Livingstone's Missionary Travels Manuscript (1857)

![John Murray III and Anon., David Livingstone - Boat Scene (Painted Magic Lantern Slide), [1857], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND. John Murray III and Anon., David Livingstone - Boat Scene (Painted Magic Lantern Slide), [1857], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND.](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/grid_images/liv_014067_0001-tile.jpg)

Cite edition (MLA): Livingstone, Justin D., and Adrian S. Wisnicki, dirs. Livingstone's Missionary Travels Manuscript. First ed. In Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. 2019. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/c0bd18cf-692f-4843-b896-799cff98351b.

Cite page (MLA): Livingstone, Justin D. "Introduction to the Edition." Adrian S. Wisnicki, ed. In Livingstone's Missionary Travels Manuscript. Justin D. Livingstone and Adrian S. Wisnicki, dirs. Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. 2019. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/c0bd18cf-692f-4843-b896-799cff98351b.

This page introduces the present critical edition. The page provides a brief overview of Missionary Travels (1857), the major work that followed David Livingstone’s famous transcontinental expedition (1852-56), and discusses the scope and achievements of the edition.

|

|

The MLA Committee on Scholarly Editions has awarded Livingstone’s Missionary Travels Manuscript (1857) (first edition) the seal designating the edition as an MLA Approved Edition. Awarded: 30 June 2020 |

Introduction to the edition

Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa (1857) is David Livingstone’s major literary accomplishment. It serves as the primary public statement of both his personal objectives as a missionary and explorer and his theories about the future prospects of south-central Africa. Following publication, Missionary Travels became one of the most influential works on Africa of the mid-Victorian period. It encouraged other expeditionary travellers, inspired numerous missionary ventures, and contributed significantly to the intensification of interest in the continent prior to the “Scramble for Africa” in the late-nineteenth century.

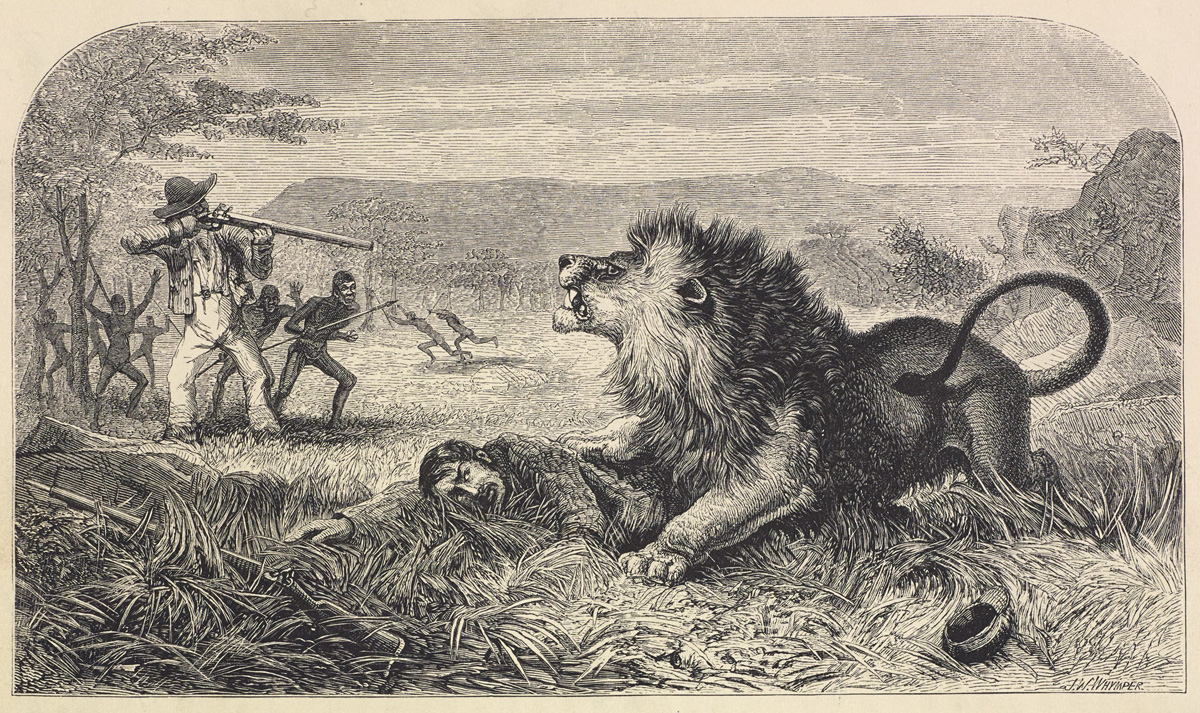

The Missionary's Escape from the Lion. Illustration from Missionary Travels (Livingstone 1857aa:opposite 13). Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. Livingstone was famously attacked by a lion in 1844, an event which left him with a permanently impaired left arm. This illustration became a key part of Livingstone’s iconography and helped mythologize him as a Victorian heroic explorer. As in evidence here, the illustration also played to public expectations about race and stereotypical representations of Africans. However, Livingstone’s writings often complicate or resist such contemporary thinking. Portions of the Missionary Travels manuscript that were excised prior to publication (Livingstone 1857bb:[197]-[227]), for instance, show that he was a fierce advocate of African land rights in the face of colonial settlement in South Africa’s eastern Cape.

This edition provides unique insight into the creation of Livingstone’s best-selling work by focusing on the literary manuscript of Missionary Travels. This manuscript – published here for the first time as a result of the generous provision of digital images by the National Library of Scotland – captures a key moment in the book’s development by revealing how Livingstone and his publisher, John Murray, transformed the experiences of the field into a polished narrative of exploration for public circulation. The numerous instances of correction and redaction across the manuscript’s three volumes provide critical evidence of the composition, revision, and editorial practices that shaped the book as it was prepared for publication.

The present edition engages with the Missionary Travels manuscript in ways that would not be possible in any print format. Free from the constraints of space, the edition offers critically remediated access to Livingstone’s full manuscript; it incorporates digital images of over 1,100 original manuscript pages as well as encoded transcriptions which capture the document’s physical appearance and textual features in detail.

| Images of two pages of the Missionary Travels manuscript (Livingstone 1857bb:[274] and 1857dd:[132]). Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. The page at left (top in mobile) is in David Livingstone's hand, but includes additions from the "red ink man," an anonymous reader employed by Livingstone's publisher John Murray III. The page at right (bottom) is in the hand of Livingstone's brother, Charles, who transcribed parts of the manuscript from Livingstone's dictation; the page also includes later corrections from Livingstone. Together, the pages offer a miniature representation of the complex process of revision that the Missionary Travels manuscript passed en route to publication. |

The edition, moreover, presents Missionary Travels in two forms. The transcriptions of the manuscript are made available alongside the text of the published book (itself almost 700 pages) in order to facilitate comparative analysis. These primary materials are also framed by an array of supporting archival documents as well as critical and contextual essays that, in turn, outline the edition’s underlying methodologies and practices, trace the collaborative literary production of Missionary Travels, and engage in close analysis of the textual and material characteristics of the manuscript.

When Missionary Travels was published in 1857, it became an instant commercial success. The initial print run of 12,000 copies sold out through pre-publication subscriptions, while second (8,000 copies) and third (11,000 copies) printings followed quickly on its heels. Later printings reportedly brought the sales total to 70,000 for the first two years. Such figures were almost unprecedented for a work of exploration and ensured Livingstone’s place alongside earlier celebrated British explorers like James Bruce and Mungo Park.

Missionary Travels is certainly an unusual text in the canon of exploration. Unlike many expeditionary narratives, it was the result of an extended period in south-central Africa that lasted sixteen years (1841-56). In fact, the early part of the book is focussed less on travel than on the events of Livingstone’s eleven years as a resident missionary to the BaTswana in present-day northern South Africa and south-eastern Botswana.

It was, however, Livingstone’s transcontinental journey that most excited readers. This expedition took Livingstone first across Angola to the west coast and subsequently east across sub-Saharan Africa to Mozambique. Livingstone’s eyewitness narrative of the crossing presented his audience with spectacular geographical sightings – including, of course, his celebrated account of “Mosi-oa-tunya” (1855), today known as Victoria Falls.

A photograph of Victoria Falls taken from a helicopter, 2018. Copyright Jared McDonald. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. Livingstone was the first European to visit Victoria Falls and describe them in western print. The Falls, of course, had been known to the local African inhabitants for hundreds of years. Today, in Zambia and Zimbabwe, the Falls are known both as Victoria Falls and as either Shongwe (the Shona name, meaning "rainbow") or Mosi oa Tunya (the Lozi name, meaning "the smoke that thunders"). To Livingstone's credit, he did record both local African names in Missionary Travels (1857aa:518).

Although much of Livingstone’s route had been travelled before by Afro-Portuguese traders, Missionary Travels became the first fully documented transcontinental journey published in English. Moreover, Livingstone undertook his expedition without significant European backing, relying instead on provisions and logistical support from the Makololo people of the Bulozi floodplain of south-central Africa. The extent of this collaboration with a local African group differed conspicuously from most European-led expeditions, which usually employed professional porters to transport supplies and manage the caravan.

Contemporary readers were also compelled by the optimistic vision that animated Livingstone’s writing. In crossing the continent, Livingstone hoped to pioneer “a highway from the coast into the centre of the country” that could facilitate contact with the European world. By enabling so-called “legitimate commerce” in African raw materials and European manufactured products, he believed that such a route would disrupt the central African slave trade by undermining its economic basis. Missionary Travels thus not only documented a collection of significant geographical achievements, but presented a roadmap for African development that captured the imagination of the British public and that rested on the memorable combination of “Christianity, commerce, and civilisation.”

A critical edition of Missionary Travels is long overdue, especially given the influence that the book had in alerting the British public to central African resources and in promoting British colonial intervention. The present edition, however, does not simply present Missionary Travels in the published form that Livingstone and his editors deemed fit for public dissemination. In contrast to scholarship that privileges the published versions of Victorian expeditionary narratives, this edition turns to the archive of exploration and insists on the critical significance of the original manuscript.

By doing so, this edition reveals the multiple hands involved in the making of Missionary Travels and brings to light important material that was excluded from the published book. Prioritising Livingstone’s manuscript allows for a much fuller account of the collaborative making of Missionary Travels than in previous scholarship, and thereby opens a new window on both expeditionary authorship and expeditionary publishing practices in the nineteenth-century.

![Image of Livingstone's Map of Loanda, (Livingstone 1853:[1]), detail. Image from SOAS Library, University of London. Image copyright Council for World Mission. Used by permission for private study, educational or research purposes only. Please contact SOAS Archives & Special Collections on docenquiry@soas.ac.uk for permission to use this material for any other purpose. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). Image of Livingstone's Map of Loanda, (Livingstone 1853:[1]), detail. Image from SOAS Library, University of London. Image copyright Council for World Mission. Used by permission for private study, educational or research purposes only. Please contact SOAS Archives & Special Collections on docenquiry@soas.ac.uk for permission to use this material for any other purpose. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/missionary-travels-manuscript/livingstones-missionary-travels-manuscript-1857/liv_002678_0001-article-crop-1200.jpg)

Image of Livingstone's Map of Loanda, (Livingstone 1853:[1]), detail. Image from SOAS Library, University of London. Image copyright Council for World Mission. Used by permission for private study, educational or research purposes only. Please contact SOAS Archives & Special Collections on [email protected] for permission to use this material for any other purpose. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. This map illustrates the multiple sources of information involved in Livingstone’s cartographical productions. It contains information derived from Portuguese maps and informants as well as from the testimony of local African peoples. This 1853 map thus uses such second-hand information to plot a rough route to the paramount chief of the central Lunda state, the Mwant Yav, whom Livingstone had not visited.

Livingstone’s writings remain important sources for scholars interested in the pre-colonial history of central and southern Africa, the mid-Victorian missionary movement, the culture of nineteenth century exploration, and the development of British imperial ideology. This edition, which includes comprehensive annotations, facilitates further study in all these areas.

The edition’s primary contribution, however, is to scholarship on travel writing and the history of the book. In disclosing how Missionary Travels evolved between different iterations, the research presented here extends critical perspectives on the construction of the authorised record of exploration. This edition reveals how one of the most influential Victorian explorers shaped his narrative for publication and how one of the period’s leading travel publishers mediated the text in the journey to print.

![John Murray III and Anon., David Livingstone - Boat Scene (Painted Magic Lantern Slide), [1857], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND. John Murray III and Anon., David Livingstone - Boat Scene (Painted Magic Lantern Slide), [1857], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND.](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_014067_0001-carousel.jpg)

![Image of two pages from Livingstone's Field Diary XVI (Livingstone 1872h:[2]-[3]). CC BY-NC 3.0 Image of two pages from Livingstone's Field Diary XVI (Livingstone 1872h:[2]-[3]). CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000016_0003-carousel.jpg)

![David Livingstone, Map of Lakes Nyassa and Shirwa [1864?], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND; Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson, CC BY-NC 3.0 David Livingstone, Map of Lakes Nyassa and Shirwa [1864?], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND; Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson, CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000077_0001-tile.jpg)

![Image of a page of the Missionary Travels manuscript (Livingstone 1857bb:[274]). Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/). Image of a page of the Missionary Travels manuscript (Livingstone 1857bb:[274]). Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/missionary-travels-manuscript/livingstones-missionary-travels-manuscript-1857/liv_000099_0274-article-1200.jpg)

![Image of a page of the Missionary Travels manuscript (Livingstone 1857dd:[132]). Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/). Image of a page of the Missionary Travels manuscript (Livingstone 1857dd:[132]). Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/missionary-travels-manuscript/livingstones-missionary-travels-manuscript-1857/liv_000101_0132-article-1200.jpg)