Critical Reflections on the Manuscripts (1)

Cite page (MLA): McDonald, Jared. "Critical Reflections on the Manuscripts (1)." Mary Borgo Ton, ed.; Adrian S. Wisnicki, ed. and illus. In Livingstone’s Manuscripts in South Africa (1843-1872). Jared McDonald and Adrian S. Wisnicki, dirs. Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. University of Maryland Libraries, 2018. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/2141a7e1-cb90-4969-a709-608a1c787ace.

This page, the first part of a two-part essay, presents critical reflections on the contents of the letters contained in the present edition of Livingstone’s manuscripts in South Africa (1843-72). The essay explores several themes and topics that emerge from a close reading of the letters together. These themes and topics include Livingstone’s global correspondence network, his views on mission, his representations of African peoples, his reflections on phrenology and scientific racism, and his penchant for wit and humour. Critical reading of the letters published through the present collection offers fresh perspectives on Livingstone, but also valuable information on his contexts and the peoples he encountered. Read the second part of the essay here.

Introduction Top ⤴

This essay provides critical reflections on the contents of the letters contained in the present edition of Livingstone’s manuscripts in South Africa (1843-72). The following discussion is arranged thematically, while also exploring the chronological and geographical contexts of the letters, all of which have been collected from archives, libraries and museums in South Africa.

| (Left; top in mobile) Image of a page of David Livingstone, Letter to Robert N. Hayward, 17 July 1843: [7]. (Right; bottom) Image of a page of David Livingstone, Letter to John C.L. Marsh, 21 November 1872: [1]. Images copyright The Brenthurst Press (Pty) Ltd, 2014. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. These images are drawn from, respectively, one of the earliest letters in the present edition and the latest dated letter. |

In terms of timeline, the original letters included in the edition span Livingstone’s career as a missionary and missionary-explorer, from the beginnings of his time in Africa in the early 1840s to the last years of his life in the early 1870s. The first letters date back to 1843, two years after Livingstone’s arrival in southern Africa. The last dated letter in the collection was written in November 1872, with Livingstone noting his location as “South Central Africa.” This was a year after the meeting with Henry Morton Stanley at Ujiji and six months before his death, near Chitambo, in modern Zambia.

The 30 year period covered by the letters in this collection affords the opportunity to interrogate Livingstone across time. The essay develops a critical reading of Livingstone’s representations of different peoples, places, and themes across the extent of his career in Africa. This approach provides fresh insight into Livingstone’s ideas and thoughts on a variety of themes and topics and shows how his opinions evolved and transitioned over this period. Livingstone’s observations are also an important historical source on Africa during the mid to late nineteenth century, as these letters show.

![Image of David Livingstone, Map of Central Africa from Kuanabare River, Angola to Tete, Mosambique, [1855-1856?], detail: [1]. Copyright National Library of South Africa, Cape Town Campus. Used by permission. Image of David Livingstone, Map of Central Africa from Kuanabare River, Angola to Tete, Mosambique, [1855-1856?], detail: [1]. Copyright National Library of South Africa, Cape Town Campus. Used by permission](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/critical-reflections-the-manuscripts-1/liv_000047_0001-article-1200.jpg)

Image of David Livingstone, Map of Central Africa from Kuanabare River, Angola to Tete, Mosambique, [1855-1856?], detail: [1]. Copyright National Library of South Africa, Cape Town Campus. Used by permission. This is the only map included in the present edition. The segment shown here underscores Livingstone's focus on mapping rivers and their affluents and on outlining the geographical extent of the settlements of specific African ethnic groups.

The essay continues with a discussion of the geographical scope of the letters with particular attention given to their places of composition. This is followed by an appraisal of the sorts of recipients who received these letters. Attention to the places of composition and recipients sheds lights on Livingstone’s global correspondence network and allows us to assess how his writings differed in tone, content, and pitch in relation to where he was and to whom he was writing.

Thereafter, the essay reflects critically upon other themes which come to light by a close reading of the letters, including Livingstone’s opinions of African traditional medicine, his thoughts on the growing influence of phrenology and scientific racism, and his concerns over his own legacy. The essay ends with a look at some instances of wit and humor in the letters; these reveal a side of Livingstone at odds with most critical discussions of his character.

Places of Composition Top ⤴

The critical edition of Livingstone’s manuscripts in South Africa (1843-72) may represent a relatively small sample of Livingstone’s writings, but, as noted, the collection covers a timeline of over 30 years. The letters also encompass the geographical extent of Livingstone’s travels and explorations during this period and as such, offer a valuable lens through which to assess his thoughts, opinions, and observations over time and in different cultural contexts.

The collection includes letters composed in places such as Kuruman, Mabotsa, and Kolobeng in the northern Cape of modern South Africa, during a time when Livingstone more or less conformed to life as a missionary in the services of the London Missionary Society. Other places of composition include Nyungwe, Tete, and Quelimane, where Livingstone ventured on his first and second expeditions, as well as London and Manchester, where he stayed in 1856-57 during his first visit to Britain since departing for southern Africa in 1841.

| (Left; top in mobile) 'View of Kuruman.' Image from Lantern Slides of the Life, Adventures, and Work of David Livingstone, Date Unknown: [5]. (Right; bottom) 'Thrown from an Ox.' Image from Lantern Slides of the Life, Adventures, and Work of David Livingstone, Date Unknown: [17]. Images courtesy of the Smithsonian Libraries, Washington, D.C. |

Livingstone composed other items in this collection while on the move, writing from places such as the steamship Pearl, which took Livingstone back to Africa in 1858. There are also letters written aboard the Ma-Robert, named in recognition of the Makololo name for Livingstone’s wife Mary, as well as letters written while steaming along or camping besides the Zambezi and Shire Rivers or Murchison’s Cataracts. Such sites of composition underscore the modes of transport Livingstone employed during his expeditions as well as his commitment to writing, even when not stationary.

There are also several items written during stops along his voyage home after the ill-fated Zambezi Expedition, including at Zanzibar and Bombay. The last dated letter in the collection was written in “South Central Africa,” which suggests that Livingstone was not sure of his exact location at the time of writing or, again, was moving between locations (Livingstone 1872a). Interestingly, this letter was penned at a time when Livingstone was considered lost, or dead, by many who had followed his travels and were interested in his fate.

Recipients and Social Networks Top ⤴

The variety of recipients for items in the present collection reveals the extent of Livingstone’s social networks. Even a relatively small sample, such as the present one, highlights how well-connected Livingstone became in the aftermath of his celebrated transcontinental crossing of 1852-56. Several letters are directed to high profile individuals, thereby illuminating the social clout Livingstone enjoyed, at least before the controversial Zambezi Expedition.

One such prominent recipient in the collection is the Earl of Clarendon, one-time Foreign Secretary of Britain. In his correspondence with the Earl, Livingstone reflects on his time as a missionary in Africa, noting that were it not for “the efforts of England,” Africa would have “been inaccessible to the gospel” (Livingstone 1863a:[3]). As discussed below, Livingstone was feeling particularly frustrated with the Portuguese presence in southern Africa at the time he wrote this letter. This may explain why his comments to the Earl have a nationalist tone, emphasizing what Livingstone regards as Britain’s laudable role as a global leader in the mission enterprise.

![Image of a page from Scenes in Hot Latitudes and Travels in Search of the Wishi Washi to its Junction with the Puddi Muddi, Date Unknown: [32]. Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Libraries, Washington, D.C. Image of a page from Scenes in Hot Latitudes and Travels in Search of the Wishi Washi to its Junction with the Puddi Muddi, Date Unknown: [32]. Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Libraries, Washington, D.C](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/critical-reflections-the-manuscripts-1/liv_012015_0032-article-1200.jpg)

Image of a page from Scenes in Hot Latitudes and Travels in Search of the Wishi Washi to its Junction with the Puddi Muddi, Date Unknown: [32]. Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Libraries, Washington, D.C. This illustration parodies the patriotic dimension of Livingstone's famous encounter with Henry M. Stanley, the individual whom James Gordon Bennett sent to find Livingstone in central Africa. The typewritten caption for the image reads: "The Doctor having waited in vain for the promised supplies from the Royal Geographical Society is suddenly & unexpectedly cheered by the welcome sounds of Hail Columbia & the 'Bird of Freedom' soaring on it's [sic] outstretched wings, New England's pride with help & succor & the Star Spangled Banner."

Another of the letters in the collection is a lengthy account written to James Gordon Bennett, owner and editor of the New York Herald, the newspaper which despatched Henry Morton Stanley to Africa to find Livingstone. Detailed, but also rambling, the letter is partly a thank-you note in acknowledgement of Bennett’s interest in Livingstone’s life and travels, and partly an illuminating glimpse into Livingstone’s thoughts about Africa and Africans towards the end of his life. As discussed below, in this letter Livingstone drifts away from the typical, disparaging views of Africans and African knowledge systems characteristic of this period.

In one of the earlier letters in the collection, Livingstone writes to the Reverend Andrew Murray, resident minister at Graaff-Reinet, an important frontier town in the Cape Colony. Murray once hosted Livingstone at his home in Graaff-Reinet. Unlike Livingstone, Murray enjoyed cordial relations with the Boers. Written at Kuruman in June 1847, Livingstone’s letter to Murray notes that he, Livingstone, is visiting the mission of his father-in-law, Robert Moffat, in order to attend a missionary committee meeting.

While this is the main reason for the visit, Livingstone conveys that the “chief object” of the concurrent visit of Livingstone’s wife, Mary, appears to be “to add another unit to the population of this planet” (Livingstone 1847a:[1]). In doing so, Livingstone reveals the news that he and Mary are expecting. In addition to the quirky tone of the announcement, the letter is also tinged with what appears to be a slight sense of disapproval. Livingstone clearly feels comfortable enough in his friendship with Murray to convey the news of his wife’s pregnancy in such a whimsical manner.

![Image of a page from David Livingstone, Letter to Mary Livingstone, 28 May 1852: [4]. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, University of Glasgow Photographic Unit, and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). Image of a page from David Livingstone, Letter to Mary Livingstone, 28 May 1852: [4]. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, University of Glasgow Photographic Unit, and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/critical-reflections-the-manuscripts-1/liv_000758_0004-article-1200.jpg)

Image of a page from David Livingstone, Letter to Mary Livingstone, 28 May 1852: [4]. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, University of Glasgow Photographic Unit, and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The closing of this letter, cited partly below, expresses Livingstone's affection for his wife Mary Livingstone and concern for his children.

Only one of the letters in the collection is addressed to Mary Livingstone. Written shortly after Mary’s departure with the Livingstone children from Cape Town in 1852, the letter is loving, but hardly reassuring, as most of the text concerns developments in Cape Town and Livingstone’s preparations for his journey north to Kuruman and beyond.

Yet the letter reveals a more paternal side to Livingstone via his note that he has included “three little letters for the children” (Livingstone 1852a:[2]) as well as other humanizing elements. For instance, Livingstone also asks Mary to “[g]ive each of the children my love and a kiss for me, tell them I love them still though they are far from me, and though I have parted with them I still love them and will pray for them, but they must pray for themselves and for me” (1852a:[3]). In a clear demonstration of affection for Mary, the letter ends with Livingstone writing: “Farewell my dearest my own sweet love. When shall I see you again [?]” (1852a:[4]).

![Image of a page from a promotional booklet for Livingstone: A Drama of Reality (Film), 1925, detail: [3]. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/). Image of a page from a promotional booklet for Livingstone: A Drama of Reality (Film), 1925, detail: [3]. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/critical-reflections-the-manuscripts-1/liv_014024_0003-article-1200.jpg)

Image of a page from a promotional booklet for Livingstone: A Drama of Reality, 1925, detail: [3]. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland

In addition to drawing attention to the types of social networks Livingstone belonged to and relied upon, often from a distance, the varied recipients of the letters contained in this collection point towards Livingstone’s different writing styles. To give one example, the formal, nationalist tone of letters written to high ranking public figures such as the Earl of Clarendon contrasts with the playful tenor of letters addressed to close friends and confidants.

Such differences foreground Livingstone’s tendency to edit the content and pitch of his letters depending upon the relationship he held with the intended recipients. When read together, the letters indicate that Livingstone carefully shaped his writing to reflect the audience. In doing so, he made deliberate choices in terms of subject-matter and delivery that depended on the given recipient.

The Demands of Missionary Work Top ⤴

One subject to which Livingstone dedicated much thought and reflection in the letters in the present edition concerns the demands of being a missionary; at least a missionary in the mould of which he approved. He also reflected on the extent to which he lived up to his own ideals on the matter.

Livingstone makes it clear in several of these letters that a missionary in Africa needed to be resourceful, while also requiring fortitude in the face of many challenges. The task of spreading the gospel met numerous obstacles and, in order to overcome these, a missionary has to be prepared to be “a jack of all trades,” Livingstone writes (1847a:[7]).

| (Left; top in mobile) Wooden Box with Inset Cross, Made with Wood from Mary Livingstone's Grave, [After 1862]. Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Object images used by permission. May not be reproduced without the express written consent of the National Trust for Scotland, on behalf of the Scottish National Memorial to David Livingstone Trust. (Right; bottom) Commemorative Cross in Presentation Box, Made from the Wood of the Mvula Tree under which David Livingstone's Heart was Buried after his Death in May 1873, [c.1900]. Images copyright National Museums Scotland. Used by permission. Any form of reproduction, transmission, performance, display, rental, lending, or storage in any retrieval system without the written consent of the copyright holders is prohibited. These items mark key milestones in Livingstone’s life, namely the death of his wife in 1862 and Livingstone’s own in 1873. The materiality of the items, in turn, alludes to Jesus’s profession as a carpenter, an area in which Livingstone himself felt that missionaries should be skilled. |

These letters show that Livingstone clearly revelled in the status his qualification as a medical doctor gave him as well as the relative power and influence this afforded him among the many peoples he encountered during his travels. Livingstone indicates that the letter written to Andrew Murray (in which he announces the news of Mary’s pregnancy, see above), has been penned “after forging a set of harrow teeth out of an old waggon wheel band” (Livingstone 1847a:[7]). Livingstone goes on to state that the feat was “fine doctoring,” and that he has to keep his fingers “nimble enough to cut a tumour […] out of a woman’s back” should the need arise (1847a:[7]).

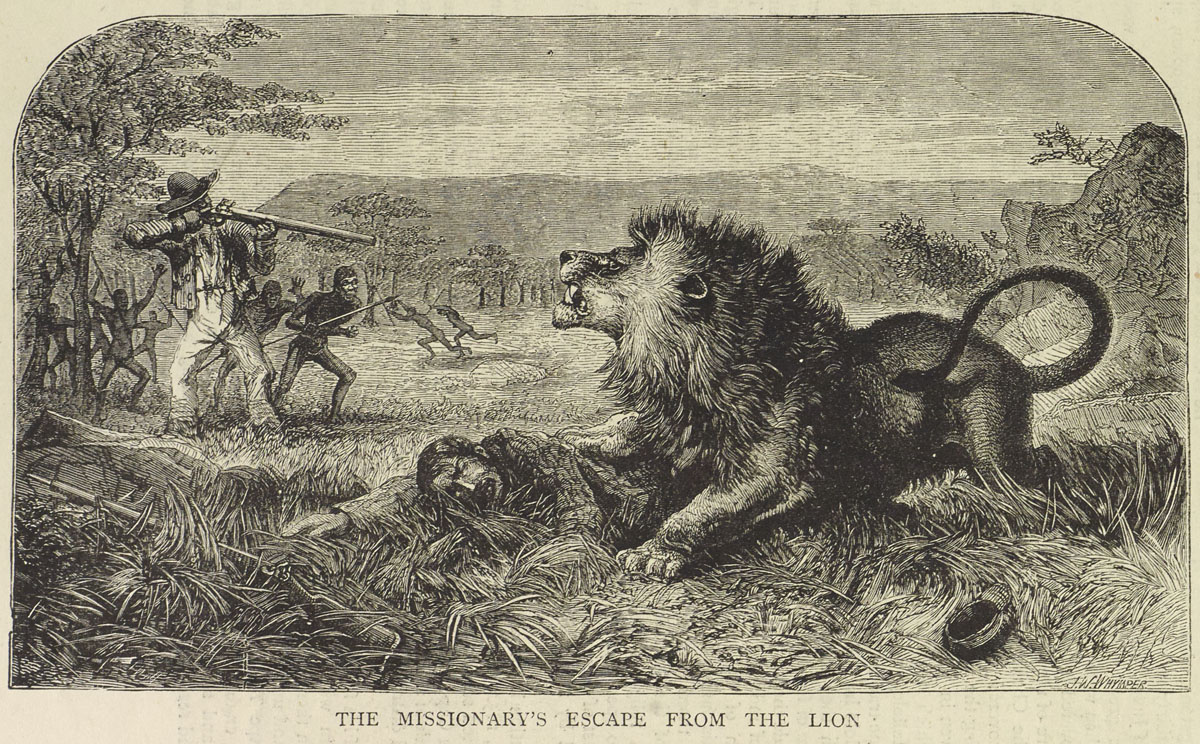

The letters in this collection also indicate that for much of his career, Livingstone held the opinion that effective missionaries, who went “to the actual heathen,” needed to be “carpenters, smiths, gardeners, schoolmasters, ministers, often doctors and sometimes male midwives too” (Livingstone 1856f:[2]. In other words, such missionaries needed a variety of skills. Physical prowess was also essential. In recounting his mauling by a lion, Livingstone notes that while several other members of the party who had also been injured in the attack were carried back to camp, he himself “walked home without assistance” (Livingstone 1845:[3]).

'The Missionary's Escape from the Lion.' Illustration from 'The Life and Labours of David Livingstone,' The Graphic, 25 April 1874: 397. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. This illustration also appears in Livingstone's first published book, Missionary Travels (1857). The wording of the original caption, shown here, draws attention to the religious dimension of this incident.

Given the importance he attached to such masculine qualities, it is not surprising that Livingstone was quick to praise his own fortitude while pointing out perceived weaknesses in others, especially missionaries. Perhaps in a bid to deflect some of the fault for the failures of the Universities Mission, Livingstone suggests that the difficulties the Mission encountered ought to have been expected, especially as the people for whom the mission was intended are “entirely ignorant” and “a little more formidable than those of the Makololo country” (Livingstone 1860c:[2]).

As far as Livingstone is concerned, if the University men lack the “pluck and desire to go beyond other men’s line of things made ready to their hands” then they are “not the stuff [he] thought them made of” (Livingstone 1860c:[2]). Livingstone implies that the mission project has suffered as a consequence of such feeble and unsuited missionaries being despatched to the mission field.

Views on Mission Top ⤴

It is apparent from these letters that Livingstone’s views on the mission enterprise began to shift early on in his career. The letters show that initially Livingstone was heavily influenced by his father-in-law, Robert Moffat, who was disdainful towards John Philip, the director of the London Missionary Society in the Cape Colony, particularly of the latter’s efforts to train “native converts” to spread the gospel.

We know from related scholarship that upon his arrival in Cape Town in March 1841, Livingstone stayed with John Philip and his wife, Jane, for a month before departing for Kuruman. During this time, Livingstone came to regard the Philips in a favorable light. In particular, Livingstone appears to have been persuaded by the merits of John Philip’s efforts to improve conditions for the Colony’s indigenous inhabitants.

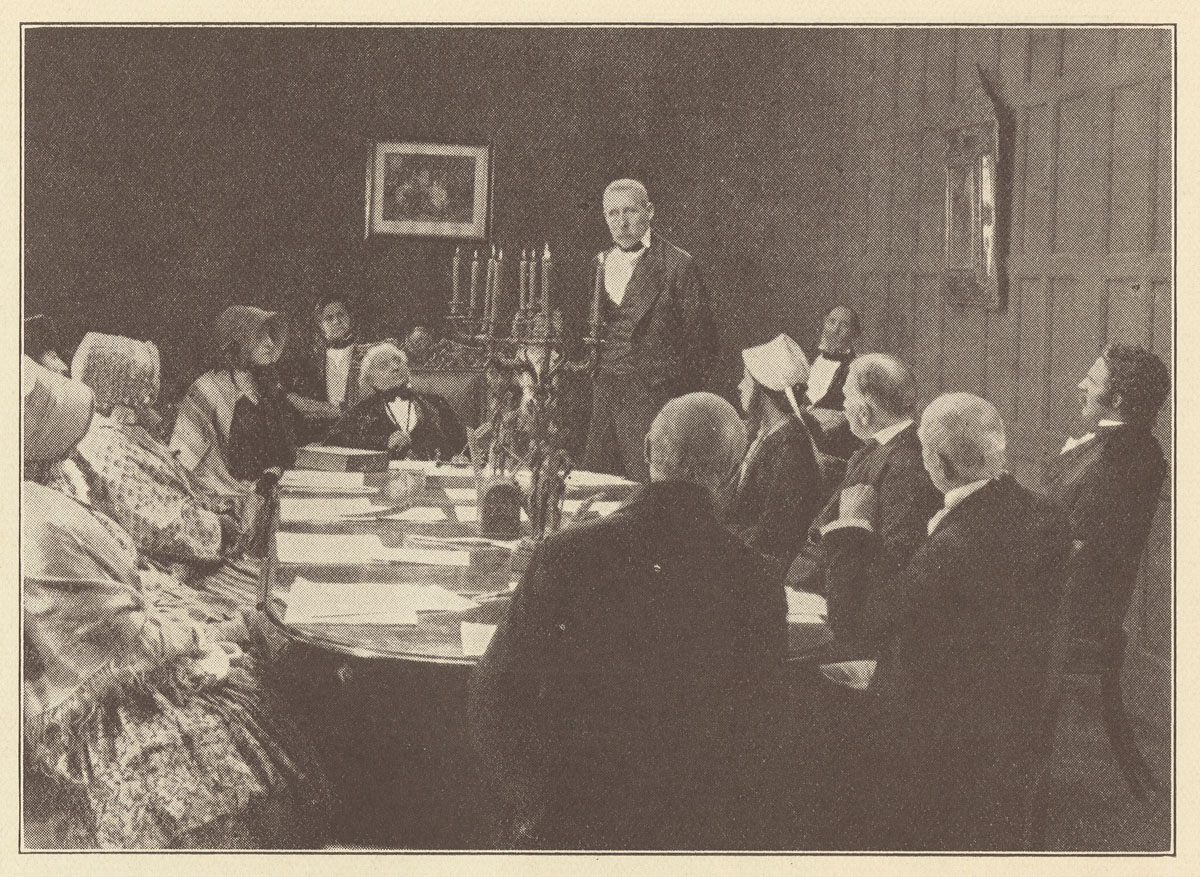

'Livingstone hears Robert Moffat address the London Missionary Society—and responds to The Call!' Photograph from promotional booklet for Livingstone: A Drama of Reality, 1925. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. Moffat is standing, while Livingstone appears seated at far right. The letters in the present edition reveal nuances in Livingstone's views on missionary work that are missing from popular representations such as this one.

In this respect, Philip appears to have had a stronger influence than Moffat over Livingstone when it came to his opinions on the Colony’s treatment of its indigenous inhabitants and neighbours, especially the amaXhosa (also Xhosa) on the eastern frontier. In keeping with Philip’s more radical, liberal political views, Livingstone publically supported the amaXhosa in Mlanjeni’s War, or the Eighth Frontier War, which erupted on the eastern frontier in 1851.

For Livingstone, the amaXhosa were rightfully defending their homeland from encroachments by British and Boer settlers. In time, however, this view became more nuanced as Livingstone would come to encounter obstacles to his own ambitious plans to spread Christianity, commerce, and civilization further north. Rather than being opposed to British imperialism, Livingstone objected to unfettered settler colonialism.

Beyond the influence of Philip, these letters reveal that Livingstone also valued independent thought in regard to his general interactions with Africans. During the early years of his personal mission in and beyond the northern Cape, it appears that Livingstone preferred to depend on his own observations rather than those of others.

Image of John Arrowsmith, Map of South Africa Showing the Routes of Revd Dr Livingstone Between the Years 1849 & 1856, 1857, detail. Courtesy of Internet Archive. The red line traces Livingstone's travels among the lands of the "Bichuanas" (Sotho-Tswana).

For example, in a letter of February 1843, Livingstone expresses his doubts over the manner in which the Sotho-Tswana (also Bechuanas) have been represented in Britain. In one case, Livingstone notes having heard Robert Moffat declare that the Sotho-Tswana had had “no conscience until it was formed by the missionaries” (Livingstone 1843a:[2]). Initially, it emerges, Livingstone was under the impression that the description was “a poetical figure” meant to express the “wonderful creative powers” of the missionaries (1843a:[2]). However, in the particular letter, Livingstone writes that he has come to realize that Moffat’s claim was to be understood as “plain prose” (1843a:[3]).

Livingstone indicates that he has doubts that the people were “really so very far sunk” as had been portrayed (Livingstone 1843a:[2]). He also questions the legitimacy of the claim that the Sotho-Tswana have no concept of God. Recounting a “fable of the Chameleon and Dark Lizard,” Livingstone indicates that he is of the opinion that the Sotho-Tswana indeed hold beliefs about a supreme being and an afterlife (1843a:[3]).

It is perhaps not surprising that a few months later, in a letter of July 1843, Livingstone indicates that he has decided to “set off in order to obtain knowledge of the country and people” for himself (Livingstone 1843b:[1]). This letter, among others, indicates that by this time, Livingstone has become convinced that the only way to proselytize effectively among the Sotho-Tswana is to acquire a command of their languages, and that this could only be achieved through sustained contact.

![Image of two pages of David Livingstone, Letter to Robert Moffat 2, 13 August, September, 30 September 1847: [2]-[3]. Image copyright The Brenthurst Press (Pty) Ltd, 2014. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). Image of two pages of David Livingstone, Letter to Robert Moffat 2, 13 August, September, 30 September 1847: [2]-[3]. Image copyright The Brenthurst Press (Pty) Ltd, 2014. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/critical-reflections-the-manuscripts-1/liv_000640_0002-0003-article-1200.jpg)

Image of two pages of David Livingstone, Letter to Robert Moffat 2, 13 August, September, 30 September 1847: [2]-[3]. Image copyright The Brenthurst Press (Pty) Ltd, 2014. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. These pages contain many notes on seTswana, including vocabularies and a list of the letters of the alphabet "sufficient for writing all the dialects."

Livingstone’s rationale was not only guided by the need to be able to communicate, but by the need to convey Biblical imagery and idioms in a way that was culturally relevant and accessible in southern Africa. For instance, in a letter in which Livingstone presents a detailed phonetic table of seTswana, he also explains that it is of the “utmost importance to attain an idiomatic acquaintance with the channel through which we hope the strains of Divine mercy and consolation [would] flow to the benighted inhabitants” of the region (Livingstone 1847b:[1]).

In the same letter, Livingstone notes how certain individuals have acquired the language, but still use English idioms to convey messages when preaching. According to Livingstone, such idioms “could only be understood by natives who being accustomed to Europeans knew what was intended” (Livingstone 1847b:[1]). This is a remarkably progressive insight for the time.

Many of southern Africa’s languages had been ridiculed as backward and animal-like during the century and a half of colonial contact which had preceded Livingstone’s arrival in the region. For instance, Khoesan languages were mocked for their clicking sounds and were considered to be an indication of the so-called inferiority of the region’s indigenous inhabitants. Livingstone’s efforts to learn seTswana resulted in the publication of Analysis of the Language of the Bechuana in 1858, which was among the first linguistic studies to offer a model that was not based on classical grammar.

Representations of African Peoples Top ⤴

Livingstone’s observations on African languages and their value as a medium of Christianity, commerce, and civilization may have been insightful at times. Yet the letters published here also reveal contradictions and inconsistencies in the representations of the people groups Livingstone encountered. Such contradictions and inconsistencies emerge with regularity in the collection.

Though it is apparent from these letters that Livingstone questioned dominant, contemporary representations of African knowledge systems and languages, the present collection contains little by way of detailed observations of the people groups he encountered and among whom he sometimes spent extended periods of time. As a sample, these letters suggest Livingstone was not an observant or committed ethnographer. However, an examination of other Livingstone manuscripts (such as diaries or notebooks, all of which lie outside the scope of this edition) indicates that such limitations may be confined to letters.

| (Left; top in mobile) Image of a page of David Livingstone, Field Diary III, 14 May-30 June 1866: [37]. (Right; bottom) Image of a page of David Livingstone, Notebook, March 1866-March 1870: [43]. Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. These pages illustrate Livingstone's efforts as an ethnographer. The page from the diary includes notes on and illustrations of body markings made by the Makoa ethnic group. The page from the notebook sets out a "Fable African" collected from an unknown source. |

That said, Livingstone appears to have gained a greater appreciation for African traditions, medicine, and law towards the end of his life, as shown below. For much of his time in Africa Livingstone operated within an intellectual and spiritual paradigm that actively undermined and disregarded African cosmologies and bodies of knowledges. It is perhaps not surprising that so little of his writing in the letters in this edition was dedicated to describing cultural practices. It was sufficient for the recipients of his correspondence to know that Africans were in need of the gospel and European civilization.

Whenever observations of African peoples are included in these letters, they are often deployed in order to reconfirm this vision and so required little by way of detail or explanation. Indeed, in questioning why “fine looking men” such as the Manyema (also Manyuema) “should be so low in the moral scale,” Livingstone indicates that he believes it could be attributed to “the non introduction of that religion which makes those distinctions among men which phrenology and other ologies cannot explain – the religion of Christ […]” (Livingstone, 1872a:[37]).

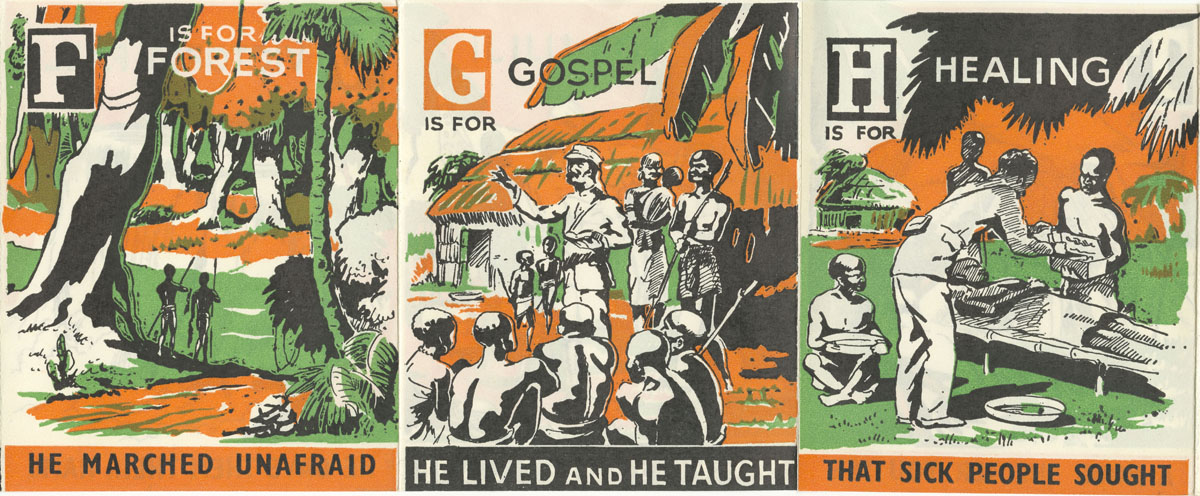

Image of S.E. Iredale, Alphabetical Adventures of Livingstone in Africa for Boys and Girls (The Livingstone Press, London), 1941, detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. These images use the story of Livingstone to play up the idea of Africans being in need of the gospel and European civilization. In doing so, the images echo the notions of British national and racial superiority expressed in letters in the present edition and so demonstrate how such imperial ideology continued to persist long after Livingstone's time.

Much of the moral and intellectual justification for a missionary-explorer’s career such as Livingstone’s stemmed from a sense of British national superiority, even as it intersected with notions of racial superiority. For instance, these letters show that his descriptions of the Sotho-Tswana peoples were generally disparaging. Livingstone may have questioned the extreme tone Robert Moffat used when describing the Sotho-Tswana, yet Livingstone also describes the Sotho-Tswana as “degraded beings” in need of raising up to a higher “level of humanity and civilization” (Livingstone 1843b:[5]).

This was typical evangelical-humanitarian parlance in the mid-nineteenth century. When read together, the letters in this collection suggest that even as Livingstone acquired a more nuanced understanding of African knowledge systems than was typical of the period, he oscillated between the more moderate and better informed ideas he acquired during his travels and the dominant tropes of the evangelical missionary movement.

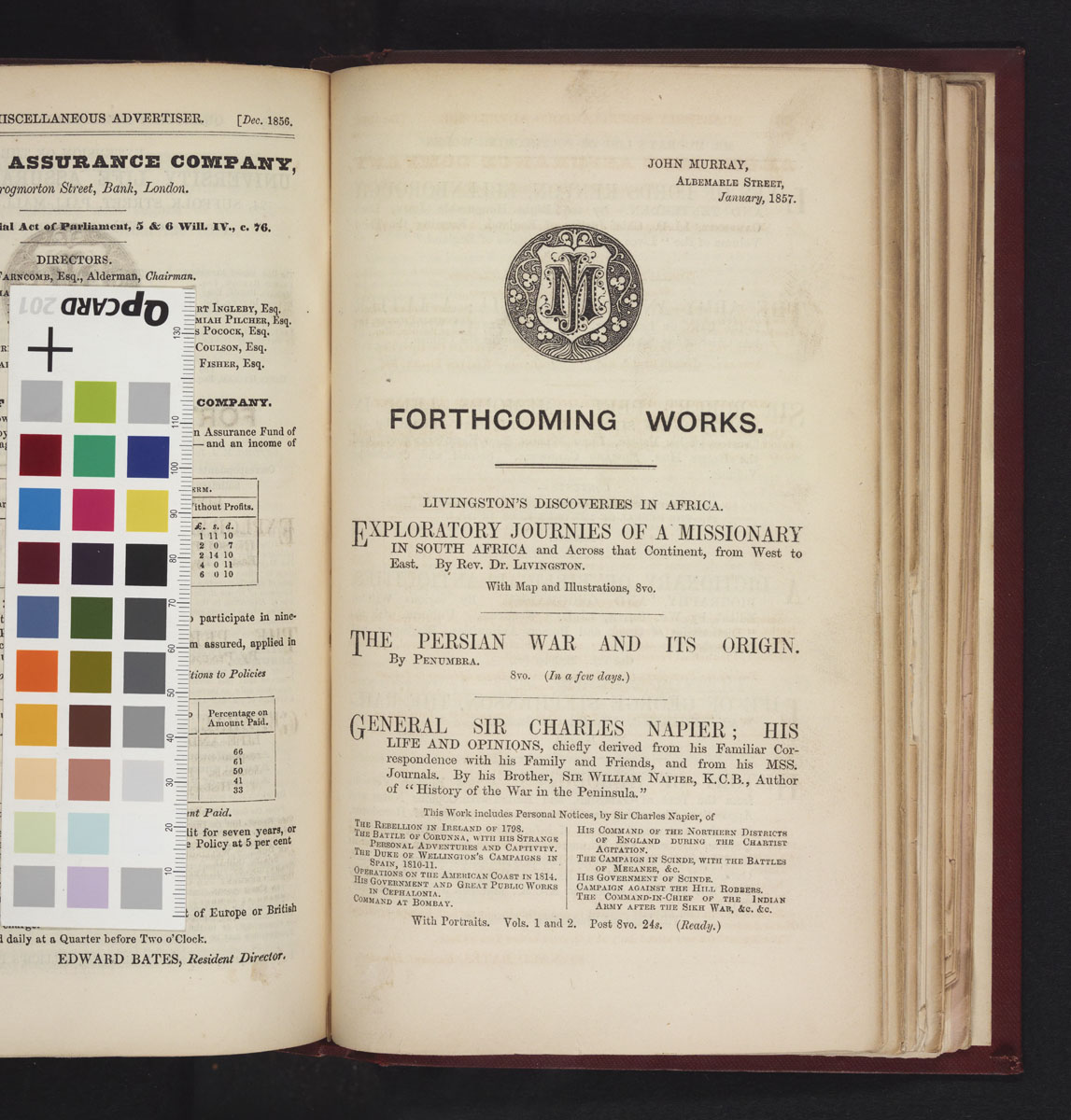

Trade advert for forthcoming works, including David Livingstone's 'Exploratory Journies of a Missionary,' Quarterly Review, 101 (Jan. 1857-Apr. 1857): Jan. 1857, 1. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. Nineteenth-century travelers regularly sought to convert narratives of their journeys into commercial publications, a move that required catering to the expectations of readers regarding the appearance and conduct of foreign peoples. Although Livingstone drew on his first-hand observations in composing as he traveled, mindfulness of many potential audiences also shaped his representations.

Not only the specific recipients of his correspondence but also a potential broader audience may have influenced Livingstone’s stance when it came to depictions of African peoples. For example, in a letter written to the Governor of Angola in March 1856, Livingstone describes the Makololo in complimentary terms, while in some cases also qualifying his observations in a manner that was more typical of European descriptions of Africans in the mid-nineteenth century.

The letter in question recounts how Livingstone had been “entrusted with certain presents and a letter from the Government of Angola for Sekeletu the chief of the people called Makololo living on the Zambesi near the centre of the continent,” then records that the presents had been “well appreciated as could have been expected from a savage nation” (Livingstone 1856d:[1]-[2]). Yet for the most part, Livingstone’s descriptions of Sekeletu and the Makololo in his message to the Governor of Angola were measured and complimentary.

The particular event appears to have excited Livingstone as the prospect of opening up the interior of the subcontinent to sustained trade and commerce seemed to be within reach. This may explain why Livingstone limited criticism as he did of the Makololo. At this time, Livingstone was still on good terms with the Portuguese colonial administration in Angola, and the participation of the Makololo was going to be vital in the establishment of a successful transcontinental trading network.

Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe, 2016. Copyright Jared McDonald. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. In Livingstone's Missionary Travels (1857), the Falls provide a striking symbol of the yet untapped wonders of the African continent and by extension the benefits that will flow through commerce with populations in the interior of the continent. Yet a point rarely noted is that the Falls (as did the Cahora Bassa rapids, which Livingstone visited in 1858) curtailed Livingstone's ambitions for using the Zambezi River as a continuous "commercial highway" (Livingstone's term) into the interior and so made any plans of trade much more dependent on intermediaries.

In the same letter, Livingstone also sees fit to praise Sebituane, the father of Sekeletu, for bringing stability to the region and thus enhancing the prospects for trade, especially of ivory. Livingstone reasons that while it “would have been impossible to have made a way through such a people” as inhabited the central Zambezi River valley, Sebituane “conquered them all, and thereby rendered a good service both to humanity and commerce” (Livingstone 1856d:[5]).

Thus, we are able to see from this collection of letters that Livingstone’s views on Africans and African traditional practices were sometimes relayed with strategic outcomes in mind. Often his observations were tinged with the sorts of insights only someone with his length and depth of experience in Africa could have expressed. His portrayal of African traditional medicine and its practitioners was a further indication of this.

![John Murray III and Anon., David Livingstone - Boat Scene (Painted Magic Lantern Slide), [1857], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND. John Murray III and Anon., David Livingstone - Boat Scene (Painted Magic Lantern Slide), [1857], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND.](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_014067_0001-carousel.jpg)

![Image of two pages from Livingstone's Field Diary XVI (Livingstone 1872h:[2]-[3]). CC BY-NC 3.0 Image of two pages from Livingstone's Field Diary XVI (Livingstone 1872h:[2]-[3]). CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000016_0003-carousel.jpg)

![David Livingstone, Map of Lakes Nyassa and Shirwa [1864?], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND; Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson, CC BY-NC 3.0 David Livingstone, Map of Lakes Nyassa and Shirwa [1864?], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND; Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson, CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000077_0001-tile.jpg)

![Image of a page of David Livingstone, Letter to Robert N. Hayward, 17 July 1843: [7]. Image copyright The Brenthurst Press (Pty) Ltd, 2014. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). Image of a page of David Livingstone, Letter to Robert N. Hayward, 17 July 1843: [7]. Image copyright The Brenthurst Press (Pty) Ltd, 2014. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/critical-reflections-the-manuscripts-1/liv_000538_0007-article-1200.jpg)

![Image of a page of David Livingstone, Letter to John C.L. Marsh, 21 November 1872: [1]. Copyright The Brenthurst Press (Pty) Ltd, 2014. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). Image of a page of David Livingstone, Letter to John C.L. Marsh, 21 November 1872: [1]. Image copyright The Brenthurst Press (Pty) Ltd, 2014. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/critical-reflections-the-manuscripts-1/liv_002626_0001-article-1200.jpg)

!['View of Kuruman.' Image from Lantern Slides of the Life, Adventures, and Work of David Livingstone, Date Unknown: [5]. Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Libraries, Washington, D.C. 'View of Kuruman.' Image from Lantern Slides of the Life, Adventures, and Work of David Livingstone, Date Unknown: [5]. Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Libraries, Washington, D.C.](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/critical-reflections-the-manuscripts-1/liv_012010_0005-article-1200.jpg)

!['Thrown from an Ox.' Image from Lantern Slides of the Life, Adventures, and Work of David Livingstone, Date Unknown: [17]. Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Libraries, Washington, D.C. 'Thrown from an Ox.' Image from Lantern Slides of the Life, Adventures, and Work of David Livingstone, Date Unknown: [17]. Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Libraries, Washington, D.C.](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/critical-reflections-the-manuscripts-1/liv_012010_0017-article-1200.jpg)

![Wooden Box with Inset Cross, Made with Wood from Mary Livingstone's Grave, [After 1862]. Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Object images used by permission. May not be reproduced without the express written consent of the National Trust for Scotland, on behalf of the Scottish National Memorial to David Livingstone Trust. Wooden Box with Inset Cross, Made with Wood from Mary Livingstone's Grave, [After 1862]. Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Object images used by permission. May not be reproduced without the express written consent of the National Trust for Scotland, on behalf of the Scottish National Memorial to David Livingstone Trust.](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/critical-reflections-the-manuscripts-1/liv_012030_0001-article.jpg)

![Commemorative Cross in Presentation Box, Made from the Wood of the Mvula Tree under which David Livingstone's Heart was Buried after his Death in May 1873, [c.1900]. Image copyright National Museums Scotland. Used by permission. Any form of reproduction, transmission, performance, display, rental, lending, or storage in any retrieval system without the written consent of the copyright holders is prohibited. Downloading the images for use by third parties and end users is strictly prohibited, except for private study. Downloading of images for commercial purposes will be treated as a serious breach of copyright and strong legal action will be taken by National Museums Scotland. Commemorative Cross in Presentation Box, Made from the Wood of the Mvula Tree under which David Livingstone's Heart was Buried after his Death in May 1873, [c.1900]. Image copyright National Museums Scotland. Used by permission. Any form of reproduction, transmission, performance, display, rental, lending, or storage in any retrieval system without the written consent of the copyright holders is prohibited. Downloading the images for use by third parties and end users is strictly prohibited, except for private study. Downloading of images for commercial purposes will be treated as a serious breach of copyright and strong legal action will be taken by National Museums Scotland.](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/critical-reflections-the-manuscripts-1/liv_003192_0001-article-1200.jpg)

![Image of a page of David Livingstone, Field Diary III, 14 May-30 June 1866: [37]. Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). Image of a page of David Livingstone, Field Diary III, 14 May-30 June 1866: [37]. Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/critical-reflections-the-manuscripts-1/liv_000003_0037-article-1200.jpg)

![Image of a page of David Livingstone, Notebook, March 1866-March 1870: [43]. Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). Image of a page of David Livingstone, Notebook, March 1866-March 1870: [43]. Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/critical-reflections-the-manuscripts-1/liv_000023_0043-article-1200.jpg)