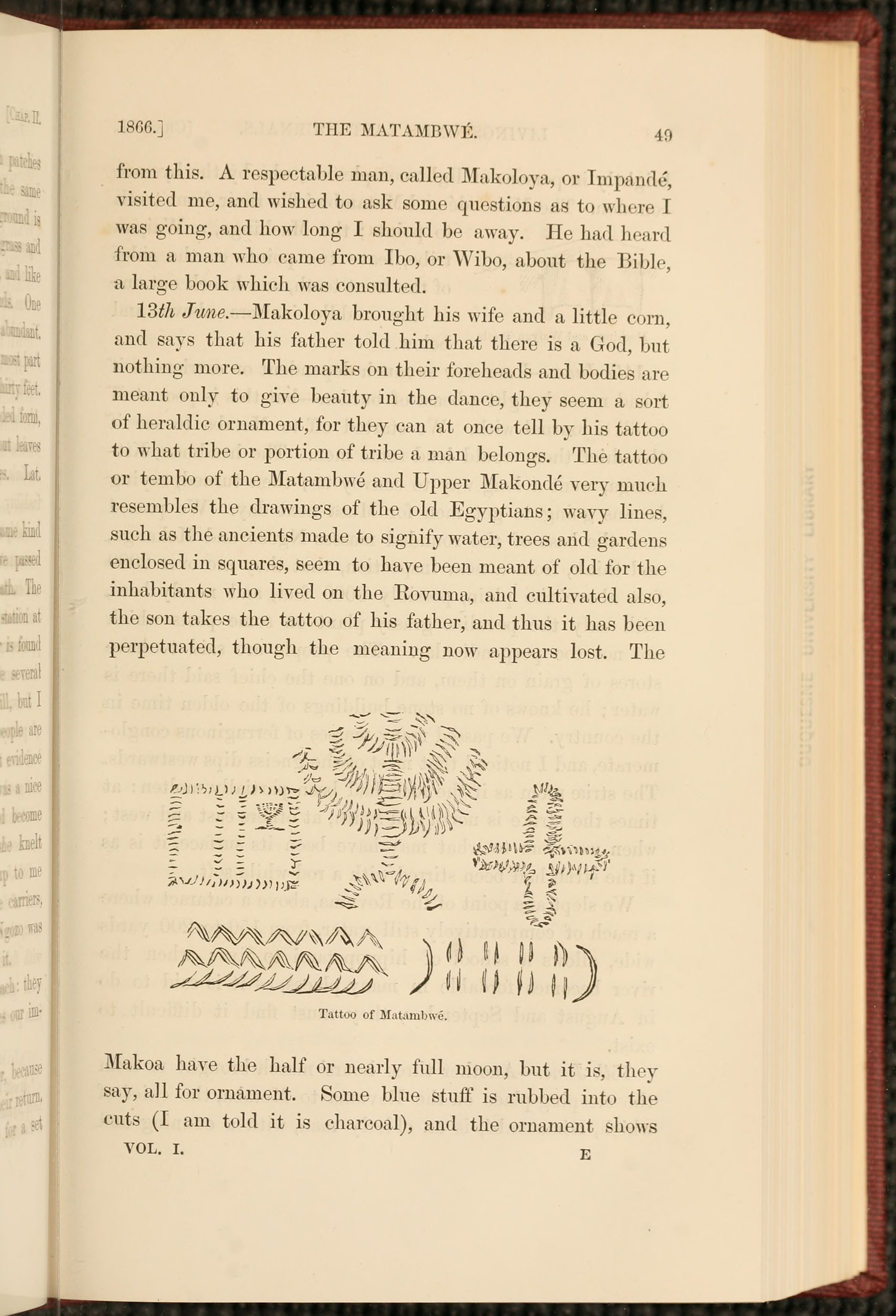

| (Left; top in mobile) An image of a page of Field Diary III (Livingstone 1866b:[33]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. (Right; bottom) Tattoo of Matambwe. Illustration from the Last Journals (Livingstone 1874,1:49). Courtesy Internet Archive. These two images present some of the same illustrations and so allow comparison between Livingstone's original drawings and the revised versions posthumously published in the Last Journals. |

In addition, shifting away from the more strictly narrative record of travel, the diary also contains many observations about African culture, including many drawings of tattoos and notes on their meaning, describing them as “a sort of heraldry” (Livingstone 1866b:[37]). Livingstone also records local agriculture, topography, food preparation methods, pottery, and practices in sickness.

More than the previous two notebooks, Field Diary III appears to function both as a reference work in the moment as well as a record for future writing. In addition to the usual notes about wages and loads to carry, Livingstone takes down first-hand information from Africans. Toward the end of the journal he labels one map “Chirikaloma’s account of North end of Lake journey of Kandulo" (Livingstone 1866b:[104]).

| Images of two pages of Field Diary III (Livingstone 1866b:[17], [32]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The page at left (top in mobile) includes the name of a chief as written by him in Arabic and as transliterated by Livingstone. |

Livingstone also asks a chief to write his name on the facing page, which he does in Arabic. Livingstone then transliterates the name as “Bonārie o boana salale” and notes the language as “Somalie,” thereby underscoring the diverse African populations that Arab expansion helps escort into east and central Africa (Livingstone 1866b:[17]). The moment also shows a shift toward Livingstone’s eventual use of the field diaries as both reference and record of his experiences, shaped and marked by those around him.

![John Murray III and Anon., David Livingstone - Boat Scene (Painted Magic Lantern Slide), [1857], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND. John Murray III and Anon., David Livingstone - Boat Scene (Painted Magic Lantern Slide), [1857], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND.](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_014067_0001-carousel.jpg)

![Image of two pages from Livingstone's Field Diary XVI (Livingstone 1872h:[2]-[3]). CC BY-NC 3.0 Image of two pages from Livingstone's Field Diary XVI (Livingstone 1872h:[2]-[3]). CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000016_0003-carousel.jpg)

![David Livingstone, Map of Lakes Nyassa and Shirwa [1864?], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND; Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson, CC BY-NC 3.0 David Livingstone, Map of Lakes Nyassa and Shirwa [1864?], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND; Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson, CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000077_0001-tile.jpg)

![An image of a page of Field Diary III (Livingstone 1866b:[33]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of Field Diary III (Livingstone 1866b:[33]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/field-diary-iii-overview/liv_000003_0033-article.jpg)

![An image of a page of Field Diary III (Livingstone 1866b:[17]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of Field Diary III (Livingstone 1866b:[17]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/field-diary-iii-overview/liv_000003_0017-article.jpg)

![An image of a page of Field Diary III (Livingstone 1866b:[32]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of Field Diary III (Livingstone 1866b:[32]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/field-diary-iii-overview/liv_000003_0032-article.jpg)