Reading Exploration Through the Digital Library

Cite page (MLA): Simpson, Kate. "Reading Exploration Through the Digital Library." Justin D. Livingstone et al., eds. Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. University of Maryland Libraries, 2017. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/87e5d1e8-7adf-4a5a-b17c-004b3ceac371.

This essay outlines the significance of Livingstone Online as a digital library. Using examples from the site, the essay examines the importance of the digital library in continuing the deconstruction of persistent, individual-centered histories of nineteenth-century exploration in Africa, and explores the implications of such work for the rediscovery of lost, silenced, or muted narratives in the historical record.

Introduction Top ⤴

In a diary entry written close to the very end of his life in April 1873, David Livingstone mentions a little girl who has joined his expedition. He writes about how she has been able to keep up because she “walks wonderfully,” and how he, upon finding out she is part of the group, sends extra food to her as she has been “weakened greatly” by the starvation his party was enduring whilst they were mired in the Bangweulu wetlands of modern day Zambia (Livingstone 1872h:[162], [163]).

This short entry did not make it into Livingstone’s posthumously published Last Journals (1874), but it allows insight into the lived reality of travel in nineteenth-century central Africa. The little girl merits just over a page in Livingstone’s diary, and we do not even know her name, let alone what subsequently happened to her when Livingstone died, yet this elusive mention strikes at the very heart of the potential of a digital library like Livingstone Online. In gaining access to information previously erased during publication, a user can read against the grain of the published historical record and recover other perspectives and voices, even if only partially. The little girl is a token of the richness contained within the manuscripts held by Livingstone Online.

| Two pages from David Livingstone, Field Diary XVI (1872h:[163], [162]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, University of Glasgow Photographic Unit, and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. Livingstone's field diaries often contain material omitted from his published accounts. These pages, for instance, record Livingstone's unpublished discovery that a young, unnamed girl has joined his party. |

Livingstone Online heightens what can be achieved archivally: as a digital library, the site successfully integrates the traditional split between the sequestered archive and outward-facing library, and acts as both a historical knowledge repository and as an information centre open to individual needs, reconfiguration, and scrutiny. “By transforming and recontextualizing archival objects,” James Mussell suggests, “digitisation also offers the possibility that they may be reinterpreted, anchoring a new set of histories” (2014:383). Thus, as with the little girl, users can find new knowledge in old manuscripts.

The digital library facilitates the creation of new histories and new narratives. The little girl was not part of Livingstone’s initial expeditionary party, yet users are able to have a glimpse of her unique journey during the time that it coincides with Livingstone’s. It is not that the digital library allows access to a wholly new and complete history, but rather the digital library provides a new way to explore the histories to which we already have access.

Statue of Africans carrying David Livingstone's embalmed body, Blantyre, Scotland 2017. Copyright Adrian S. Wisnicki. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. This statue, at the train station in Blantyre, points visitors in the direction of the nearby David Livingstone Centre. The statue offers an example of how Livingstone's narrative continues to be reinterpreted in the present day.

For many years scholars and researchers have worked to break down the dominant Victorian representation of explorers like Livingstone and the expeditions they led. As Dane Kennedy writes, the “heroic individual has long loomed large in the literature of exploration” (2014:3). In other words, scholarly focus on individuals has overshadowed attention to complex histories of interaction among people and cultures. Although Livingstone showed incredible drive and fortitude, he worked as part of different teams, often large in number, who strove collectively to overcome obstacles they faced in the course of expeditions.

Roy Bridges notes that for over one hundred years explorers’ writings were regarded as “authoritative statements on Africa and Africans” (1998:66). These seemingly “authoritative statements” are, however, reflective of the western imperial ideology out of which they came and cannot be said to speak for the people they describe. What Bridges and Kennedy highlight is a growing emphasis on breaking down these individual-centered narratives to show the full cultural and societal complexity of the Victorian exploration of Africa.

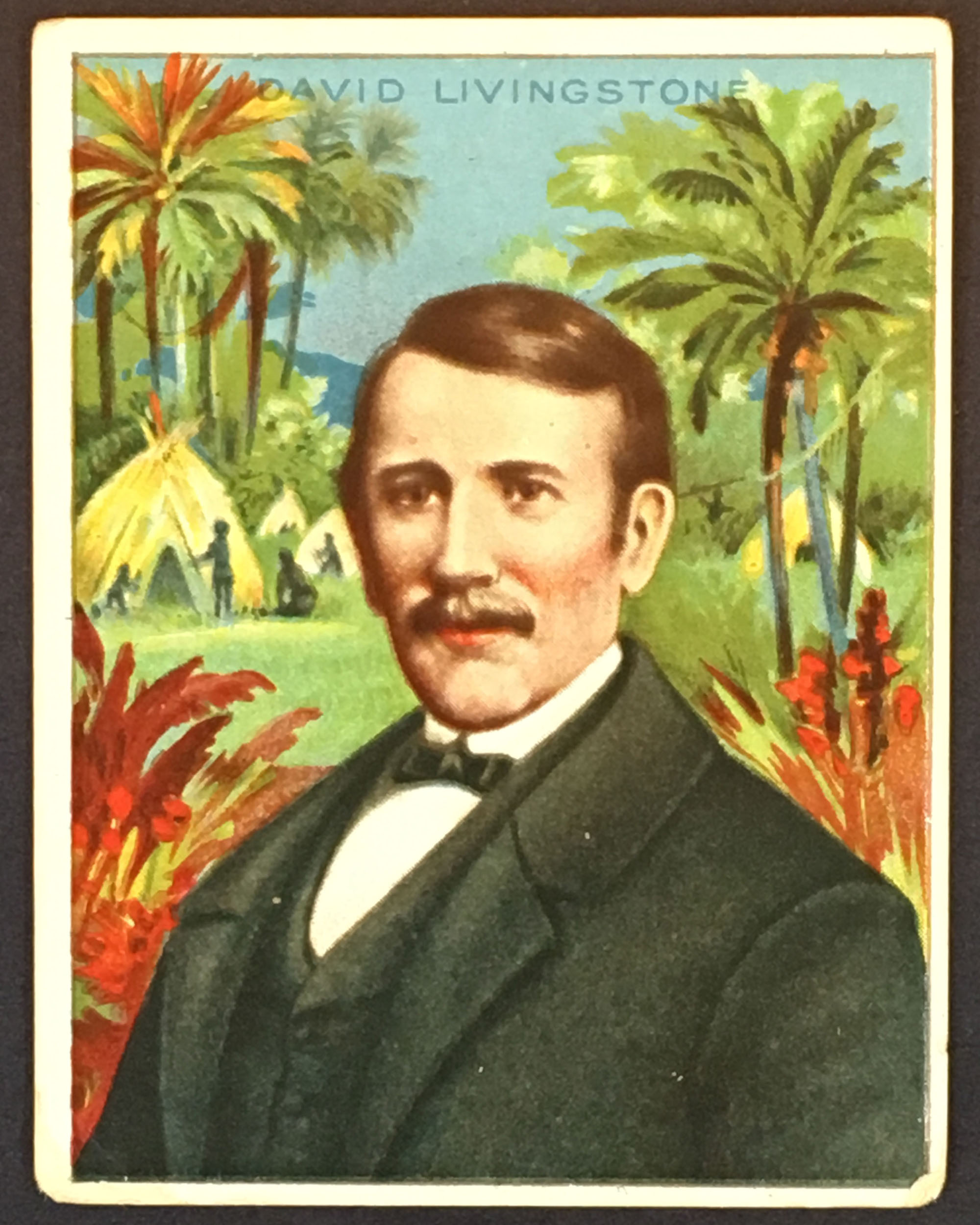

| Greatest Explorers Tobacco Trading Card: David Livingstone, 1910, recto and verso. Image copyright Adrian S. Wisnicki. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. Artifacts such as this card testify to Livingstone’s ongoing popularity in the early twentieth century. |

Not only have researchers sought to revisit interpretations and representations of the European role in exploration, but postcolonial scholars have raised questions about the participation of African peoples and their depiction in such narratives. Elias Mandala argues that “researchers, past and present, have continued to read a two-sided history from the European and English-speaking side only” (2014:15-16). The digital library addresses these important scholarly concerns by unearthing information that reveals different stories about the cultural exchange of exploration, which stand in contrast to the often imperial, colonial, racist, or misogynistic ideologies that appear in Victorian printed texts.

Indeed, the digital library is enlarging and accelerating the substantial reappraisal of European explorers and exploration. As was the written account, so the digital library is a stage in the development and transformation of the historiography of nineteenth-century exploration. Unlike the written record, the digital library enables the user to search for information in nonlinear ways, looking to identify new meanings from patterns that previously could not be seen in explorers’ original documents. Such searching often reveals complexities lost in the official published expeditionary narratives.

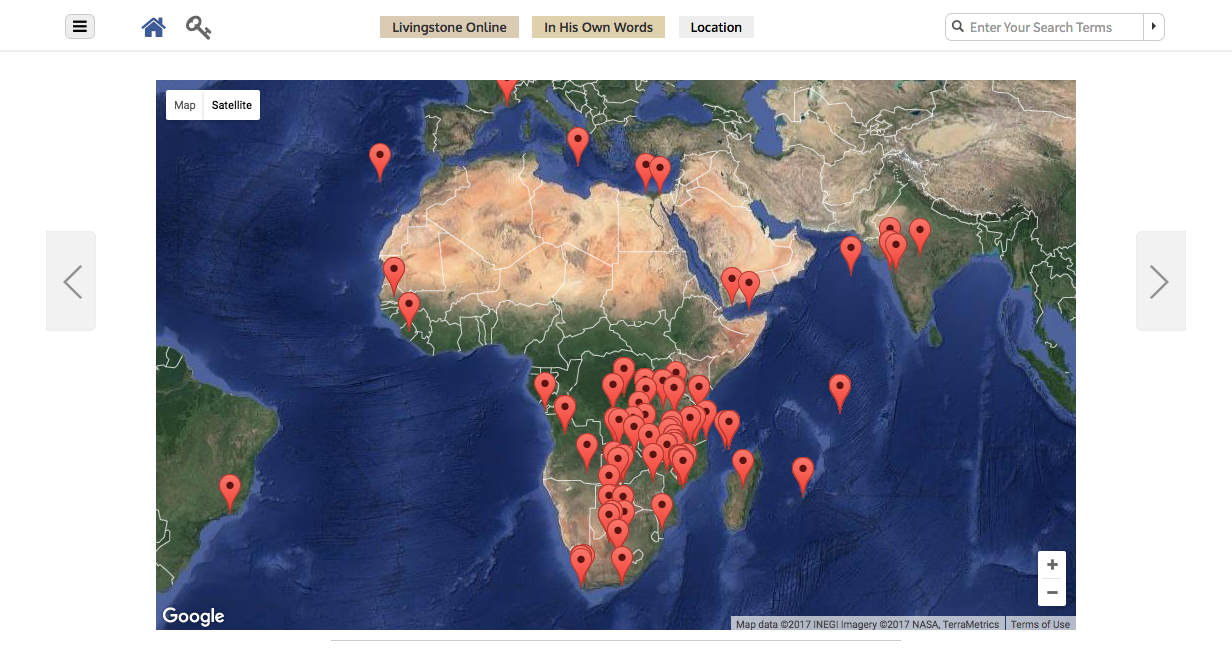

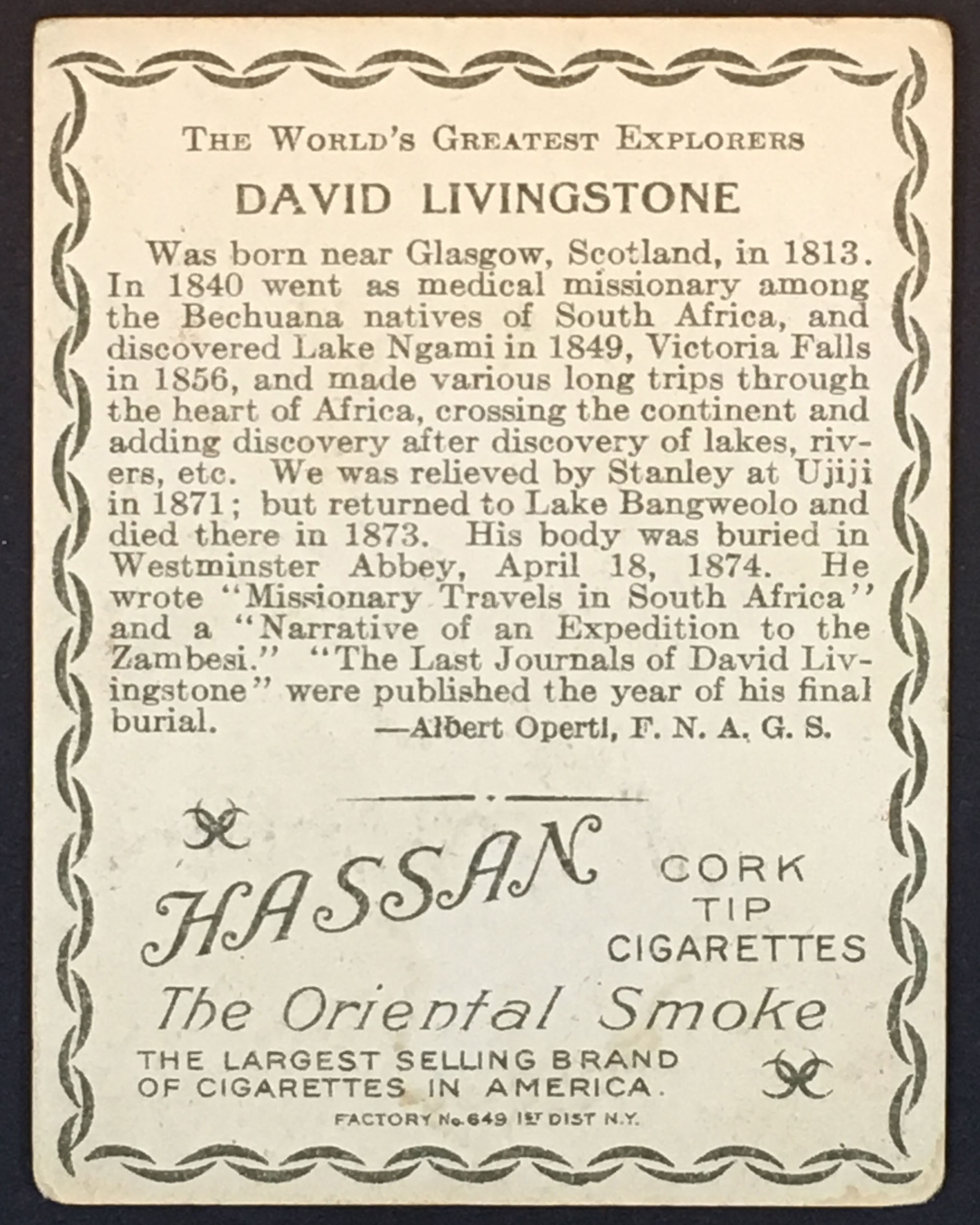

(Top) Screenshot of Livingstone Online's 'Browse by Timeline' page. (Bottom) Screenshot of Livingstone Online's 'Browse by Location' page. Copyright Livingstone Online. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. Livingstone Online enables users to browse the site's digital collection by date and place, thereby opening new ways for understanding the materials published by the site.

Livingstone Online, as a digital library, allows access to previously inaccessible information and facilitates scholarship that formerly would not have been possible on nineteenth-century exploration. The infrastructure of the site is open, the scholarship is peer-reviewed, and the bibliographic documentation aims towards comprehensiveness: even if a document is unavailable, its existence is acknowledged. Livingstone Online steps back from trying to be prescriptive and selective, and instead presents Livingstone’s African travel record as fully as possible.

Livingstone Online also places Livingstone’s original manuscripts in front of the user, in the form of high-resolution images, including spectral images. Users thus gain unmediated access to primary documents and to critically edited and encoded transcriptions. The site frames these materials with critical essays and varied historical illustrations, while also providing rich documentation in the form of process narratives, images, and project documents related to its, the site’s, own construction.

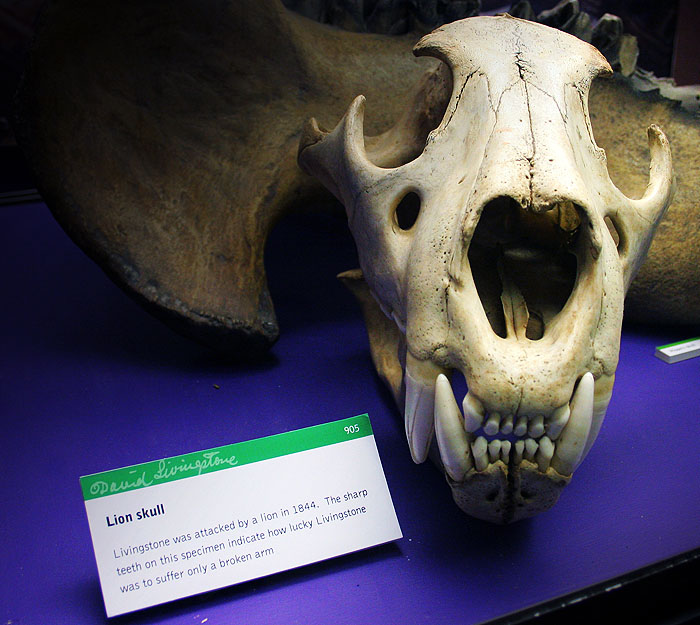

Lion skull, c.1800-1900. Copyright Livingstone Online. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. This skull comes from a display at the David Livingstone Centre. The use of this skull in the exhibit demonstrates how contextual objects, which have no specific historical relation to Livingstone, can nonetheless be drawn into the orbit of his narrative and so be given new meaning.

These and other such practices evidence Livingstone Online’s attempts to make the configuration of knowledge horizontal rather than hierarchical and so not constrained by prescriptive editorial judgements. As such, Livingstone Online engenders a nuanced reading of the narrative of day-to-day exploration, life, and travel – a reading that is more ambiguous and complex than Victorian representations of nineteenth-century historical figures (and scholarship that draws primarily from such representations) would suggest.

Although we may never know the name of the little girl who appears in Livingstone’s diary, we have at least been able to acknowledge her existence within the expeditionary group. Having been previously scrubbed from the published record of exploration, she has been brought back into the narrative; indeed, the recovery of her forgotten presence provides a glimpse of the previously muted details that can be extracted from the primary records held in the digital library. In offering access to such excluded stories, Livingstone Online serves to enrich our reappraisal of the intercultural interactions of European expeditions in Africa.

First Record Top ⤴

In the nineteenth century only a percentage of what Livingstone recorded was revised, rewritten, and made available for publication. In writing expeditionary narratives, explorers such as Livingstone often had particular agendas and were sensitive to the interests and demands of their reading public. In Livingstone’s case, his principal objectives were to attract British interest in Africa and, particularly, to motivate missionary and commercial ventures.

![Image of a page from David Livingstone, Letter to Klaso Whitboy, 4 August 1841:[1]. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, University of Glasgow Photographic Unit, and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). Image of a page from David Livingstone, Letter to Klaso Whitboy, 4 August 1841:[1]. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, University of Glasgow Photographic Unit, and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/about-this-site/reading-exploration-through-the-digital-library/liv_000486_0001-article.jpg)

Image of a page from David Livingstone, Letter to Klaso Whitboy, 4 August 1841:[1]. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, University of Glasgow Photographic Unit, and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported.

The significant amount of the original record which did not make it through the publishing process, then, can provide an expansive insight into the physical and cultural environment of British imperial expeditions, particularly those elements that were later deemed irrelevant to Livingstone’s main discursive goals. Accordingly, it is the unrevised information in the digital library which can provide new and unexpected information to the present day scholar.

The imperative of British explorers – often at the behest of organizations such as the British Government and institutions such as the Royal Geographic Society and the London Missionary Society – was to record as much information as possible about the lands, different individuals, and societies they encountered.

Livingstone went well beyond most explorers in the extent of his observations, not only because he was in Africa for a longer total period of time, but also in the sheer volume of information he recorded. In his nearly thirty years in Africa, Livingstone never stopped documenting what he observed and heard around him.

Wooden box of David Livingstone's letters at SOAS, University of London, c.2010. Copyright Livingstone Online. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. This box presents a striking example of how the Livingstone mythos has followed his manuscripts into the archive.

When explorers first wrote about an event, whether that be in a notebook, field diary, journal, or in a letter to a friend or colleague, that earliest telling often became an “irredeemable record” of their initial understanding of the acts, aspects and sense of an event (Battles 2013). This first written account of an event thus serves an irreplaceable primary record; the account is that person’s most immediate representation of an event and the source from which future interpretations are taken, derived, or adapted.

Although first records are still culturally-biased documents, unvarnished first records can reveal more about events than subsequent retellings. The user is able to be a secondary observer to the primary observations – like Livingstone himself when he uses primary documents as the basis for revised versions. If users can thus access the first recording or “raw” record of an event, as they can through a digital library like Livingstone Online, they can then begin to reanalyse the expedition in ways which the published texts, as invocations of Victorian social and cultural bounds, have not allowed.

![Image of two pages from David Livingstone, Field Diary, 23 August 1862-19 March 1863:[55]-[56]. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/). Image of two pages from David Livingstone, Field Diary, 23 August 1862-19 March 1863:[55]-[56]. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/).](/sites/default/files/about-this-site/reading-exploration-through-the-digital-library/liv_003008_0055-0056-article.jpg)

Image of two pages from David Livingstone, Field Diary, 23 August 1862-19 March 1863:[55]-[56]. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland.

These first recordings are vessels which not only hold textual information, but capture a sense of time, event, and place. As such the “raw” record is then an item of cultural property, increasing in value from the printed and published text by its artefactual and informational worth. The “‘raw’ records” not only offer evidence of the “explorer's immediate reaction to his experiences,” but through them the user can see what was left out of the published record (Bridges 1987:180).

By providing online access to substantial “raw” records, Livingstone Online facilitates a nuanced rethinking of the colonial narrative of European exploration in central and southern Africa. With this record, critics can then “construct a more multilayered model of imperial narrative production” (Wisnicki 2010:3). Fundamentally, access to original materials through Livingstone Online enables the user to generate new questions about exploration and its published record.

The Transition from Physical Object to Digital Content Top ⤴

Livingstone Online changes how we read Livingstone’s words by creating an infrastructure which refuses to privilege any particular portion of the corpus. Users can immerse themselves in Livingstone’s manuscripts, reading across the content held in multiple archives while surrounding themselves with the contextual information often needed to explain or expand on Livingstone’s primary texts.

![Livingstone Online spectral image viewer showing color and processed spectral images of a page from David Livingstone, 1871 Field Diary (1871l:[2] color and pseudo_v1). Copyright Livingstone Online and David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). Livingstone Online spectral image viewer showing color and processed spectral images of a page from David Livingstone, 1871 Field Diary (1871l:[2] color and pseudo_v1). Copyright Livingstone Online and David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/about-this-site/reading-exploration-through-the-digital-library/spectral-image-viewer-screenshot-article.png)

Livingstone Online spectral image viewer showing color and processed spectral images of a page from David Livingstone, 1871 Field Diary (1871l:[2] color and pseudo_v1). Copyright Livingstone Online and David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. These spectral images highlight the original fuction of Livingstone's text as an envelope.

By presenting critically encoded versions of texts beside their original sources (i.e. images of the physical manuscripts) and providing contextual materials, the site enhances the encounters of users with these primary documents. The site enables the texts, and the information about those texts, to be interrogated across numerous sources, in ways that can meet diverse needs. The site also signals the material contexts of the manuscript sources in ways often glossed over in physical publications. By viewing image of the physical entities, users are able to gain insights otherwise unavailable about the material conditions of production.

For example, users can read the published version of Livingstone’s Last Journals (1874) alongside the transcription of the original field diaries to identify the changes made during the editorial process, or users can view the original field diaries with transcriptions of those field diaries to facilitate a detailed inspection of the physical page, or they can read an assortment of critical essays on Livingstone’s final manuscripts to understand the importance of those manuscripts historically. In these instances and others, Livingstone Online facilitates multiple and varied encounters with Livingstone’s primary materials.

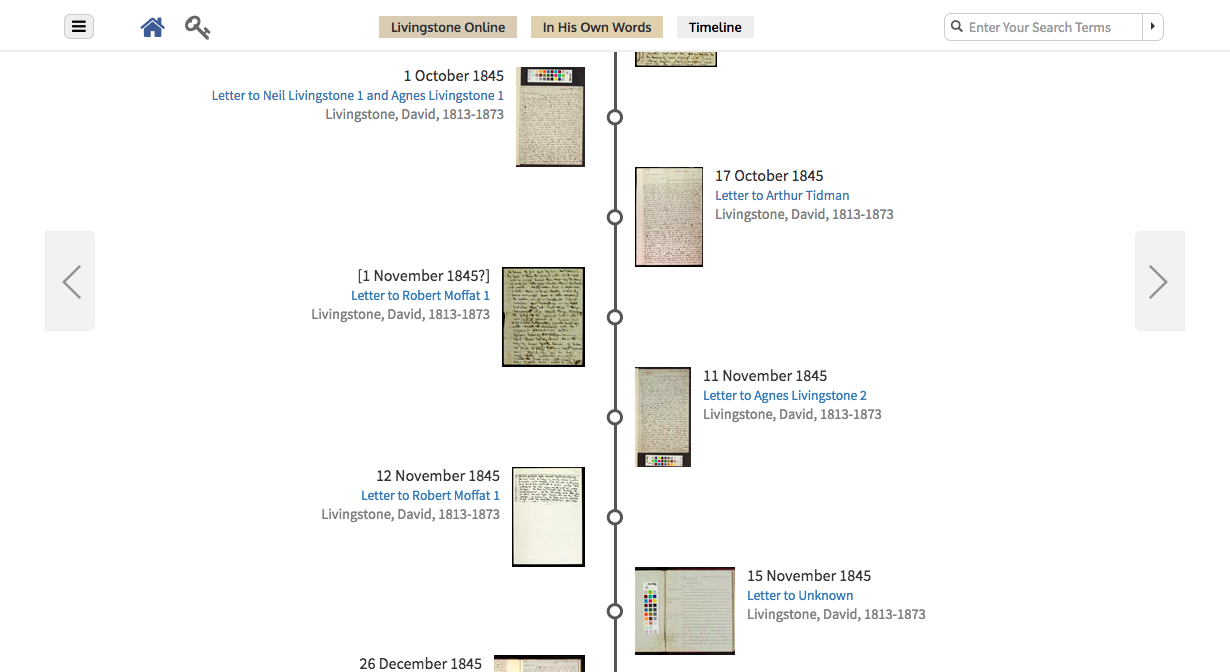

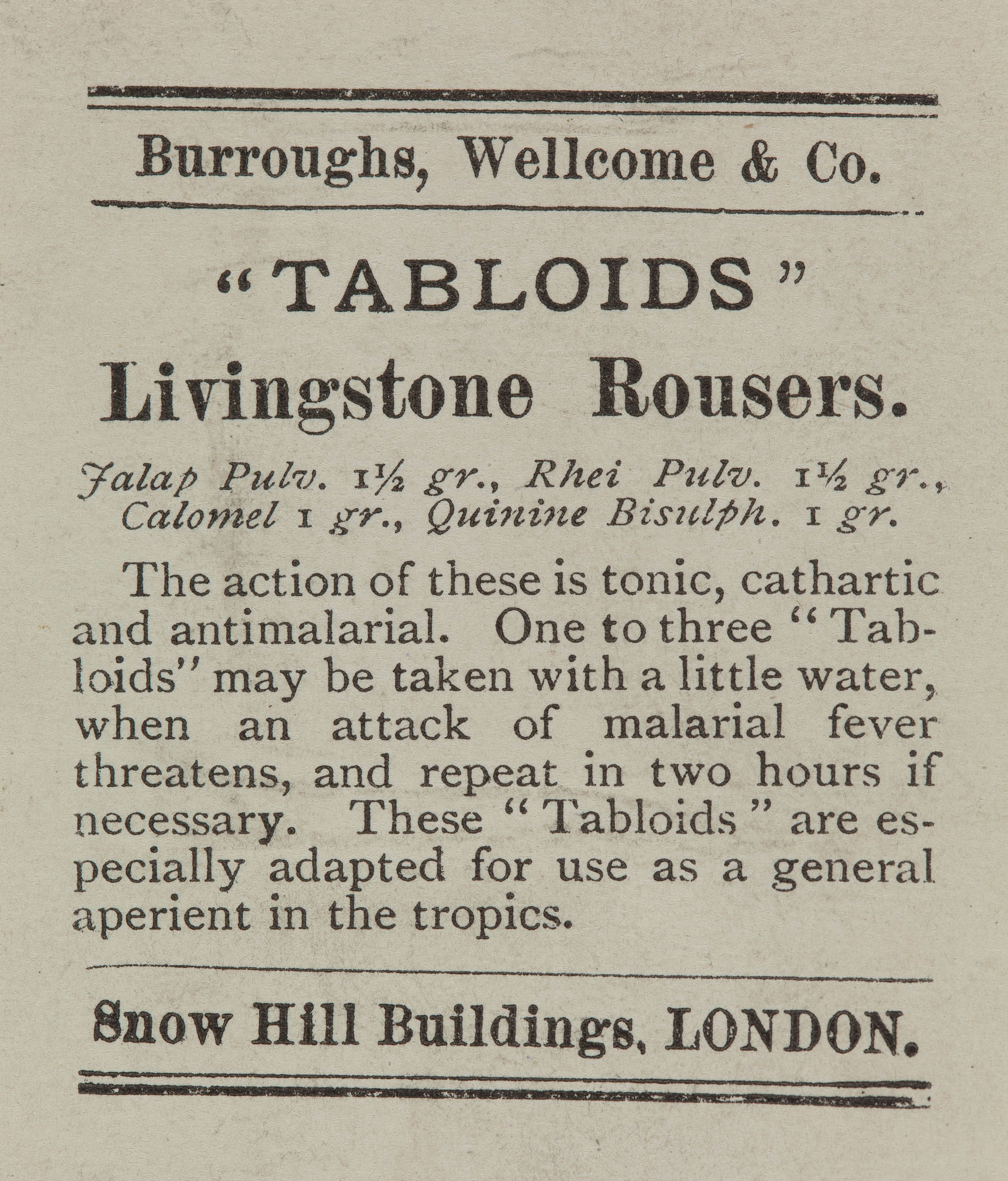

| (Left; top in mobile) Livingstone's Rousers. Copyright Livingstone Online. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. (Right; bottom) Pharmaceutical advert for 'Tabloids' Livingstone Rousers. Copyright Wellcome Library, London. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. These items exemplify how Livingstone's celebrity status as an explorer could be leveraged for economic interests. |

By providing such rich detail the digital library is unique. Viewing the primary documents enables users to have a visceral engagement with the architecture of the written record of exploration.The tangible physicality of a battered and bruised field diary that has, for example, been carried in a rusting box, kept in a pocket, drenched in rain, or used as a specimen holder, is made visually available to users for their own close analysis. Livingstone Online allows users to see the whole document as the scholarly object, not just the words on the page. By confronting the materiality of the page, users can engage with a form of study not previously possible when consulting print materials.

In many ways the digital nature of the record enables users to explore the repository, using the embedded information in ways that the Victorian originators of the printed record did not intend. In doing so, users can experience the richness and value of the primary physical archives themselves. The new perspectives opened through this process ultimately provide for a more substantive reading of the primary materials of British exploration.

Reading Missionary Travels through the Digital Library Top ⤴

The vast quantity of information that a digital library like Livingstone Online can give is not isolated to Livingstone’s journals, notebooks and field diaries, but also extends to his book manuscripts. Such manuscripts offer a window into Livingstone’s authorial intentions and the process of crafting his narratives, or what one scholar describes as Livingstone’s “self-projection and impression management” (Livingstone 2014:20). Through Livingstone Online, users are able to trace the development of topics that Livingstone felt were important in understanding his role as a missionary and explorer, including his belief in the role of commerce and economics in eradicating slavery in Africa.

One such example appears in the manuscript of Livingstone’s first book Missionary Travels (1857). The images below (of pages from the original manuscript that did not make it into the published text) show how the chance to examine redactions for the book can alter the prevailing, popular image of Livingstone. Livingstone’s discussion of British involvement in Xhosa, Zulu, Boer and colonial land wars in South Africa reveals that in the first draft of the manuscript Livingstone was aware of and uncomfortable about the vast profits that “English commerce derived” in “goods bought from the Colony” (Livingstone 1857b:[262]).

![Image of a page from Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa (Part I), January-October 1857:[255]. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/). Image of a page from Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa (Part I), January-October 1857:[255]. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/).](/sites/default/files/about-this-site/reading-exploration-through-the-digital-library/liv_000099_0255-crop-article.jpg)

Image of a page from David Livingstone, Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa (Part I), January-October 1857b:[255]. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. Access to an image of the original page like this reveals features that would be lost in any published version, such as the interaction of many hands in shaping Livingstone's manuscript and the legibility challenges created by the binding of the original artifact.

This original text enables the user to gather a much more rounded understanding of Livingstone, his political beliefs, and the contexts in which he worked. Importantly, the text provides further evidence of Livingstone’s understanding that, until other forms of commerce could be created, it would be impossible to eradicate the economically valuable slave trade in Africa. The passage also evidences Livingstone’s unease at the eighth Xhosa-British war of 1852-1853. He writes, “It cost us upward of £2,000,000 and the only thing we have to show for the money is a monied community” (Livingstone 1857b:[263]).

Yet in the final published version of Missionary Travels these sections, which could give users a greater understanding of Livingstone’s interpretation of the colonial situation in southern Africa, were removed. It was, as Justin Livingstone notes, “a massive act of editing” [in that] “before publication [Livingstone] removed more than twenty pages in which he had criticised the abuse of martial power, the infringement of African rights, and corruption at the Cape” (2014:39). Livingstone Online enables users to undo this “act of editing” and to see the manuscript’s original characteristics and its author’s composition strategies.

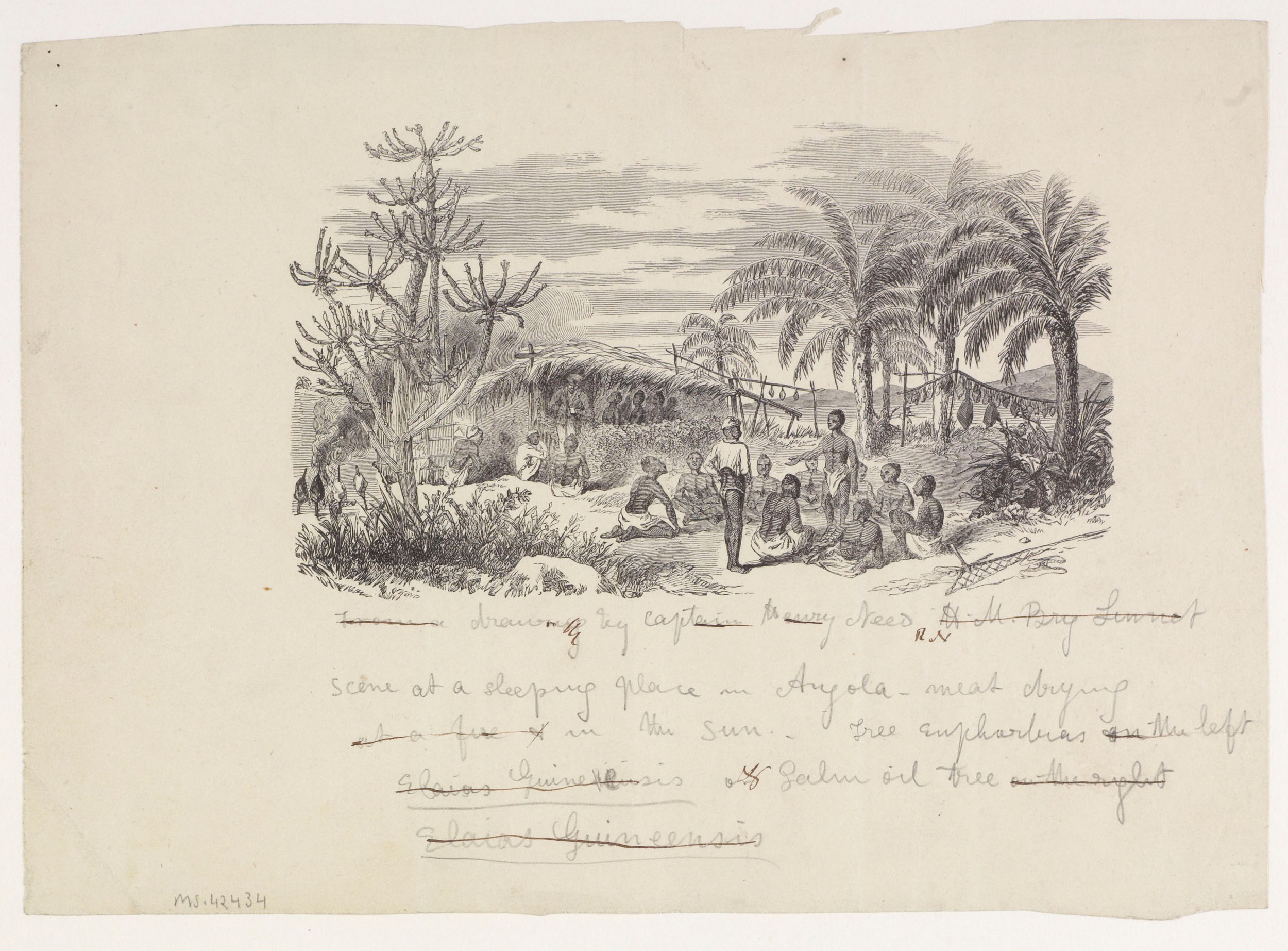

Marked Proof Engraving of Scene at a Sleeping-Place in Angola: Illustration for Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa, 1856-57. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. The images that appeared with Livingstone's published works could also be subject to significant revision, as in this case.

Such comparative readings are not only made easier by the digital interface, which shows both published text and manuscript simultaneously, but by the digital library as a whole in bringing together sources held in geographically separate repositories. By aggregating sources the digital library encourages comparative engagement. In this instance the redacted text shows users that Livingstone was not just an explorer and missionary focussed on his own journey, but had a deep understanding of the difficulties created by multiple cultures inhabiting the same physical space. The published version, which is also made available through Livingstone Online, in turn reveals how Livingstone reworked his original ideas for public consumption. Being able to discover Livingstone’s understanding of the economics of a colonial war through the material on Livingstone Online gives users greater insights into the rationale behind Livingstone’s actions and statements, in ways that go beyond the insights offered by the published text.

Reevaluating the Physical Page Top ⤴

Livingstone’s narratives are often found in their “rawest” form in his field diaries, which he kept while traveling when time to record impressions was limited. As such, the field diaries often serve as untapped data sources for the economic and situational aspects of Livingstone’s expeditions – data that could be omitted in, or was not available for, published sources. For instance, the primary field diaries from 1866 to 1871 “were stored in a box at Ujiji’ [and only] reached England in late January 1875, after the initial publication of the Last Journals of David Livingstone” (Helly 1987:65).

![Page from David Livingstone, Field Diary I (1865:[91]), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, University of Glasgow Photographic Unit, and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). Page from David Livingstone, Field Diary I (1865:[91]), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, University of Glasgow Photographic Unit, and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/about-this-site/reading-exploration-through-the-digital-library/liv_000001_0091-crop-article.jpg)

Page from David Livingstone, Field Diary I (1865:[91]), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, University of Glasgow Photographic Unit, and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The insect, now an intrinsic part of the expeditionary record, provides unique information about the environment in which the diary was written.

Field Diary I (Livingstone 1865) evidences the type of data that could be omitted from the public record. Page [89] shows that Livingstone paid Theodor Schulby the large sum of £27 and four shillings to keep buffalo. Livingstone also paid a havildar (an Indian sergeant) five rupees for grass for his buffaloes and mules, and an extra five rupees for cattle feed. Although none of these details are significant of themselves, together and in context the details provide valuable data on the kinds of animals used by Livingstone’s expedition and the economic costs of maintaining these animals. The details also raise questions about the makeup and accumulations of those costs.

But it is the physical manuscript page itself, in which these details are embedded that provides the most intriguing information. In this case, a small insect is affixed to the page – an insect which has now become intrinsically part of the record of exploration. The insect might have flown between the pages by chance just as Livingstone was closing his notebook or crawled in when he had set the diary down somewhere. Alternatively, Livingstone might have trapped the insect between the pages himself. Whatever the case, the presence of the insect shows that access to the physical page offers the potential for unique glimpses into environmental contexts in which the narrative was produced.

| (Left; top in mobile) Image of a page of David Livingstone, Field Diary VI (1866e:[36]). (Right; bottom) Image of a page of David Livingstone, Field Diary V (1866d:[77]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, University of Glasgow Photographic Unit, and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. These pages demonstrate two ways by which flora from the environments through which Livingstone traveled could interact with his manuscript pages. In the first image, the illustration on the written page traces the contous of the object that has been placed on the surface. In the second image, it appears that the addition of the object to the diary has led to significant staining of the page surface. |

Indeed, the insect provides a vivid example of information as yet untapped in the digital library. In this way, Livingstone Online enacts a kind of scholarly publication in which the whole document, in its physicality, can be studied. The chance to view the document in its entirety enables the user to engage with an item’s origins and its physical archaeology. Ultimately, the field diaries evidence the constructed, ever evolving nature of the narratives that Livingstone composed and the material contexts in which he composed them.

Exploration Examined Top ⤴

Livingstone Online thus allows for the examination of what we now recognize as important, but often untapped historical information. Such data can also include the names, roles, and functions of non-western populations within the expedition group. Livingstone often records these elements in detail – even if this information was not prioritised in his published books, which were eagerly read by the Victorian public.

Yet this information is important to our understanding of British exploration. Crucially, the material shows the degree to which expeditions were group efforts. As Felix Driver notes, the details revealed in primary documents enables questions to be raised regarding “what was made visible and what was obscured in standard narratives of exploration, especially when seen from a British perspective; specifically, whose labours come to be recognised as indispensable to the process of exploration and whose are marginalised?” (2013:421).

For example, for the period of 15 to 17 August 1872, the published text of the Last Journals (1874) presents the following:

15th August.—The men came yesterday (14th), having been seventy-four days from Bagamoio. Most thankful to the Giver of all good I am. I have to give them a rest of a few days, and then start.

16th August.—An earthquake—“Kiti-ki-sha!”—about 7.0 P.M. shook me in my katanda with quick vibrations. They gradually became fainter: it lasted some 50 seconds, and was observed by many.

17th August, 1872.—Preparing things.

Yet in the corresponding section of the field diary for these dates there follow five pages of additional information, including a detailed list of porters, their names, and items transported by each of them (Field Diary XV, 0030, 0031). The list includes individuals such as Farahame, who carried Livingstone’s tool box; Namuri, Bilale and Mabruki, who all carried boxes of ammunition; Maganga, Musa, Baraka, Suedi and Hamade who carried brass wire; Gardner, Kendette and four others who carried beads; and so forth.

| Images of three pages of David Livingstone, Field Diary XV (Livingstone 1872g:[32]-[34]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. These pages provide a list of Livingstone's carriers and describe the items that each individual was responsible for transporting. Without such diaries, the names and roles of these individuals would be lost to history. |

This list not only presents previously hidden information, but opens new areas for research on the expeditionary group. The recovered information points to the transnational make-up of expeditions and gives rise to new questions about the reasons behind why people joined them. In this vital but previously unused or ignored information is data vital to understanding the engagement between British exploratory expeditions and the people who worked with and for such parties in nineteenth-century central Africa.

By presenting the “raw” information provided in Livingstone’s manuscripts, notebooks, field diaries and letters – although partial and unsubstantiated – Livingstone Online builds on “the potential of archival investigation within metropolitan (i.e. European or North American) collections to yield evidence that might challenge the ‘heroic’ view of exploration” (Driver 2013:422). The fifty-three porters on Livingstone’s list help users to create a conceptual understanding of the structure of such an expedition. The digital library also negates the limitations created by the lack of an index to the Last Journals or by having to access physical archives which hold information pertaining to this period of Livingstone’s travels.

Painted Lantern Slide of Susi and Chuma, Date Unknown (after 1873). Copyright The Centre for the Study of World Christianity, University of Edinburgh. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. Other contemporaneous images of Susi and Chuma present them dressed in western-style clothing. This image, in turn, speaks to one strategy by which African exploration could be staged in Britain to promote stereotypical views of non-western populations and locations.

Moreover, it is possible to use the information in these pages and in other such instances to find further “unused” information. Having established who the porters were, users can then search through Livingstone Online’s digital catalogue to find out more about these people. Of those who were portering, for instance, Mabruki and Gardner turn up in an earlier field diary alongside five other people in what appears to be a list in which Livingstone is recording the paying of wages (Field Diary XIV, 0104, 0105, 0106).

Specifically, the entry for 20 February 1872 records the fact that Livingstone paid seven of the people working with him roughly 40 yards of white cloth each (field Diary XIV, 0105). Such a large wage suggests the value that Livingstone placed on these people and their importance to his expeditionary group.

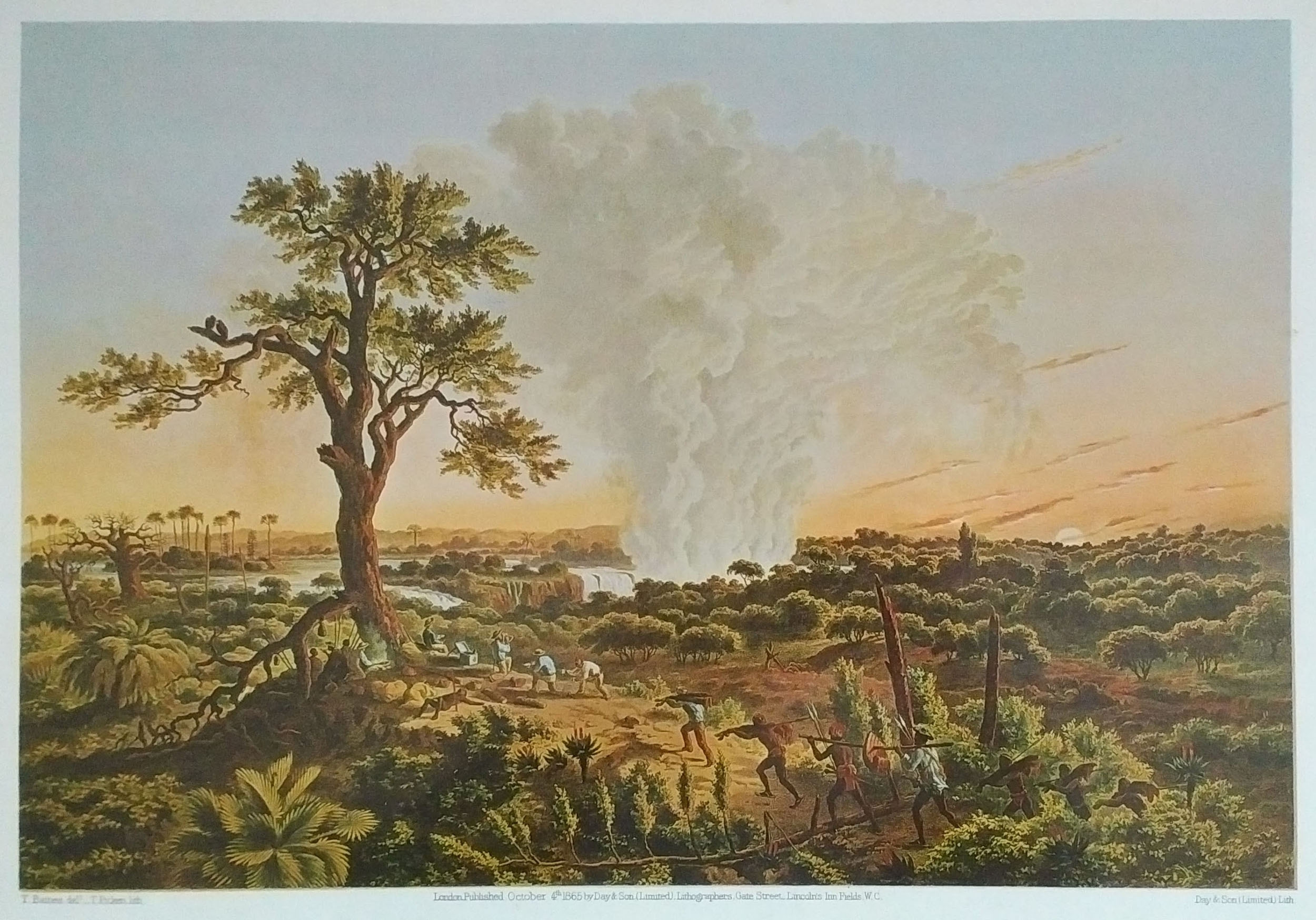

Image of Thomas Baines, The falls by sunrise, with the 'spray cloud' rising 1,2000 feet, c.1865. Copyright Kate Simpson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. Baines accompanied Livingstone for part of the Zambezi Expedition (1858-64). Paintings such as this offer an indication of the many forms that narratives of exploration could take beyond the written record.

Only two of these people, Susi and Chuma, have been memorialised in historical chronicles in any substantial manner. The passage from the field diary, however, raises the question of why the other members of the party have not been not recognised in a similar manner. It could be suggested that their stories have been lost from the expeditionary narrative because they did not travel to Britain (and so, for instance, assist Horace Waller in editing the Last Journals for publication).

Whatever the case, the digital library with its remediated materials and enhanced methods of data searching, facilitates the excavation and recovery of those who have been written out of history. Livingstone Online’s users can thus move beyond un-individualised representations of a homogenous group known as porters (cf. Waller, in Livingstone 1874:345), to instead disclose and identify these individuals and their specific roles in the socio-cultural network of the expeditionary group.

Envelope used to hold Saleh bin Osman and Edward J. Glave, Testimony, 12 November 1890. Copyright Smithsonian Libraries, Washington, D.C. Osman traveled with Henry M. Staley on the ill-fated Emin Pasha Relief Expedition (1886-89). Osman's narrative, which he dictated to Glave, offers a non-western perspective on some of the most controversial events of the expedition. Part of Livingstone Online's work centers on recovering and publishing narratives such as this one.

By bringing the people involved in such interactions to the fore, Livingstone Online allows users to recover multiple narratives and histories from the predominant account crafted by Livingstone and his publishing editors. It is in the very specific site and moment of the colonial cultural encounter – traced through the documents in which Livingstone recorded his immediate reactions and which are now published by Livingstone Online – that new understandings of interactions across cultures surrounding exploration can begin to emerge.

Conclusion Top ⤴

Livingstone Online, as a digital library, can provide a unique insight into British expeditionary groups in nineteenth-century Africa. The user can access multiple strands of information across multiple formats to see the lived life of an expedition. It is the way a digital library like Livingstone Online encourages immersion in primary records and allows users to make connections across those records that drives alternative ways to engage with nineteenth-century cultural exchange in Africa.

Mussell notes that “if we want to produce new knowledges, new ways of understanding the period and its people, then we have to allow digitized objects to behave in new ways” (2014:383). The digital library allows the user to “read” the objects in the library in innovative ways, to search for new patterns, and to explore digitally physical items held in multiple countries all from a single screen. The extent of the materials in the digital library ensures that it will remain a driving force in critical rewriting of the persistent and reductive European narratives of nineteenth-century African exploration.

The digitisation of Victorian documents about Livingstone’s expeditions in Africa allows for a new exploration of imperial histories and facilitates the decentring of singular European-focused expeditionary accounts. Livingstone Online uses Livingstone’s manuscripts as a point from which to engage afresh with an important period of intercultural encounter. As a digital library, the site shows how Livingstone was part of a much larger and more ambiguous cultural moment, involving multiple people with various agencies and differing motivations. In assessing and engaging with manuscripts, journals, diaries, letters, and notebooks, users can find the unknown hidden in the known.

Works Cited Top ⤴

Battles, Matthew. 2013. “Specimens: Figurines, Fishers, Bugs and Bats – How things in the World Became Sacred Objects in a Museum.” Aeon Magazine, 30 Apr.

Bridges, Roy C. 1987. “Nineteenth-Century East African Travel Records with an Appendix on ‘Armchair Geographers’ and Cartography.” Paideuma 33: 179-96.

Bridges, Roy C. 1998. “Explorers’ Texts and the Problem of Reactions by Non-Literate Peoples: Some Nineteenth-Century East African Examples.” Studies in Travel Writing 2: 65-84.

Driver, Felix. 2013. “Hidden Histories Made Visible? Reflections on a Geographical Exhibition.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 3: 420-35.

Helly, Dorothy O. 1987. Livingstone’s Legacy: Horace Waller and Victorian Mythmaking. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press.

Kennedy, Dane. 2014. “Introduction: Reinterpreting Exploration.” In Reinterpreting Exploration: The West in the World, edited by Dane Kennedy, 1-17. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Livingstone, David. 1857a. Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa. London: John Murray.

Livingstone, David. 1857b. Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa (Part I). Jan.-Oct. 1857. MS. 42428. National Library of Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1865. Field Diary I. 4 Aug. 1865-31 Mar. 1866. 1123. David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1872h. Field Diary XVI. 1 Dec. 1872-6 Apr. 1873. 1132. David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1874. The Last Journals of David Livingstone in Central Africa, from 1865 to his Death, edited by Horace Waller. 2 vols. London: John Murray.

Livingstone, Justin D., 2014. Livingstone’s Lives. A Metabiography of Victorian Icon. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

MacKenzie, John M. 2013. “David Livingstone – Prophet or Patron Saint of Imperialism in Africa: Myths and Misconceptions.” Scottish Geographical Journal 129 (3-4): 277-91.

Mandala, Elias. 2014. "The Making of Wage Laborers in Nineteenth Century Southern Africa: Magololo Porters and David Livingstone, 1853-1861." International Labor and Working-Class History 86: 15-35.

Mussell, James. 2014. “The Postcolonial Archive.” Journal of Victorian Culture 19: 383-84.

Wisnicki, Adrian S. 2010. "Rewriting Agency: Baker, Bunyoro-Kitara, and the Egyptian Slave Trade." Studies in Travel Writing 14 (1): 1-27.

![A page from David Livingstone, Field Diary XVI (1872h:[163]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, University of Glasgow Photographic Unit, and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). A page from David Livingstone, Field Diary XVI (1872h:[163]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, University of Glasgow Photographic Unit, and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/about-this-site/reading-exploration-through-the-digital-library/liv_000016_0163-article.jpg)

![A page from David Livingstone, Field Diary XVI (1872h:[162]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, University of Glasgow Photographic Unit, and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). A page from David Livingstone, Field Diary XVI (1872h:[162]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, University of Glasgow Photographic Unit, and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/about-this-site/reading-exploration-through-the-digital-library/liv_000016_0162-article.jpg)

![Image of a page of David Livingstone, Field Diary VI (1866e:[36]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, University of Glasgow Photographic Unit, and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). Image of a page of David Livingstone, Field Diary VI (1866e:[36]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, University of Glasgow Photographic Unit, and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/about-this-site/reading-exploration-through-the-digital-library/liv_000006_0036-article.jpg)

![Image of a page of David Livingstone, Field Diary V (1866d:[77]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, University of Glasgow Photographic Unit, and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). Image of a page of David Livingstone, Field Diary V (1866d:[77]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, University of Glasgow Photographic Unit, and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/about-this-site/reading-exploration-through-the-digital-library/liv_000005_0077-article.jpg)

![An image of a page of Field Diary XV (Livingstone 1872g:[32]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of Field Diary XV (Livingstone 1872g:[32]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/about-this-site/reading-exploration-through-the-digital-library/liv_000015_0032-article.jpg)

![An image of a page of Field Diary XV (Livingstone 1872g:[33]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of Field Diary XV (Livingstone 1872g:[33]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/about-this-site/reading-exploration-through-the-digital-library/liv_000015_0033-article.jpg)

![An image of a page of Field Diary XV (Livingstone 1872g:[34]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of Field Diary XV (Livingstone 1872g:[34]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/about-this-site/reading-exploration-through-the-digital-library/liv_000015_0034-article.jpg)