Livingstone’s Posthumous Reputation

Cite page (MLA): Livingstone, Justin D. "Livingstone’s Posthumous Reputation." Megan Ward and Adrian S. Wisnicki, eds. Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. University of Maryland Libraries, 2015. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/0bda8609-f62b-4428-9446-3a3307b7ea15.

This essay examines David Livingstone’s posthumous reputation, focusing on his status as an icon of the British Empire. It overviews the numerous biographies that have taken him as their subject and explores the changing ways in which Livingstone was represented as the British Empire developed and declined. This “metabiographical” approach enables us to trace Livingstone’s evolving public image, from the late nineteenth century to the present, as re-written and re-imagined for a range of socio-political purposes.

Introduction Top ⤴

David Livingstone is one of the most written about figures of the nineteenth century. From the 1870s until at least the 1950s, hundreds of books were published that celebrated his life and work in Africa. In light of the sheer volume of attention that Livingstone has attracted, it has become increasingly important not just to study the man, but to study his mythology. No longer is it only Livingstone’s life that is of interest, but rather what has been called his cultural “after-life” (MacKenzie 1996).

This essay investigates Livingstone’s memorialization in print, offering what we might call a brief “metabiography” (Rupke 2008). The purpose of metabiography – or a biography of biographies – is to interrogate the ways in which the historical reputation of a biographical subject is not static but rather can show considerable malleability. Instead of trying to offer the final word about an individual’s “real” identity, it aims to explore “the ideological embeddedness of biographical portraits” (Rupke 2008:215). The aim is thus to offer a broad overview of the ways in which Livingstone has been written and re-written, imagined and re-imagined, across a considerable historical period for a range of socio-political purposes.

Imperial Scramble: The Partition of Africa Top ⤴

Until well into the twentieth century, many of the numerous Livingstone biographies were bound up with the contemporary concerns of the British Empire. That the imperial horizons should manifest themselves in such works is perhaps to be expected, given the considerable impact that Livingstone himself made on British intervention in east and central Africa. Certainly, it is well known that Livingstone’s call for the introduction of Christianity, commerce and civilisation to combat the slave trade proved to be an inspiration for a range of missionary endeavours in Africa.

But what’s of interest here is less the broad influence that Livingstone had, than the specific ways in which various writers put him to use. What emerges in an examination of the numerous biographies is that many of them took Livingstone as their subject in order to explicitly engage with their contemporary imperial moment. As the face of imperialism changed so too did Livingstone’s image: political developments in empire tended to result in the remobilisation and reconstruction of the iconic Livingstone, in accordance with the needs of the immediate context. As John MacKenzie puts it, the Livingstone myth “accommodated itself, or was manifested to fit, the particular requirements of the age” (MacKenzie 1990:33).

In the aftermath of his death, Livingstone’s name acquired particular significance in connection with Nyasaland, where the Church of Scotland and Free Church established mission stations. It is well known that his association with the region, and with the missionary settlements at Livingstonia and Blantyre, formed part of the justification for the establishment of the British Central Africa Protectorate. In the earliest phase of the biographies, then, it became common to authorize such colonial developments using the symbolic weight of Livingstone’s name.

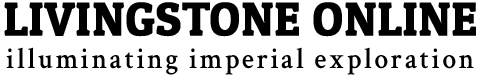

David Livingstone (The Period), 19 February 1870. Copyright Wellcome Library, London. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International |

The first Commissioner of British Central Africa, Sir Harry H. Johnston, did just that in his biography of 1891. For Johnston, Livingstone not only provided the mandate for the protectorate, but was a predecessor to his own political administration in the region: “In Zambezia and Nyasaland especially,” he wrote, “– in what will soon be called ‘British Central Africa’ – Livingstone’s work is rapidly nearing the fruition he longed for under the flag he loved” (Johnston 1891: 367).

This effort to legitimate the Protectorate in this way can be traced in a number of British-published works towards the end of the nineteenth century. It is an argument of this variety, for instance, that we encounter in the abolitionist Horace Waller’s pamphlet of 1887, The Title-Deeds to Nyassa-Land (Helly 1987:325). But other imperial concerns likewise arise in contemporaneous biographies. This is evident in a classic text by Thomas Hughes, an author better known for writing Tom Brown’s Schooldays (1857).

While Hughes was certainly attracted to Livingstone’s muscular Christianity (the ethic of bodily and moral masculinity that Livingstone thought should characterize empire’s servants), a major motivation behind his biography was contemporary colonial competition with Germany. Concerned by the rise of the German East African protectorate, which was “[u]tterly unused” to the work of colonial administration and had “no sympathy for the natives,” he urged his readers to hold fast to “Livingstone’s principles and methods.” The future of east Africa was imperilled and so it was vital, he felt, to remember Britain’s duty in the region “which in God’s providence we have to bear” (Hughes 1889:206).

From this small sampling, we can detect something of the way in which late nineteenth-century Livingstone biographies were embedded in the contemporary politics of the scramble for Africa. Livingstone was mapped onto particular British colonial concerns while, in a more general sense, being interpreted as a forerunner of partition who ushered in a new era for Africa. While he continued to be used to galvanise intervention and defend British interests, however, the way in which Livingstone was represented began to adapt with the dawn of the twentieth century and the accompanying changes in empire.

Edwardian Empire Top ⤴

In the Edwardian period, a mood of imperial anxiety was emerging. A poor performance in the Boer war and increasing competition from international rivals, such as Germany and the United States, presented challenges to British self-confidence. In this context, biographies often recited the achievements and colonial developments since Livingstone’s time in Africa – undoubtedly comforting at a time of unease. They served to encourage their readers that the British Empire was not stagnating.

The new mood, however, articulated itself most clearly on the issue of imperial masculinity (Dawson 1994:148). Concerns about the physical decline of British troops, mounting challenges to established social norms, and developing fears about social degeneration, coalesced into a general anxiety about the malaise of British manhood.

Of course, as a representative of muscular Christianity Livingstone had long been valorised as an archetype of manliness. But in the Edwardian period, he was used even more explicitly to articulate a more vigorous and physical masculinity. One contemporary response to the crisis was to lay a new emphasis on the importance of “physical hardship” and fitness (Jones 2003:250), and so Livingstone’s biographers increasingly stressed his impressive fortitude and bodily capabilities.

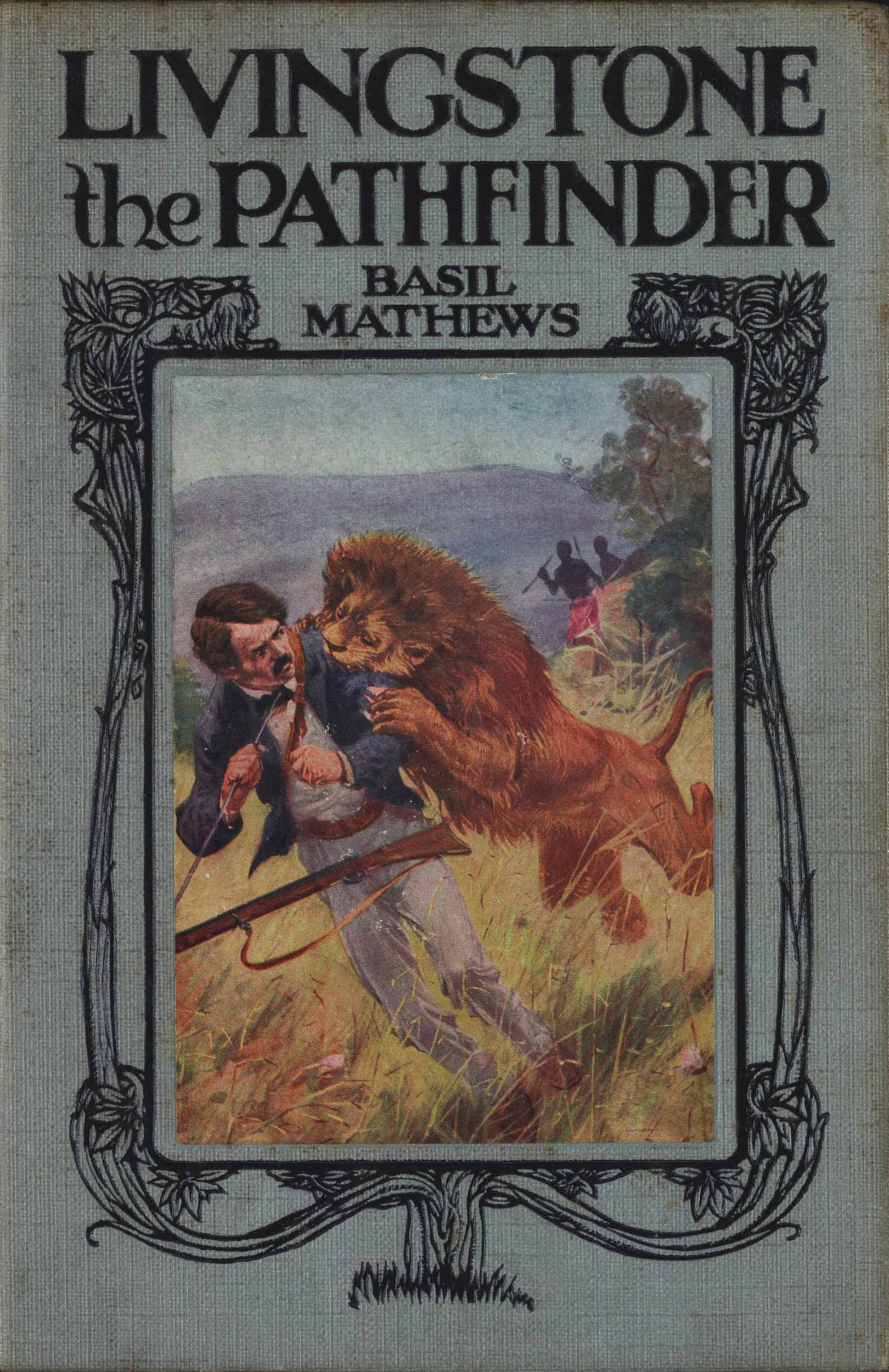

Arthur Lincoln, for example, celebrated Livingstone’s “hard labour” and “Spartan training,” which had the effect of “inuring his body to hardship and privation” (Lincoln 1907:8). Likewise, in one of the bestselling biographies, Livingstone the Pathfinder, by London Missionary Society editor Basil Mathews, Livingstone appeared as a “hero-scout,” undeterred by “blistering plain and tangled forest,” defying “beast, savage men, marsh, forest, fever” (Mathews 1912:6, 108, 86).

Livingstone the Pathfinder (Cover), 1912, by Basil Matthews and Earnest Prater. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland |

Such authors, moreover, sought to address the crisis in British imperial masculinity by holding Livingstone up as an exemplary life and by directing their books towards younger readers. In Mathews’ case, we should also note the significance of repeatedly describing Livingstone as a “scout”; this made a direct connection to Baden Powell’s recent popular movement which, with its emphasis on physical reinvigoration and moral improvement, was itself a response to Edwardian anxieties about national health and imperial wellbeing (Boehmer 2004:xii).

Post-war Trusteeship Top ⤴

While the tremendous suffering of the First World War struck a major blow to nineteenth-century heroic ideals, Livingstone’s reputation continued to flourish in the aftermath. It has been suggested that while military heroes were more difficult to lionise in the climate of post-war disillusionment, explorers like Livingstone and Robert Falcon Scott were able to provide a more amenable “epic of heroism for a generation tired of war” (Jones 2003:269). Yet, at the same time, the process of re-adaptation continued as the empire entered a new period and as imperialism was reformulated for a changing world.

Livingstone, the Liberator. Copyright Livingstone Online (Gary Li, photographer). May not be reproduced without the express written consent of the National Trust for Scotland, on behalf of the Scottish National Memorial to David Livingstone Trust (David Livingstone Centre).

In the 1920s, “trusteeship” became increasingly important in international discourse. While the idea had a long intellectual heritage, it developed in prominence in conjunction with the mandates system established by the League of Nations. The governing principle was that non-European territories were to be administered in “trust,” with the duty of developing the country to the benefit of its citizens (Bain 2003:99). As this concept was more explicitly articulated in British policy, Livingstone’s biographers made efforts to connect it to him.

For instance, the missionary writer W. P. Livingstone described “the mandate system” as essentially established on “Livingstone’s principle”: both shared the view, he felt, that “the well-being and development of native peoples form a sacred trust of civilization” (Livingstone 1929:124). The major biography of the period, by Reginald J. Campbell, similarly projected Livingstone as the architect of the present system: “it may with truth be said that it was chiefly he who made possible the moral trusteeship of the advanced over the backward races which is now a principle of the League of Nations [...] The British imperial Government has frankly admitted and applied the principle of trusteeship to all its dealings […] this was Livingstone’s vision” (Campbell 1929:20).

Imperial Decline Top ⤴

Shifts in imperial mentality continued to manifest themselves in the Livingstone works of the mid-twentieth century. The major book of the 1940s was undoubtedly Livingstone’s Last Journey by the celebrated Reginald Coupland, Beit Chair of Colonial History at Oxford. While the book is an impressive scholarly achievement, its significance here is the way in which it responded to the growing sense of imperial decline that was developing at the close of the Second World War. If the discipline of British imperial history, in its early and mid-twentieth century form, has sometimes been described as a “patriotic enterprise” that served to defend “contemporary British expansion,” this is certainly illustrated in the case of Coupland (Drayton 2011:675). He has been identified as an imperial apologist, who was confident in the moral authority and justice of British rule.

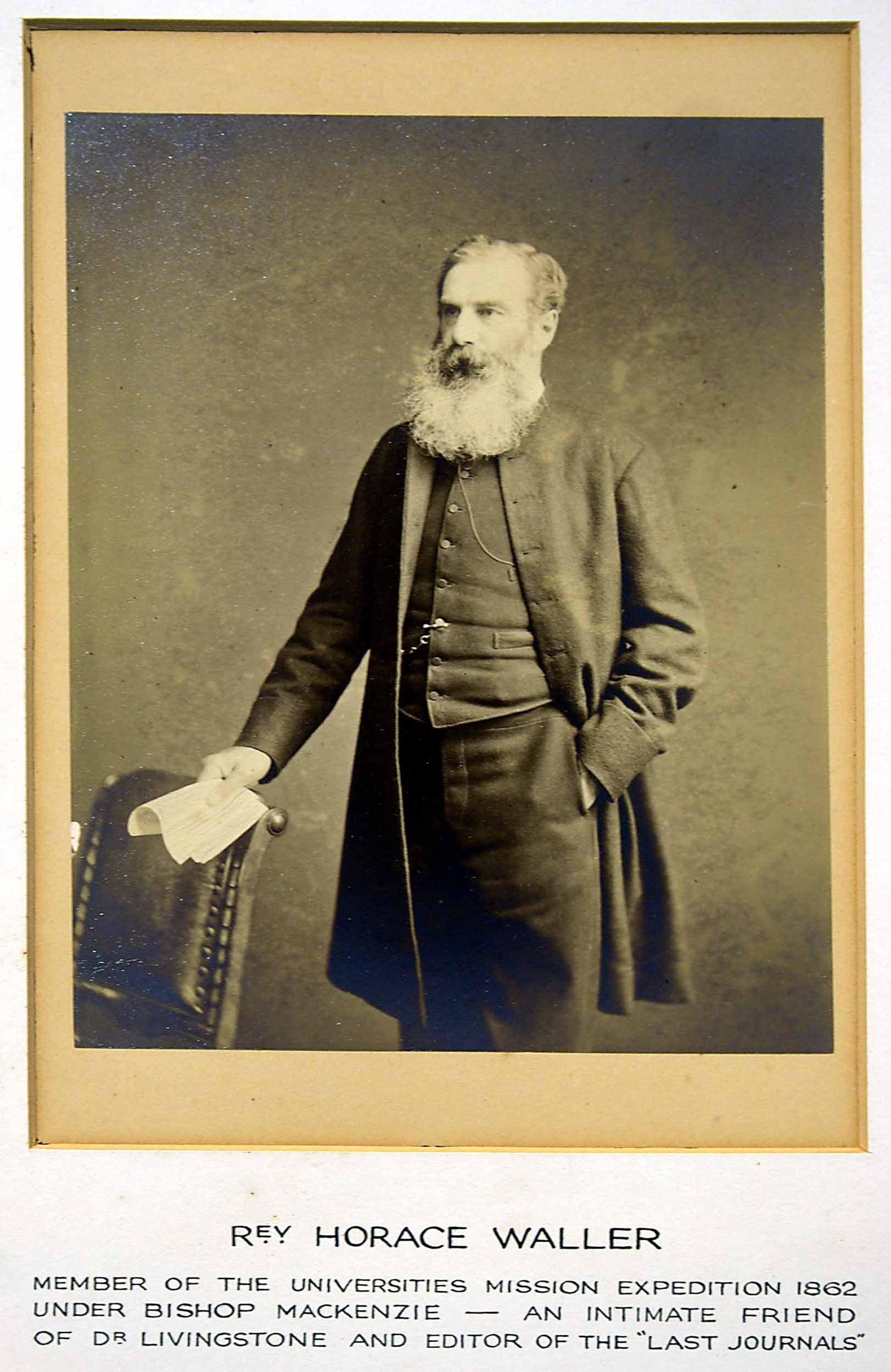

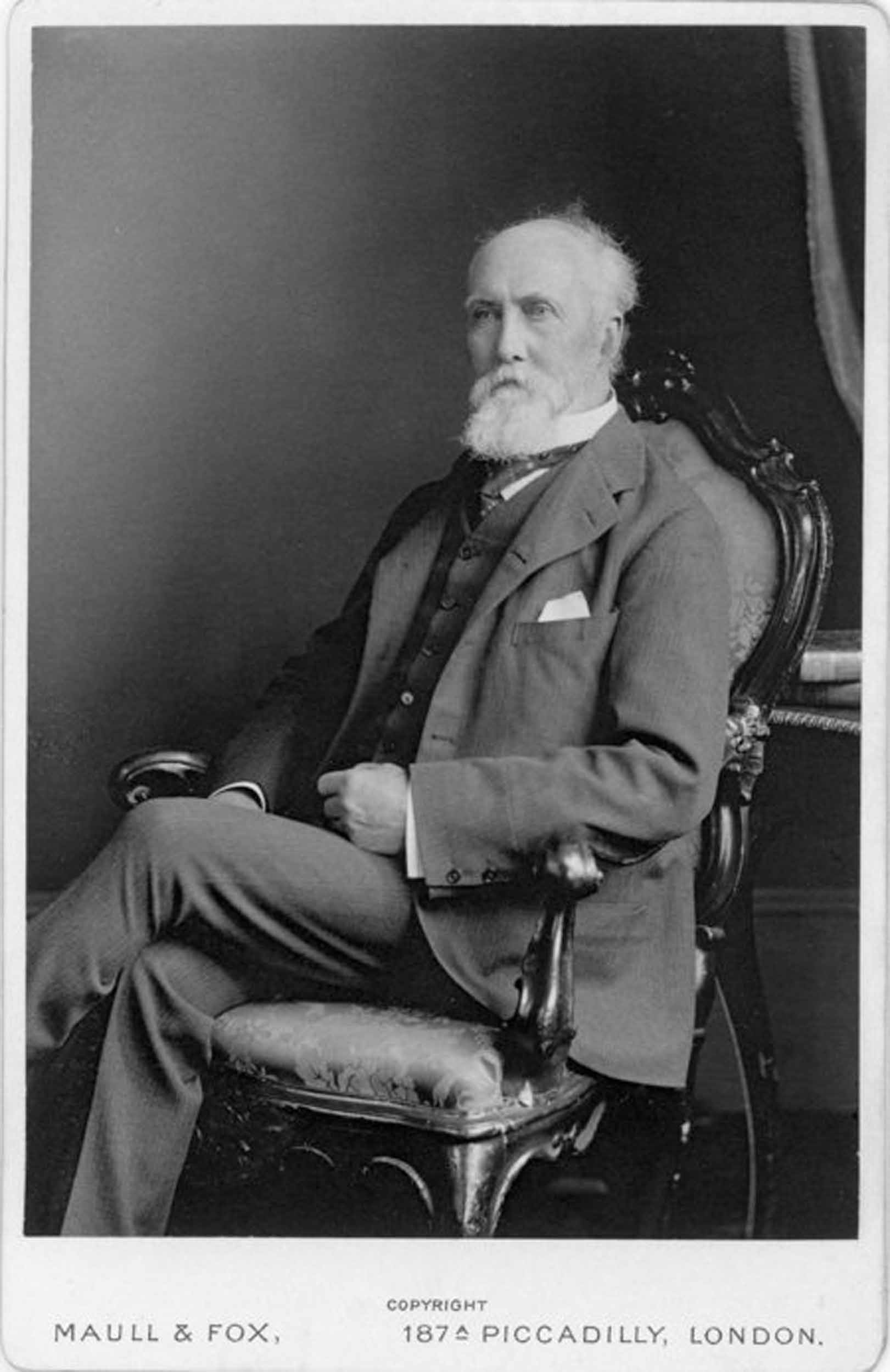

Indeed, Livingstone’s Last Journey was part of Coupland’s effort to interpret the imperial past as a humanitarian endeavour. The book dwells not only on Livingstone, but focuses on revealing what he contends was a crucial abolitionist network, a “triple alliance,” battling the Arab slave trade: “Livingstone, its spearhead, penetrating the black veil […] Kirk, his tried and trusted Lieutenant […] Waller […] with his hand on all the strings of the humanitarian movement” (Coupland 1945:32). It ends by celebrating the consummation of their efforts, when the treaties between Britain and Zanzibar in the 1870s struck a “mortal blow” to the slave trade. It was a striking “historical coincidence,” he suggested, that on the very day Livingstone died “the first blow was struck in a campaign which in three short years brought to its final triumph the cause to which he had given his life” (Coupland 1945:254).

Coupland’s celebratory history and his emphasis on Britain’s humanitarian intervention in global affairs must be read in the context of the United Kingdom’s diminishing world role and developing challenges to the empire. With Britain’s weakened position and with the growth of nationalist movements in the wake of the Second World War, it was recognized that the country needed to “set aside sentimental imperialism and take a realist view of our problems” (Clement Attlee, qtd. in Hyam 2006:94). Yet at an important juncture in imperial affairs, Coupland continued to valorize the past and perpetuate a narrative of heroic history. His book was a conservative effort in the face of political change, an attempt to inspire faith in imperialism at a moment when the British Empire was declining and anti-colonialism was on the rise.

| (Left) Photograph of Horace Waller. Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Object images used by permission. May not be reproduced without the express written consent of the National Trust for Scotland, on behalf of the Scottish National Memorial to David Livingstone Trust (David Livingstone Centre). Right) Photograph of John Kirk. Copyright Royal Geographical Society (with IBG). Used by permission for academic purposes only. For non-academic use permission, please contact the Picture Library. |

Partnership and the Central African Federation Top ⤴

Although British imperialism suffered a major blow in the Second World War, the end of empire was not immediate. While the Labour Party could declare in the late 1940s that “Imperialism is dead,” it could also claim that “the Empire has been given new life” (qtd. in Howe 1993:144). It was perceived that important work still remained for the British power to engage in, even in the changed context of the post-war world.

The concepts of “political advancement” and “partnership” were developed, as alternatives to the now questionable “imperialism” of the past. In some ways, “partnership” belonged in the tradition of imperial trusteeship (Bain 2003:116), but it represented a move away from paternalism and a greater emphasis on collaboration. It also implied more scope for colonial territories to eventually achieve self-government. At the same time, of course, it was a necessary reconceptualization of colonial relationships in the midst of the empire’s decline.

While Coupland had recited the heroic story of Livingstone and the abolitionist “triple alliance” to counter imperial disenchantment, others engaged in the familiar pattern of remoulding Livingstone according to the now established creed. In 1957, for instance, Cecil Northcott wrote that “the growth of the idea of partnership between the races,” was “truly Livingstonian.” For him, “the gradual advancement of Africans into positions of authority in government and industry” directly followed what he called “The Livingstone Tradition” (Northcott 1957:79).

Lantern Slides of the Life, Adventures, and Work of David Livingstone. Courtesy of the Smithsonian Libraries, Washington, D.C. |

At the same time, Northcott gave Livingstone more direct political significance, applying him to a recent political formation in central Africa. The “intangible fields of ‘goodwill,’” he wrote, resulting from Livingstone’s travels, were sure to be “a practical asset, particularly on the life of the Federation” (Northcott 1957:77). Here, Northcott was referring to the Central African Federation, a controversial state that came into being in the 1950s and which united Nyasaland and both Southern and Northern Rhodesia. While European settlers had lobbied for this, it faced considerable opposition from Nyasaland’s black communities, who feared the influence of Southern Rhodesia’s “parallel development” policy.

Although the Federation was short lived, Northcott was not alone in casting Livingstone as its founder. For Michael Gelfand, historian and Professor of Medicine at the University of Rhodesia, Livingstone “was the driving force which led other men […] to seek the Central African field.” In Gelfand’s opinion, it was “not hard to see that the birth of the new Federation of Central Africa owes its existence to this early influence” (Gelfand 1957:13-14).

Gelfand’s scholarly interest lay in Livingstone’s medical contributions, but he was also clear that the explorer’s immediate relevance to the new federal state had motivated his biography: “Never has it been more necessary than at the present time in the history of Rhodesia and Nyasaland that we should try to understand the origins of this new state, for once we understand its beginning, we can prepare ourselves for the best way in which to ensure its welfare” (Gelfand 1957:xii).

Decolonisation and Critical Biography Top ⤴

Decolonisation ended the use of Livingstone on behalf of the projects of empire and, instead, brought a more sceptical eye to his life and posthumous reputation. Perhaps because of his political utility, Livingstone seems to have avoided critical biography until the 1970s: he was spared the debunking to which so many other heroic figures of the nineteenth century had been subject, from Lytton Strachey’s Eminent Victorians (1918) onwards.

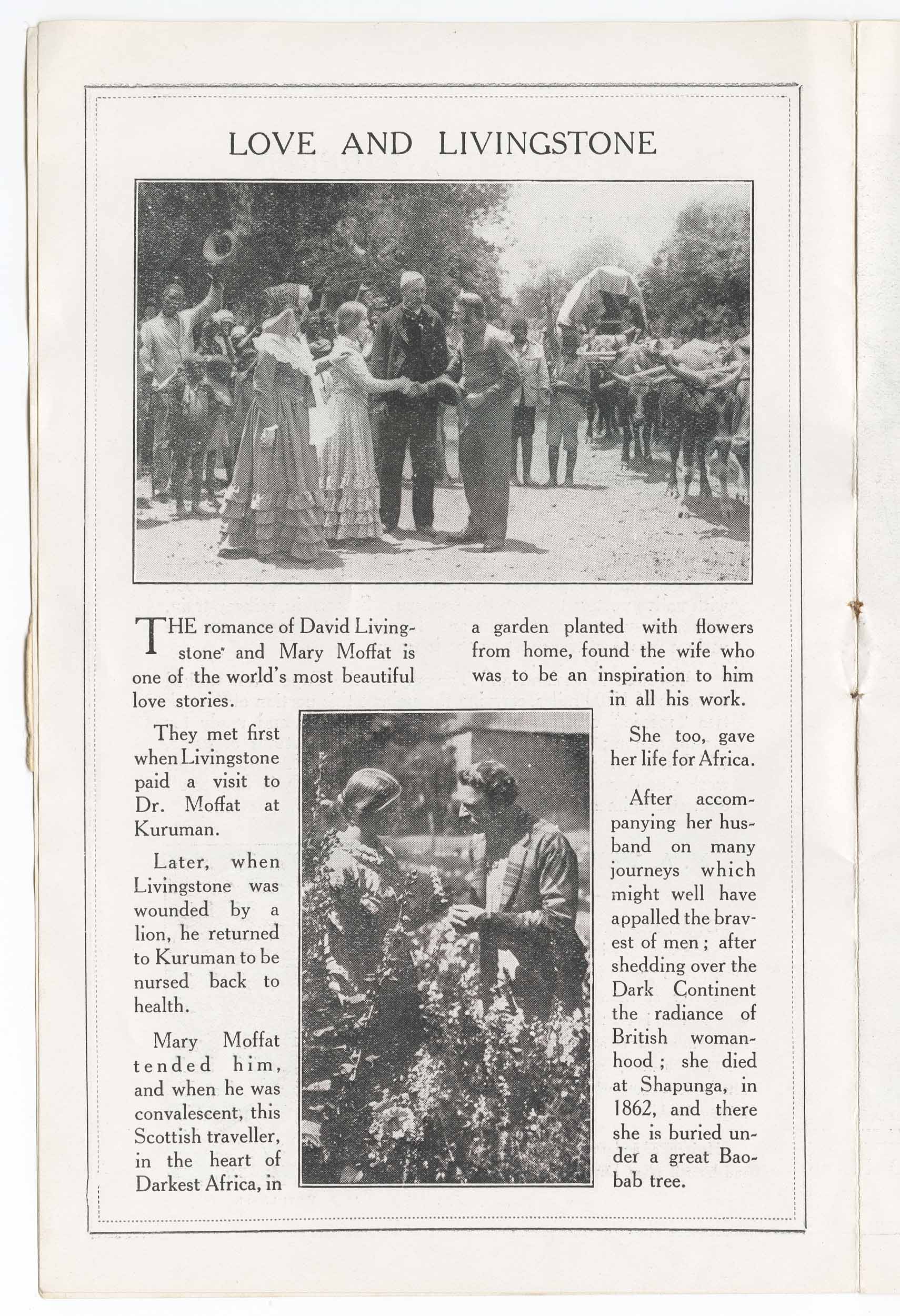

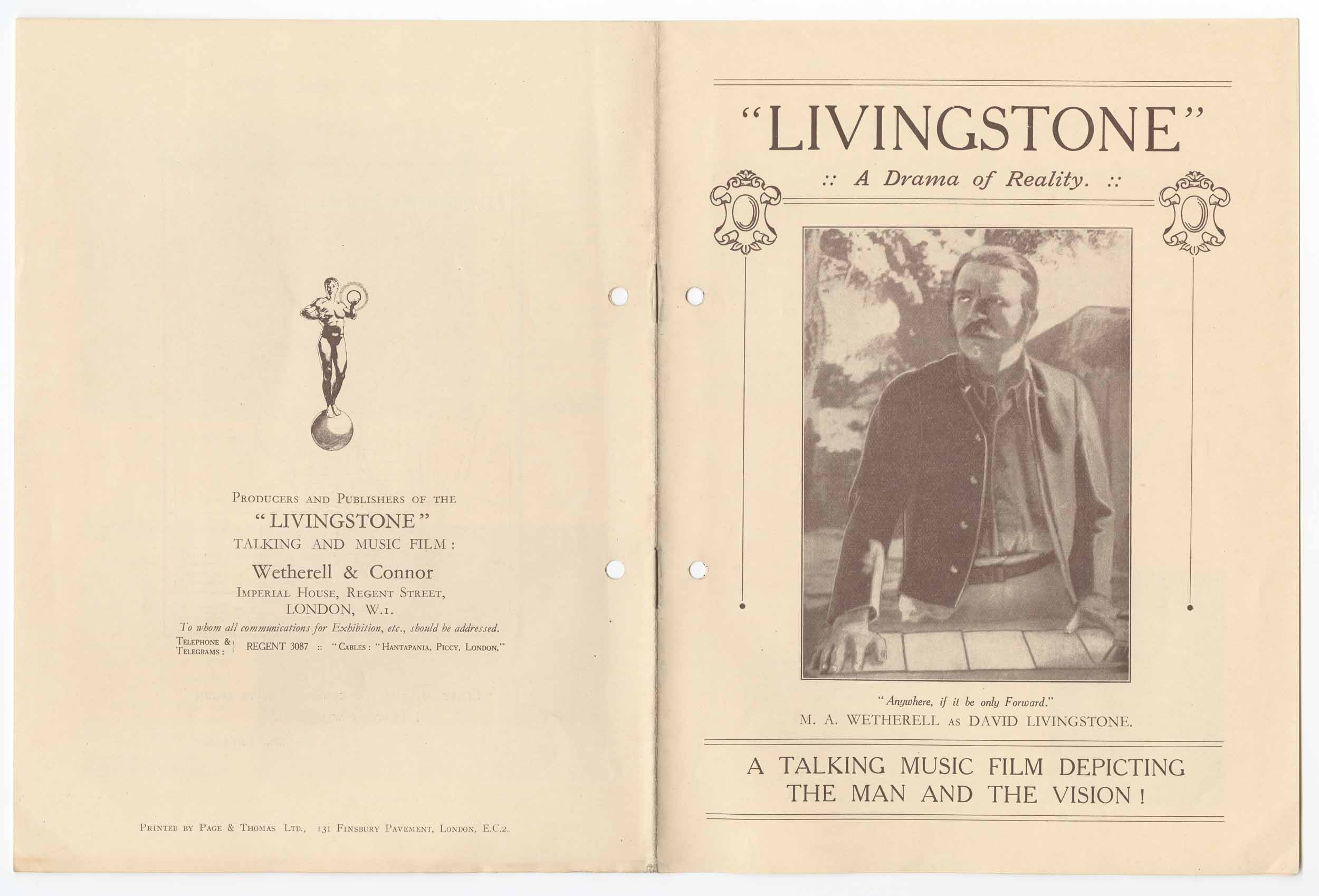

Promotional Booklet for Livingstone: A Drama of Reality (Film), 1925. It was this sort of idealistic representation that critical biographers rejected. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland |

With the political shifts in mentality that accompanied the end of empire, the saintly image of Livingstone began to be dismantled. George Martelli, for instance, aimed to part ways with “hero-worshippers” by writing a book “free of the excessive adulation which has characterised its predecessors” (Martelli 1970:ix). What emerged was a picture of a man of “imaginative enterprise, grit,” yet simultaneously “authoritarian and secretive” (Martelli 1970:242, x).

The critical approach was taken further by Judith Listowel, as well as by the most celebrated biography of Livingstone by Tim Jeal. While Jeal’s perspective – which he describes in his expanded bicentenary edition as a “revised orthodoxy” (Jeal 2013:xii) – was undoubtedly the result of rigorous research, it was also an approach fostered by the contemporary political and intellectual environment.

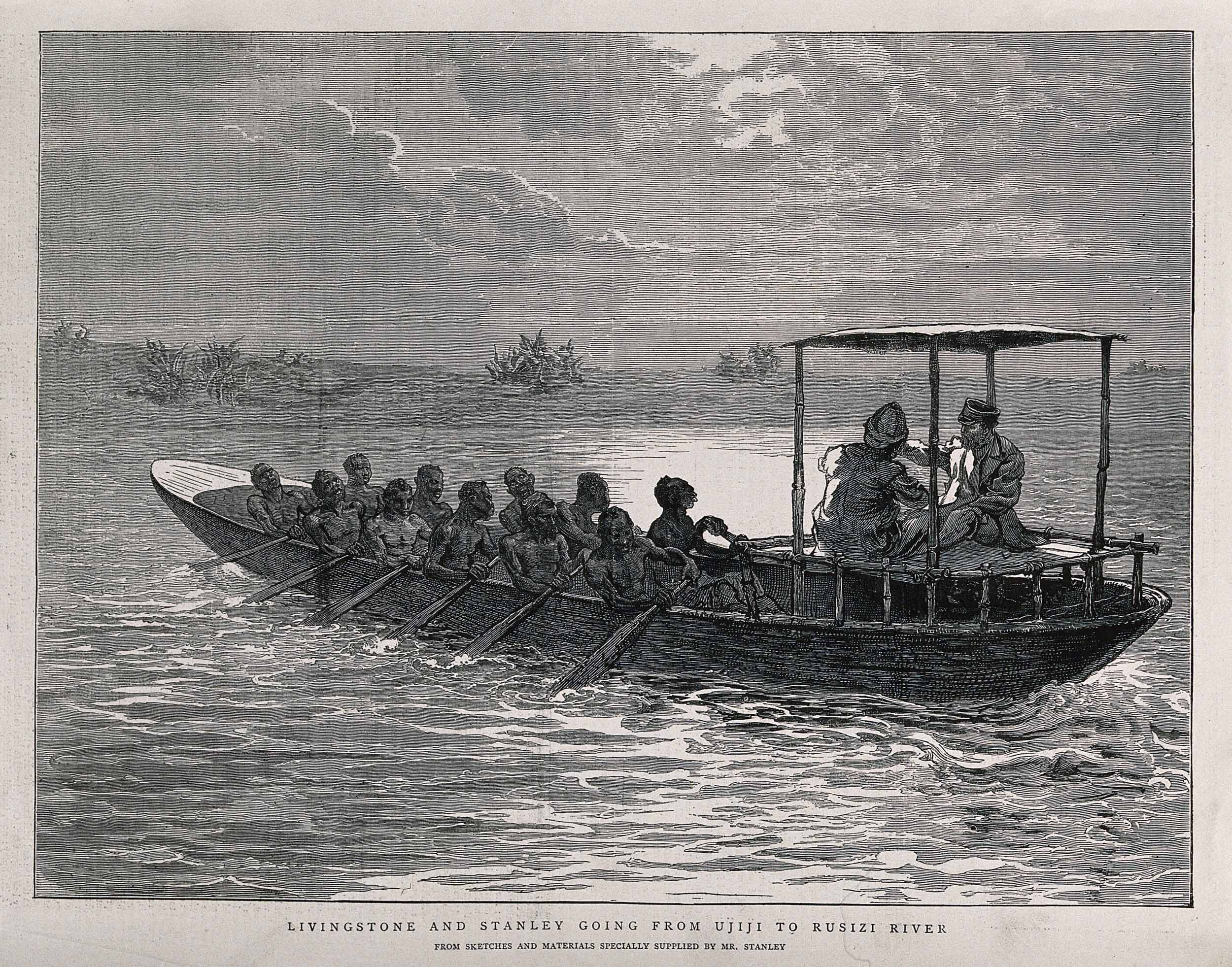

"Livingstone and Stanley going from Ujiji to Rusizi River." Copyright Wellcome Library, London. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

Jeal’s revisionism aimed to rebut long-established notions about one of Britain’s cherished heroes. While Livingstone may indeed have been “a great man,” he now appeared as “awkward, sullen,” “intolerant, narrow and self-opinionated” (Jeal 2001:371, 20, 25). Certainly, Livingstone was “courageous and resilient”, but this “did not make him likeable” (Jeal 2001:25). For Jeal, Livingstone was one of those who saw “his own wishes and personal preferences in terms of the dictates of Providence” (Jeal 2001:108). Motivated by ambition and not least by ego, “[t]he important thing was that he should lead and others follow” (Jeal 2001:108).

Although Jeal’s approach enlarged and productively challenged prevailing conceptions of the celebrated missionary and explorer, its conditions of possibility lay in the decolonisation of the 1960s and the end of Britain’s imperial age. Now, in a changing cultural climate, Livingstone was more open to critical reappraisal than he had been in the past: the time was ripe to deflate and debunk one of the empire’s established icons.

Postcolonial Rewriting Top ⤴

If the end of empire contributed to biographical reinterpretation, it is also worth noting that this period gave rise to creative literature that took Livingstone as its subject. Since there are very few fictional texts that engaged with Livingstone prior to the second half of the twentieth century, this form of rewriting seems primarily indebted to the rise of the postcolonial movement. Broadly speaking, postcolonial criticism has aimed to reconsider the history of colonialism “from the perspectives of those who suffered its effects” (Young 2001:4). It is a committed critique, closely connected with the anti-colonial and nationalist struggles prior to decolonisation.

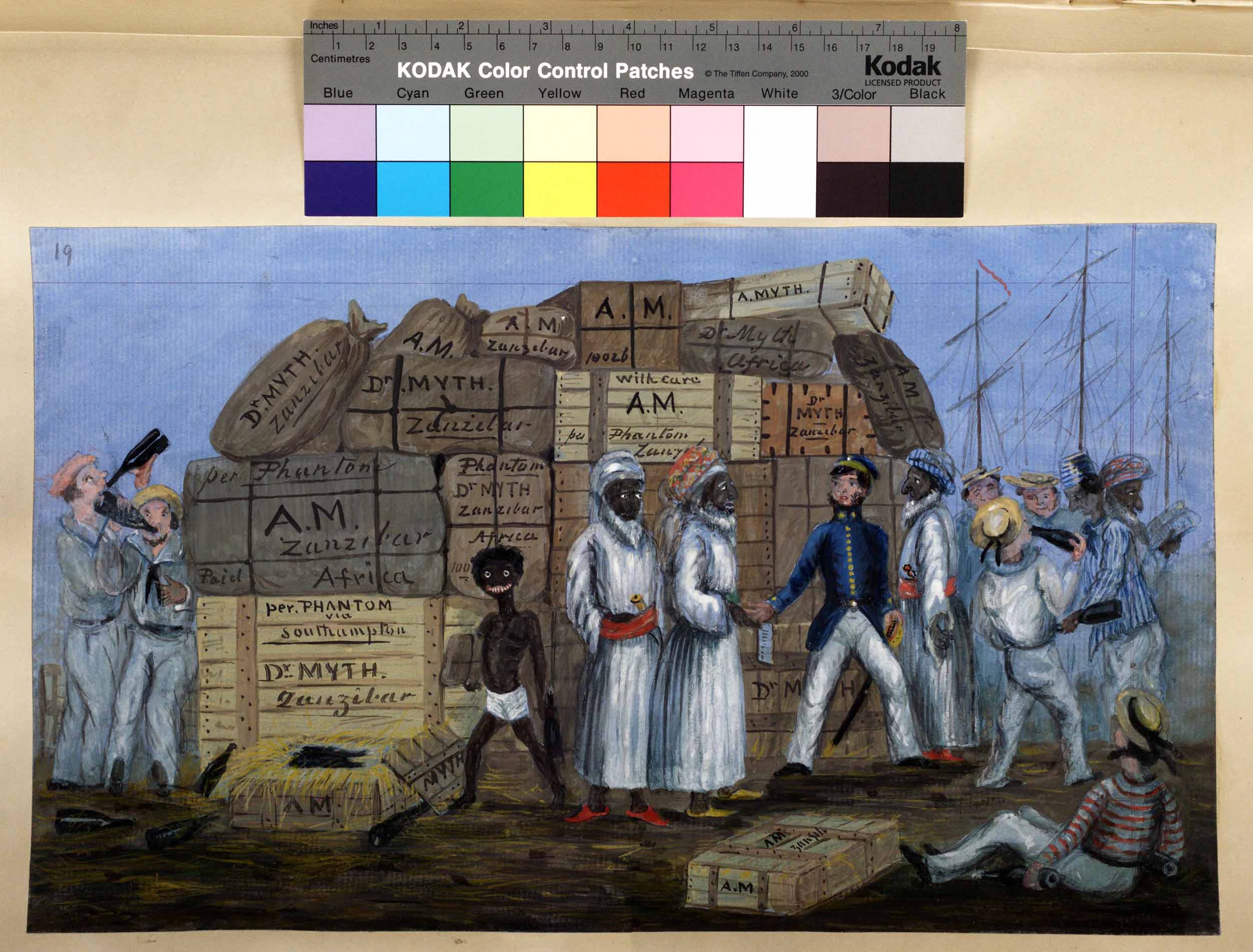

Scenes in Hot Latitudes and Travels in Search of the Wishi Washi to its Junction with the Puddi Muddi. This complex image, dating from the 1880s, engages in crude racial caricature while also aiming to satirise Livingstone and the European presence in Africa. It is included here to illustrate the historical stereotypes that postcolonialism would contest and critique. Courtesy of the Smithsonian Libraries, Washington, D.C.

It also emphasises the relationship between culture and politics, pointing to the importance that “cultural representations” played within the colonial project (Boehmer 1995:5). Resisting colonialism was thus not only about seeking political freedom, but about emancipating the consciousness and rejecting the cultural values that colonialism imposed. Much postcolonial literature then has taken an oppositional stance towards the former imperial metropole, contesting and deconstructing colonial ideology.

As an established hero of empire, Livingstone was caught up in this project. For instance, in her fictional travelogue, Looking for Livingstone, Canadian-Caribbean author Marlene NourbeSe Philip aims to confront the European myth of “discovery.” By recounting the journey of a nameless female “Traveller,” pursuing “Dr Livingstone,” Philip’s prose-poem responds to the familiar narrative of exploration: here, however, Livingstone is the object rather than the agent of discovery.

For Philip, European exploration was really a form of appropriation, dependent on the knowledge of local peoples. When the Traveller and Livingstone finally meet she rebuts his claim to discovery, stripping him of credit: “You’re nothing but a cheat and a liar, Livingstone-I-presume. Without the African,” she exclaims, “you couldn’t have done anything” (Philip 1991:62).

"Livingstone Attacked by the Lion." Copyright Wellcome Library, London. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

For the Traveller, moreover, exploration was a form of conquest. Livingstone and “all those other explorers” operated under the logic of “Discover and possess – one and the same thing. And destroy” (Philip 1991:15). In her effort to rewrite history – which she describes as “like talking to Livingstone and telling him a few things” – Philip both satirises Livingstone and subjects him to imaginative violence (Carey 1991:19).

There is much more to say about the complex thematics of this novel, but the point to note here is that Philip’s iconoclasm is connected to Livingstone’s prior history as a symbol of the colonial past: it is his iconic value which enables him to serve as a focal point of her critical imperative.

Philip is not alone in her approach. For instance, Lennart Hagerfors’s novel The Whales in Lake Tanganyika narrates Stanley’s journey in pursuit of Livingstone from the perspective of one of the expedition members, John William Shaw. When Stanley – envisaged here as sadistic and deranged – finally finds Livingstone, we are met with an image that conspicuously departs from heroic characterisation. Livingstone looks “like an injured bird that couldn’t fly”: with his “apelike arms” and “skinny and bowed legs,” we are told, he “resembled a chimpanzee” (Hagerfors 1991:163).

To some extent, the aim here is to reduce Livingstone’s stature and subject him to scorn. By laughing at Livingstone, Hagerfors reacts against heroic history and deflates European pride in the colonial and civilising mission. Yet the implication is also that Livingstone has been transformed by his experience: rather than colonising Africa, it has colonised him.

This is not to say that Hagerfors is casting Africa as a space of degeneration or relying on the familiar trope of “going native.” Instead, Livingstone’s decline suggests the breakdown of values that no longer hold; he has been chastened, domesticated, reduced by his experience. He is alienated from his “native tongue,” which now “sounds frightful,” while talk of Europe fills him with “terror” (Hagerfors 1991:168, 170). The European assumptions brought him to Africa have been vanquished and he now listens instead of preaching. Where once Livingstone had possessed the confidence to speak with “a mouth as large as a cathedral,” now “all that remains of [him] is an ear” (Hagerfors 1991:168).

With their commitment to postcolonial revision, Philip and Hagerfors take Livingstone and rewrite him for political purposes. Other authors have engaged in similar projects. For instance, in his play, Livingstone and Sechele, David Pownall imagines the missionary’s interactions with his convert Sechele, in order to offer reflections on the complex interaction between Christianity and colonialism.

Such works are generally less interested in interrogating Livingstone as an historical subject than in responding to his status as an iconic figure of the imperial past. But while these representations do not primarily aim for historical accuracy, they demonstrate clearly the malleability of the historical life and the impact of socio-political commitments on interpretation. For these authors, oriented in opposition to imperialism, Livingstone took on new meanings.

It is worth noting that other creative writers have put Livingstone to different use. In a play entitled The Last Journey, South African author and political activist Alan Paton retold the story of the porters who transported Livingstone’s body to the coast after his death, as an African epic. Written in the context of escalating racial segregation, the play’s purpose was to oppose the apartheid system. Similarly, again writing from an apartheid context, Nadine Gordimer drew on passages from Livingstone’s journals in order to offer critique of white racism in her short story, “Livingstone’s Companions.”

Livingstone on Screen Top ⤴

In this essay I have focused on biography, followed by a brief foray into fiction and drama. Yet Livingstone has been commemorated in other forms too. His death in 1873, for instance, inspired a profusion of elegiac poetry expressing a sense of loss and public grief (Livingstone 2012; Livingstone 2014). Livingstone has also been depicted on the big screen. Marmaduke Arundel Wetherell’s 1925 film is perhaps the most interesting British production. Shot in various African locations that Livingstone had himself visited, the final footage contained striking scenes of landscape and wildlife.

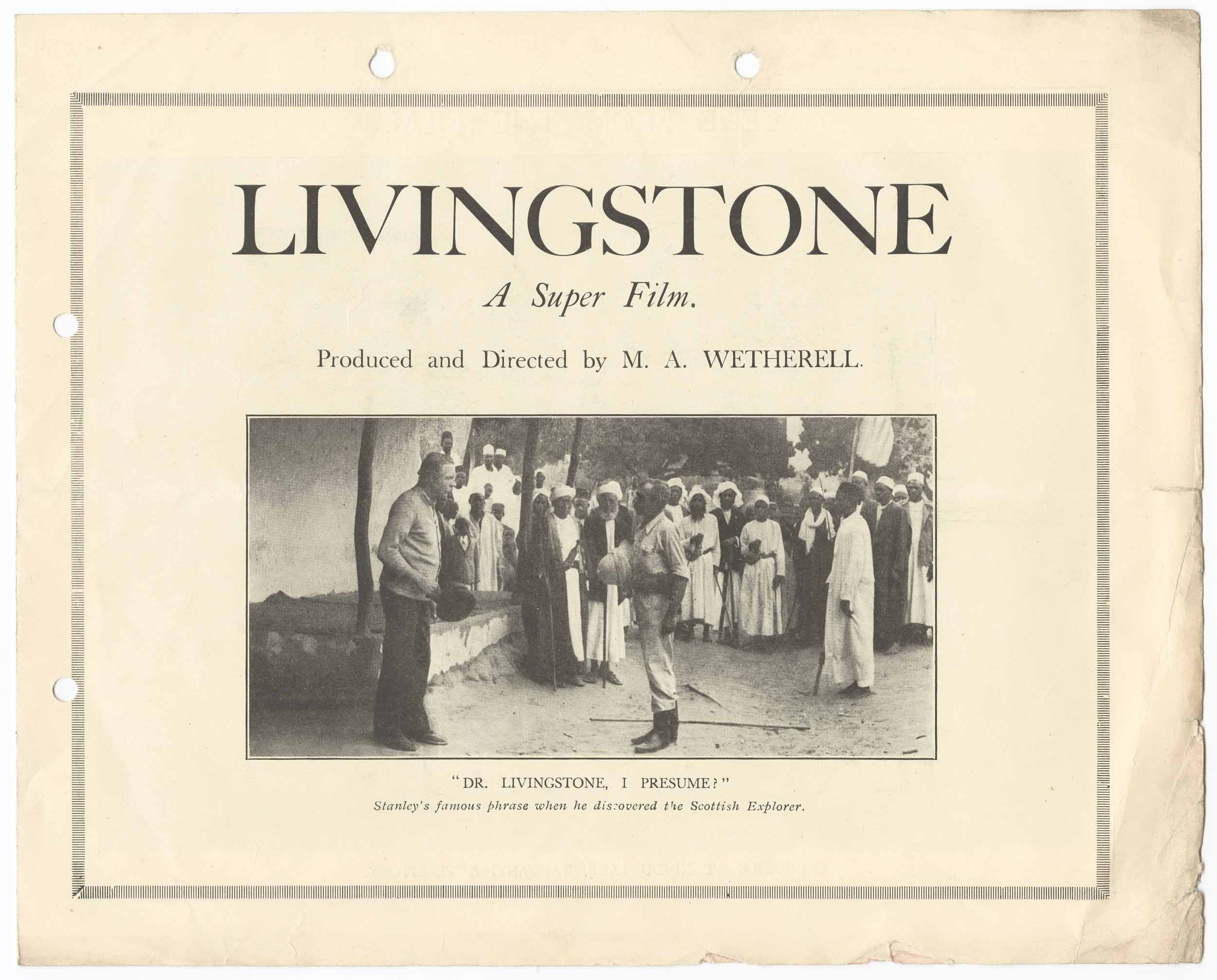

Promotional Leaflet for Livingstone: A Super Film (Film), 1925, by Hero Films Ltd. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland

While the movie presented a conventional narrative of Livingstone’s life, the producers had particular purposes in mind in staging his story on screen. From the initial plans to the later publicity the film received, it is clear that it was motivated by concerns over the dubious moral and cultural influence of Hollywood flicks. This “all British masterpiece” was intended to inspire patriotic and imperial sentiment, and to provide a wholesome alternative to the influx of American films increasingly dominating British cinema (Rapp and Weber 1989:8, 3).

Hollywood, however, decided to take up the Livingstone story as well and in 1939, 20th Century Fox released its own blockbuster. Starring big names like Spencer Tracy and Cedric Hardwicke, this production focused on Stanley’s quest to find Livingstone. Contrasting Stanley’s American vigor with the torpor of the various British characters, the film implies that the older custodians of civilisation are in need of rejuvenation by a younger more energetic nation.

Promotional Booklet for Livingstone: A Drama of Reality (Film), 1925, by Hero Films Ltd. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland

At the end, when Stanley adopts Livingstone’s mantle and sets out on new African adventures – to the soundtrack of “Onward Christian Soldiers” – the film emphasises the joint work of Britain and America in upholding Christian civilisation (Pettitt 2007:122). Released just prior to the outbreak of the Second World War, this message of a shared transatlantic vision undoubtedly appeared at an important political juncture.

Conclusion Top ⤴

This essay has offered a brief overview of Livingstone’s evolving literary legacy. Adopting a metabiograpical approach and focusing on imperial contexts, it has demonstrated the ways in which he has been represented and put to work for particular political purposes. There are other strands of Livingstone’s posthumous reputation that are also worthy of attention – for instance, the relationship it bore to changing Scottish and British national identities (Livingstone 2014). And while the approach here has been primarily textual, there is scope for future research on other means of remembrance. For instance, Livingstone has been extensively commemorated in monumental form, with statues appearing in Edinburgh in 1876 and Glasgow in 1879, and a memorial church in Blantyre in 1877.

Here, however, we have traced the ways in which Livingstone has been remoulded according to the changing ideological needs of empire, from the height of late Victorian imperialism to the period of colonial decline and beyond. The outline that I’ve offered, it should be acknowledged, does not do full justice to the range of representations of Livingstone that can be detected at any one historical moment. Rather than being simply mapped onto a political context, Livingstone was constructed in dialogue with it.

Nevertheless, the aim here has been to delineate broad patterns, to identify political shifts that conspicuously transfigured the way that biographers approached his life and his contemporary relevance. To the Victorians, Livingstone was a pioneer of partition; to the Edwardians, a model of imperial manliness; following World War One, he was seen as the inspiration behind trusteeship, and later as the pioneer of partnership and the Central African Federation.

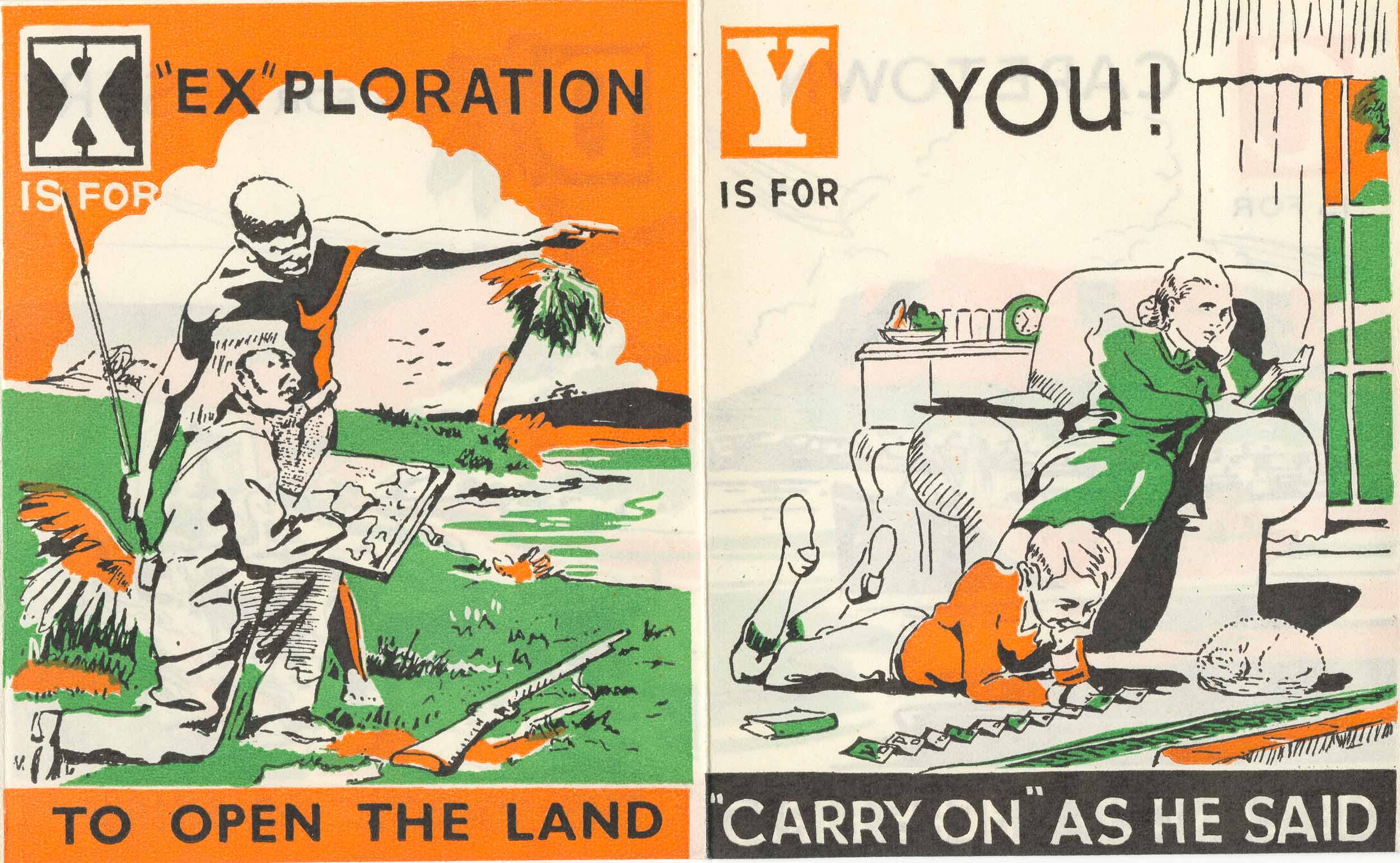

Alphabetical Adventures of Livingstone in Africa for Boys and Girls, detail (The Livingstone Press, London), 1941, by S.E. Iredale. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland

Following decolonisation and the discrediting of empire, the way was clear for more hostile revision and Livingstone soon began to appear in less heroic guise. Extending the metabiographical method to include creative literature opens the parameters to texts that pressed the critical approach further and that directly responded to his imperial legacy: written from a committed postcolonial perspective, with its politico-intellectual orientation, these works set out to critique one of the British Empire’s foremost icons.

Livingstone’s ‘afterlife’ of course remains ongoing: the posthumous reputation of an historical subject is perhaps never a finished business. As political and cultural contexts continue to evolve, David Livingstone will doubtless continue to be re-visited, re-written and re-constructed.

Acknowledgements Top ⤴

This essay is based on my monograph-length study of Livingstone’s reputation, Livingstone’s “Lives”: A Metabiography of a Victorian Icon (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2014), particularly chapters 4 and 6. This research is presented here in abbreviated form with the kind permission of the publisher, Manchester University Press.

Works Cited Top ⤴

Bain, William. 2003. Between Anarchy and Society: Trusteeship and the Obligations of Power. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Boehmer, Elleke. 1995. Colonial and Postcolonial Literature: Migrant Metaphors. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Boehmer, Elleke. 2004. “Introduction.” In Scouting for Boys, edited by Elleke Boehmer, xi – xxxix. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Campbell, R.J. 1929. Livingstone. London: Ernest Benn Ltd.

Carey, Barbara. 1991. “Secrecy and Silence: Marlene Nourbese Philip’s Struggle to Connect with Her Lost Cultural Heritage Fuels Her Writing.” Books in Canada 20 (6): 17–22.

Coupland, Reginald. 1945. Livingstone’s Last Journey. London: Collins.

Dawson, Graham. 1994. Soldier Heroes: British Adventure, Empire and the Imagining of Masculinities. London: Routledge.

Drayton, Richard. 2011. “Where Does the World Historian Write From? Objectivity, Moral Conscience and the Past and Present of Imperialism.” Journal of Contemporary History 46 (3): 671–85.

Gelfand, Michael. 1957. Livingstone the Doctor; His Life and Travels: A Study in Medical History. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Gordimer, Nadine. 1972. “Livingstone’s Companions.” In Livingstone’s Companions, 3–37. London: Jonathan Cape.

Hagerfors, Lennart. 1991. The Whales in Lake Tanganyika. London: Penguin.

Helly, Dorothy O. 1987. Livingstone’s Legacy: Horace Waller and Victorian Mythmaking. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press.

Howe, Stephen. 1993. Anticolonialism in British Politics: The Left and the End of Empire, 1918–1964. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Hyam, Ronald. 2006. Britain’s Declining Empire: The Road to Decolonisation, 1918–1968. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jeal, Tim. 2001. Livingstone. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Jeal, Tim. 2013. Livingstone: Revised and Expanded Edition. New Haven, CT; London: Yale University Press.

Johnston, H.H. 1912. Livingstone and the Exploration of Central Africa. London: George Philip & Son Ltd.

Jones, Max. 2003. The Last Great Quest: Captain Scott’s Antarctic Sacrifice. Oxford: Blackwell.

King, Henry, and Otto Brower. 1939. Stanley and Livingstone. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation.

Lincoln, Arthur. 1907. David Livingstone: Missionary, Explorer, and Philanthropist. London: A. Melrose.

Listowel, Judith. 1974. The Other Livingstone. Lewes, Sussex: Julian Friedmann Publishers Ltd.

Livingstone, Justin D. 2012. “A ‘Body’ of Evidence: The Posthumous Presentation of David Livingstone.” Victorian Literature and Culture 40 (1): 1–24.

Livingstone, Justin D. 2014. Livingstone’s “Lives”: A Metabiography of a Victorian Icon. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Livingstone, William Pringle. 1929. Story of David Livingstone. London: Livingstone.

MacKenzie, John M. 1990. “David Livingstone: The Construction of the Myth.” In Sermons and Battle Hymns: Protestant Popular Culture in Modern Scotland, edited by Graham Walker and Tom Gallagher, 24-42. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

MacKenzie, John M. 1996. “David Livingstone and the Worldly After-Life: Imperialism and Nationalism in Africa.” In David Livingstone and the Victorian Encounter with Africa, edited by John M. MacKenzie, 203-16. London: National Portrait Gallery.

Martelli, George. 1970. Livingstone’s River: A History of the Zambesi Expedition, 1858-1864. London: Chatto & Windus.

Mathews, Basil. 1912. Livingstone the Pathfinder. London: Oxford University Press.

Northcott, Cecil. 1957. Livingstone in Africa. London: Lutterworth.

NourbeSe Philip, Marlene. 1991. Looking for Livingstone: An Odyssey of Silence. Toronto: Mercury.

Paton, Alan. 1958. “The Last Journey.” PC1/3/6/1-2; PC1/3/6/4. Alan Paton Centre & Struggle Archives. University of KwaZulu-Natal.

Pettitt, Clare. 2007. Dr. Livingstone, I Presume?: Missionaries, Journalists, Explorers, and Empire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Pownall, David. 2000. “Livingstone and Sechele.” In Plays One, 71–130. London: Oberon Books.

Rapp, Dean, and Charles Weber. 1989. “British Film, Empire and Society in the Twenties: The ‘Livingstone’ Film, 1923-1925.” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 9 (1): 3–17.

Rupke, Nicolaas A. 2008. Alexander von Humboldt: A Metabiography. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Strachey, Lytton. 1918. Eminent Victorians. London: Chatto & Windus.

Waller, Horace. 1887. The Title-Deeds to Nyassa-Land. London: William Clowes and Sons.

Wetherell, M.A. 1925. Livingstone. Hero Films.

Young, Robert J.C. 2001. Postcolonialism: An Historical Introduction. Oxford: Blackwell.