Publishing Livingstone's Missionary Travels

Cite page (MLA): Henderson, Louise. "Publishing Livingstone's Missionary Travels." Megan Ward and Adrian S. Wisnicki, eds. Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. University of Maryland Libraries, 2015. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/2dc0d511-087c-40dc-ab6b-4fe769dd03f7.

This essay uses John Murray’s publication of Livingstone’s Missionary Travels as a case study to explore the role of print and publishers in fostering the fame of nineteenth-century explorers.

Introduction Top ⤴

Many nineteenth-century explorers were celebrities. Whether this fame came from their accomplishments in geography, science, or missionary work, explorers such as Livingstone were often hailed as heroes. Often without regard to the work produced by the explorers themselves, a host of Victorian myth-makers made it their business to profit from turning individual explorers into heroes or villains. Often, the explorer’s reputation would be well established before the adventurer had even returned from the field.

Print was crucial to this endeavour. By the mid-nineteenth century the trade in newspapers, magazines, journals, books and so on had expanded to such a degree that it was possible to reach the masses for the first time. Publications tailored their contents for their intended readers, each contributing information about the latest expeditionary ventures in highly specific ways intended to generate more interest in these explorers - and their publications.

Missionary Travels, American Edition (frontispiece), 1858. Internet Archive |

However, the importance of print in constructing an explorer's legacy did not fade with the traveler's return home. Rather, print raised expectations about the successes or failures that would result from particular ventures, and it was thus necessary for explorers to confirm or contradict the reports produced in their absence. The expeditionary narrative was the main means of doing so and was presented as the explorer's eyewitness account of things that the general public could not hope to encounter for themselves.

These exploration narratives were then subjected to intense scrutiny by a whole range of readers, each with their own specific expectations. Publishers, editors and explorer-authors prepared their narratives with this in mind, attempting to make exploration accounts as widely acceptable and saleable as possible. By acting as intermediates between authors and the reading public, members of the book trade played a significant role in shaping the myths that developed around individual explorers. Moreover, their influence reached beyond their contemporary settings with future generations of readers, and biographers in particular, often relying heavily upon such volumes for knowledge of those who dominated European accounts of nineteenth-century exploration.

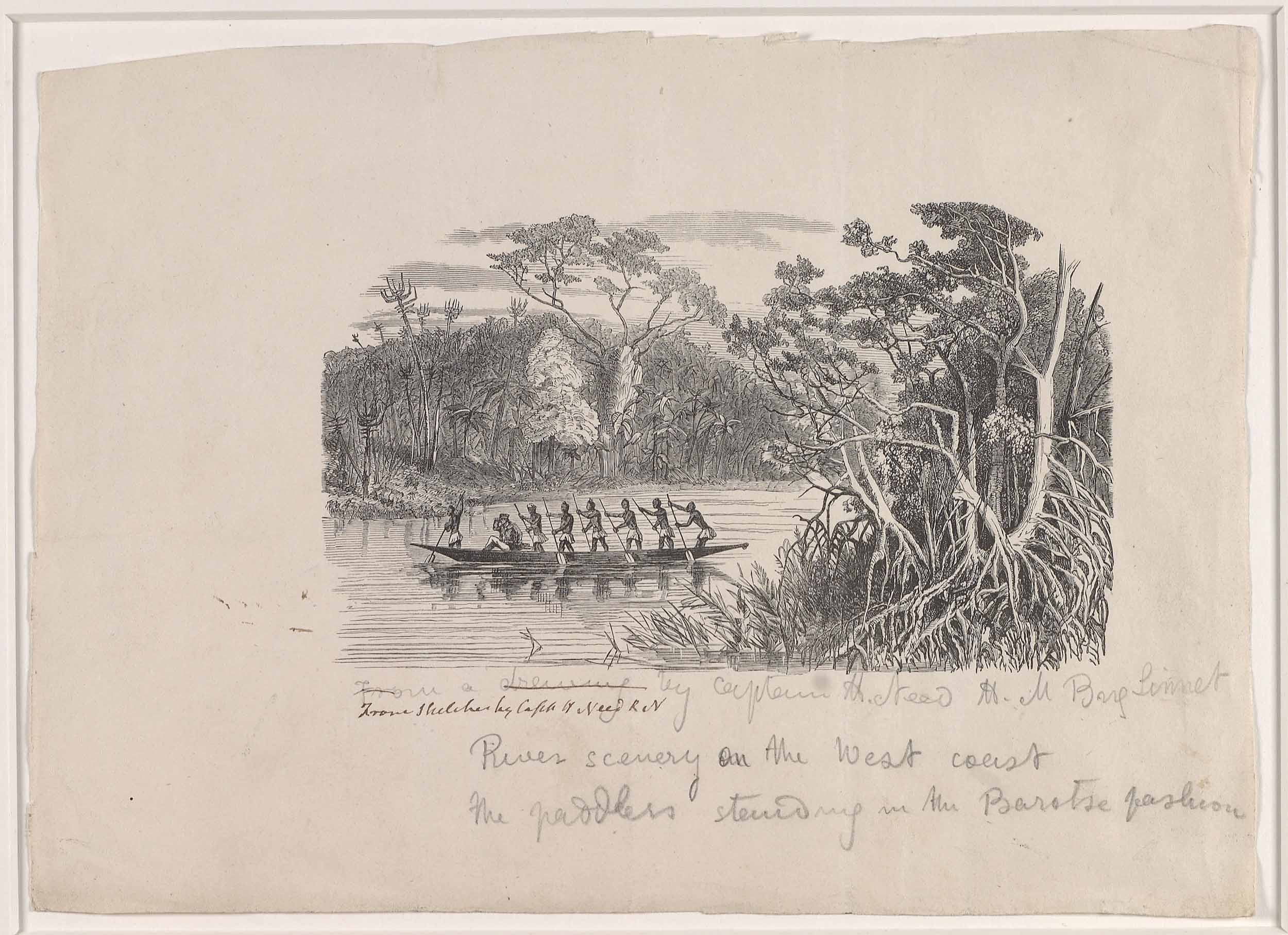

River scenery on the west coast (David Livingstone's Annotated Proof), c.1856-1857. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland

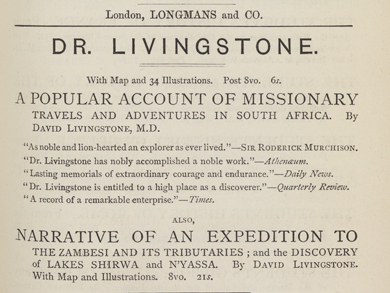

Livingstone's fame and the myths surrounding him owe much to Henry Morton Stanley's “discovery” of him and also the manner of his demise. Long before these events, however, Livingstone's first published narrative was one of the nineteenth century's bestselling books. Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa (Livingstone 1857r) created Livingstone's reputation as a heroic explorer who made contributions to geography, medicine and science, the abolition of the slave trade, and missionary endeavours as well as a whole range of other causes.

The success of this work did not merely help to establish Livingstone in the public eye; it also firmly cemented John Murray's reputation as one of the foremost publishers of geographical works in the period. As John Murray’s role in Missionary Travels exemplifies, print and publishers helped create the cult of celebrity surrounding nineteenth-century exploration.

Missionary Travels: A Case Study Top ⤴

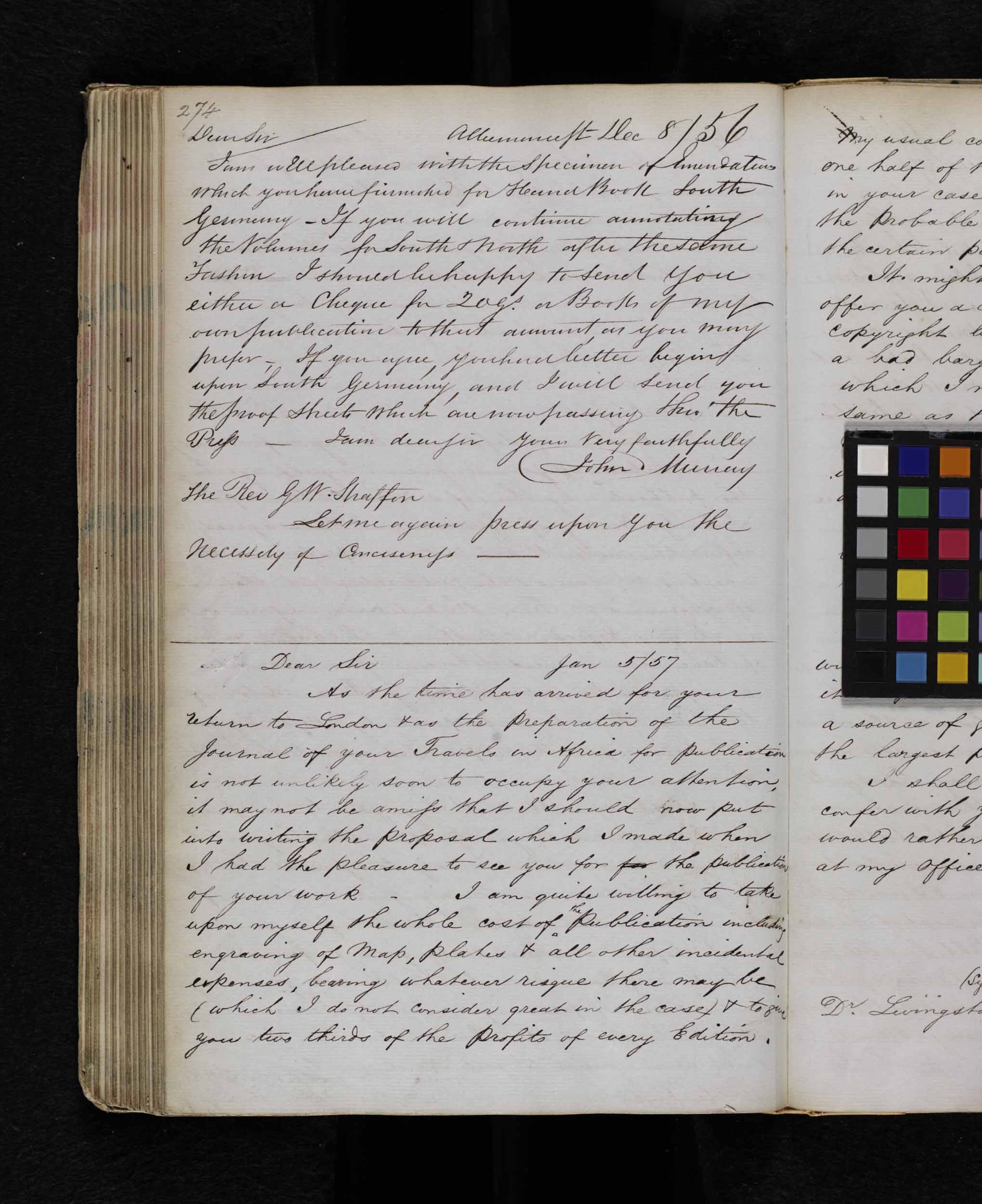

Livingstone received an invitation to publish a volume on his travels even before he had returned from Africa. The President of the Royal Geographical Society, Roderick Murchison, wrote to the explorer in May 1856 explaining that John Murray - one of the best known geographical publishers of the day - was eager for Livingstone to put together a book based upon his experiences in Africa. Three weeks after Livingstone returned to England, Murray iterated his desire to put Livingstone into print, making a formal proposal.

Murray was so anxious to secure Livingstone’s book, he offered unusually generous terms. Writing on 5 January 1857, Murray noted that although it was standard practice to divide any profit equally, he offered in this instance to undertake the entire cost of publication, including the engraving of illustrations and maps, in return for only one-third of the profits (Murray 1857a).

Copy of letter to David Livingstone, 5 January 1857, by John Murray III. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland |

In this exchange, Murray presented himself as a kind of agent operating on the explorer's behalf, playing up the personal satisfaction that he would gain from working with Livingstone whilst playing down the great financial reward such a contract might bring the publisher. Murray was, of course, well aware of the potential market that was already developing for Livingstone's text owing in no small degree to the efforts of Roderick Murchison, who did all he could to ensure that the explorer remained in the spotlight.

Murray wrote to Livingstone again a fortnight later, on 19 January 1857, in order to reiterate his offer (Murray 1857b). He appealed both to his personal interest in Livingstone's work and to his firm's reputation in order to persuade Livingstone to ignore the increasing interest shown by rival publishing houses. By way of incentive, Murray offered Livingstone a two thousand guinea advance on his share of the profits and also noted that the firm would be on hand to provide "literary assistance," an indication perhaps that Murray was all too aware that explorers were rarely naturally gifted writers.

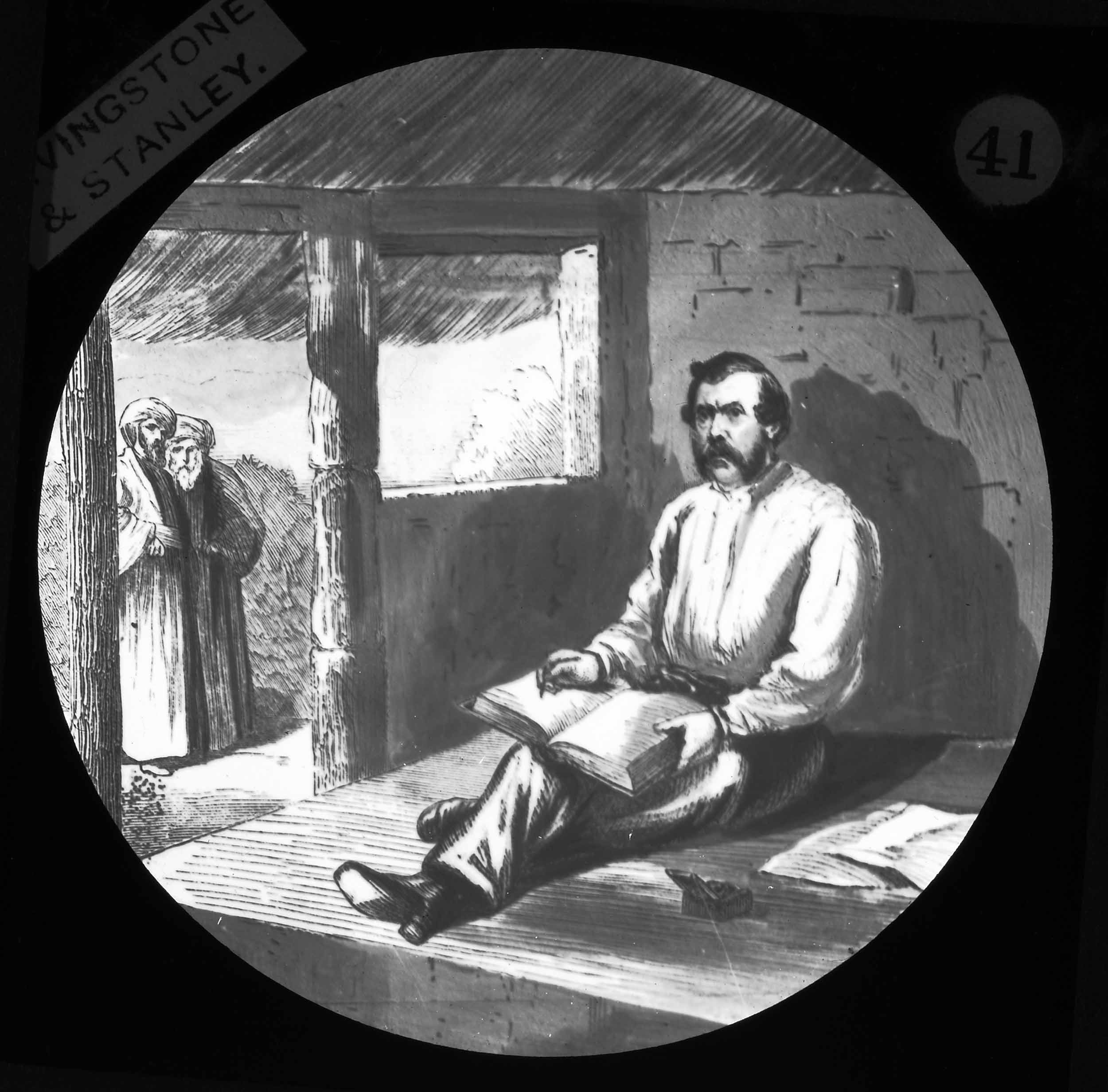

Indeed, Livingstone had privately expressed doubts about his ability to compile a publishable narrative. Nevertheless he accepted Murray's offer and began transforming his field diaries into a manuscript for public consumption. In constructing the manuscript for Missionary Travels Livingstone not only transferred information but also, crucially, transformed that information in an acknowledgement that the rules governing what were recorded in the pages of a field diary were different to those guiding what was appropriate in the pages of a published account.

Livingstone writing in his journal: Magic Lantern Slides, Livingstone and Stanley Series, c.1900. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland |

Livingstone's correspondence with Murray suggests that he was aware of the need to cater his text to the demands of his likely audience, making reference, for instance, to appeasing religious readers and, as he wrote in 1857, providing something to interest "the scientific" as well as ensuring that he did not offend "the sensitive" (Livingstone 1857f; Livingstone 1857n). Thus the manuscript ultimately presented to Murray was the result of negotiation, as Livingstone attempted to make a case for further involvement in Africa in such a way that would ensure maximum impact with minimum offence.

Murray’s influence on Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa is evident from the very beginning. The book begins with a "personal sketch" of the author which was included, so it said, at the request of several of Livingstone's most trusted friends. While Murray is not explicitly acknowledged, correspondence reveals that he was indeed one of those friends. In a letter dated May 1857, for instance, Livingstone revealed that he had taken the advice of Murray and one of his employees, Mr. Binney, and included in the personal sketch information designed to ensure that the book would appeal to both an "intellectual" and a "religious" public (Livingstone 1857f). Livingstone's background, in particular, presented the explorer as a “man of the people”: honest, hardworking, self-educated and, although religious, not overzealous.

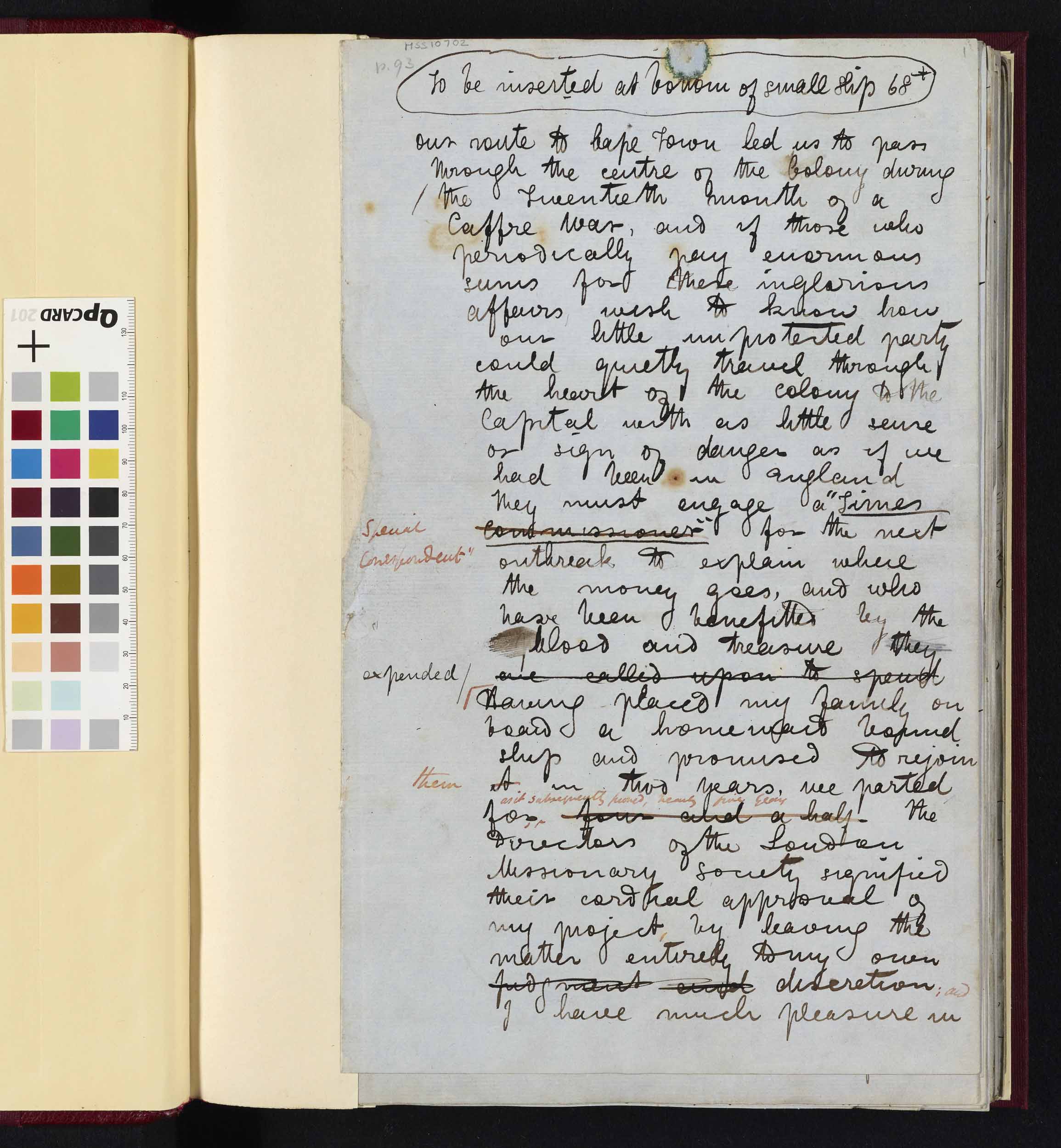

However, the interventions of Murray and his employees were rarely received on such good terms. Despite Livingstone's assertion that Murray would not find him "cantankerous or difficult to deal with," Livingstone regularly wrote to express his dissatisfaction at the "liberties" being taken with his manuscript (Livingstone 1857f). Much of his annoyance was directed towards the reviser Milton. Livingstone was clear in his mind that this individual was thoroughly unqualified to judge the merits of a book of this sort, and argued that the "namby-pambyism" that had "diluted" and "emasculated" the text would inflict considerable harm to the cause which the text was intended to support (Livingstone 1857d; Livingstone 1857e).

A page from the Manuscript of Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa (Part III), January-October 1857, by David Livingstone. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland |

It was not simply the narrative which Livingstone was eager to defend. Livingstone had drawn inspiration from the recently published Arctic Explorations (1856) of Elisha Kent Kane and sought to replicate his style in his own writing. Livingstone appeared proud of the result, recalling the reactions of learned men such as Richard Owen and Roderick Murchison as well as Murray's own employees, Whitwell Elwin and Binney (Livingstone 1857c).

Thus, when the reviser sought to alter stylistic elements of Livingstone's writing his reaction was predictable. Despite Livingstone's belief that the style he had adopted would make the book popular, what he actually meant was that the style adopted would make the book popular with a particular kind of audience. He complained, for instance, on 31 May 1857 that the reviser's interference would result in a text that would be "quite abominable," fearing that it would resemble a "penny primer" in character.

This highlights both Livingstone's fear that the book might simply be seen as an entertaining read and his desire to salvage the scientific and intellectual, not to mention moral, basis of the text. He was adamant, for instance, that that "[m]any of the corrections already put in are not given in Kane's and my book will be read by person's in much the same position as to intelligence as the readers of his" (Livingstone 1857f). Livingstone's desire to distinguish his text from the “penny primer” genre is perhaps also shown by his gentle prodding of Murray as to whether or not an additional, more expensive edition of the text should also be published.

Trade Advert for Forthcoming Works: Exploratory Journies of a Missionary, Quarterly Review 101 (January 1857-April 1857): January 1857, p.1 Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland |

Whilst undertaking a series of public engagements during July 1857, Livingstone had received an enquiry as to the possibility of purchasing such a volume. Although he replied to the interested party that the matter would be left in the hands of Murray, Livingstone clearly believed that there would be a market for such an edition. His retelling of the event in his letter of 11 July 1857 saw Livingstone play the role of ignorant author seeking the expert guidance of his publisher - a marked contrast to his other letters demanding that Murray sack his literary advisor (Livingstone 1857h).

Livingstone's anxieties over the manuscript may be ascribed to the intense scrutiny he predicted it would receive (Livingstone 1857c). He recorded that he was "somewhat anxious lest anything should not be exactly true or rather just my way of saying them should convey ought but the real veritable idea I have of them” (Livingstone 1857g). Livingstone knew that once the text became public property it would be he, not Murray, the reviser or any other Murray employee that would be called to account for its contents.

Pre-empting Murray's dismissal of the reviser, Livingstone informed his publisher that he would consult Francis Galton and Royal Geographical Society Secretary Norton Shaw as to the possibility of them casting an eye over his manuscript. Norton Shaw's agreement to do so involved another prominent geographer in the construction of Missionary Travels.

Complementing the Narrative Top ⤴

Although authorship would be attributed to Livingstone alone, the authority of the volume would be achieved by packaging the narrative alongside a number of other literary and illustrative devices to form the completed book. The appendix included with the first edition was, like the narrative, something of a collaborative effort, for example. The calculations behind the four pages of tables showing "latitude and longitude of positions" were completed by Thomas Maclear, Astronomer Royal at the Cape of Good Hope, using Livingstone's observation book, which Livingstone confessed to Murray and Captain Henry Toynbee was "quite a mass of confusion" (Livingstone 1857n; Livingstone 1857m). Livingstone was eager to include this appendix on the grounds that it would "lend interest to the book among the scientific" - again pointing to the fact that Livingstone purposefully attempted to construct his book so as to attract specific audiences.

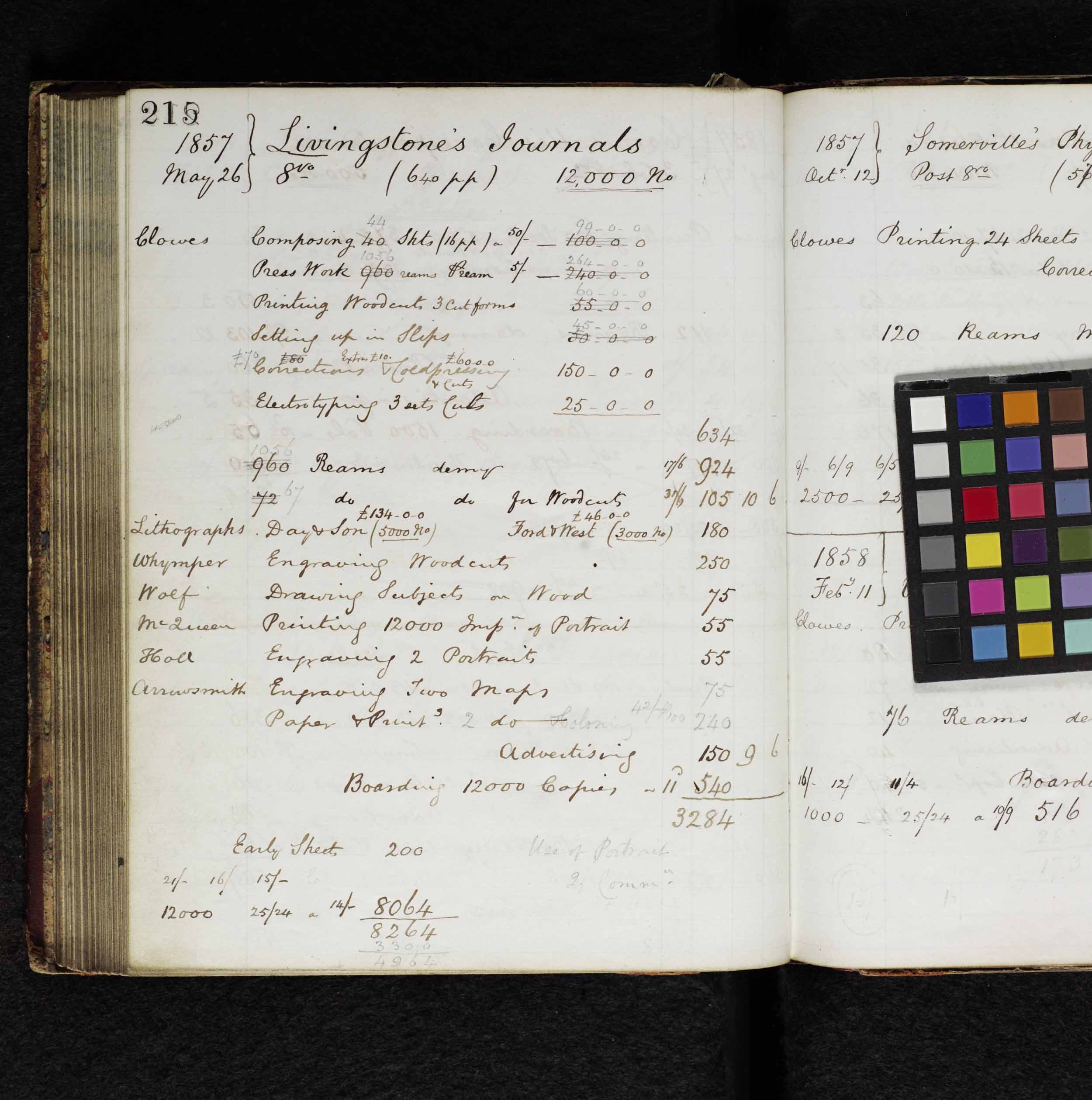

It is interesting, however, that Livingstone discussed the matter with Maclear, Murchison, the cartographer John Arrowsmith and Toynbee before Murray (Livingstone 1857k). Indeed, having obtained their assurances that the observations were worthy of publication, he was, as he told Toynbee, reluctant to accept Murray's assessment that "the majority of readers care little for these details" (Livingstone 1857l). Livingstone appeared to be in a quandary, unsure whether to trust his own instincts as to the interest his observations were likely to attract or to follow his publisher's advice for, as he told Toynbee, "12,000 is a series [sic] expense though it would only be two sheets" (Livingstone 1857l).

In the end Murray and Toynbee together provided a solution. Missionary Travels would carry only a table of longitude and latitude whilst fuller discussion of the observations made during his journeys would be published in the Journal of the Royal Geographical Society (Livingstone 1857o). In this instance then, Murray was only one of a number of individuals who had a hand in the way that this element of the book was presented to the public.

While ultimate control rested with Murray, who succeeded in convincing Livingstone that 12,000 copies of his observations were an unnecessary expense, it is clear that Livingstone felt it necessary to canvas a range of opinions before backing down. Thus, in the case of the appendix, as with the narrative itself, the authority of both the author and the publisher over the construction of the book was constantly being renegotiated.

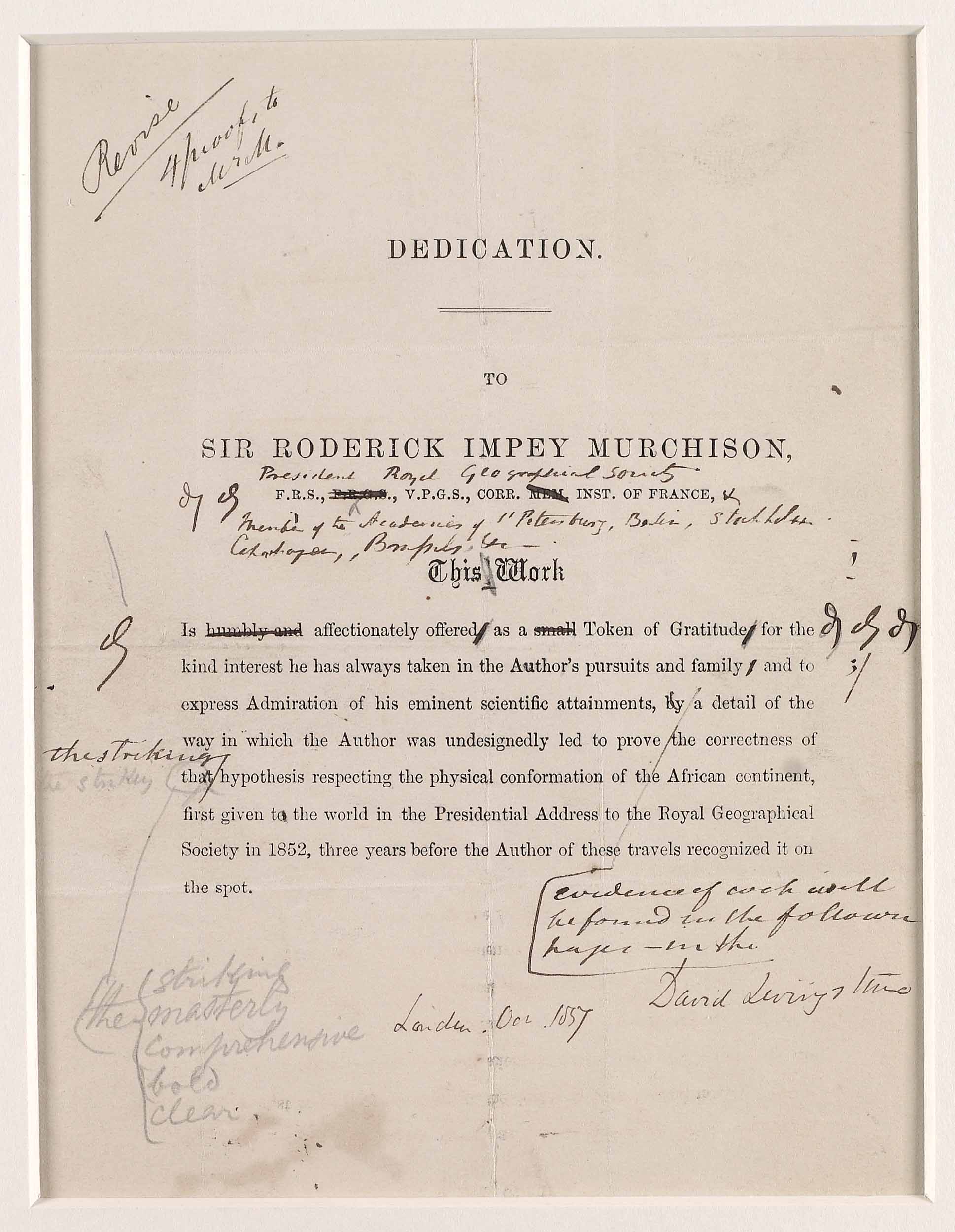

David Livingstone, Dedication page, Livingstone's Missionary Travels (Annotated Proof), c.1856-1857. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland |

While Livingstone felt that the inclusion of the appendix was crucial to establishing the scientific merit of the volume, a number of other elements contributed to this effect. The dedication to Murchison, for example, enabled Livingstone to publicly make a claim about his character, his professional ability, and the value of his text while, at the same time, appearing humble. By thanking Murchison for "the kind interest he has always taken in the Author's pursuits and welfare," Livingstone publicly advertised the fact that his acquaintance with Murchison was not purely professional.

The logic was simple; if Murchison found Livingstone to be of sound character then so too should the reader. Yet Livingstone also emphasised Murchison's "eminent scientific attainments," instructing Murray to ensure that Murchison's titles were placed correctly on the appropriate page, not simply to establish the professional capabilities of his associate, but also as a means of highlighting that those attainments were "verified three years afterwards by the Author of these Travels" which in turn suggested that Livingstone's own work was equally valuable (Livingstone 1857p). Livingstone originally discussed the idea of a "double dedication" addressed to both Murchison and Maclear but was dissuaded by the lack of a precedent, serving to highlight that the inclusion of the dedication in the volume as it appeared, showed his awareness of conventions of the genre (Livingstone 1857j).

Illustrating Missionary Travels Top ⤴

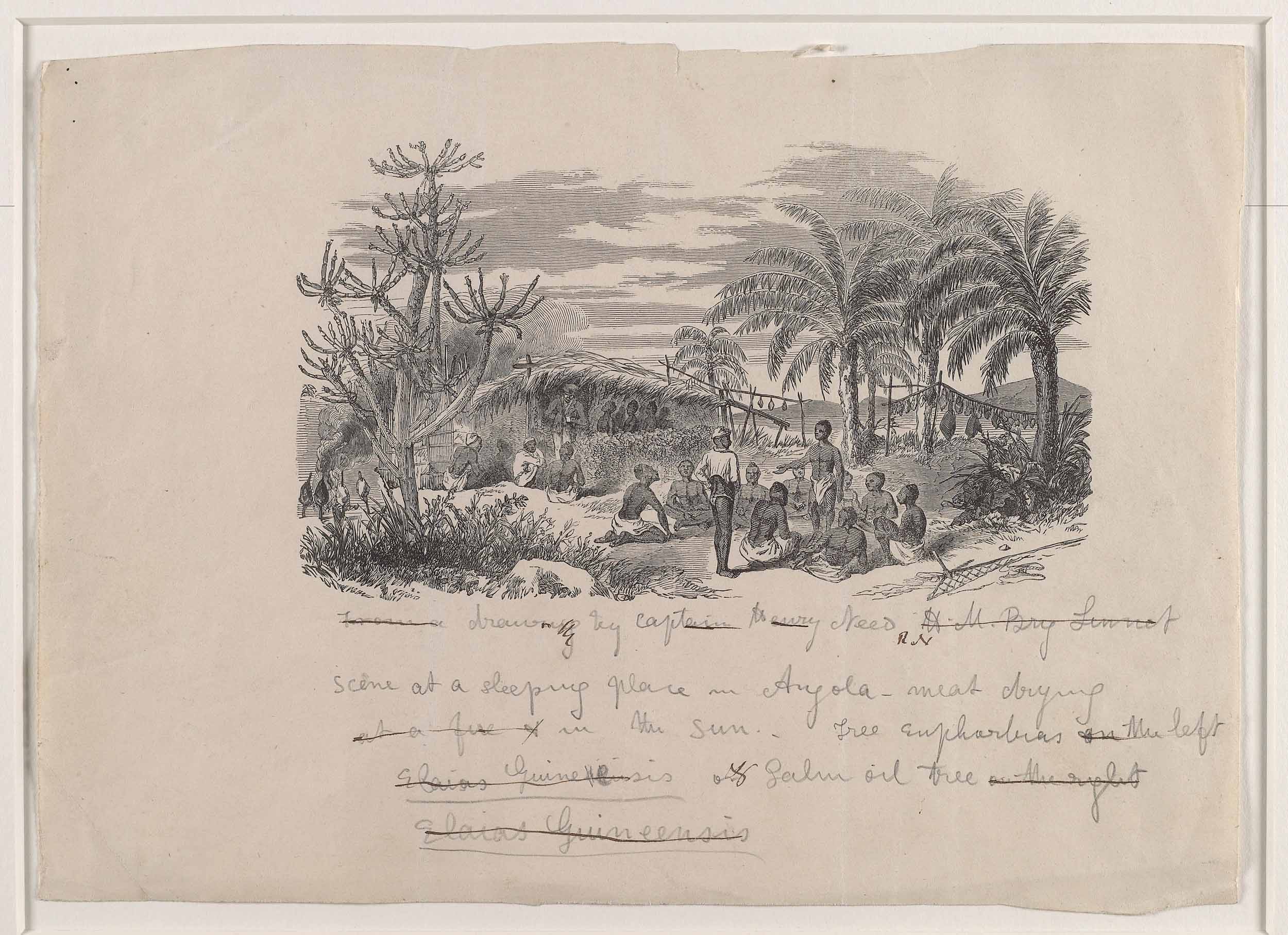

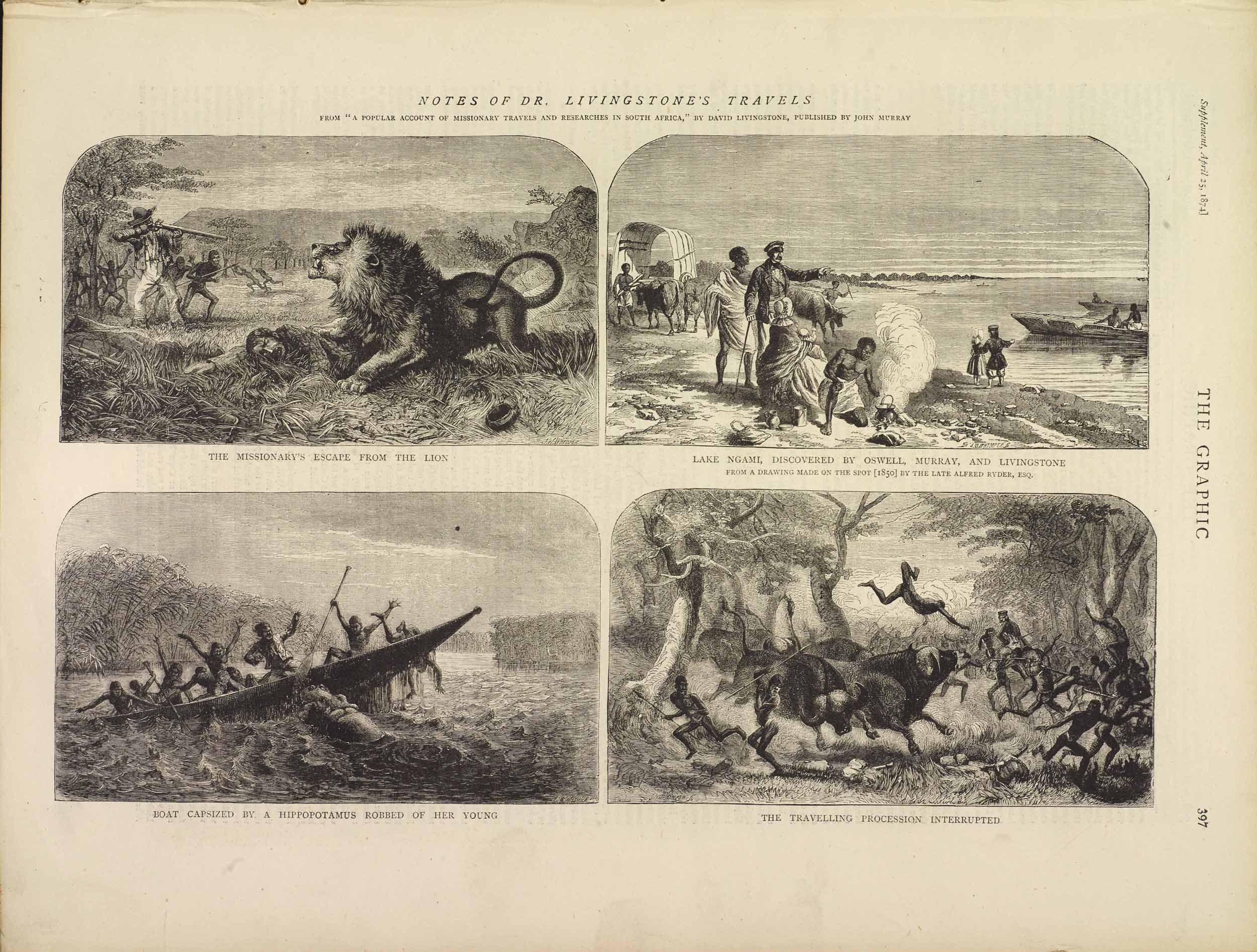

It was not only the production of different textual features which attracted many hands, however. As was usual for an exploration account published by Murray, Missionary Travels contained several illustrations. A number of parallels can be drawn between the construction of Livingstone's narrative and that of the images placed alongside it. Neither reflected a straight-forward eyewitness recollection of the events that unfolded while Livingstone was in Africa, and often they are in tension with one another.

Just as the narrative went through a number of stages — from field diary to manuscript to corrected manuscript and so on, the illustrations underwent a similar process of transformation. Technology at the time was such that pencil sketches were transferred onto woodblocks by an artist and then professional engravers completed the process producing an image fit for publication. However, whereas explorers usually returned from the field laden with sketches, Livingstone readily admitted his inadequacy in this department.

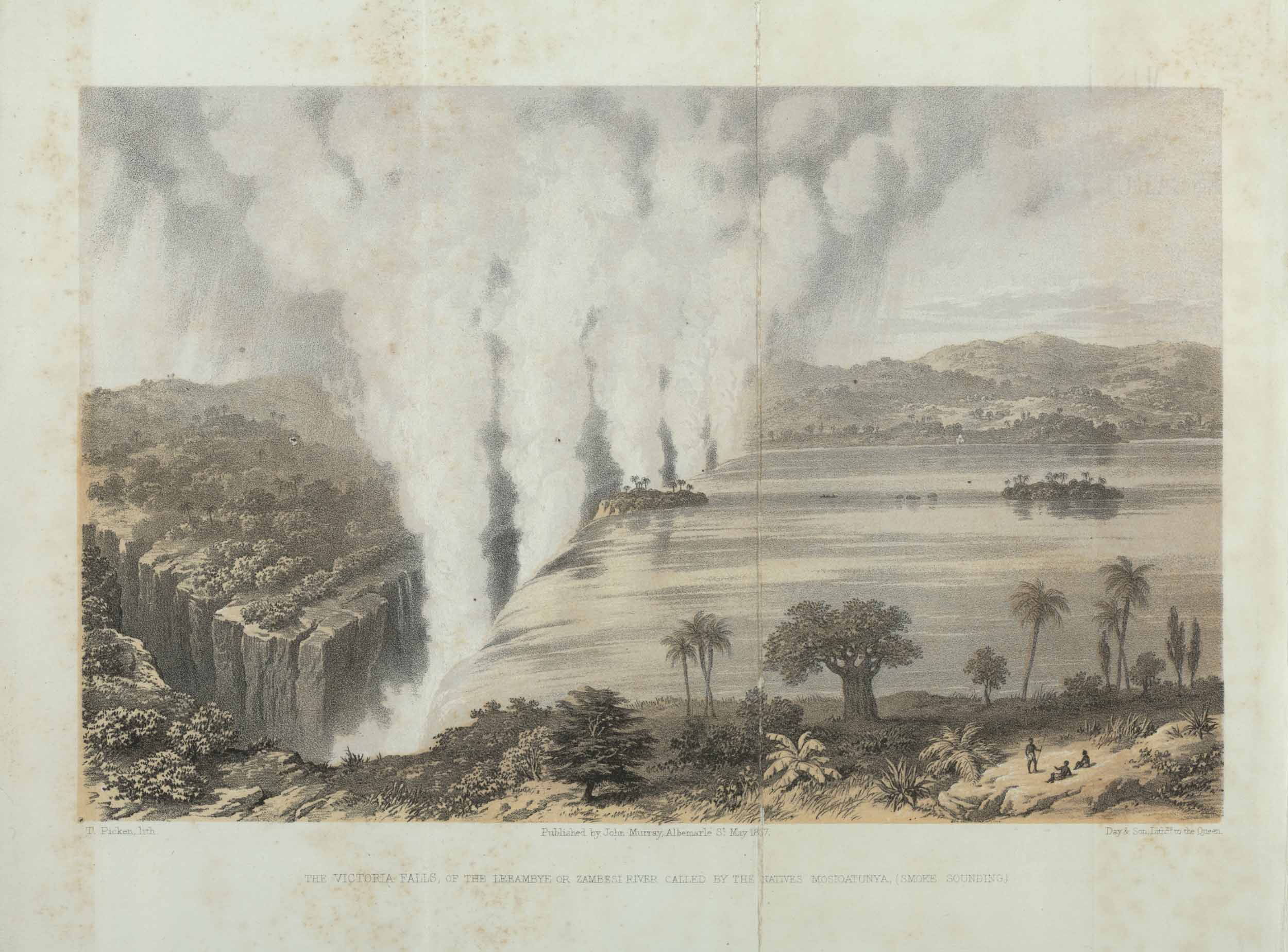

The Victoria Falls, of the Leeambye or Zambesi River Called by the Natives Mosioatunya (Smoke Sounding), Missionary Travels, 1857 Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland

One of the few sketches that Livingstone did return with formed the basis of the frontispiece showing the Victoria Falls. However, Livingstone noted in the text that "The artist has a good idea of the scene, but, by way of explanation, he has shown more of the depth of the fissure than is visible, except by going close to the edge." In this instance, then, Livingstone sought to retain control over the information communicated by the image by using the text.

The rest of the illustrations that made it into the published volume - there were 47 in all including the frontispiece, portrait and two maps - then had to be sourced from a variety of locations.

As the preface revealed, the frontispiece sketch was complemented by those provided by Captain Henry Need and the artist Joseph Wolf, the latter of which were drawn from descriptions provided by Major Frank Vardon and William Cotton Oswell as well as those of Livingstone himself. However, Livingstone admitted that he had struggled to make sense of things visually, being frequently unable to judge distances by sight alone. Such shortcomings made for a difficult working relationship with Wolf. Livingstone's inability to communicate his desires led to his intense dissatisfaction with a number of the images supplied for the book (Livingstone 1857s).

David Livingstone, Scene at a sleeping-place in Angola (Annotated Proof), c.1856-1857. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland

The most famous of these was that of "The missionary's escape from the lion" which Livingstone described as "abominable," complaining that "[e]very one who knows what a lion is will die with laughing at it" (Livingstone 1857b). For the majority of readers, however, the opportunity did not exist to verify the reality behind these representations, and Murray was very willing to publish these illustrations in spite of their inaccuracies. For those readers that may have only looked at the pictures in the book, missing out on Livingstone's frequent attempts to control how they were interpreted through comments in the text, these illustrations were Livingstone's Missionary Travels; they were Africa.

Distributing Missionary Travels Top ⤴

Until the book left the publishing house it could have little impact upon public impressions of Africa. Again a number of individuals were involved in circulating the book, further challenging the assertion that Missionary Travels was the product of a single hand. Although Murray, as publisher, had chief responsibility for ensuring that the distribution and sale of the book was as extensive as possible, his job was made much easier by the interventions of Murchison, who saw to it that there was a captive audience waiting to receive Livingstone's text even before the manuscript was complete, a fact which Livingstone himself was well aware of (Livingstone 1857c).

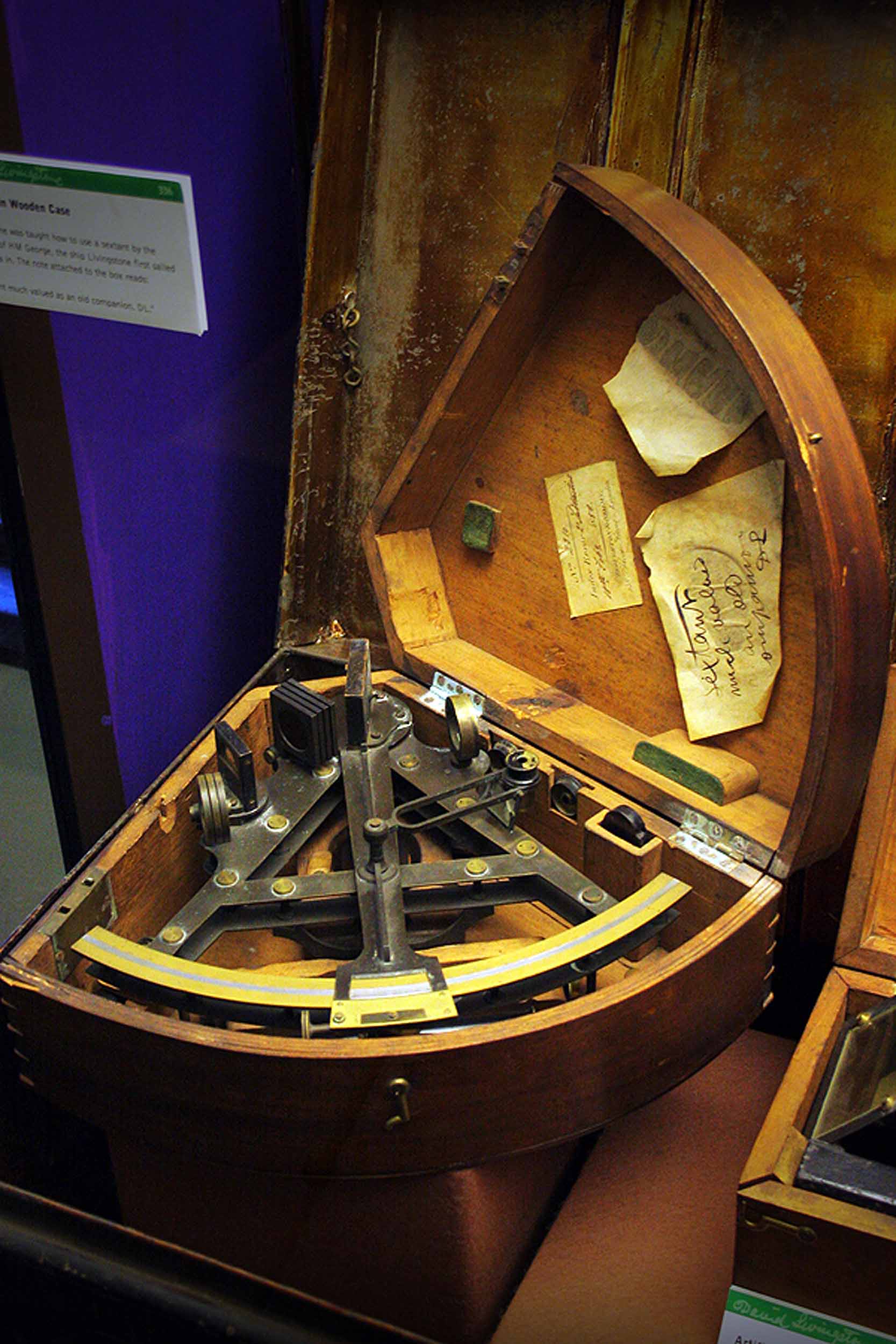

It was not only Murchison, however, who had raised expectations. Livingstone had intended to remain in England for a few months only and thus Murray expected the book to be ready by Easter. Delays, however, meant that by 27 March Livingstone's manuscript was far from complete (Livingstone 1857a). This though, had not prevented Murray from advertising the book's imminent publication in The Times only a few days earlier. Murray also announced that Livingstone's Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa would be the only official account of his work in Africa, encouraging the public to hold out for Murray's publication since it was the only book authored and thus authorised by Livingstone himself.

Estimate book entry for Livingstone's Missionary Travels, first edition. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland |

Both Livingstone and Murray were becoming increasingly frustrated by attempts both within and beyond Britain to produce rival volumes. Each of these piracies claimed to be the product of Livingstone's hand or to have his full consent although these claims could not have been further from the truth. Both men worried that these projected publications would undermine the popularity of Missionary Travels when it was finally published and that they would also result in inaccurate claims about Africa being wrongly attributed to Livingstone. They were so worried about such eventualities that they went to lengths to dissuade the public from taking these works seriously, utilising letters columns, book adverts and even the space of the finished published volume itself to draw attention to the wrongdoings of less respectable publishing houses.

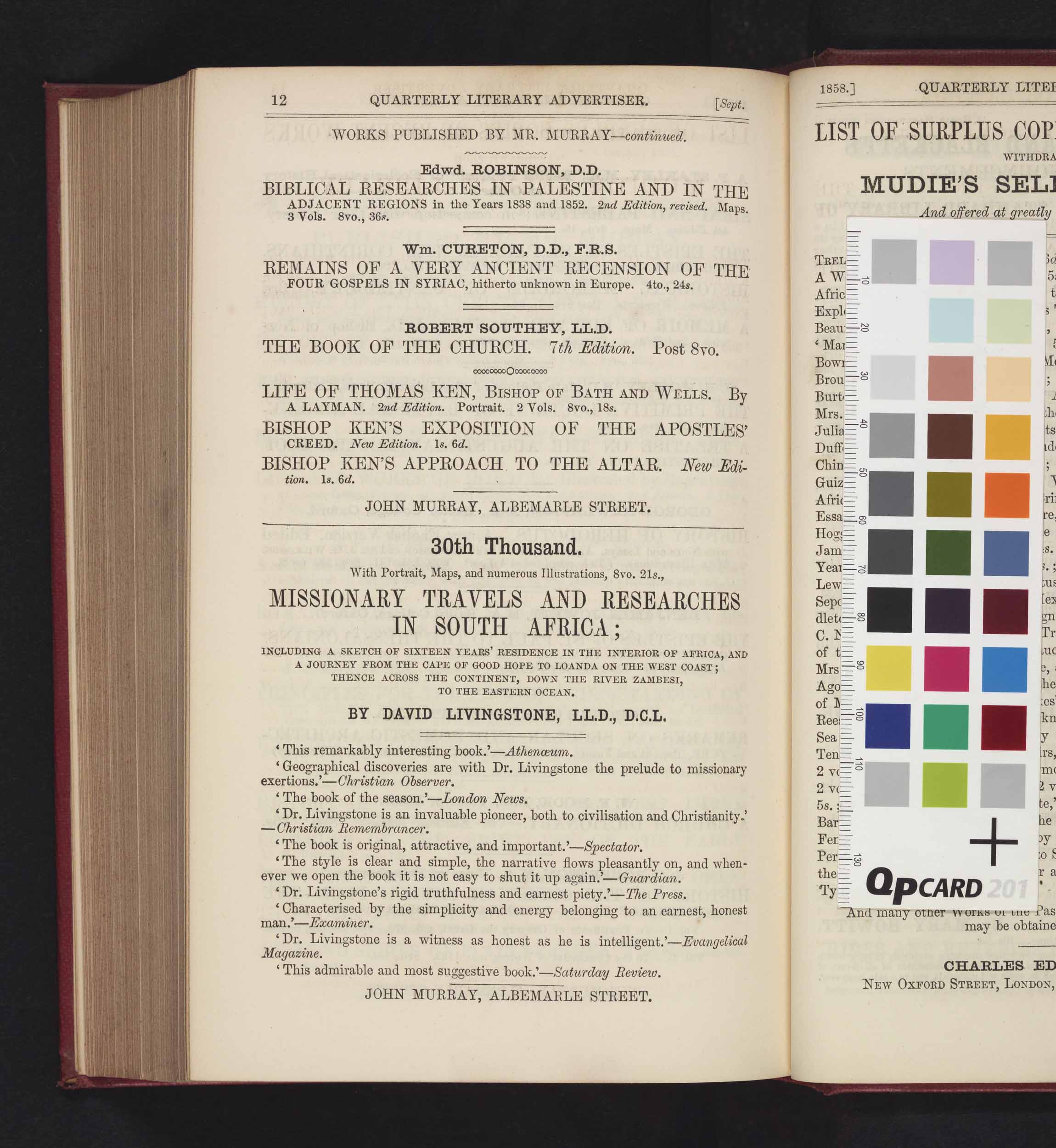

Despite these concerns, however, Murchison and Murray's attempts to create a market for the book appear to have worked to tremendous effect, earning Livingstone a significant sum in the process. The first edition of 12,000 copies sold out immediately despite its price tag of one guinea. To cope with the demand, Murray ordered the printing of another 8,000 copies of the 689 page volume. By the beginning of December this run too had sold out and Murray sent another 5,000 to the presses (Livingstone 1857q). He announced the fact that 25,000 copies in all had now been printed in the 12 December edition of Notes and Queries, informing its readers that "a fresh delivery of this work will be ready next week, when Copies may be obtained of every Bookseller in Town or Country."

Trade Advert: 30th Thousand. Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa, Quarterly Review 104 (July-October 1858): September 1858, p.12. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland |

Such adverts not only let potential customers know that the book would soon be available again but were also a means of telling people that it was a very successful book, one that was in high demand, one which should be read. A letter in which Livingstone relayed the tale of a friend in Manchester who only obtained the book after "offering 2/6 to any boy who would procure it for him" compliments these kinds of adverts and gives greater insight into the market for Missionary Travels (Livingstone 1857q).

Popularising Missionary Travels Top ⤴

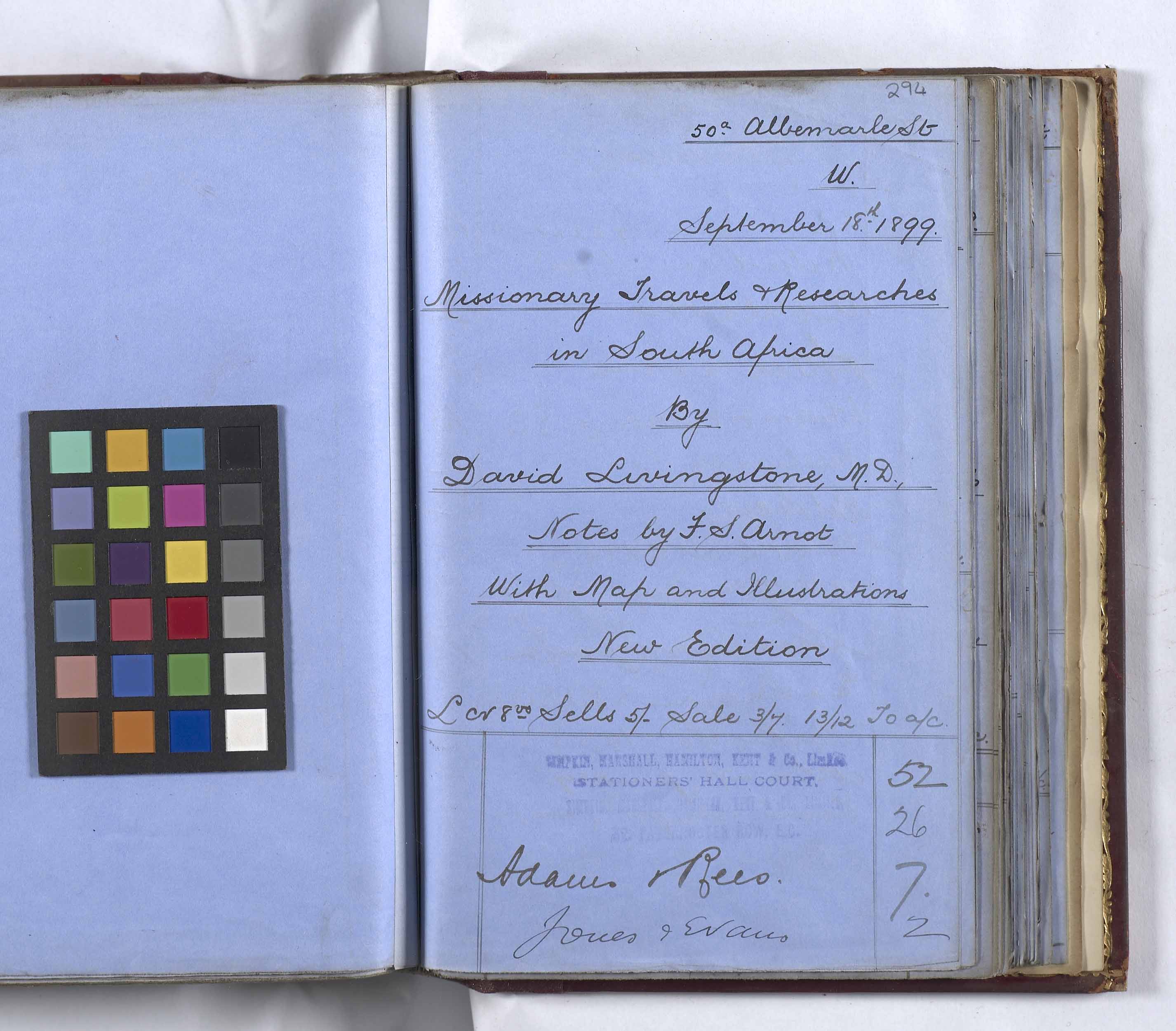

The tremendous success enjoyed by this volume perhaps explains why Murray waited until 1861 to publish A Popular Account of Missionary Travels in South Africa even though Livingstone had authorised the production of an abridged volume only three months after the first edition appeared. With a full-length volume selling so well there appears to have been little economic incentive to produce a cheaper edition straight away. Indeed one of Murray's Copies Ledgers reveals that the firm had another run of 5,000 copies of the initial work printed in March 1858 followed by another thousand which included an index, just a month after Livingstone authorised the abridgement.

Furthermore Livingstone had left the matter entirely in Murray's hands effectively giving him free reign to construct and market the shorter publication as and when he saw fit (Livingstone 1858). Whitwell Elwin was selected to compile the abridgement. He had experience of both authorship and editorship particularly through his post as editor of the Quarterly Review between 1853 and 1860. Elwin had also been involved in the production of the original Missionary Travels offering Livingstone guidance on his manuscript making him well placed to undertake the task of cutting the original text.

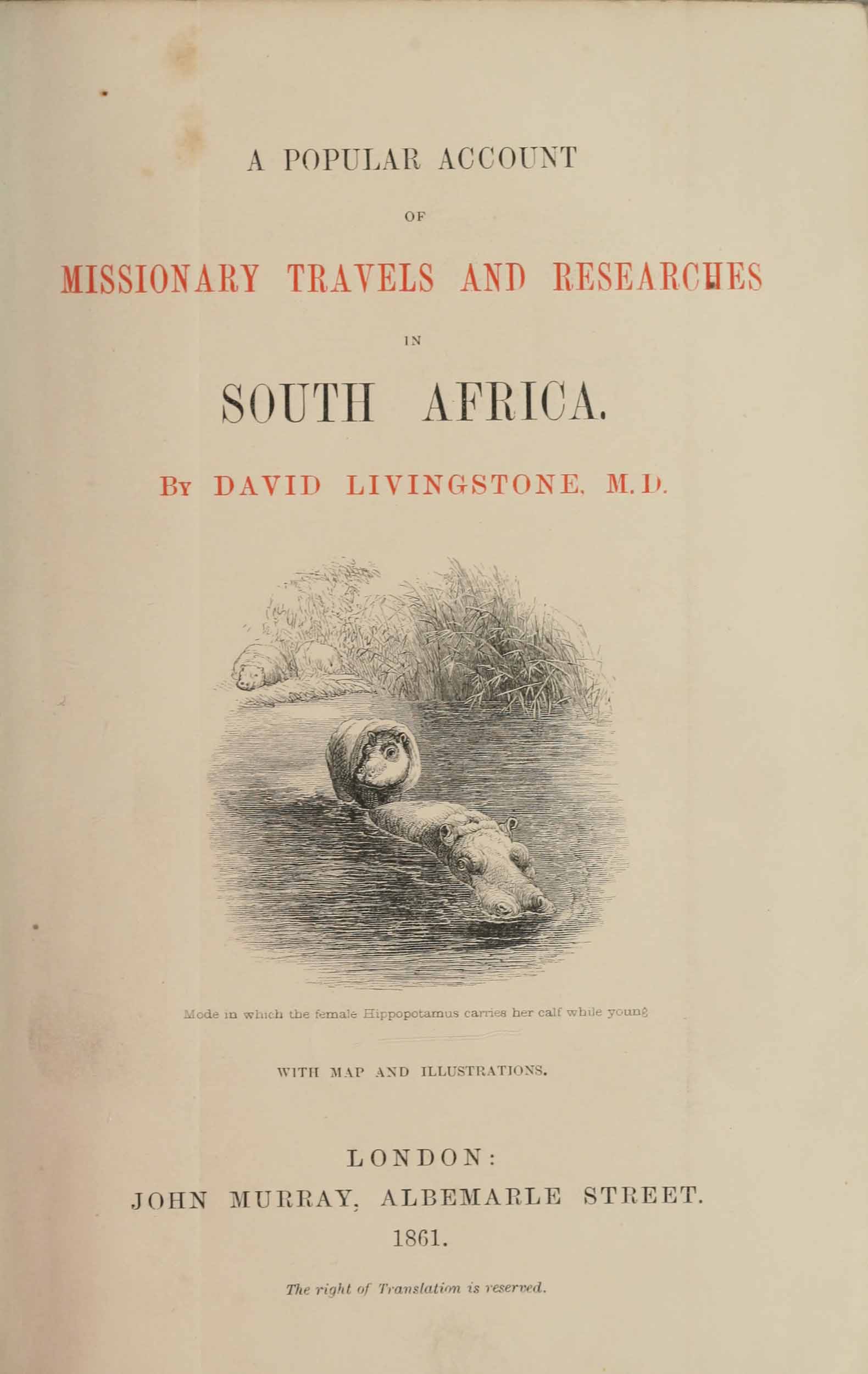

And cut he did, reducing the text from 687 pages to 435. It was not only the text that changed, however. Various textual devices that Murray had moulded for the first book were also altered. The title page for instance contained notable differences. Beyond the fact that the title was now A Popular Account of Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa, Livingstone's professional associations were replaced simply with M.D. Moreover, the illustration of the tsetse fly which had been included in the first volume on Livingstone's insistence was replaced with the altogether more friendly looking female hippopotamus and her calf. Additionally, the volume now came "with map and illustrations," as opposed to "with portrait, maps by Arrowsmith, and numerous illustrations." Furthermore, the dedication and preface were removed so that the reader proceeded directly to the contents page.

A Popular Account of Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa (John Murray, London), 1861, by David Livingstone. Internet Archive |

Thus, whereas the original volume utilised the space of the book prior to the beginning of the narrative to establish Livingstone's status as an authoritative speaker on Africa through his association with various learned societies and individuals, Elwin and Murray evidently regarded such steps as unnecessary in the Popular Account. This demonstrates how publishers considered that it was not simply the narrative that needed to be altered to make a book appropriate for a “general” or non-scientific audience.

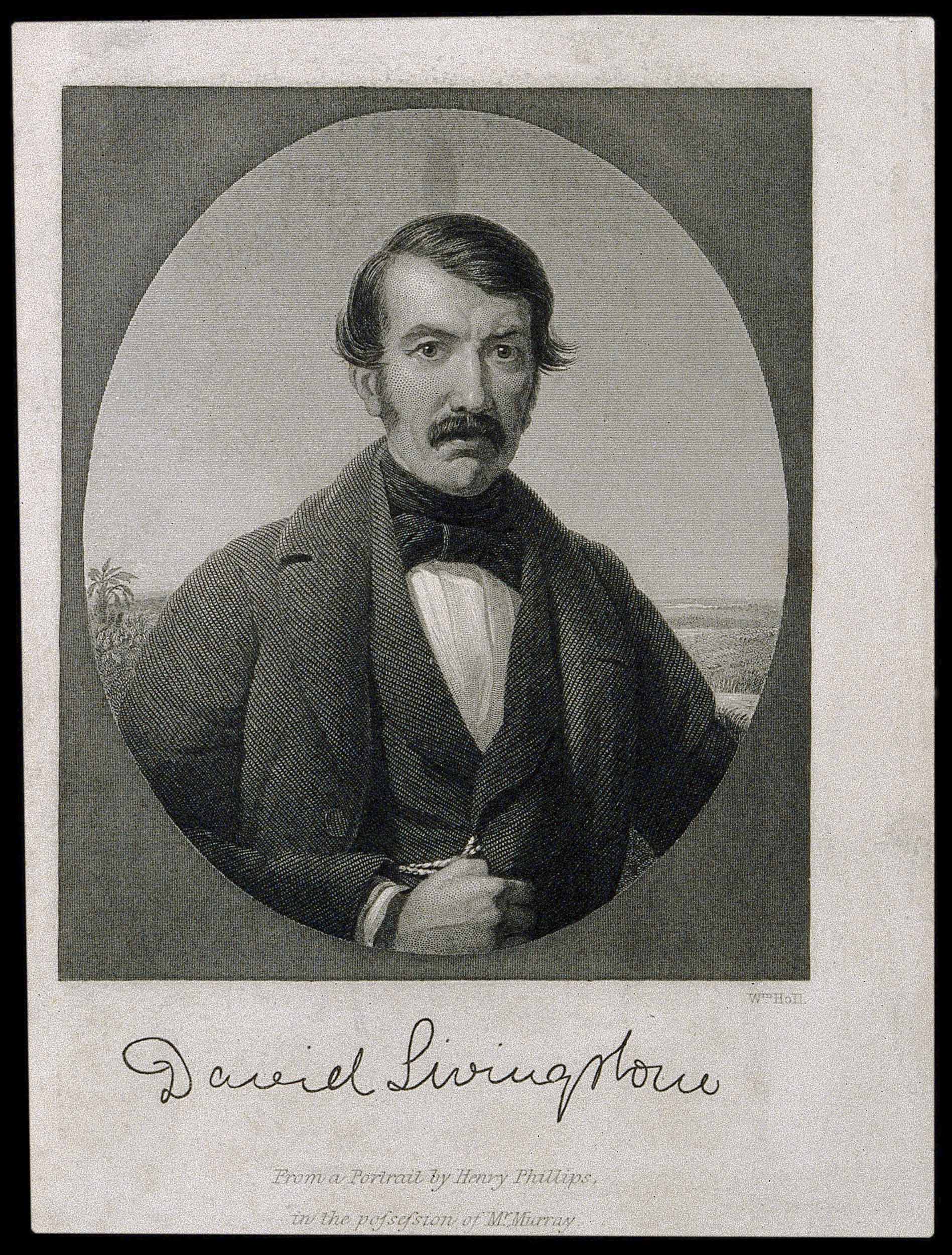

The popular account retained the majority of images that had been included in the original full-length work, yet there were some notable omissions including the author's portrait. By 1861 the attention that Livingstone had received was such that it was no longer necessary to introduce the public to Livingstone in the same way that it had been in 1857. Arrowsmith's detailed map and the tables of longitude and latitude which Livingstone had championed first time round were also discarded, highlighting how Murray had a much more freedom to construct the Popular Account with Livingstone out of the way.

Murray did not only remove elements that had appeared in the full-length editions, however. He also added features to the text, suggesting that although economic motives most likely guided a number of the decisions taken about this work - the abridgement cost considerably less to publish, and subsequently retailed at only six shillings - they were not the only considerations that came into play, suggesting that a “popular” edition did not necessarily have to be cheap in Murray's eyes.

John Murray Sales Subscription Book: David Livingstone Book Sales of Missionary Travels, 18 September 1899 Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland |

Murray's inclusion, for instance, of the an extract from the journal of Captain Hyde Parker as an appendix was an additional expense that did not appear in Murray's original estimate of the cost. However, included as it was, it provided information to the reader about the potential for European settlement around the Zambezi that could either be read in addition to the condensed narrative or by itself.

Another inclusion that did not appear in the initial print runs of Missionary Travels was the index. This encouraged the reader to utilise the book as a reference text, rather than necessarily reading it from cover to cover. Interestingly, in light of the distinctions that appeared to be drawn between scientific and “general” audiences, the index specifically included a section entitled “Scientific names of plants and animals noticed in the foregoing work,” which perhaps reveals that this distinction was not as clear cut as it may first appear. Despite the ongoing success of the original version of Missionary Travels and the appearance of various pirated editions attempting to pre-empt the release of an official popular version, Murray still managed to attract a market for the Popular Account, selling in excess of 10,000 copies.

Reviewing Missionary Travels Top ⤴

Although sales figures themselves reveal much about the publishing sensation surrounding Missionary Travels, they do not provide insights into how readers experienced Livingstone's text. Periodical reviews can give a richer understanding of how different people encountered the book, as well as the discussions which dominate the Livingstone-Murray correspondence.

For instance, the personal sketch included at the beginning of the narrative at the request of Murray came to bear directly upon many reviewers' assessments of Livingstone's writing style. Some reviewers explicitly equated his plain, simple and trustworthy character with a plain, simple and trustworthy narrative. However, Livingstone's style was, of course, one of the elements that he had discussed with Murray and consciously worked at in order to make his book "popular" and "saleable" (Livingstone 1857d; Livingstone 1857e; Livingstone 1857f). His attempts to replicate Kane's style in Arctic Explorations reaped rewards, with some reviewers explicitly drawing parallels between the two authors. Livingstone's success in this regard was two-fold, with reviewers not only making the desired connection, but also doing so without apparently realising that Livingstone had attempted to engineer this.

Portrait of David Livingstone, Missionary Travels, American Edition, 1876. Copyright Wellcome Library, London. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International |

Many reviewers were happy to excuse the “unworked” nature of Livingstone's text on the grounds that he was a missionary traveller by trade and could not be expected to excel in literary endeavours. The attractiveness, or otherwise, of Livingstone's style had much to do with the particular persuasion of the reader though. The Ladies' Repository, for example, preferred Livingstone's narrative to that of the German explorer Heinrich Barth on account of its "romantic attraction" and asserted that although it was educational, it could also be devoured for "literary enjoyment." The Athenaeum echoed this assertion noting, the text's poetic character.

However, Margaret Oliphant's review for Blackwood's Magazine was less generous, claiming that "it is to the credit of this generation, which loves 'style' so much, and is greatly influenced by literary graces, that a work so entirely devoid of both should, nevertheless have attained so remarkable a popularity." Indeed, as Pettit explains, the more “serious” British periodicals sometimes took Livingstone's crudeness of style as evidence of a lack of breeding and scientific training; an assertion which the personal sketch could be said to prove.

The personal sketch was also utilised to different ends in discussions of Livingstone's credentials as a missionary. Catholic publications seemingly struggled to assess Missionary Travels for fear of praising protestant missionary activity. However, after highlighting the fact that Livingstone's "antecedents were Hebridian Catholics in one or two removes" it became easier for some to praise his work.

However, while his lack of "professional and pietistic whinings" were admired in some quarters, others read this as evidence of his lack of commitment to missionary endeavours. The Dublin Review, for instance commented that "no one in reading his account of himself could say that missionary labours were his principal occupation." This in itself, however, did not worry the reviewer to any great degree, who was firm in his conviction that "[w]e are more than reconciled to what so many have objected to — the title of 'Missionary Travels,' prefixed to the work."

Missionary Travels Illustrations from "The Life and Labours of David Livingstone," The Graphic, 25 April 1874, by Henry M. Stanley. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland

Although intended to praise the book, such comments also alerted the reader to the fact that its reception as a book had been problematic. Even through an initial examination of the reception of the personal sketch and Livingstone's style it quickly becomes clear that the author and publisher had some degree of success in shaping the way that readers responded. However, it is also evident that readers did not respond uniformly.

Although the initial edition of Missionary Travels attracted much attention, the market for the abridgement was created largely without the help of the reviewing periodicals. Although a few publications, mainly of religious persuasion, carried notices heralding the release of the abridgement, generally it excited little interest among the reviewing community suggesting that despite the significant reworking and repackaging of the volume by Murray and Elwin, the work was held to offer little that had not already been provided for the reader.

Of course, this in many ways reflects the fact that reviewing publications were so often targeted at those classes who did not need to wait for a 6 shilling volume to emerge. Even those publications that explicitly targeted less affluent readers often felt it necessary simply to announce that a less expensive edition was now available for purchase without elaborating any further upon the work's content.

Examining these reviews alongside the printed volumes and pre-publication correspondence provides insights into Missionary Travels that cannot be gained from examining the published works alone. Taken together, these sources highlight the many individuals that came together, at times uneasily, to produce Livingstone's most famous work and complicate simple understandings of single authorship. Moreover, the sources reveal the many lives that Missionary Travels had – as authorised scientific volume, popular work, and religious document – as well as its afterlives: in advertisements and sales, and in building both John Murray and Livingstone’s reputations in and beyond the nineteenth century.

Works Cited Top ⤴

Livingstone, David. 1857a. “Letter to John Murray III, 27 March [1857].” MS. 42420, ff. 8r-9r. National Library of Scotland. John Murray Archive.

Livingstone, David. 1857b. “Letter to John Murray III, 22 May [1857].” MS. 42420, ff. 29r-32v. National Library of Scotland. John Murray Archive.

Livingstone, David. 1857c. “Letter to John Murray III, 26 May 1857.” MS. 42420, ff. 33r-36v. National Library of Scotland. John Murray Archive.

Livingstone, David. 1857d. “Letter to John Murray III, 30 May [1857].” MS. 42420, ff. 37r-40v. National Library of Scotland. John Murray Archive.

Livingstone, David. 1857e. “Letter to John Murray III, 30 May 1857.” MS. 42420, ff. 41r-44v. National Library of Scotland. John Murray Archive.

Livingstone, David. 1857f. “Letter to John Murray III, 31 May 1857.” MS. 42420, ff. 45r-48v. National Library of Scotland. John Murray Archive.

Livingstone, David. 1857g. “Letter to John Murray III, 3 June 1857.” MS. 42420, ff. 49r-50v. National Library of Scotland. John Murray Archive.

Livingstone, David. 1857h. “Letter to John Murray III, 11 July 1857.” MS. 42420, ff. 63r-64v. National Library of Scotland. John Murray Archive.

Livingstone, David. 1857i. “Letter to Henry Toynbee, 25 July 1857.” CWM/LMS/Livingstone Wooden Box, item 106. University of London. School of Oriental and African Studies.

Livingstone, David. 1857j. “Letter to John Murray III, 4 August 1857.” MS. 42420, ff. 72r-73v. National Library of Scotland. John Murray Archive.

Livingstone, David. 1857k. “Letter to Henry Toynbee, 20 August 1857.” MS. 7329 16. Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine. Library.

Livingstone, David. 1857l. “Letter to Henry Toynbee, [22-27 August 1857].” MS. 7329 70. Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine. Library.

Livingstone, David. 1857m. “Letter to Henry Toynbee, 22 August 1857.” MS. 7329 17. Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine. Library.

Livingstone, David. 1857n. “Letter to John Murray III, 24 August 1857.” MS. 42420, ff. 74r-77r. National Library of Scotland. John Murray Archive.

Livingstone, David. 1857o. “Letter to Henry Toynbee, 4 September 1857.” MS. 7329 19. Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine. Library.

Livingstone, David. 1857p. “Letter to John Murray III, 27 September 1857.” MS. 42420, f. 80r. National Library of Scotland. John Murray Archive.

Livingstone, David. 1857q. “Letter to John Murray III, 25 December 1857.” MS. 42420, ff. 87r-88r. National Library of Scotland. John Murray Archive.

Livingstone, David. 1857r. Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa. London: John Murray.

Livingstone, David. 1857s. “Missionary Travels Proof Illustrations.” MS. 42432 - MS. 42434. National Library of Scotland. John Murray Archive.

Livingstone, David. 1858. “Letter to John Murray III, 16 February 1858.” MS. 42420, ff. 95r-96r. National Library of Scotland. John Murray Archive.

Murray, John. 1857a. “Letter to David Livingstone, 5 January 1857.” MS. 41912. John Murray’s Letter Book, Mar. 1846 - Apr. 1858. National Library of Scotland. John Murray Archive.

Murray, John. 1857b. “Letter to David Livingstone, 19 January 1857.” MS. 41912. John Murray’s Letter Book, Mar. 1846 - Apr. 1858. National Library of Scotland. John Murray Archive.

Primary Sources Top ⤴

Anon. 1857c. “Livingstone’s African Explorations.” The Monthly Christian Spectator 7: 758–64.

Anon. 1857e. “Reviews.” Athenaeum 1567: 1381.

Anon. 1857g. “Advert.” Notes and Queries 2nd series 102 (December): 483.

Anon. 1858h. “Literary Review.” The United States Democratic Review New Series 42: 79–80.

Anon. 1858i. “Livingstone’s Missionary Travels.” The Dublin University Magazine 51: 56–74.

Anon. 1858k. “Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa.” The North British Review 28: 258–66.

Anon. 1858l. “New York Correspondence.” The Ladies’ Repository: A Monthly Periodical, Devoted to Literature, Arts and Religion 182: 120–22.

Anon. 1858n. “Recent African Exploration.” The Dublin Review 44: 159–80.

Anon. 1858o. “Recent Researches in Africa.” The North American Review 86: 531.

Kane, Elisha Kent. 1856. Arctic Explorations: The Second Grinnell Expedition in Search of Sir John Franklin, 1853, ’54, ’55. Philadelphia: Childs and Peterson.

Livingstone, David. 1861. A Popular Account of Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa. London: John Murray.

Oliphant, Margaret. 1858. “The Missionary Explorer.” Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine 83: 385–401.

Secondary Sources Top ⤴

Blaikie, William Garden. 1880. The Personal Life of David Livingstone. London: John Murray.

Brantlinger, Patrick. 1985. “Victorians and Africans: The Genealogy of the Myth of the Dark Continent.” Critical Inquiry 12 (1): 166–203.

Driver, Felix. 2001. Geography Militant: Cultures of Exploration and Empire. Oxford: Blackwell.

Driver, Felix. 2007. “Missionary Travels: Livingstone, Africa and the Book.” Public Lecture, Great Books on Africa series. Basel: Baslere Afrika Bibliographien.

Helly, Dorothy O. 1987. Livingstone’s Legacy: Horace Waller and Victorian Mythmaking. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press.

Koivunen, Leila. 2001. “Visualizing Africa — Complexities of Illustrating David Livingstone’s Missionary Travels.” Ennen & Nyt. 1: 1-12.

MacKenzie, John M., ed. 1996. David Livingstone and the Victorian Encounter with Africa. London: National Portrait Gallery.

Pettitt, Clare. 2007. Dr. Livingstone, I Presume? Missionaries, Journalists, Explorers & Empire. London: Profile Books.

Contemporary Reviews of Missionary Travels Top ⤴

Note: The following list along with relevant items in the primary sources list, above, provides an indication of how widely Livingstone's book was reviewed in the period immediately after publication.

Anon. 1857a. “Dr Livingstone’s Discoveries in Africa.” Scientific American 12 (20): 155.

Anon. 1857b. “Literary Notices.” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 16 (91): 117–20.

Anon. 1857d. “Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa.” Titan. A Monthly Magazine 25: 727–36.

Anon. 1857f. “‘The African Discoveries of Dr. Livingston’ from the London Examiner.” The Eclectic Magazine of Foreign Literature, Science, and Art, 427–29.

Anon. 1858a. “Article V. Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa.” The Christian Remembrancer, 35.

Anon. 1858b. “Books of the Quarter Suitable for Reading Societies.” The National Review 6: 254–58.

Anon. 1858c. “Critical Notices.” The Southern Presbyterian Review 10: 639.

Anon. 1858d. “‘Dr Livingstone’s Discoveries’ from The Times.” The Southern Literary Messenger; Devoted to Every Department of Literature and the Fine Art 26 (2): 134–47.

Anon. 1858e. “Dr Livingstone’s Travels.” The Scottish Congregational Magazine New Series 8: 9–13.

Anon. 1858f. “Dr Livingstone’s Travels in Africa.” Theological and Literary Journal 10: 636–61.

Anon. 1858j. “Livingstone’s Travels in Africa (from the Spectator).” Littell’s Living Age, New Series, 20: 1–7.

Anon. 1858m. “Notices of New Works.” Southern Literary Messenger; Devoted to Every Department of Literature and the Fine Arts 26 (1): 79–80.

Anon. 1858p. “The Early Life of Dr. Livingstone.” The Quarterly Magazine of the Independent Order of Odd-Fellows, New Series, 1: 309–13.

Anon. 1858m. “Notices of New Works.” Southern Literary Messenger; Devoted to Every Department of Literature and the Fine Arts 26 (1): 79–80.

Anon. 1858p. “The Early Life of Dr. Livingstone.” The Quarterly Magazine of the Independent Order of Odd-Fellows, New Series, 1: 309–13.

Anon. 1858q. “The Farewell to Livingstone Festival.” Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society of London 2: 116–42.

Anon. 1860. “Geographical Discovery in Eastern Africa.” Hunt’s Merchant’s Magazine and Commercial Review 43: 154–66.

Anon. 1862. “A Popular Account of Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa.” Baptist Magazine 54: 176.

Anon. 1863a. “Recent Explorations in Africa.” The Princeton Review 35 (2): 238–90.

Anon. 1863b. “Reviews and Notices, — A Popular Account of Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa.” The Colonial Church Chronicle, and Missionary Journal 1862: 74.

This essay is published by permission of Louise Henderson. Please refer all inquiries and comments to her by email.