Livingstone's Composition Practices

Cite page (MLA): Ward, Megan, and Adrian S. Wisnicki. "Livingstone's Composition Practices." In Livingstone's 1870 Field Diary. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. University of Maryland Libraries, 2017. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/ec4831b5-1dfb-407f-9029-5c6e5715933c.

This essay explores Livingstone’s composition practices from 1870-1871 in order to show how they vary from the practices scholars have previously identified in Livingstone’s other works. As such, the manuscripts from this period – Field Diary XIII, the 1870 Field Diary, and the Unyanyembe Journal – offer insights into how the circumstances of imperial exploration change composition practices. The essay also discusses the material edited out from Livingstone’s posthumously published Last Journals (1874).

Introduction Top⤴

During the second half of 1870, David Livingstone was at a particularly low point. His mission to find the source of the Nile had become an “obsession,” in the words of his biographer Tim Jeal, “a compensation for every other failure” (Jeal 2013:367). Yet, despite his sense of urgency, Livingstone was stranded in Bambarre, a village in central Africa, and was unable to travel due to illness and flesh-eating ulcers on his feet.

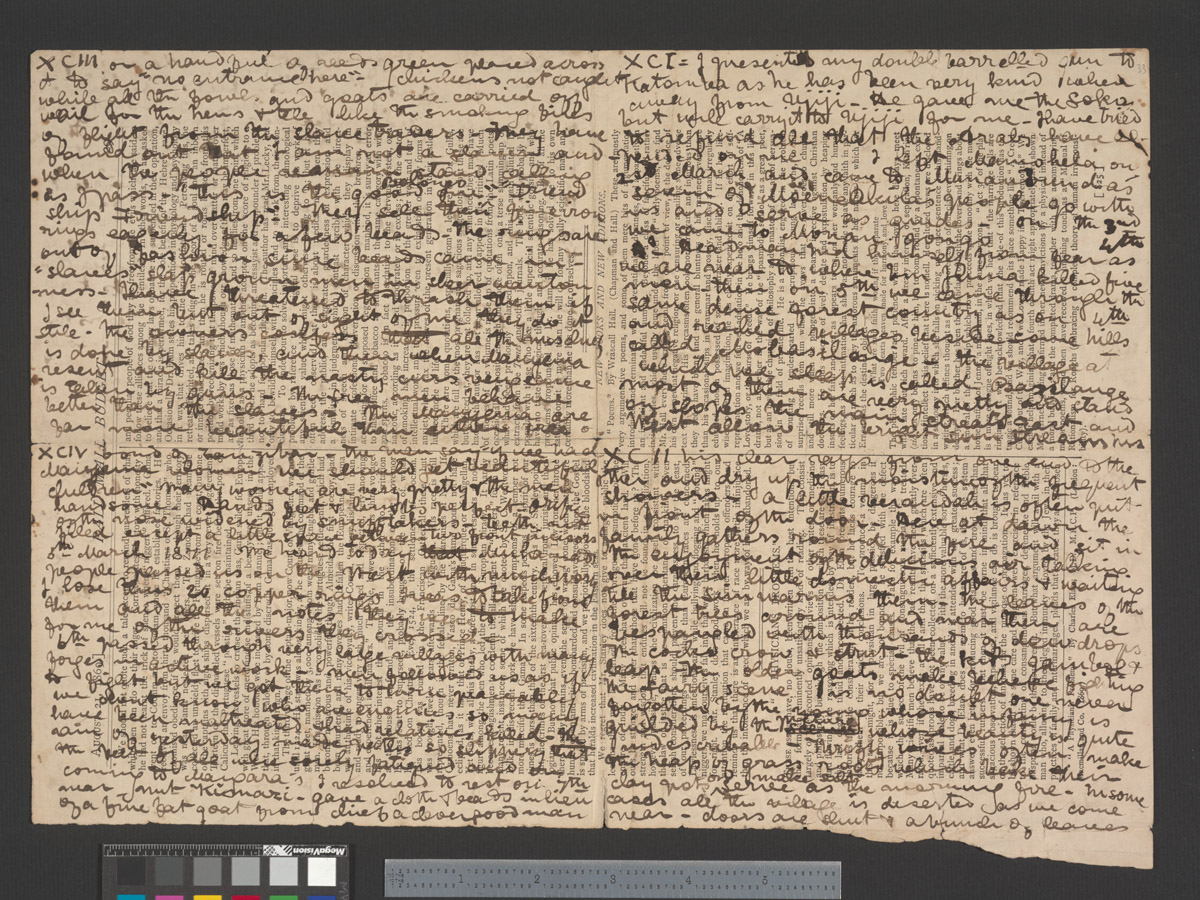

A page of the 1870 Field Diary written over a newspaper page (Livingstone 1870e:XCI, XCII, XCIII, XCIV). Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported.

Depressed and isolated, Livingstone spent much of this time waiting for a box to arrive from Ujiji that contained medicine, food, letters from Europe, and – crucially – paper on which to record his observations. The manuscripts in which he recorded his thoughts during this time offer a unique perspective both on Livingstone’s own self-presentation and on the historical frameworks scholars have used to interpret Livingstone’s composition practices.

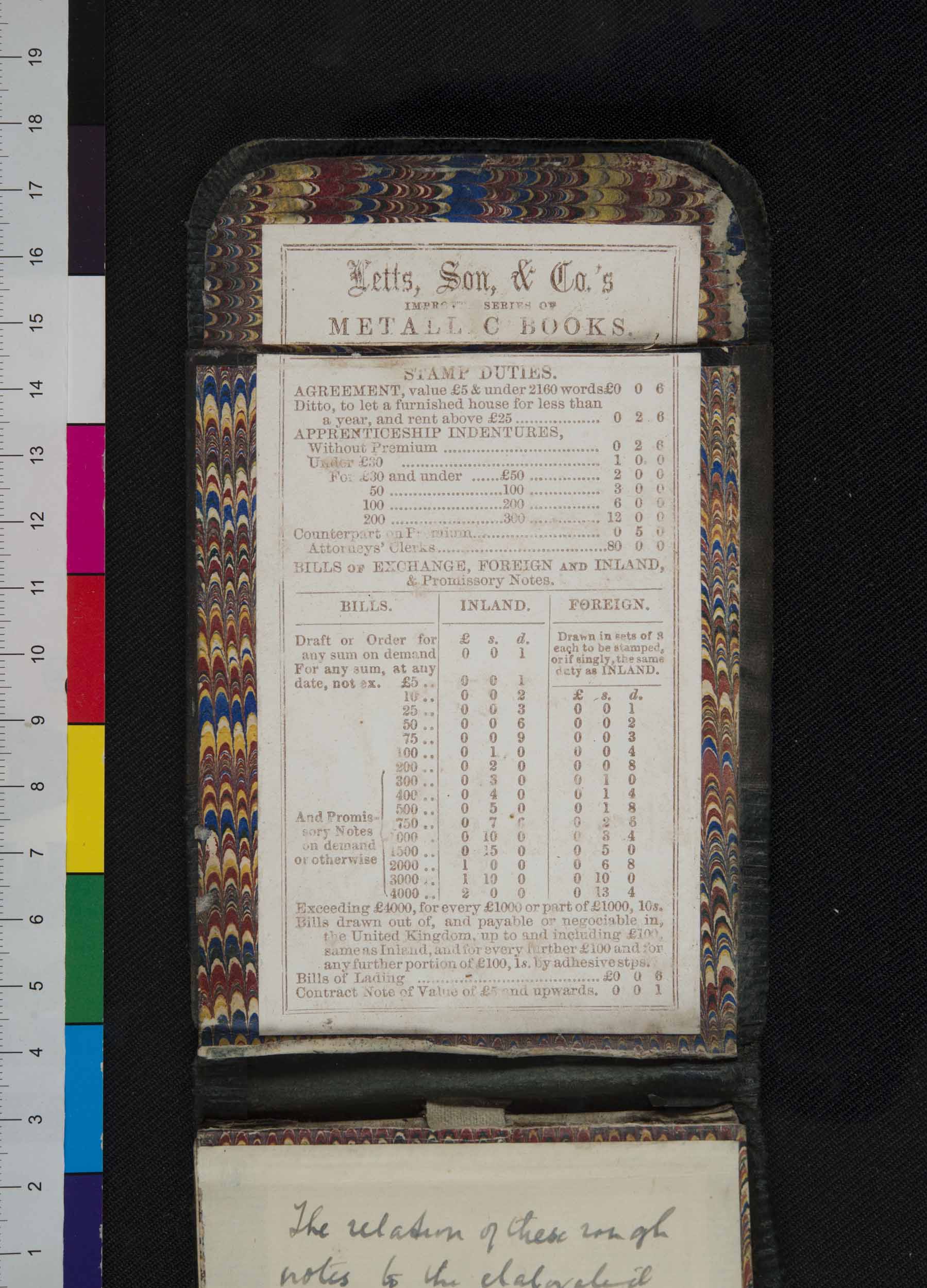

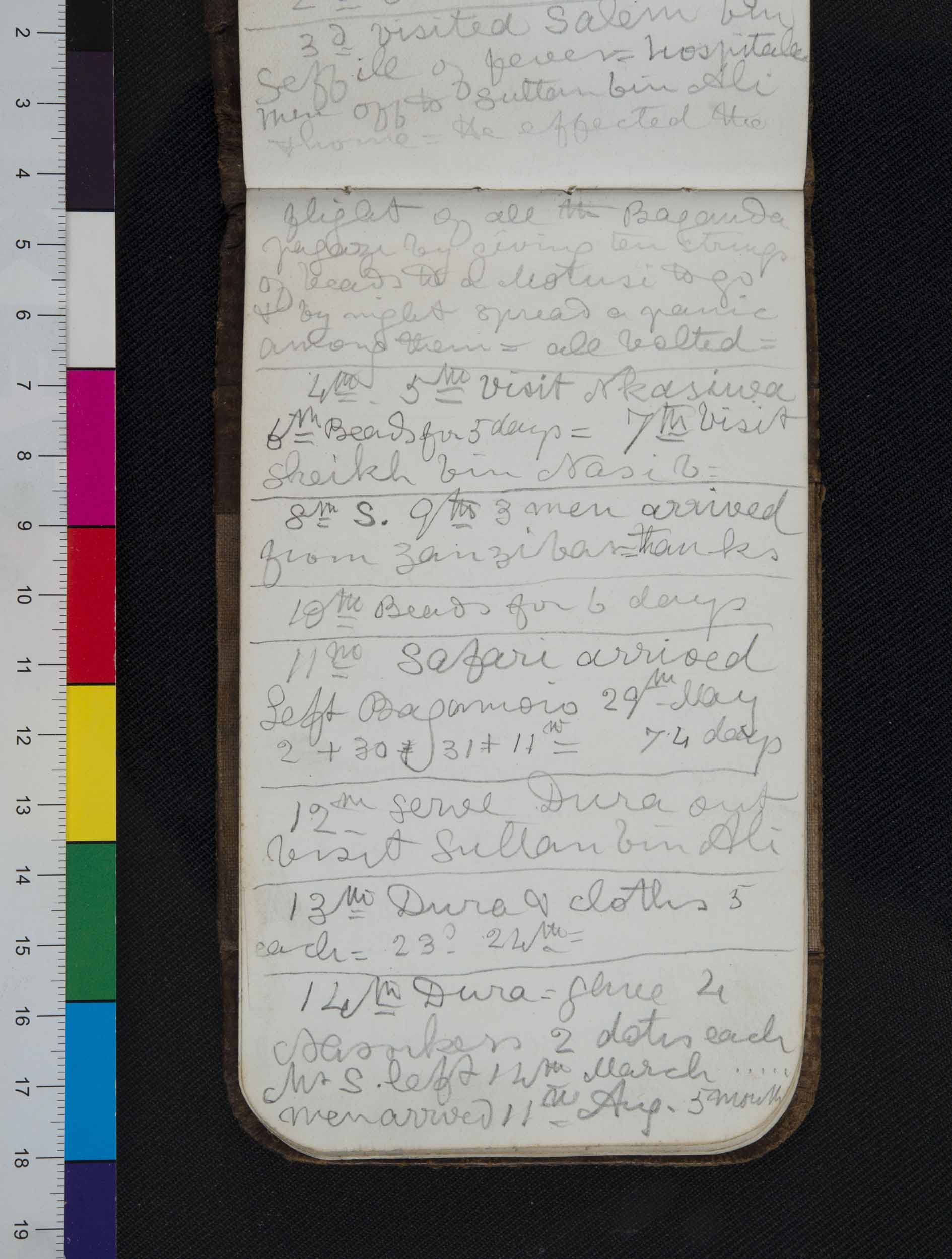

Until the box arrived, Livingstone kept two primary records. The first, Field Diary XIII (28 June 1869-25 Feb. 1871), was the last of a supply of small stenographer-style notebooks Livingstone had been filling up since 1866. Small, with the spine at the top, this notebook was primarily used to scrawl shorter notes, often in pencil. The second, the 1870 Field Diary (17 Aug. 1870-22 Mar. 1870), was constructed from other printed materials Livingstone had on hand and made in stages, perhaps because Livingstone held out hope of receiving more paper.

![Samuel White Baker's map of the Albert N'yanza (Lake Albert), over which Livingstone wrote a segment of the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870h:[map]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). Samuel White Baker's map of the Albert N'yanza (Lake Albert), over which Livingstone wrote a segment of the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870h:[map]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/livingstones-composition-practices/liv_000204_0002_color-article-1200.jpg)

Samuel White Baker's map of the Albert N'yanza (Lake Albert), over which Livingstone wrote a segment of the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870h:[map]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. Livingstone covered the back of the map with text, but left the map itself unmarked except for a small segment with calculations in the lower left-hand corner. The segment also includes an addition (upside-down) in another hand.

To create the 1870 Field Diary, Livingstone first cut off the margins a periodical article and fastened these together to create a little booklet of 35 leaves. Then, with no paper forthcoming, he wrote over an old letter, three leaves from a printed book, and one or more texts that have not survived. He then turned to a large map as his source of paper. Finally, he tore out 34 leaves from a variety of publications and wrote crosswise over the printed text. In February 1871, Livingstone finally received supplies from the coast, including food and some new publications. The 1870 Field Diary thus concludes with some pages written over the Pall Mall Budget, while the 1871 Field Diary continues on a copy of The Standard.

It was not until much later that Livingstone once more gained access to his third record, one that gives us our final account of this period. The Unyanyembe Journal (28 Jan. 1866-5 Mar. 1872), a large volume with ruled pages and bound in leather, was stored in the village of Ujiji. When Livingstone returned to Ujiji (as he did in the fall of 1871), he copied over entries from the first two records, Field Diary XIII and the 1870 Field Diary, into the Unyanyembe Journal.

| Name | Material | Start and End Dates | Relevant Entries |

| Field Diary XIII | small stenographer notebook | 28 June 1869-25 Feb. 1871 | 17 Aug. 1870-25 Feb. 1871 |

| 1870 Diary | a letter, a map, pages from books and periodicals | 17 Aug. 1870-22 Mar. 1870 | 17 Aug. 1870-22 Mar. 1870 |

| Unyanyembe Journal | large, leather bound journal with ruled pages | 28 Jan. 1866-5 Mar. 1872 | 23 July 1870-21 Mar. 1871 |

Livingstone’s written records, July 1870 - March 1871. This table does not include letters.

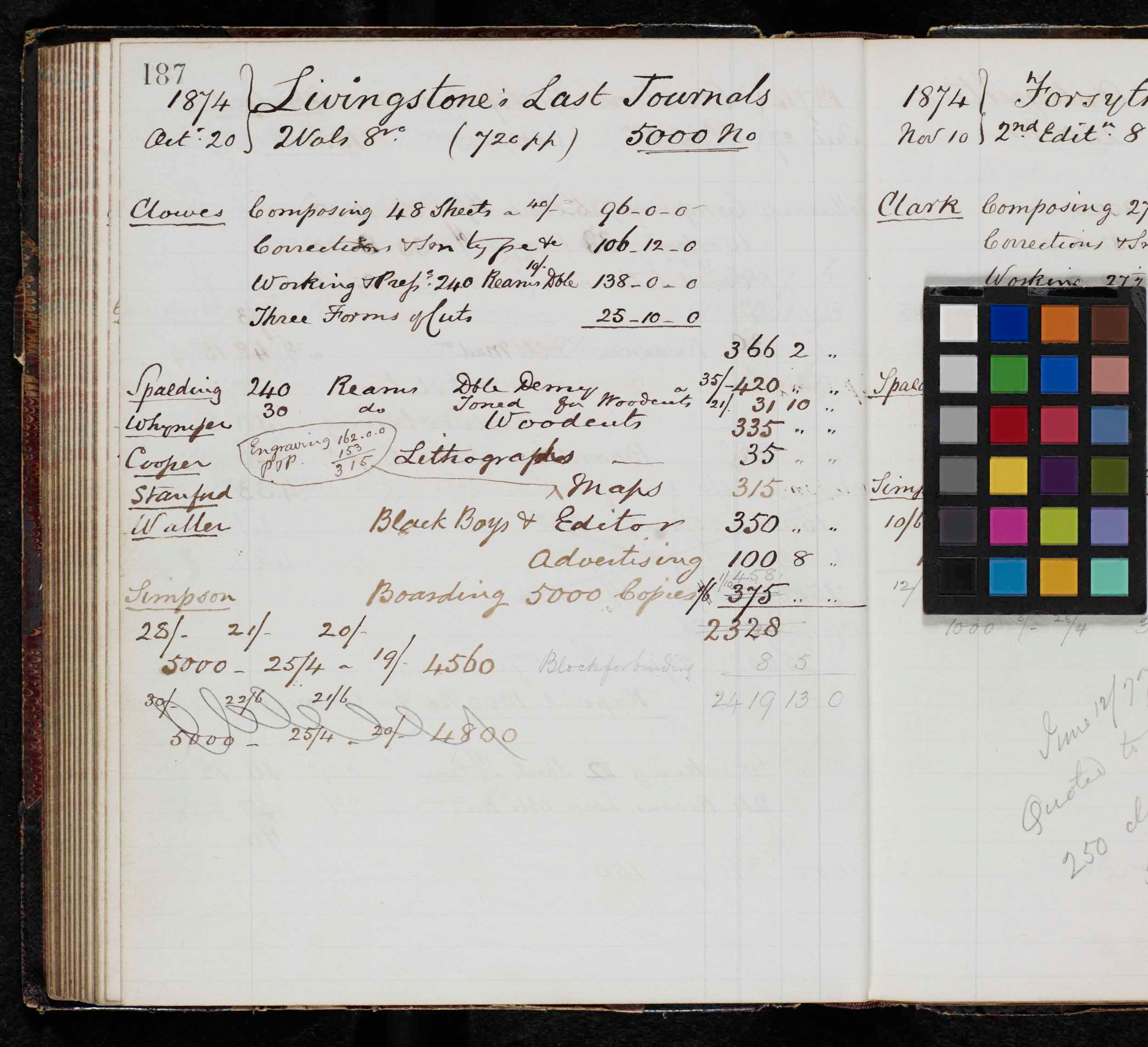

After his death, Livingstone’s final writings were edited by his friend Horace Waller and published in two volumes as the Last Journals (1874). For this period, however, Waller primarily relied on the 1870 Field Diary rather than the Unyanyembe Journal (his default text in preparing the Last Journals). As a result, when we take the 1870 Field Diary, the Unyanyembe Journal, and Field Diary XIII together, we can create a more diverse, patchworked record of the period July 1870 - March 1871, the time when Livingstone was stranded in Bambarre and also the time directly pre-dating his visit to Nyangwe.

Bonus: Download a PDF copy of the original edition (25.1 MB) of Livingstone's Last Journals (1874), volume II. Pages 48-109 of this volume correspond to the 1870 Field Diary.

Double-bonus: Download a PDF copy of a photocopy of the corrected proofs (21 MB) of Livingstone's Last Journals (1874), volume II. This segment of the proofs corresponds to the 1870 Field Diary. The photocopy has been marked with Roman numerals by the present editorial team to correlate the proofs with Livingstone's original manuscript pages.

Stages of Composition Top ⤴

Scholars have typically characterized Livingstone’s composition practices according to a three-stage model. This model, devised by Roy C. Bridges, outlines the process by which the text of Livingstone (and other explorers like him) moved from field observations to published texts. The first stage, according to Bridges, might include “immediate observations recorded day by day in notebooks [ . . . ] often together with sketches, calculations, vocabularies and jottings noting some of / the things that have been preoccupying him” (Bridges 1977:3-4).

The second stage would be a secondary journal, like the Unyanyembe Journal, which “omitted, amended or expanded the material in the notebooks,” as well as letters in which Livingstone often reworked his accounts (Bridges 1977:4). Finally, the third stage included revisions by editors, family, and publishers and ultimately became the basis of the published accounts - popular and scientific - of the given expedition.

| (Left; top in mobile) A page from the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[625]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. (Right; bottom) The corresponding page from the Last Journals (Livingstone 1874,2:102). Courtesy of the Internet Archive |

The earliest writing is, in this framework, the least mediated, or as Bridges terms it, “the ‘raw’ record,” meaning that we should consult this version to get the least filtered account of contact narratives (Bridges 1998:70). Of course, as Bridges’s scare quotes suggest, no record is completely unmediated, but nonetheless, scholars have tended to read each successive stage as a rewriting of the one before. In this reading, as Ian MacLaren describes it, the movement from stage to stage becomes a process of “editing of parallel or variorum editions of narratives” (MacLaren 1992:61).

The final texts, therefore, are not only the result of a professional editor; Livingstone and other explorers self-censored as each stage went by, editing out the descriptive details about daily life and other information from their field diaries. The effect in Livingstone’s case, Dorothy Helly argues, is that, as we move through the manuscript stages, we lose the texture of Livingstone’s daily life, an argument that contributes to our understanding of the field diaries as the most “‘raw,’” as Bridges puts it. Helly concludes, “If we compare those daily field notes with his finished journal, we understand how Livingstone decided to present his activities” (Helly 1987:151).

Exceptions to the Rule Top ⤴

From July to February of 1870, however, we have a period whose records pose an exception to this characterization of the typical explorer writing practices. Because of his limited supplies, Livingstone created a first-stage document (Field Diary XIII) that is largely self-enclosed and not developed further.

The 1870 Field Diary falls somewhere between the first and second stages, as it is often the first record of an event, but it does also sometimes revise and expand upon events jotted down in Field Diary XIII. However, many parts of the 1870 Field Diary never went through a second stage before being published as the Last Journals. The Unyanyembe Journal, usually Livingstone’s second-stage document, was unavailable to Livingstone and therefore bears only a few accounts from this period.

Neither Field Diary XIII nor the 1870 Field Diary, then, fit neatly into the typical three-stage model, suggesting that at this difficult stretch of his life, Livingstone followed an atypical model in mediating and amending his thoughts. Far from being a raw record, for instance, the 1870 Field Diary shows Livingstone already planning future publications – though perhaps in a more critical vein than circumstances ultimately permitted.

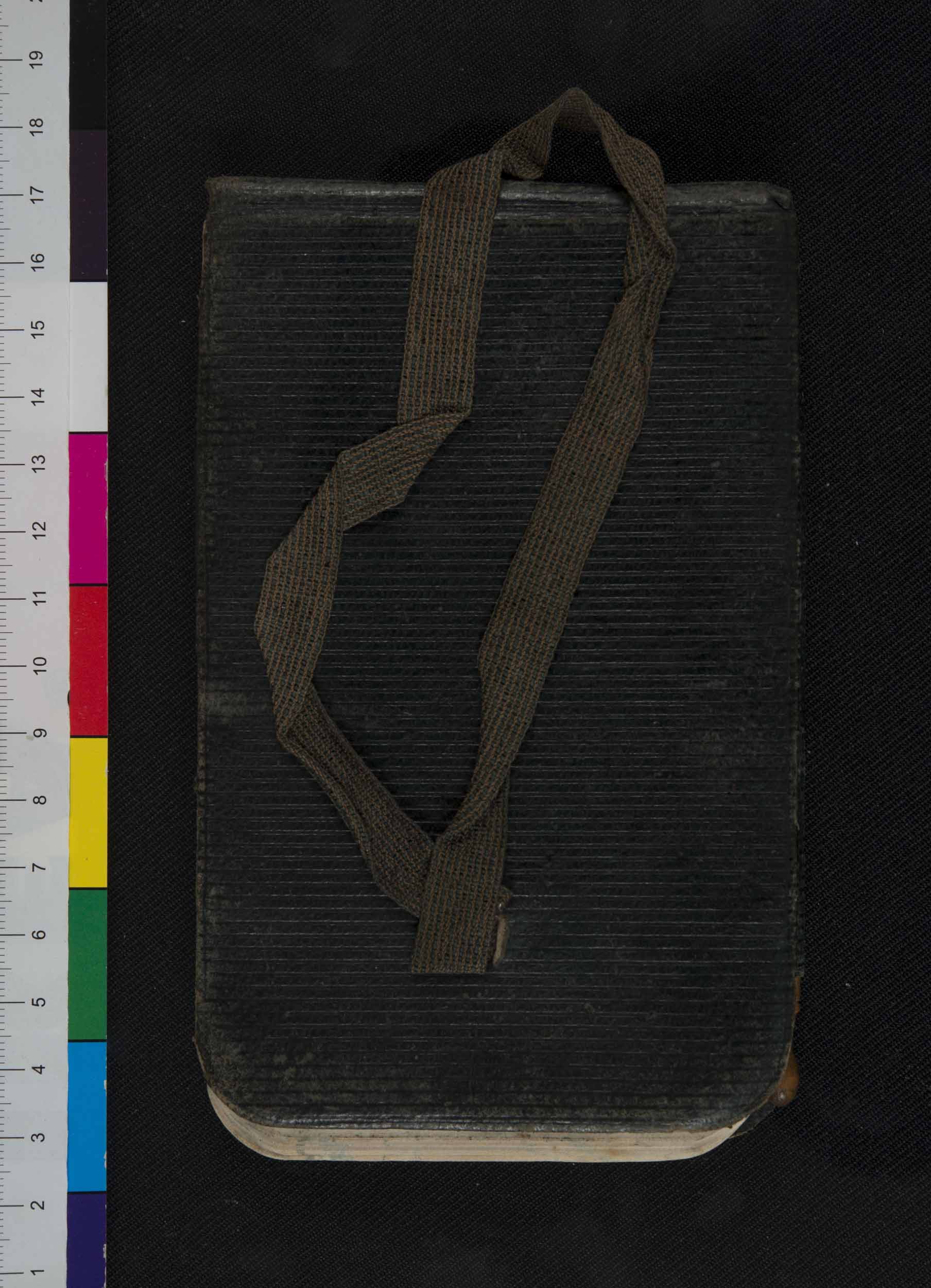

| (Left; top in mobile) The cover of Field Diary VII (Livingstone 1866f:1). (Right; bottom) The inside cover of Field Diary VII (Livingstone 1866f:2). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. Livingstone wrote Field Diary VII in the same kind of stenographer-style notebook that he used for Field Diary XIII. |

Entries in the handmade 1870 Field Diary tend to be longer and more sporadic, while Field Diary XIII, which Livingstone apparently composed concurrently, appears to keep track of dates and use shorter notations. As this was the last of the small stenographer notebooks that Livingstone had with him, he dramatically reduced his entries, presumably as he realized that he could not access the box in Ujiji.

Livingstone shifted from longer entries in the beginning of the notebook (June 1869-Aug. 1870) to short notations as he began to run out of space. He began using the notebook primarily to keep track of dates, often lining up the date numbers until something occurred that he deemed noteworthy. Instead of filling an entire page with one day, he shifted to recording the dates of many days, with only a scrawled word or two next to select dates. For instance, one line from August 1870 reads, “18th 19th high wind 20th 21st 22nd trowsers [sic] red made Susi idle.”

Events that Livingstone records in three separate phases, that is, in the two diaries and the journal, tend to be local events, especially illnesses, Manyema conflicts, and Livingstone’s frustrations with his own men. First he records an event in Field Diary XIII, then expands upon in the 1870 Field Diary and, later, revisits (and revises) it in the Unyanyembe Journal.

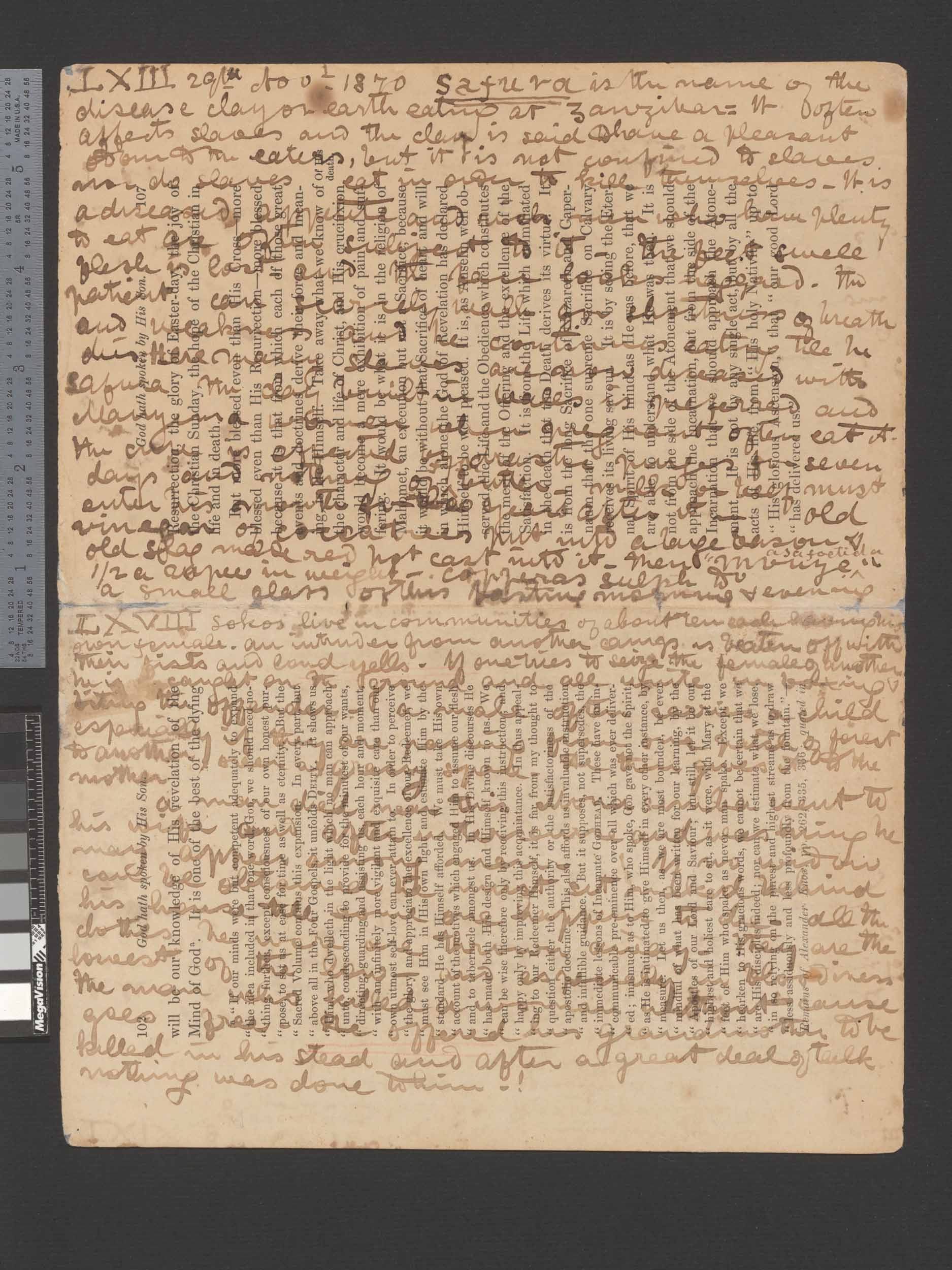

Bound pages from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870j:LXIII, LXVIII). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The page at top sets out Livingstone's observations on safura, a disease that involves eating earth, now known as pica or geophagy.

For instance, he briefly records “safura or clay eating” in Field Diary XIII (29 Nov. 1870). On the same date, he expands this in the 1870 Field Diary to a long entry on the “disease [of] clay or earth eating at Zanzibar,” noting that this affected slaves as well as pregnant Manyema woman. He concludes that “[s]afura is thus a disease per se” rather than some kind of attempt at suicide and so he feels “content” to wait until his medicines arrive so that he might try to augment the local cure of purging and fasting (Livingstone 1870j:LXIII).

The version he later recorded in the Unyanyembe Journal retains the medical evidence but edits out his own thoughts on potential cures, adding instead this anecdote: “Muhamad's brother was attacked and his wife told him of it on enquiry his brother was ashamed & denied it but his wife repeated - it is false he is constantly picking out earth out of the garden wall or little clods on the surface and eating them” (Livingstone 1866-72:[621]). In this instance, the 1870 Field Diary becomes more of an add-on to Field Diary XIII, expanding on something Livingstone noted but did not have the space to elucidate. The Unyanyembe Journal then revises it for a wider audience, removing Livingstone’s medical notes and adding more local color.

Documents of Varying Purposes Top⤴

This three-stage development – traditionally seen as typical for Livingstone – is actually unusual for these manuscripts. Instead, we see a variety of approaches, which treat Field Diary XIII and the 1870 Field Diary documents with varying purposes, rather than as the first- and second-stage documents described above. Some pieces of information appear only briefly in Field Diary XIII and nowhere else. Livingstone uses Field Diary XIII to record payments; once a month for August, September, and October 1870, he notes “beads” or “gave beads.” He also uses Field Diary XIII to record agricultural practices. For instance, on 23 December 1870, he writes “rice coming into ear,” while on 26 January 1871, he observes that the Manyema “planted beans & maize.”

Finally, he uses Field Diary XIII to keep track of comings and goings, noting when his men go out to find food and when they return, citing points such as, “Safari left today” (19 Oct. 1870) or “Nyumbo up Tombatu islet” (3 Nov. 1870). This is the daily business of being an explorer and provides important details from the life of someone conducting an expedition with hired labor and relying on local food sources. Livingstone never expanded upon or recopied much such information into other documents, at least in this stage in his travels.

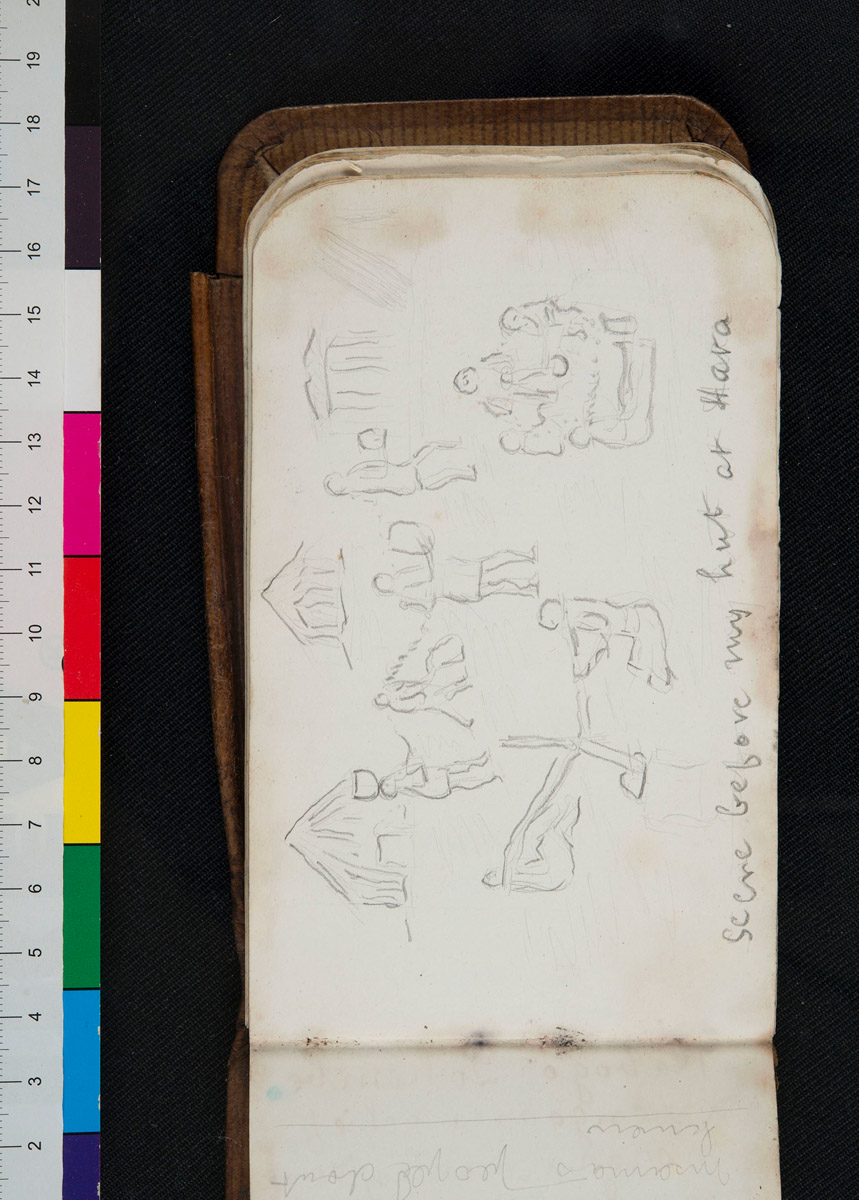

| (Left; top in mobile) A page from Field Diary X: 'Scene before my hut at Hara' (Livingstone 1867c:140). (Right; bottom) A page from Field Diary XIV (Livingstone 1871n:81). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The page for Field Diary X illustrates a village scene of the kind Livingstone might have encountered on a daily basis at Bambarre. The page from Field Diary XIV offers an example of Livingstone composing multiple short diary entries in a sequence, as he did in Field Diary XIII when he began to run short of space. |

Other kinds of information might warrant a brief entry in Field Diary XIII and then a revision or expansion in the 1870 Field Diary without being carried over to the Unyanyembe Journal. For example, in Field Diary XIII, Livingstone writes “Muenimgoi steals a captive and sells her back to Mocnemohia for 30 spears” (1 Nov. 1870). An entry in the 1870 Field Diary dated one day earlier, 31 October 1870, expands this event into a lengthy paragraph, explaining how Monangoi fits into the local kinship and governance networks. He laments the acceptance of what we would now call human trafficking, noting, “When asked about this captive he said ‘she died’ – It was simply theft – but he does not consider himself bad” (Livingstone 1870h:XIX). In this way, the 1870 Field Diary functions as a second-stage document, a place to expand upon events merely noted before and repackage them with Livingstone’s own interpretation.

In one instance, Livingstone even uses the 1870 diary for both first and second stages within the same diary. A draft copy of a letter to Lord Stanley appears in the middle of the second gathering of pages and summarizes Livingstone’s travels to-date in Manyema (Livingstone 1870i:XLI-LXI). In doing so, the letter offers a revised version of the narratives of both the first gathering and the second gathering up to the point where the letter appears. The result is a document integral to the diary that at the same time embodies a new stage of revision. This suggests that Livingstone doesn’t necessarily see each diary as a discrete manuscript but rather envisions a more fluid temporal relationship both among the diaries and even within them.

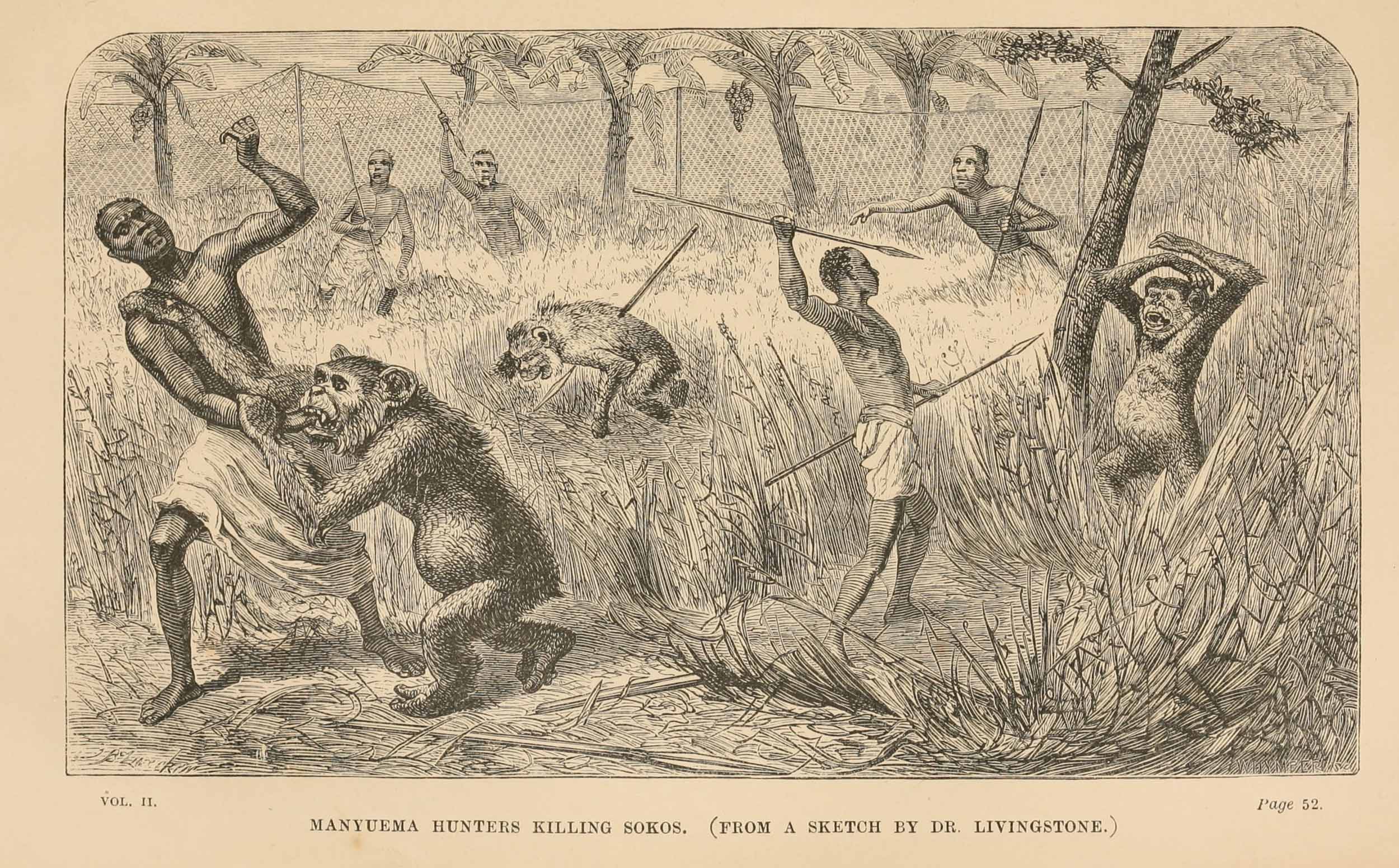

'Manyuema Hunters Killing Sokos. (From a Sketch by Livingstone.)' Illustration from the Last Journals (Livingstone 1874,2:opposite 52). Courtesy of the Internet Archive. Professional illustrations, such as this one, could differ considerably from the original sketches that the artists used as their source.

Most often, the 1870 Field Diary works like another first-stage document, recording new material alongside Field Diary XIII rather than amplifying it. Moreover, because of Livingstone’s atypical method in this case of carrying over passages from the 1870 Field Diary into the Unyanyembe Journal, the 1870 Field Diary occupies the unusual position of being first- and second-stage at once. Here Livingstone wrote several entries, spread over many months, on his experiences with an animal he calls a “soko,” a type of monkey.

Initially, Livingstone reports in August 1870 that the soko “takes away my appetite by his disgusting bestiality of appearance” (1870c:IV). By 1 March 1871, he has taken a female soko as a pet, and writes the she “holds out her hand for people to lift her up” and “comes and sits down on my mat beside me as a child would do” (1871e:XC). These accounts, which Livingstone never revised, were partially grouped together by Waller under a single section in the Last Journals (1874,2:52-55) and resulted in a posthumous contribution to African natural history in the Zoologist in 1875.

Unpublished Accouts Top ⤴

Certain accounts in the 1870 Field Diary, though, never went beyond its pages, as they were excised from the published version. Waller relied almost exclusively on the 1870 Field Diary when creating the published version, so the text that has been edited out is recorded nowhere else.

For instance, Livingstone complains at length with what he calls the “Nassick boys” or “Nassickers,” graduates of the government-run Nassick School for freed slaves in India. Livingstone states that the Nassick porters belong to “the lowest or criminal class in Africa” (1870b:[54]) and ascribes their poor behavior, including threats of mutiny, to the lax treatment at the Nassick school in India: “These might either work play or do nothing at Nassick & not one of them could handle a tool” (1870b:[53]). The problem, Livingstone concludes, is that “the teacher feared that if punished for idleness they would run away and bring discredit on the Asylum” (1870b:[54]).

| The recto and verso of a single leaf from the 1870 Field Diary, as written over a page margin cut from the Quarterly Review (Livingstone 1870b:[53]-[54]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. |

If, as Helly has described, Waller’s goal was to “preserve and protect Livingstone’s fame as the missionary explorer par excellence in order to use that fame as the basis for an antislavery crusade in East Africa,” it is perhaps no wonder that Waller omitted Livingstone’s opinion of both the institution of Nassick and its graduates (Helly 1987:163). But Livingstone evinced no such concerns by revising or omitting these complaints himself.

Similarly, when Livingstone’s men later mutiny, he writes in the 1870 Field Diary that, in order to restore order, “I had to treat them as slaves and promised on the word of an Englishman that I would shoot the ringleader against my orders” (1871b:LXXXV). This incendiary phrase is reduced by Waller in the Last Journals to a passive reference to using “fear of pistol shot” (1874,2:99). The Last Journals then completely removes from the 1870 Field Diary entry noting Livingstone’s conclusion that if his porters did not obey, “I would certainly shoot them” (1871b:LXXXVI). Though Waller may have seen these sentiments as politically liable, Livingstone had no compunction about recording such opinions and threats, suggesting that the 1870 Field Diary functions much more like Bridges’ “‘raw’” record than a second-stage document.

John Murray's estimate book showing the expected costs of publishing David Livingstone's Last Journals, 1874. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland

In addition, our critical edition provides access to the original version of a “Retrospect” from March 1870 that Livingstone recopied in the Unyanyembe Journal (1870a). This free-floating piece predates the 1870 Field Diary, but works like it in that Livingstone intended it “to be inserted in the Journal if I get back to where it is left in Ujiji” (1870a:[1]). Livingstone opens the piece by musing on his missionary career. He concludes that, though he had been criticized for his failures to convert local African populations, he has no regrets except for the treatment of his family: “Though conscious of many imperfections not a single pang of regret arises in the review of my conduct except that I did not feel it to be my duty while spending all my energy in teaching the heathen, to devote a special portion of my time to play with my children” (1870a:[1]).

This highly personal meditation responds to public critique that Livingstone sacrificed his family for personal gain. That Livingstone recorded it in early 1870 and then expressly recopied it in the Unyanyembe Journal at a later date suggests that the two texts serve different functions for Livingstone.

Conclusion Top ⤴

Ultimately, by reading Field Diary XIII, the 1870 Field Diary, and the Unyanyembe Journal as overlapping documents, we can see how Livingstone used the materials available to him to create a record without the sequentially staged documents he employed at other points in his career. For this time period, Livingstone is not composing in stages but venturing on a new composition practice out of necessity.

Creating the 1870 Field Diary as he goes, using Field Diary XIII in a very limited way, and with thoughts of developing future records in the Unyanyembe Journal if he makes it back to the Ujiji, the conditions of Livingstone’s exploration shape his composition practices. The existence of these varying manuscripts act as their own record of Livingstone’s experiences, as much as what he wrote down. That these documents do not always conform to the typical three-stage model suggests that we must mine all levels of textual production to understand how material conditions affected the imperial record, rendering it heterogenous, partial, and often incomplete.

Works Cited Top ⤴

[View the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project's full bibliography.]

Bridges, Roy C. 1977. “The Documentation of David Livingstone: Some New Materials.” Hakluyt Society Annual Report and Statement of Accounts 1977-1978, 1-8.

Bridges, Roy C. 1998. “Explorers’ Texts and the Problem of Reactions by Non-Literate Peoples: Some Nineteenth-Century East African Examples.” Studies in Travel Writing 2: 65-84.

Helly, Dorothy O. 1987. Livingstone’s Legacy: Horace Waller and Victorian Mythmaking. Athens, OH, and London: Ohio University Press.

Jeal, Tim. 2013. Livingstone: Revised and Expanded Edition. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1973.

Koivunen, Leila. 2009. Visualizing Africa in Nineteenth-Century British Travel Accounts. London: Routledge.

MacLaren, I.S. 1992. “Exploration/ Travel Literature and the Evolution of the Author.” International Journal of Canadian Studies 5: 39-68.

Wisnicki, Adrian. 2013. “Victorian Field Notes from the Lualaba River, Congo.” Scottish Geographical Journal 129: 210-39.

Youngs, Tim. 1994. Travellers in Africa: British Travelogues, 1850-1900. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press.

![Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_013723_0001-new-carousel_0.jpg)

![Processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's "Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal" (Livingstone 1870a:[3] pseudo_v4_BY), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's "Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal" (Livingstone 1870a:[3] pseudo_v4_BY), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000211_0003_pseudoBY_940_by_592-carousel.jpg)

![David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, [1869], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland: CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, [1869], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland: CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_003006_0001-new-carousel_0.jpg)

![A page from the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[625]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). A page from the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[625]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/livingstones-composition-practices/liv_000019_0625-article.jpg)

![A page from the 1870 Field Diary, as written over a page margin cut from the Quarterly Review (Livingstone 1870b:[53]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). A page from the 1870 Field Diary, as written over a page margin cut from the Quarterly Review (Livingstone 1870b:[53]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/livingstones-composition-practices/liv_000200_0053_color-article.jpg)

![A page from the 1870 Field Diary, as written over a page margin cut from the Quarterly Review (Livingstone 1870b:[54]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). A page from the 1870 Field Diary, as written over a page margin cut from the Quarterly Review (Livingstone 1870b:[54]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/livingstones-composition-practices/liv_000200_0054_color-article.jpg)