Creating the 1870 Field Diary

Cite page (MLA): Wisnicki, Adrian S., et al. "Creating the 1870 Field Diary." In Livingstone's 1870 Field Diary. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. University of Maryland Libraries, 2017. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/64a38b96-79b8-47a9-99d6-34c9838a0980.

This section, the first of a six-part sequence, begins a comprehensive account of the 1870 Field Diary as a constructed and preserved object, and explores the initial steps in the creation of the diary.

Introduction Top ⤴

As a material and visual object, the 1870 Field Diary differs both from Livingstone's other field diaries and from similar diaries kept by other Victorian travelers to Africa and elsewhere.

Usually, travelers of the era recorded their impressions in the field in bound journals or notebooks – such as Livingstone’s Unyanyembe Journal (1866-72) or the small “pocket-books” (Waller, in Livingstone 1874:1,iv) that Livingstone used for all other periods of his final travels (1866-73) – or, at minimum, used unmarked leaves of paper. The 1870 Field Diary, by contrast, consists of a series of reused, heterogeneous, and unrelated printed and handwritten texts over which Livingstone has written his entries.

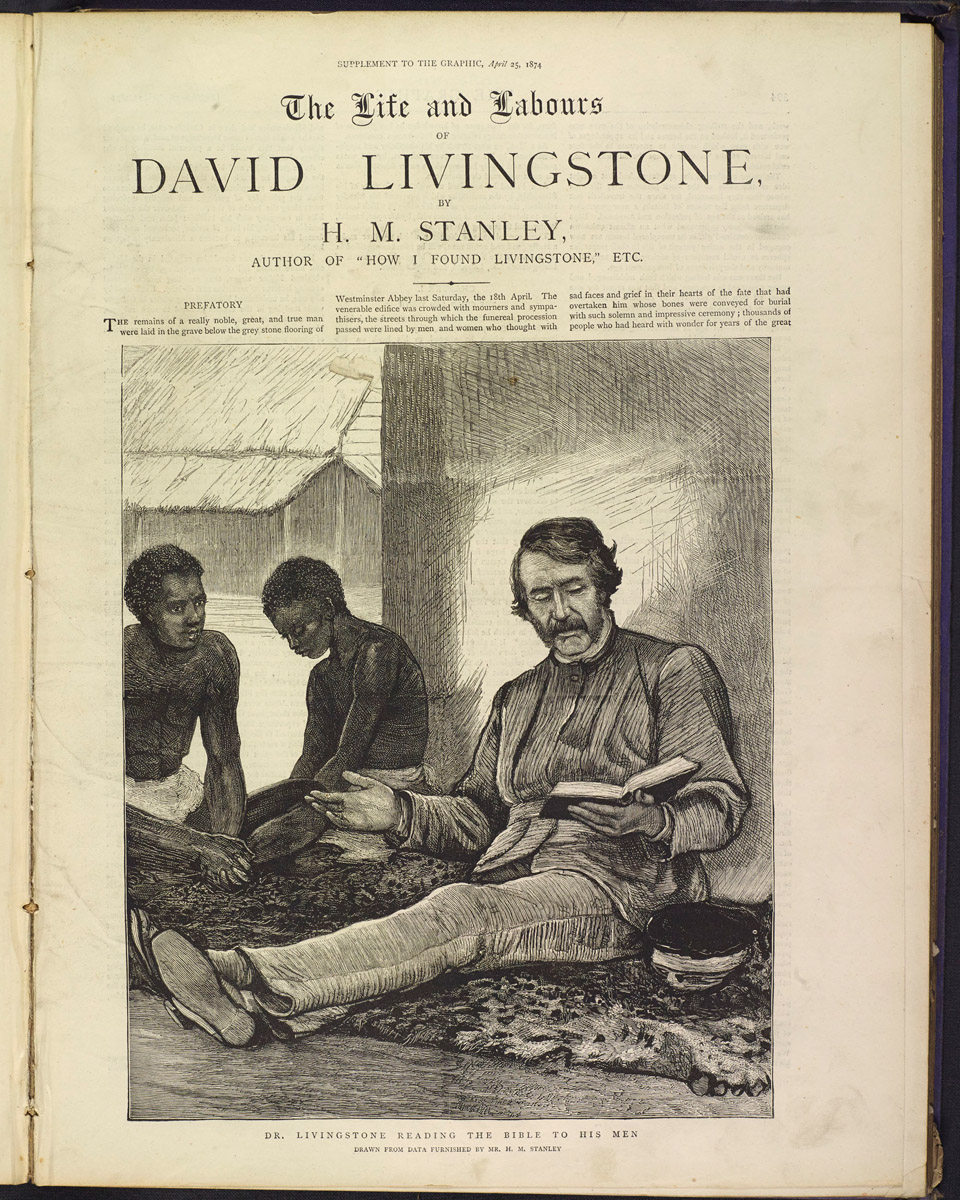

"Dr. Livingstone reading the Bible to his men. Drawn from data furnished by Mr. H.M. Stanley." Illustration from Supplement to The Graphic, 25 April 1874, 393. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. The image presents an idealized Victorian representation of Livingstone and some of his African attendants, drawn from Stanley's perspective. In Livingstone's case, for instance, the narrative of the 1870 Field Diary offers a rather different picture of explorer's physical health during the general period in question. From the undertexts that Livingstone used to create the 1870 Field diary, we also know that his reading during this period was more varied than just the Bible.

Livingstone’s complex decisions and practices in constructing the diary also contribute to its unique status as a nineteenth-century field record, one that serves as an iconic text of Victorian exploration under extreme circumstances. Careful study of the decisions and practices promises to enrich our understanding of Livingstone, his cultural contexts in both Britain and Africa, and, more broadly, the creation of nineteenth-century travel accounts in at least three ways.

First, the material and textual dimensions of the diary open a window onto Livingstone's circumstances in the field – his state of mind; his practices as an observer and diarist; the options available to him as a writer for British culture but one spatially isolated from that culture by virtue of his travels; and the impact of the African, Arab, and, to a lesser extent, Indian populations on his compositions.

Second, Livingstone's choices in constructing the diary also provide insight into nineteenth-century cultural and scientific expectations for the form such field notes should or could take. What were these expectations? Given his limited resources, how does Livingstone maintain a sense of scientific practice in his notes? And what might these tactics tell us about his specific priorities as a writer?

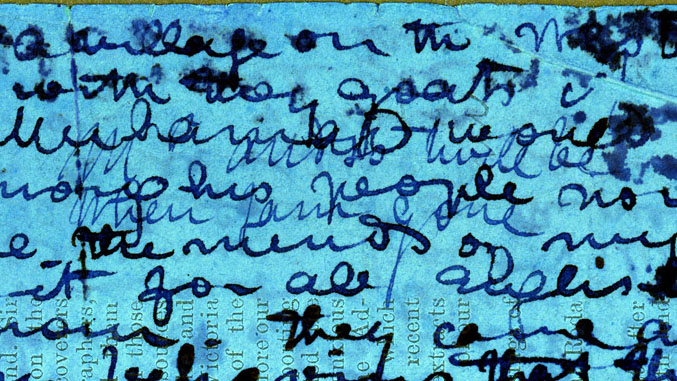

Animated spectral image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary, second gathering (Livingstone 1871b:LXXXII color_raking). Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The image shows the relationship between visible page features and underlying folds and creases.

Finally, the 1870 Field Diary is a historical object, one that Livingstone carried with him to his death, that traveled after his death from the center of Africa to Britain, that appeared in edited form as part of the Last Journals (1874), and, finally, that survived, more or less intact, to the present day. What can the leaves of the diary tell us about this sequence of events?

This section of the edition develops a comprehensive account of the 1870 Field Diary as a constructed and preserved object, toward beginning a response to the above questions. In doing so, we explore the material creation of the diary, the structure that Livingstone (and, later, others) imposed on the text, prominent textual features, and, finally, the passage of the diary across hands, time, space.

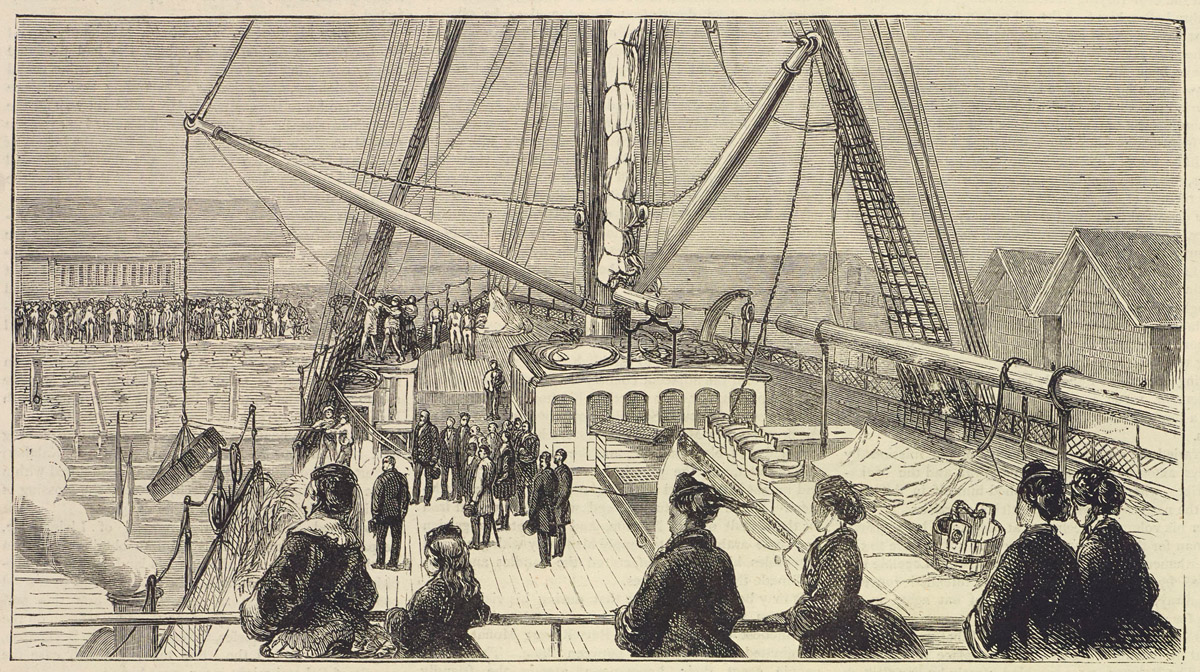

"Removing the body from the 'Malwa' to the tender 'Queen.'" Illustration from Supplement to The Graphic, 25 April 1874, 396. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. Livingstone kept the 1870 Field Diary with him until his death in 1873. The diary then traveled with Livingstone's body from central Africa (present-day Zambia) to Britain where Livingstone's family eventually distributed the diary's pages among a small number of archives.

The first two parts in our study of the "state of the manuscript" foreground Livingstone’s choices in creating the manuscript, with spectral images used only as necessary to illustrate key points. The last four parts, in turn, spotlight the diary’s long-term history and rely on spectral images to a much greater degree in order to outline Livingstone’s decisions in revising the text and the subsequent confluence of events that have resulted in the configuration and preservation of the manuscript as it stands today.

(Note: The name "1870 Field Diary" is a slight misnomer as the dates of the diary actually run from 17 August 1870 to 22 March 1871. However, there is no accepted collective name for the sequence of fragmentary texts that constitutes this diary, so we have used the name "1870 Field Diary" in order to distinguish this diary from the "1871 Field Diary," which is the subject of separate critical edition by the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project.)

Livingstone’s Undertexts Top ⤴

Livingstone had run short of unmarked writing paper when he began to compose his 1870 Field Diary in August of that year. As a result, he reused a variety of documents (at least six) to record his diary entries and wrote his entries over the pre-existing printed and handwritten text on these documents (which we call undertexts or source texts).

The documents used for the 1870 Field Diary include (in order of use):

1) an anonymous review essay on Irish church history books from the Quarterly Review, April 1866 (Livingstone 1870b);

2) a July 1866 letter to Livingstone from someone named Gorbello[?] (Livingstone 1870c);

3) Arthur Penrhyn Stanley’s The Bible: Its Form and Substance, 1863 (Livingstone 1870e/1870f/1870i/1870j/1870k);

4) Samuel White Baker’s “A Map of the Albert N’yanza” from the Journal of the Royal Geographical Society, 1866 (Livingstone 1870h);

5) an article (proof) by George Birdwood from the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bombay, 1863 (Livingstone 1871a/1871b); and

6) the Pall Mall Budget , 21 August 1869 (Livingstone 1871e).

Collectively, these documents provide a snapshot of some of Livingstone’s reading during this period.

-article-1200.jpg)

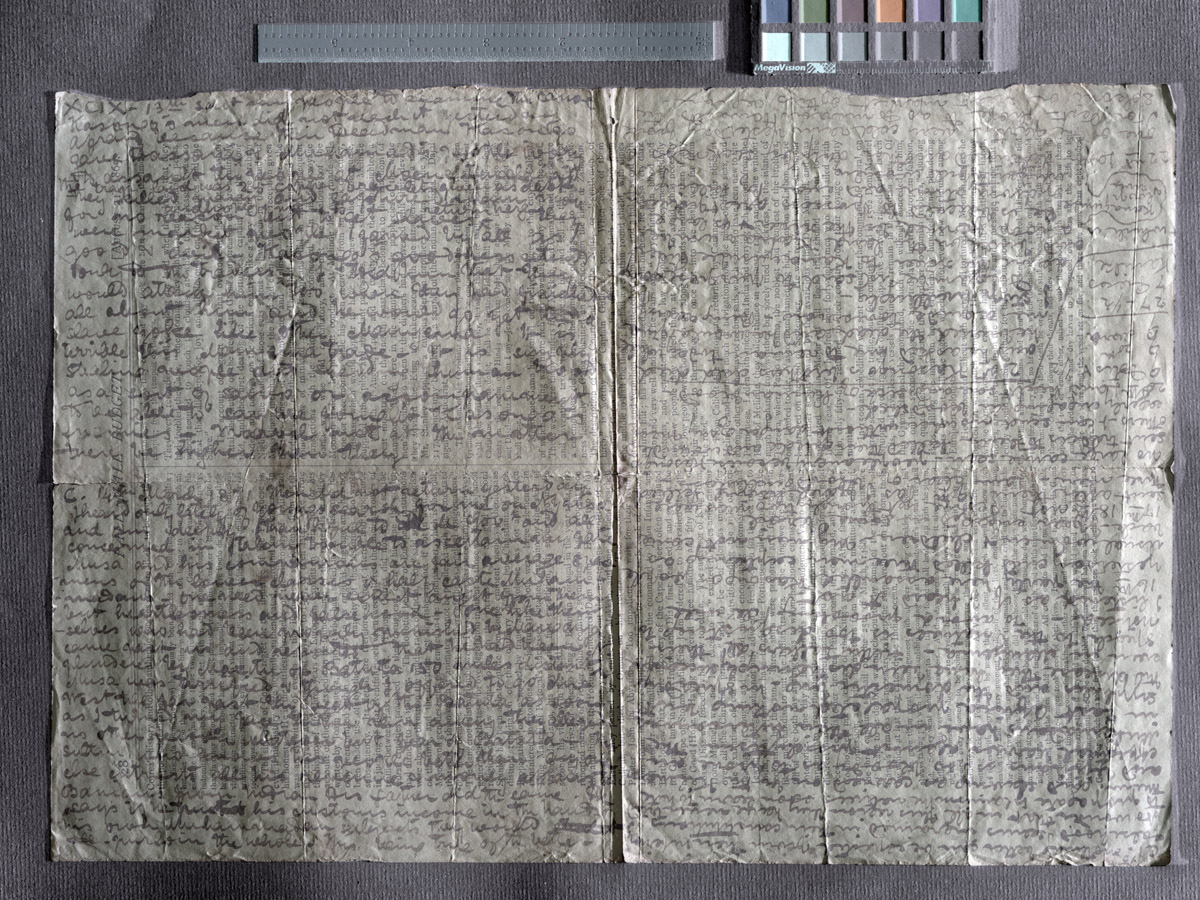

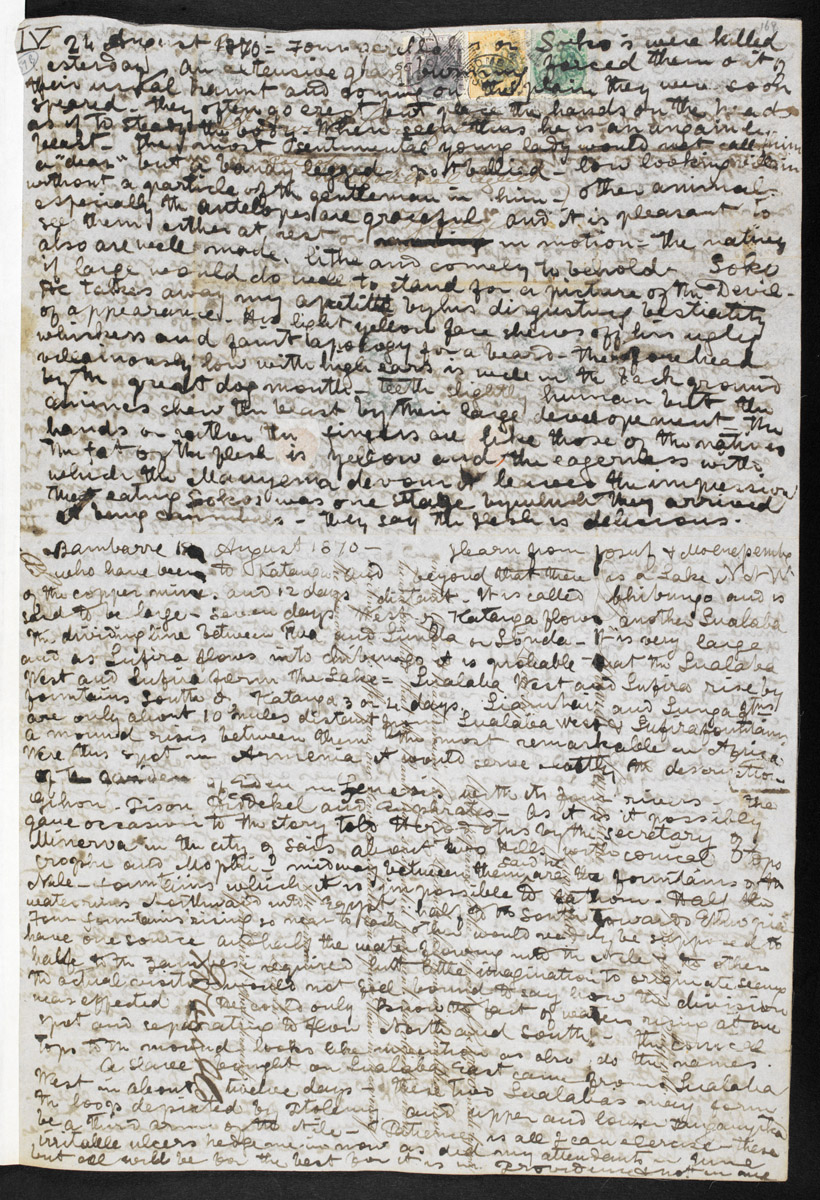

An image of four pages of the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871e:XCIII, XCIV, XCI, XCII). Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. This processed image suppresses Livingstone's writing and foregrounds the printed text of the Pall Mall Budget.

In composing his diary, Livingstone sometimes uses all the leaves of the given document (Livingstone 1870c, 1870h, 1871a/1871b). In other cases, he only uses a selection of leaves from the item (Livingstone 1870e/1870f/1870i/1870j/1870k, 1871e). In the case of 1870b, Livingstone includes only the margins of the leaves, which he has cut off and tied together into a small booklet. It is not possible to give an account of the leaves (or leaf sections) from the above texts that are not accounted for in Livingstone’s diary, as the missing leaves appear not to have survived. Livingstone may have used these missing leaves to compose other documents.

The 1870 Field Diary may also have included source texts beyond those cited above. We do not know if another gathering preceded what we now call the first gathering (Livingstone 1870b; see Gatherings). Pages V-IX and XV-XVI of the second gathering are missing, although these pages appear to have returned to Britain in the nineteenth century and served as the basis of a transcription by Agnes Livingstone (see Livingstone 1870d and 1870g). Livingstone, presumably, wrote these diary pages over reused documents, as he did those pages that precede and follow them in sequence. Finally, the National Archives of Zimbabwe hold one fragment of the diary (dated 25 August, 4 October, 8 October 1870), the original of which we were not able to consult for this edition due to budget restrictions, but that Clendennan and Cunningham (1979:276) cite as being written over a letter.

(For additional discussion of Livingstone’s reuse of source texts for his own texts during 1870 and 1871, see Clendennan and Cunningham 1979:346-47 and our critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary.)

Bonus: Download a spreadsheet that sets out the relationship of Livingstone’s diary to its underlying source texts in detail.

Double-bonus: Download unmarked PDF copies (50.7 MB) of source texts #1, 3, and 5.

Gatherings Top ⤴

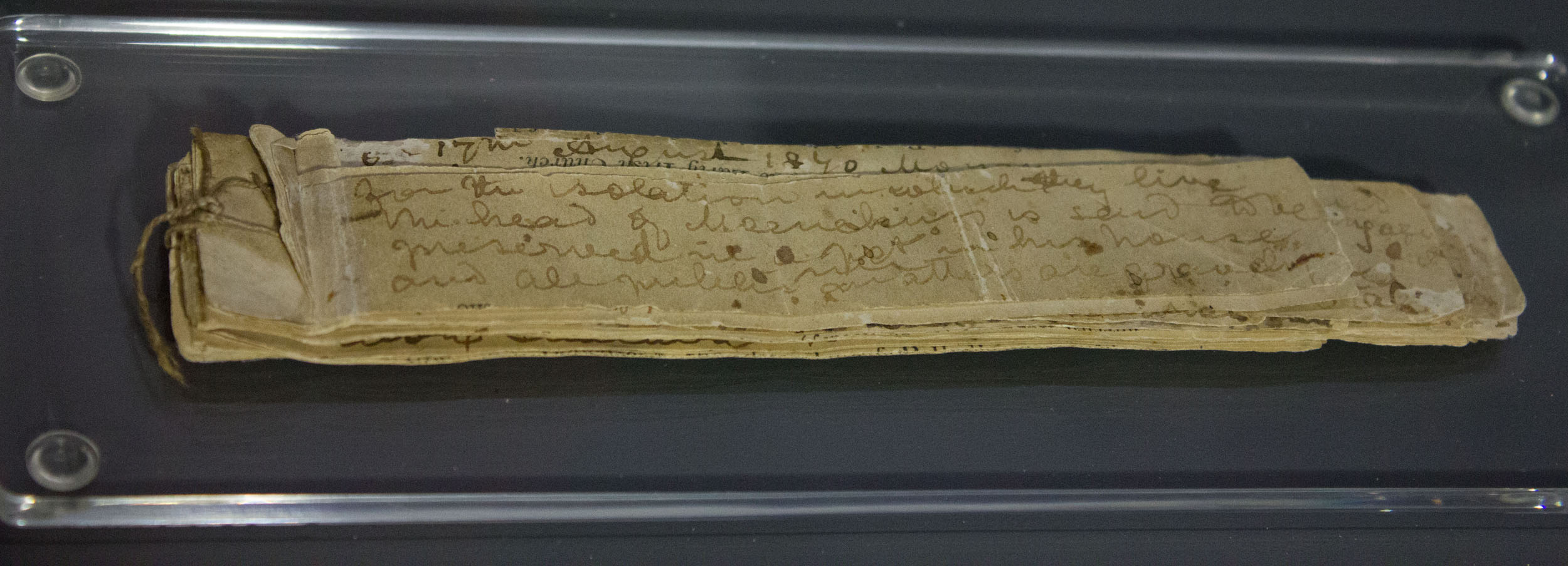

The leaves of the 1870 Field Diary divide into two main gatherings. The first gathering comprises a small booklet constructed from the snipped page margins of a review essay from the Quarterly Review (Livingstone 1870b). The leaves of the first gathering are bound together on the left side with twine tied in a knot, visible in our images. The second gathering comprises the remaining leaves of the diary, i.e., the bulk of the text (Livingstone 1870c, 1870e, 1870h, 1870i, 1870j, 1870k, 1871a, 1871b, 1871e). Although unbound, the leaves of the second gathering form a sequence, and Livingstone has numbered the rectos and versos of these leaves with Roman numerals.

David Livingstone's 1870 Field Diary, first gathering (Livingstone 1870b), on display at the David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre, Scotland. Livingstone created this gathering by binding together the snipped page margins of an article from the Quarterly Review. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Angela Aliff. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported

The first gathering consists of 35 leaves, each of which contains a page on the recto and verso, for a total of 70 pages. This gathering is incomplete as the first page begins mid-sentence, suggesting that one or more preceding leaves are missing. In addition, Agnes’s transcription of the 1870 Field Diary, which survives in Oxford’s Bodleian Library and is available in full from Livingstone Online, suggests that the pages currently missing from the beginning of this gathering were already missing by the time the diary reached Agnes since she omits them in her transcription. However, the text of the gathering is internally continuous, indicating that no leaves from the middle are missing. Likewise, the gathering ends with Livingstone’s signature, suggesting that this was the final leaf.

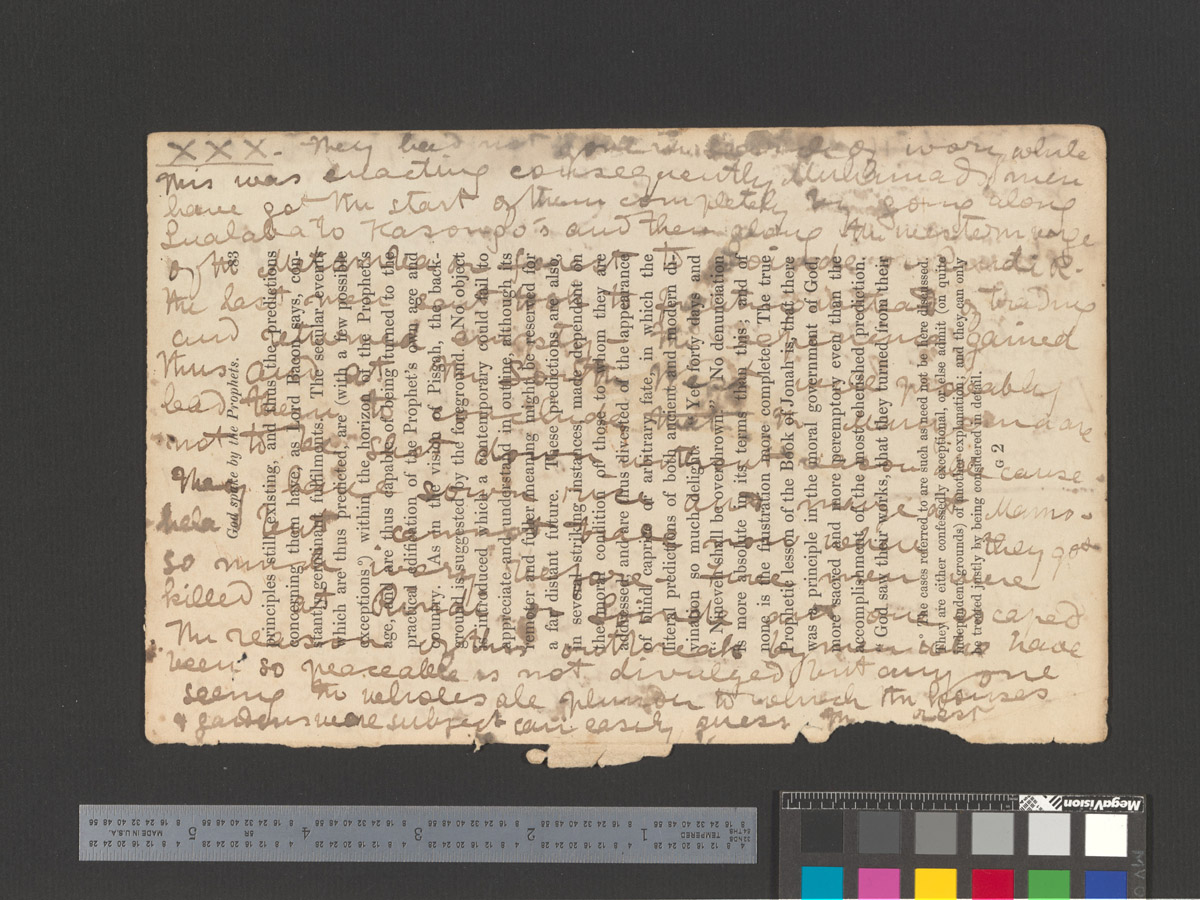

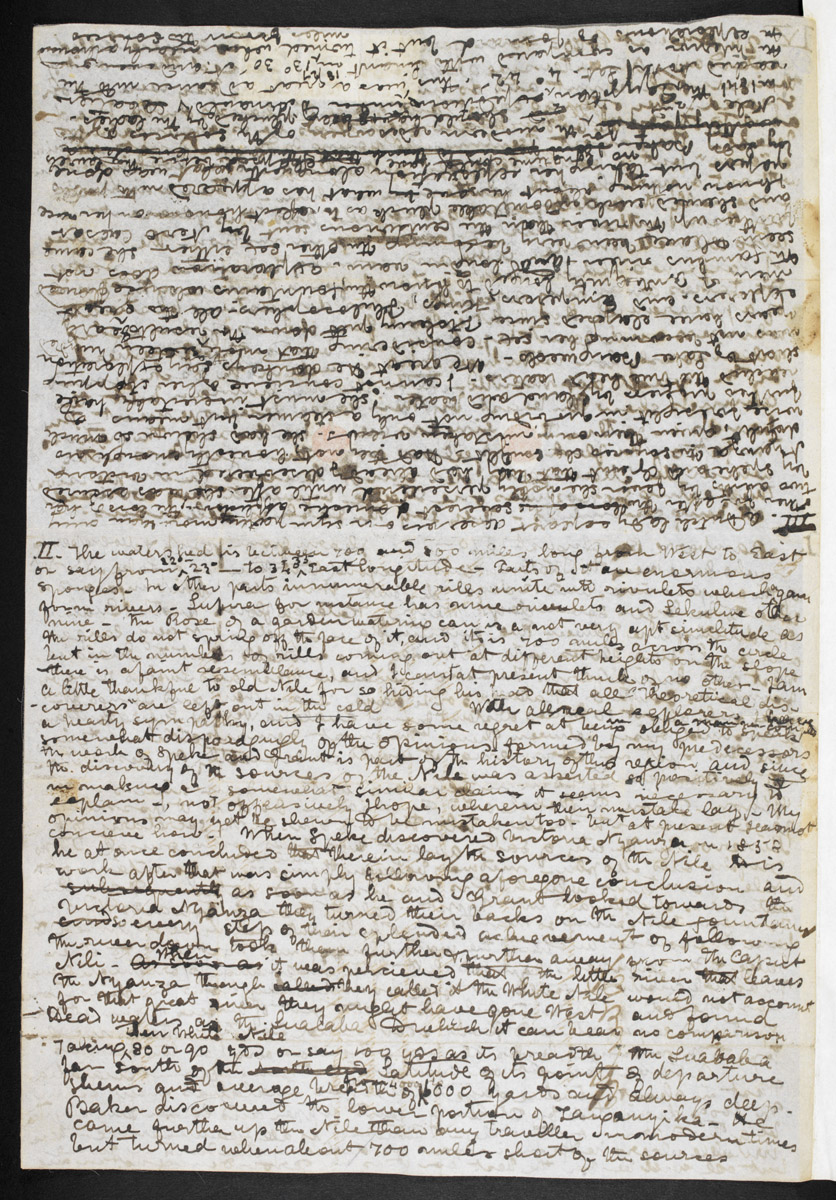

An image of a page of the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870i:XXX). Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. A page of the second gathering that is no longer bound.

The second gathering consists of 41 leaves, which contain 96 pages. The relationship of pages to leaves is not easily summarized. The 37 leaves from Stanley’s book (Livingstone 1870e/1870f/1870i/1870j/1870k) or Birdwood’s article (Livingstone 1871a/1871b) each contain a page on the recto and verso for a total of 74 pages. The leaf of the letter from Gorbello[?] (Livingstone 1871c) contains two pages on the verso and two on the recto, for a total of four pages. The leaf of Baker’s map (Livingstone 1870h) contains four pages on the recto and a single set of calculations on the verso for a total of four pages plus the verso (the latter of which is here treated here as a single page: 1870h:[map]). Finally, one leaf from the Pall Mall Budget (Livingstone 1871e) contains three pages on the recto, four on the verso; the other contains four on the recto, three on the verso, thus totaling 14 pages.

Arrangement of the Second Gathering Top ⤴

The leaves of the second gathering, unlike those of the first, are today disassembled and distributed over three repositories (see Sequencing by Archival Numbers). There are also at least two gaps in the sequence of Livingstone’s numbered pages (pages V-IX and XV-XVI). As a result, we cannot describe with certainty how Livingstone kept the leaves of the second gathering together, although it is reasonable to suppose that he stored them in an ordered stack. The evidence of the leaves, in turn, shows that this stack would have consisted of at least five distinct sub-gatherings, each arranged in a different way.

▲ First sub-gathering (Livingstone 1870c). 1870c forms a single sub-gathering. Livingstone has laid the four pages (I-IV) out two per side on the single leaf of the Gorbello[?] letter. The arrangement of these pages and their orientation relative to one another indicates that Livingstone originally folded this leaf between pages I and IV, so that these pages appeared on the outside – page I right-side up relative to the fold, page IV upside-down. On the inside, pages II and III appeared right-side up relative to the fold and so upside-down relative to one another.

| Two images, each of two pages of the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870c:IV, I, III, II). Images copyright British Library Board, Shelfmark Add. MS. 50184, 169r and 169v. Used by permission. These four pages (which appear on the recto and verso of a single leaf) constitute the whole of the first sub-gathering of the 1870 Field Diary. |

The intended reader would have then read the first page, opened at the fold, rotated 180 degrees, read the second page, rotated 180 degrees, read the third page, closed at the fold, rotated 180 degrees, and, finally, read the last page. (Note: Livingstone himself may have instituted this fold into the source text or, more likely, it was a part of the original letter that Livingstone reused when creating this part of the diary – see Original folds.)

▲ Second sub-gathering (Livingstone 1870e, 1870f). 1870e and 1870f together appear on three loose leaves from the Stanley book with a page each on the recto and verso. Livingstone has oriented each page in the same direction, recto and verso. Livingstone’s numbered pages relative to the pages of the undertext run as follows:

| Livingstone's Number | Undertext Number |

| X | 48 |

| XI | 47 |

| XII | 23 |

| XIII | 24 |

| XIV [v.1] | 21 |

| [XIV v.2] | 22 |

The undertext pages thus do not run in sequence, and there is a gap between the first undertext leaf and the next two. These features suggest that Livingstone first tore these leaves out of the book, then wrote his diary entries only after flipping over vertically (thus not reorienting) the leaves with pages 23/24 and 21/22 of the undertext.

▲ Third sub-gathering (Livingstone 1870h). The majority of text for this sub-gathering appears on the recto of a single leaf, which has Baker’s map of Albert N’yanza (and no Livingstone writing other than one minor calculation) on the verso. Livingstone has divided the recto of this leaf into quadrants (apparently following the original folds of the map – see Original folds), then placed a page in each quadrant. As laid out clockwise from the top left-hand quadrant, the pages are arranged as follows: XX, XVII, XVIII (upside-down), XIX (upside-down). Baker’s map, on the verso, is oriented the same way as pages XX and XVII.

-article-1200.jpg)

An image of four pages of the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870h:XX, XVII, XVIII, XIX IC3). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The image dramatically reveals the underlying folds in this leaf. Livingstone used these folds as guides for laying out the four pages of the diary that appear on this side of the leaf in natural light.

When the recto of this leaf is folded in the middle along the horizontal axis and the horizontal fold is then placed at the bottom, all of the pages will be right-side up. If the leaf is again folded in the middle, but now along the vertical axis so that pages XVII and XX are on the outside, a small booklet is formed, with Livingstone’s pages arranged in the following sequence: XVII (outside, vertical fold to left), XVIII (inside, left side), XIX (inside, right side), XX (outside, vertical fold to right). This arrangement also folds the unmarked map into the hidden interior of the booklet (thereby rendering it invisible to the reader), a point that helps account for why Livingstone did not write any diary entries over the map.

▲ Fourth sub-gathering (Livingstone 1870i, 1870j, 1870k, 1871a, 1871b). Within this sub-gathering, Livingstone’s pages appear in an unbroken sequence, while the undertext leaves/pages run almost continuously, albeit in reverse order relative to Livingstone’s pages. All told, there are three main undertext sequences: 1) Stanley’s book, pages 92-69, 66-63, 60-53 (Livingstone 1870i:XXI-LV), 2) Stanley’s book, pages 114-95 (Livingstone 1870i:LVI-LXI, 1870j:LXII-LXIX, 1870k:LXX-LXXV), and 3) Birdwood’s article, pages 12-1 (Livingstone 1871a:LXXVI [v.1]-[LXXVI v.2], 1871b:LXXVIII-LXXXVII).

With one exception the pages of this sub-gathering are loose, and its arrangement is fairly easy to ascertain. On each leaf, Livingstone writes on the recto, then flips the leaf horizontally and writes on the verso. As a result, the sub-gathering functions like an unbound booklet where, as each successive leaf is flipped up, the pages of the resulting two-page opening are both oriented right-side up, one above the other. Assorted page-to-page smearing of Livingstone’s text supports the case for this arrangement of Livingstone’s diary leaves, as do more pronounced saturation patterns on pages XXV-LV and, separately, LVI-LXI (see The big stain).

![Animation of a sequence of pages from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870i:XXXIX-LV [v.2] flipbook). Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). Animation of a sequence of pages from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870i:XXXIX-LV [v.2] flipbook). Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/creating-the-1870-field-diary/liv_000205_0019-0036_flipbook_0.5-small.gif)

Animation of a sequence of pages from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870i:XXXIX-LV [v.2] flipbook). Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. Two pages are shown on each side, the recto image of a page together with the verso image of the previous page as if the pages were open on the table and being flipped one page at a time. On the left are natural light images; on the right are corresponding spectral images processed to enhance topography.

Additional damage to the leaves in this sub-gathering is also consistent with the arrangement. Indeed, in combination with topographical spectral images, the arrangement reveals two important patterns of damage. In the first case it is clear that some sort of sharp object has punctured successive leaves of the diary (LV [v.2] downward to at least XXXV) and that this occurred after Livingstone had written his text and arranged the leaves, as the puncture obscures Livingstone’s writing on multiple pages.

In the second case, the appropriate arrangement of leaves shows the presence of a small hole in one corner, again across multiple leaves (pages XXI-LV). This hole, like the puncture, was made after Livingstone wrote, as the hole also removes parts of the diary text. However, given its corner placement, this hole may be where Livingstone tied this set of pages together, as he did with the booklet made up of Quarterly Review margins (Livingstone 1870b). In fact, on the earlier pages in the sequence, the hole more resembles a tear running all the way to the edge of the page (see especially pages XXI-XXVI), as would happen with a thread working through the pages as they were lifted and lowered repeatedly (for more on the damage, see Manuscript holes).

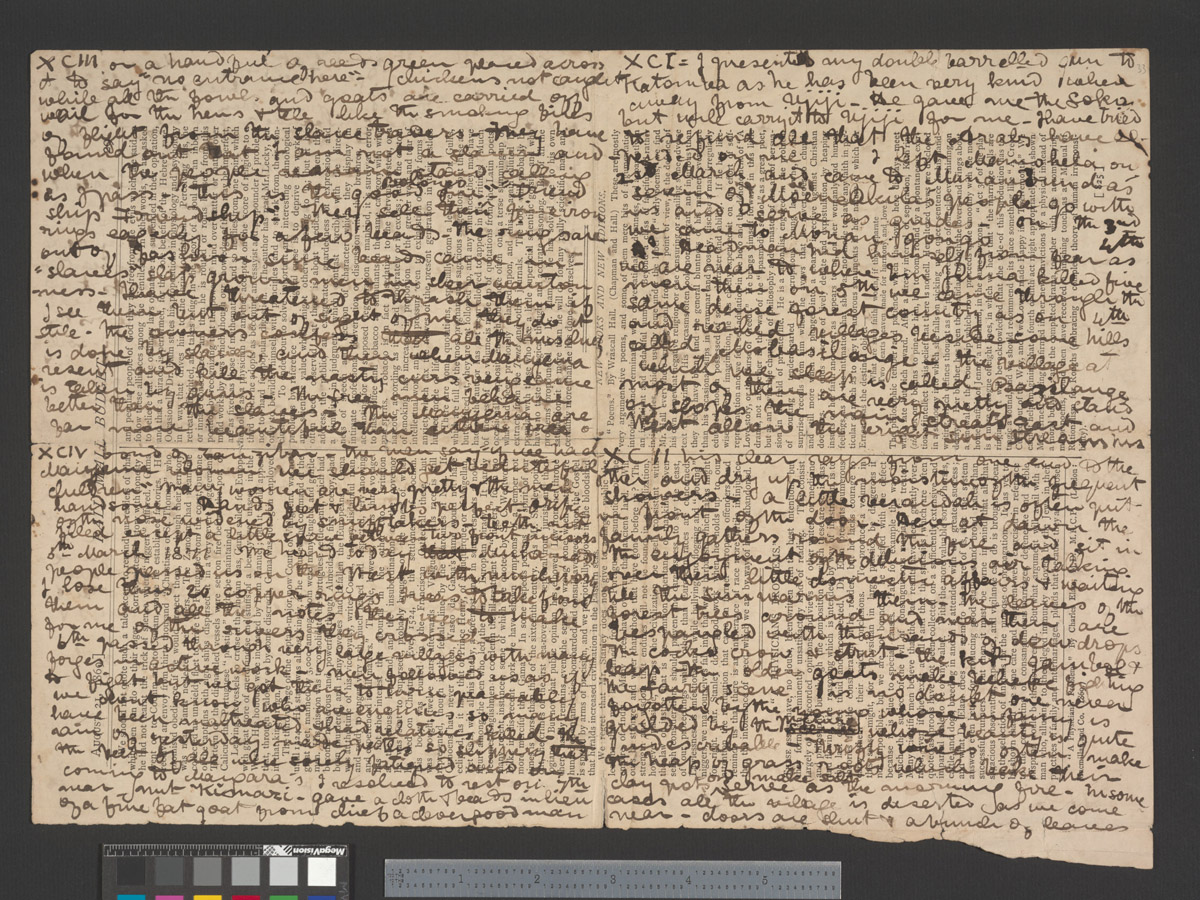

An image of two bound pages of the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870k:LXV, LXVI). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The original binding string is visible on the right side between these two images.

The one (partial) exception to the proposed arrangement of this sub-gathering spans pages LXII-LXIX. Here the original leaves of Stanley’s book remain bound together two and two, indicating that Livingstone removed these pages from the book rather than tear them out one by one. As a result, it appears that in arranging these leaves, Livingstone first folded each pairing, then placed the second inside of the first (or that he simply kept the arrangement as originally set in Stanley’s book – binding string from Stanley’s book is visible in our images). The result is that these four leaves – in contrast to the other leaves in this sub-gathering which appear to have been stacked on top of one another – form a small, semi-bound booklet.

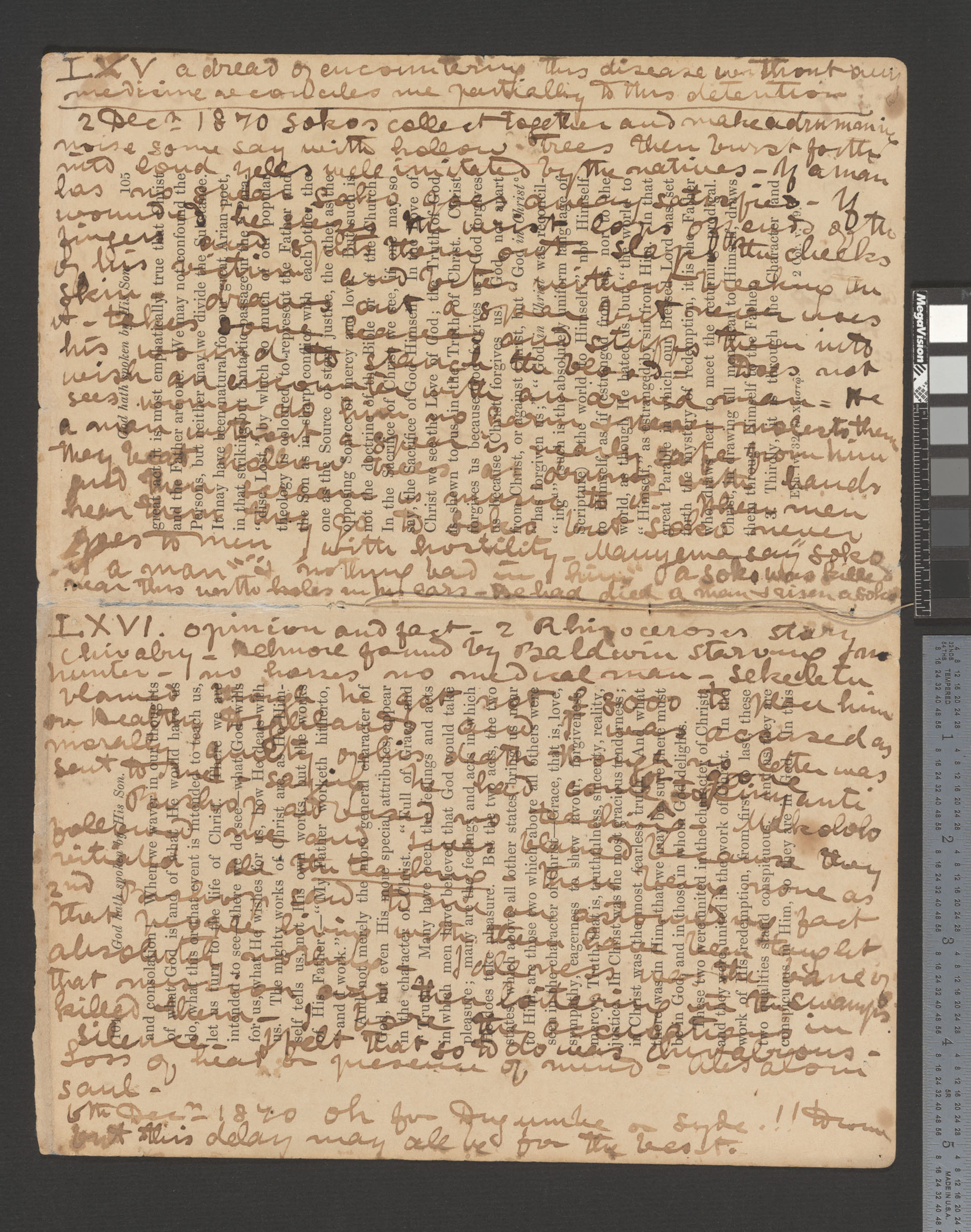

▲ Fifth sub-gathering (1871e). Livingstone was beginning to run low on any kind of writing paper when he began to compose the pages that constitute the fifth and final sub-gathering of the 1870 Field Diary. As a result, he shifted from the sturdier book pages of the previous sub-gatherings to more fragile newspaper pages for this sub-gathering and, subsequently, for the bulk of the 1871 Field Diary. Pages LXXXVIII-CI thus appear on the recto and verso of two leaves of the Pall Mall Budget.

By comparison to the preceding leaves of Stanley’s book (215mm x 140mm) and Birdwood’s article (215mm x 140mm), the Pall Mall Budget leaves are significantly larger (385mm x 270mm), thereby enabling Livingstone to divide each side of each newspaper leaf into four quadrants. One diary page appears per quadrant, except for pages XC and CI, which each span two quadrants from top to bottom. The resulting layout of pages across the two leaves, then, is slightly irregular.

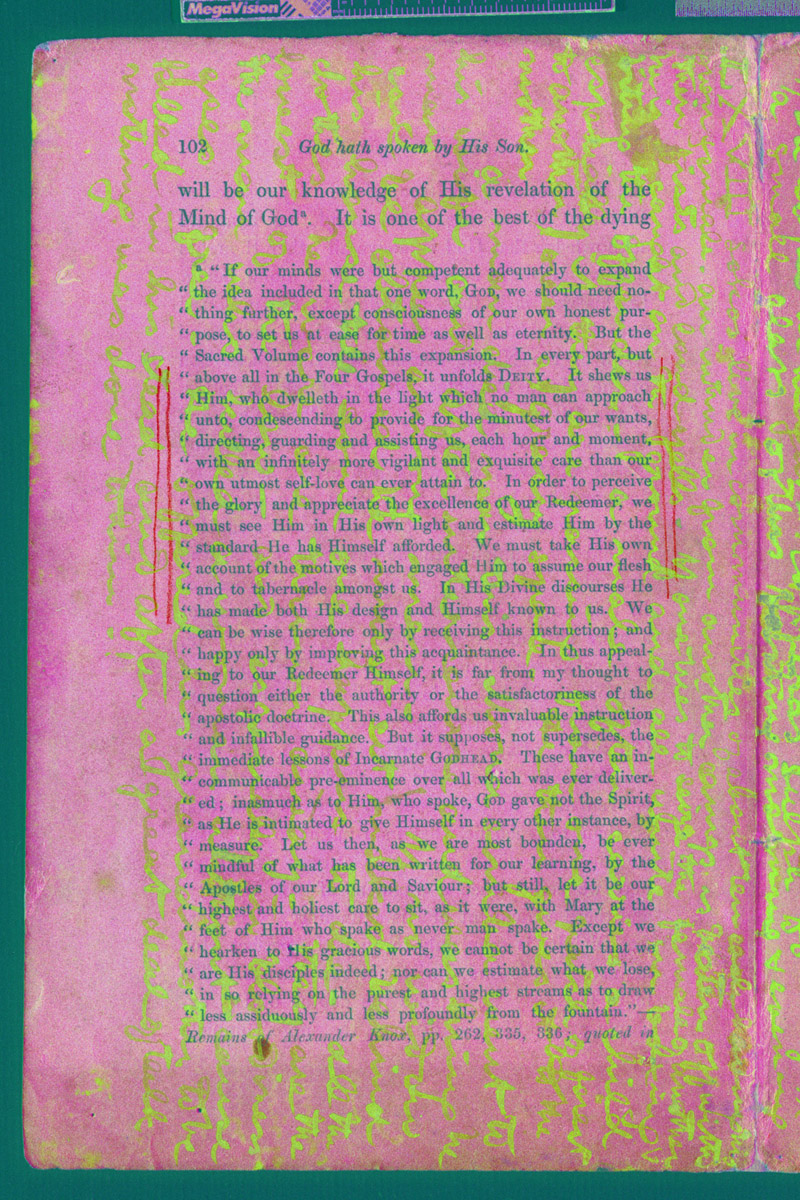

A processed spectral image of three pages of the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871e:XCIX, C, CI color_raking). Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The image shows the close relationship between the principal horizontal and vertical folds in the leaf and the layout of Livingstone's pages in relation to these folds.

The evidence of our topographical spectral images, especially when set against the evidence of the textual layout, indicates that Livingstone folded each leaf twice when arranging this sub-gathering (or that he reused existing folds in this source text – see Original folds). First, he folded along the vertical axis with the left side folding below the right side, then a second time along the horizontal axis with the bottom folding below the top. This resulted in diary pages (192.5mm x 135mm) of roughly the size of the preceding book and article pages.

Thanks to this folding, four of the pages (the lower-numbered ones on the given leaf) went to the outside and the intended reader could read this sub-gathering as follows:

1) Read the lowest-numbered page (LXXXVIII or XCV, respectively);

2) Flip once along the horizontal axis to read the next page (LXXXIX or XCVI);

3) Flip along the horizontal axis again, but now open the horizontal fold and read the two visible pages top to bottom (XC first part to XC second part, or XCVII to XCVIII).

With this point reached, the reader could now turn to the interior pages. To access these pages, however, required more folding:

4) Unfold along the vertical access to show the full leaf, then refold along the vertical axis so that the left page now goes over the right;

5) Fold along the horizontal axis so that the top goes over the bottom;

6) Flip along the horizontal axis (first Pall Mall Budget leaf) or rotate 180 degrees (second Pall Mall Budget leaf).

Finally, from here, the sequence of reading restarted with step #1 above.

Page Layout and Orientation Top ⤴

The first gathering of the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870b) consists of clippings derived from the top, bottom, gutter, and outside margins of a review article from the Quarterly Review. In this gathering Livingstone writes on the successive rectos and versos of all the leaves. Livingstone’s text relative to the printed text (which is not always visible on the given clipping) may be parallel, perpendicular, or upside-down.

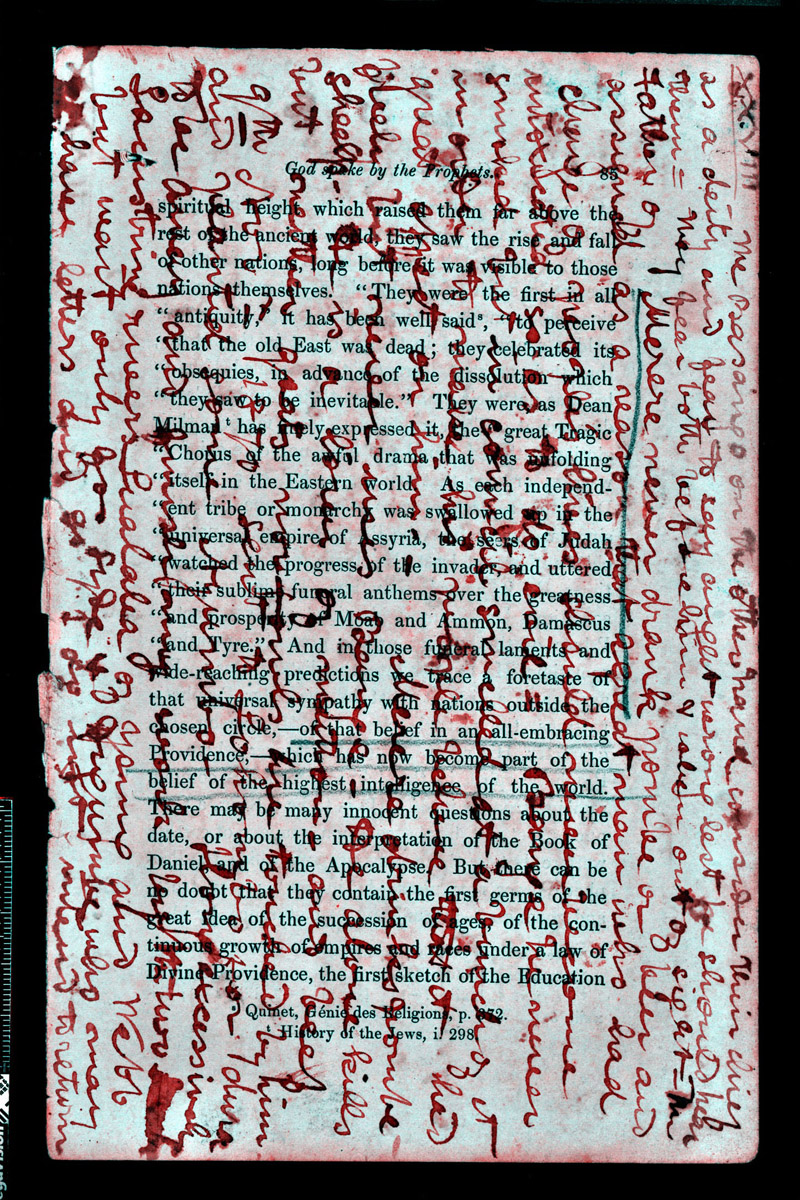

In the second gathering, Livingstone writes across full pages (rather than marginal clippings) and most often composes one numbered diary page per side of leaf. Usually, such numbered pages appear on both the recto and the verso of the given leaf. Livingstone also tends to write his entries perpendicular to the underlying pre-printed, so that the printed text appears 90 degrees clockwise relative to Livingstone’s text.

An image of four pages of the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871e:XCIII, XCIV, XCI, XCII). Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. This the only set of pages written over a leaf from the Pall Mall Budget where all of Livingstone's pages have the same orientation.

There are a few exceptions to the above rules, however. In terms of layout exceptions, Livingstone places the first four numbered pages (1870b:I-IV), two per side (I and IV, and II and III, respectively), over the recto and verso of the letter from Gorbello[?]. He also composes either three or four pages on each side of each leaf when writing over the two leaves from the Pall Mall Budget (Livingstone 1871e). In two of the Pall Mall Budget cases, he divides the side of a leaf into quadrants, resulting in four pages per side of leaf. In the other two cases, he divides the side of the leaf into halves, then subdivides only one of the halves, meaning that one diary page covers half of the leaf, while the other two each cover a quadrant, resulting in three pages per side of leaf.

In terms of orientation exceptions, Livingstone writes parallel to printed text on Baker’s map (Livingstone 1870h:[map]) and to the printed text on 1871a:[LXXVI v.2]. He also writes parallel to handwritten undertext on 1870c:IV and 1870h:XVII. The pages on the leaves of the Pall Mall Budget (Livingstone 1871e) are usually oriented in two directions, so that on any given leaf side half the pages are upside-down relative to the other half. As a result, on these leaves the printed undertext may be 90 degrees clockwise or counter-clockwise relative to Livingstone’s text. 1871e:XCI, XCII, XCIII, and XCIV, which occupy one side of one Pall Mall Budget leaf, however, all have the same orientation. As a result, the printed undertext on this side of this leaf runs 90 degrees counter-clockwise relative to that of all of Livingstone’s numbered pages.

![A processed spectral image of a page of the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871a:[LXXVI v.2] PCA_pseudo_32). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). A processed spectral image of a page of the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871a:[LXXVI v.2] PCA_pseudo_32). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/creating-the-1870-field-diary/liv_000203_0002_PCA_pseudo_(liv_000205_0032_stats)-article.jpg)

A processed spectral image of a page of the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871a:[LXXVI v.2] PCA_pseudo_32). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. Livingstone's writing on this page covers three of the four cardinal directions.

Finally, 1870f:[XIV v.2] and 1871a:LXXVI [v.1] present unusual cases in terms of page orientation. On 1870f:[XIV v.2], the orientation of the map and its related annotations covers three of the four cardinal directions. In the case of 1871a:LXXVI [v.1], although there is no printed or handwritten undertext, a series of calculations run 90 degrees clockwise to the main diary text and would have been parallel to the print text were there any (see Additional notes on the undertexts for more on the calculations; 1870i:LII also has one underlying calculation [in Livingstone’s hand] that runs parallel to the main diary text.)

Initial Stages of Creation Top ⤴

The above analysis indicates that Livingstone developed the manuscript of the 1870 Field Diary in stages, over time. In addition, it is clear that Livingstone also engaged the diary’s source texts in a number of ways prior to using them to composed the main text of the diary. Definitive dating of the initial interactions appears impossible either based on internal evidence or by corroboration from other Livingstone documents. Nonetheless, some general points based on reasonable inference may be made about the nature and sequence of these interactions. These points help account for the placement of text and other markings on various parts of the diary.

▲ Acquisition of the undertexts. Livingstone wrote the 1870 Field Diary over a heterogeneous series of printed and handwritten documents, as previously noted (see Livingstone's Undertexts). The dates of these original documents (1863, 1866, 1869) indicate that he probably took some of the documents with him on his final journey (1866-73), while others arrived en route.

![An image of a page of the 10 March 1870 'Retrospect' (Livingstone 1870a:[7]), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of the 10 March 1870 'Retrospect' (Livingstone 1870a:[7]), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/creating-the-1870-field-diary/liv_000211_0004_color-article.jpg)

An image of a page of the 10 March 1870 'Retrospect' (Livingstone 1870a:[7]), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. In this segment, Livingstone directly refers to the anonymous review of books on Irish Chursh History from the Quarterly Review that he uses as the source text for the first gathering of the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870b).

From the Letter from Bambarre (Livingstone 1871c), for instance, we know that Horace Waller sent Livingstone the copy of The Standard (24 November 1869) upon which the latter eventually wrote the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871f). The near contemporaneous dating of the Pall Mall Budget leaves of 21 August 1869 (Livingstone 1871e) suggests that Livingstone received this document from Waller as well. Additionally, the 10 March 1870 “Retrospect” references the Quarterly Review essay (see Livingstone 1870a:[7]) so Livingstone clearly had the essay by that date.

▲ Annotation of one undertext. As a first step to using the undertext documents, Livingstone appears to have annotated at least one of them. Multiple pages from Stanley’s The Bible: Its Form and Substance bear marginal annotations in the form of a straight penciled line alongside several lines from the printed text.

| (Left; top in mobile) An image of a page of the 1870 Field Diary that combines two separate processed spectral renderings (Livingstone 1870ij:LXVIII ICA_pseudo_1 and PCA_pseudo_34). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. (Right; bottom) A processed spectral image of a page of the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870i:XXVIII pseudo_v1). Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. These two pages demonstrate, respectively, Livingstone's use of a red pencil (rendered red in the spectral image) to make marginal annotations on his source text, and his use of a gray pencil (rendered in dark gray/black) to make marginal annotations and to underline a set of textual lines. |

On a significant portion of pages the annotations are in gray pencil (1870i:XXI, XXIV-XXVIII, XXXIII-XXXV, XXXVII, XLVI, XLVIII, L, LI, LIV, LV [v.1], LV [v.2]); a few pages have annotations in red pencil (1870i:LXI; 1870j:LXVI, LXVIII; 1870k:LXX). 1870i:XXVIII also has several lines of printed text underlined. The general thematic unity of the annotated passages provides insights into Livingstone’s interests as a reader of this text.

Bonus: Download a transcription of all the passages annotated by Livingstone from Stanley’s The Bible: Its Form and Substance.

▲ Additional notes on the undertexts. Concurrently with marginal annotations or, at least, in advance of writing the main text of the 1870 Field Diary, Livingstone also appears to have made notes on a few of the source texts. For instance, 1871a:LXXVI [v.1] includes a series of calculations (more than any other page in the diary) made in pencil and in a number of different inks. Some of these calculations clearly run under the main diary text. (For another example of an underlying calculation, see 1870i:LII.) Indeed, the diary text on 1871a:LXXVI [v.1] uncharacteristically stops before the bottom of the page – just before the part of the page where the majority of calculations lie.

Based on these characteristics, it seems probable that Livingstone used this page first for calculations at different times, then reused it when he composed the main diary text. The fact that this page is the back of the last page of Birdwood’s article from the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bombay also makes the page a likely place for such ad hoc calculations.

| A natural light image (left; top in mobile) and a processed spectral image (right; bottom) of a page of the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870k:[LXXVI v.2] color, IC3). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. In contrast to the majority of pages in the 1870 Field Diary, Livingstone has here composed his text parallel to the printed text (on the other side of this leaf). Additionally, the spectral image shows that Livingstone has written the text with two different kinds of inks, one of which disappears in the processed image version. |

Similarly, 1871a:[LXXVI v.2] bears a map (with annotations) whose ink clearly differs from the diary pages that precede and follow this one. The text of this map also, uniquely, runs parallel to the underlying printed text (rather than perpendicular) – a characteristic not present on any other page of the diary excepting those written on the back of Baker’s map (Livingstone 1870h:[map]; see Page Layout and Orientation). These features (and the lack of any diary text on this page) suggest that Livingstone drew this map in advance of drafting the main diary text.

At least one other map also appears to pre-date the composition of the main text. This map appears at the bottom of 1870h:XVII. Analysis of our spectral images suggests that this map is of a different ink from the text on the rest of the page. Indeed the text on this page generally goes around the map, although a few parts of the map clearly lie underneath the page’s main text. As a result, it again seems likely that Livingstone drafted this map prior to writing the main diary text on this page. (For more on the maps on 1870h:XVII and 1871a:[LXXVI v.2] see Pre-composition.)

A processed spectral image of a page of the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871b:LXXXVII), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. Beneath Livingstone's main text in this image (in black) appear two additional lines (in blue): “Mr andso [sic] twill be / when I am gone.”

Finally, 1871b:LXXXVII has two short lines of text in Livingstone’s hand that run parallel to the main text but appear beneath it. These lines read: “Mr [A]ndso twill be when I am gone.” The identity of the individual named is not known, and the meaning of these lines is also otherwise unclear.

*

The state of the 1870 Field Diary, therefore, reflects a complex series of decisions that Livingstone made in assembling and arranging the text. By foregrounding those decisions by reading the pieces of this scattered text in an integrated fashion, we can partially recover the conditions under which Livingstone wrote and traveled, and and we can outline his frameworks for recording information. The next part of this essay explores additional structures imposed on the manuscript over time and discusses other prominent textual features.

![Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_013723_0001-new-carousel_0.jpg)

![Processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's "Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal" (Livingstone 1870a:[3] pseudo_v4_BY), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's "Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal" (Livingstone 1870a:[3] pseudo_v4_BY), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000211_0003_pseudoBY_940_by_592-carousel.jpg)

![David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, [1869], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland: CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, [1869], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland: CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_003006_0001-new-carousel_0.jpg)

![An image of a page of the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870k:[LXXVI v.2]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870k:[LXXVI v.2]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/creating-the-1870-field-diary/liv_000208_0002_color-article.jpg)

![A processed spectral image of a page of the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870k:[LXXVI v.2] IC3). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). A processed spectral image of a page of the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870k:[LXXVI v.2] IC3). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/creating-the-1870-field-diary/liv_000208_0002_IC3_(liv_000204_0001_trans)-article.jpg)