Conservation and Transport

Cite page (MLA): Wisnicki, Adrian S., and Heather F. Ball. "Conservation and Transport." In Livingstone's Letter from Bambarre. Adrian S. Wisnicki, dir. Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. University of Maryland Libraries, 2017. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/9d934abd-24be-4b78-bd98-8b5a4ae956e0.

This page outlines the conservation steps taken to stabilize the manuscript of Livingstone's Letter from Bambarre, then summarizes the circumstances surrounding the transportation of the letter for spectral imaging from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City to the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore.

Yana Van Dyke, a paper conservator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, carried out the conservation of Livingstone’s letter and prepared the letter for transport from the Met to the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore. The letter required conservation because pieces of the letter were detached, torn, or folded over. These issues arose partly from the adverse environmental circumstances in which the letter was originally written and transported, and partly from the fact that Livingstone wrote the letter with iron gall ink, which can contain a corrosive metallic component and thus deteriorate the paper upon which it is used.

Yana Van Dyke prepares the letter for imaging. Copyright Adrian S. Wisnicki. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported

In performing her work, Van Dyke first removed the letter from its original frame, which consisted of a double-sided tongue and groove frame assembly, and which presented the letter between two pieces of glass. She then placed individual sheets onto a working light box, and during a period of approximately two days, repaired detached portions of the letter and reinforced breaks along the edges with a toned tenjugo Japanese paper and a thermoset (gently heat-activated) adhesive, which, unlike aqueous adhesives, will not accelerate the deterioration mechanism of iron gall ink.

Alongside this work, Van Dyke also gently humidified and opened up folds, creases, and flaps, thereby revealing previously hidden portions of the writing.

Yana Van Dyke prepares the letter for imaging. Copyright Adrian S. Wisnicki. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported

The last phase of the treatment involved overall humidification and flattening of the letter through a Gore-Tex humidification package. The letter was then placed between acid-free lens tissue and blotters and was allowed to dry under weight for ten days.

For transportation, Van Dyke secured the letter with conservationally sound, museum-quality materials. She photo-cornered the actual pages of the letter into a non-buffered high alpha cellulose paper folder, which itself was placed into a black matboard folder. The package was then surrounded with coroplast so as to create a rigid exterior layer, which in turn was wrapped in plastic in order to secure the letter from hazards such as rain or snow.

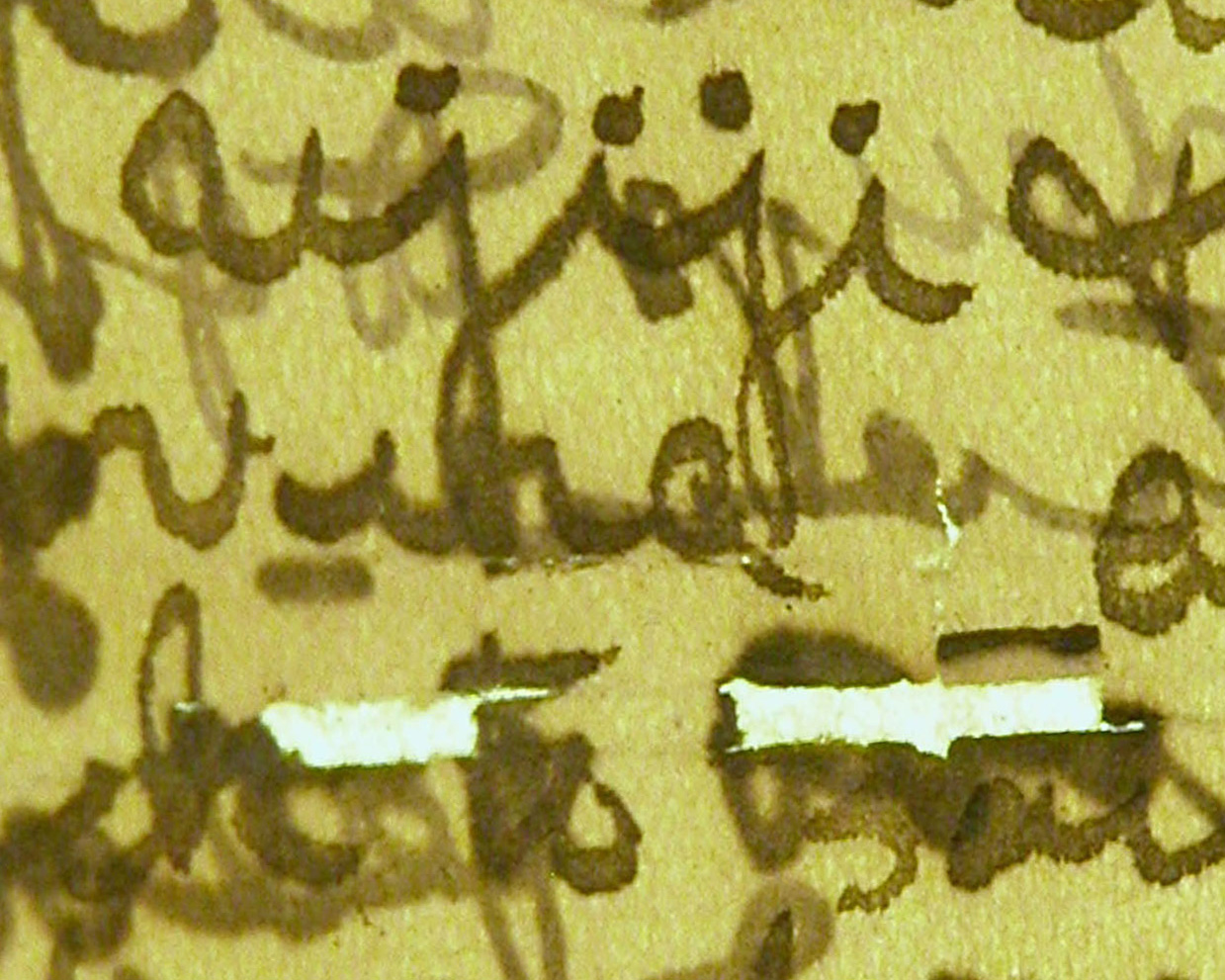

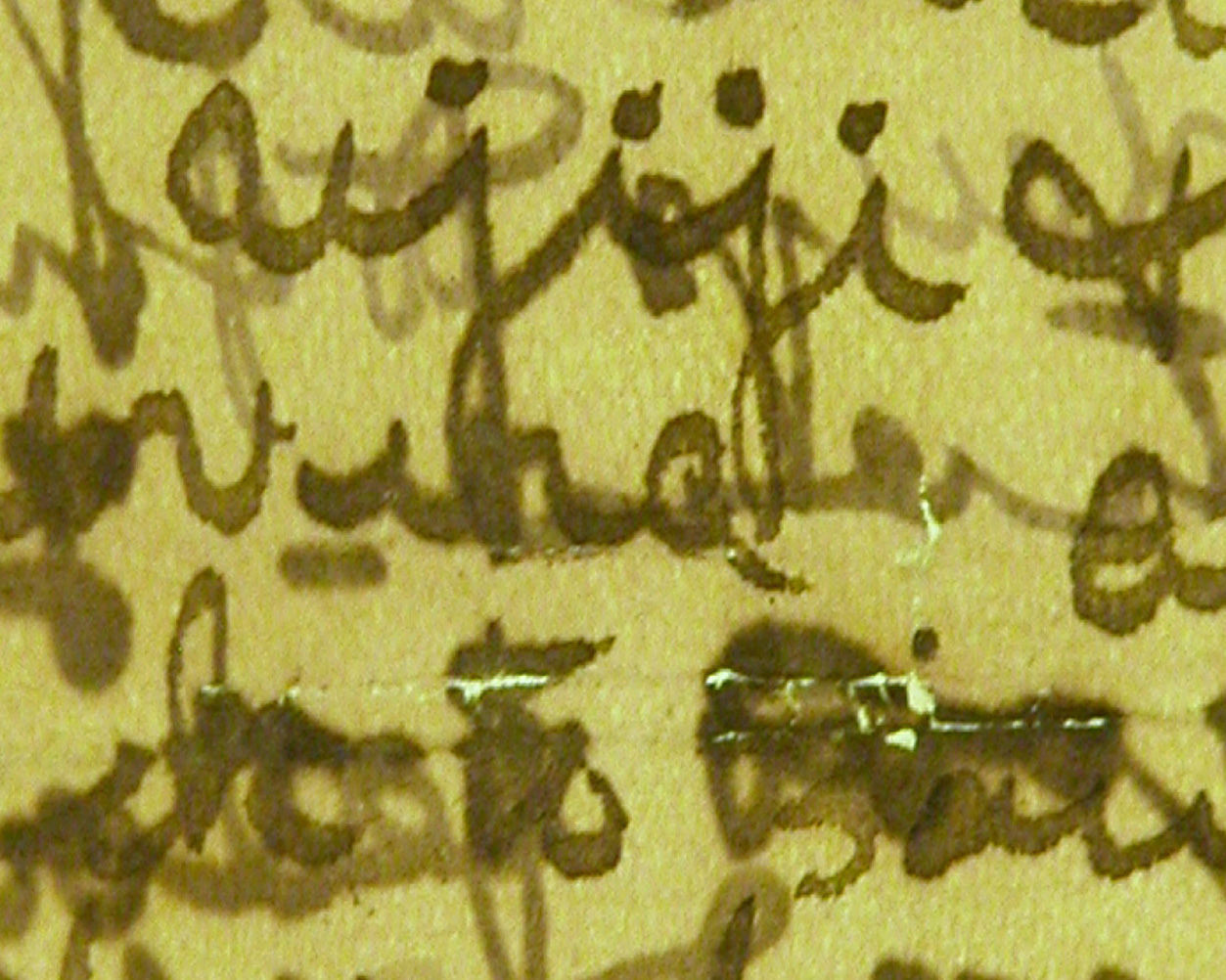

| (Left; top in mobile) A portion of the Letter from Bambarre before conservation. Copyright Peter and Nejma Beard. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. (Right; bottom) A portion of the Letter from Bambarre after conservation. Copyright Peter and Nejma Beard. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. |

The letter was therefore ready for delivery on 26 February 2010, the date slated for the spectral imaging. Yet that morning the transport team awoke to discover that a massive snowstorm had arrived and that the northeastern United States was blanketed in snow.

The letter was ready, but the team deemed it in no one’s interest to test the survival capabilities of the letter one more time. As a result, the imaging was rescheduled, and Adrian S. Wisnicki (project director), Jeff Drouin (technological assistant), and Heather F. Ball (research assistant) finally transported the letter to Baltimore and back on 4 March 2010.

The snowstorm of 26 February 2010, as seen near Project Director Adrian S. Wisnicki’s home in Brooklyn. Copyright Adrian S. Wisnicki. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported

After imaging, the letter was returned to New York and placed back in its original frame, although the old glass was replaced with Tru Vue Museum Glass, which has an anti-reflective coating and provides 99% protection against UV light.

![Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_013723_0001-new-carousel_0.jpg)

![Processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's "Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal" (Livingstone 1870a:[3] pseudo_v4_BY), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's "Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal" (Livingstone 1870a:[3] pseudo_v4_BY), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000211_0003_pseudoBY_940_by_592-carousel.jpg)

![David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, [1869], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland: CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, [1869], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland: CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_003006_0001-new-carousel_0.jpg)