Fever in the Tropics

Cite page (MLA): Lawrence, Christopher. "Fever in the Tropics." Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. University of Maryland Libraries, 2015. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/d90534e6-fa44-4235-af76-80c34119b996.

This essay contrasts nineteenth-century ideas (including Livingstone’s own) about fever with modern ideas about the causes and appropriate treatment for fever.

Introduction Top ⤴

Livingstone's writings recurrently return to the problem of fever as the greatest threat to the health of travellers in Africa. Livingstone died shortly before modern germ theory was developed and well before tropical medicine was established as a medical discipline. His accounts of the causes and cure of fever differ considerably from those given today. In addition, in Livingstone's time, there was great difference of opinion within the medical and scientific community as to the nature of fever.

Then and Now: Understanding Fever Top ⤴

Today there is, broadly speaking, consensus. Fever is usually regarded as a symptom of infection, and different infections produce different diseases. According to modern views, the infectious diseases that Livingstone might have encountered were of two sorts: first, diseases unique to tropical and subtropical climates, and second, diseases he could have seen in Europe.

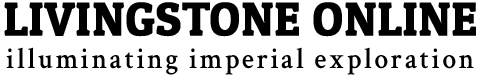

| (Left) A sick man projects his tongue while a doctor takes his pulse. Copyright Wellcome Library, London. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (Right) Medicine cabinet. Copyright Wellcome Library, London. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International |

A number of diseases peculiar to the equatorial latitudes, which were probably endemic in Livingstone's day, are caused by parasites. These parasites are transmitted by insects such as mosquitoes, flies, fleas, ticks and lice. The diseases include:

- malaria

- trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness)

- filariasis

- schistosomiasis

- blackwater fever

- dengue fever

- leishmaniasis.

Specificity fundamentally distinguishes the views of Livingstone and his contemporaries from those held today. Doctors now regard febrile diseases as specific entities because they have specific causes: malarial parasites, worms, bacteria, and so on.

Livingstone, however, perceived fever (with exceptions) as a single, essential disease whose form varied according to a host of factors both individual and general. In this view, the form changed according to age, sex, heredity, constitution, climate, and diet, as well as what we might now see as unscientific causes such as moral influences and occupation.

Livingstone's rousers. Copyright Wellcome Library, London. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International |

From Livingstone’s perspective there were no such things as tropical diseases, merely varieties of fever encountered in Africa provoked by local conditions. The same set of causes in a healthy, robust individual might produce a common cold and in a sickly person lead to fatal fever. In the 12 May 1859 entry in his Zambezi Journal, Livingstone noted: "The attacks [of fever] however were so modified by our being well provided for [... they] have resembled greatly common colds."

Fevers from Africa to London Top ⤴

In appropriate circumstances similar fevers could and (according to contemporary observers) did appear in, say, London. Writing to Thomas Maclear on 21 June 1862, Livingstone observed: "trying to get rid of the fever in the delta is like trying to cure the fever in the low overcrowded lodging houses of London or in houses with open cesspools beneath." In other words, Livingstone perceived fever to be a single disease with local manifestations.

Two letters Livingstone wrote to the Medical Times and Gazette (Livingstone and Kirk 1860; Livingstone 1863) beautifully illustrate this view. In these letters, Livingstone and Kirk identify "the fever" (italics added), not fevers, as the great obstacle to the advance of European nations into Africa. They note that when Charles Livingstone had fever, the symptoms were "such as we see in Europe." Like public health reformers in Britain, Livingstone and Kirk also identify an "offensive smell" as a sign that fever is likely to be encountered.

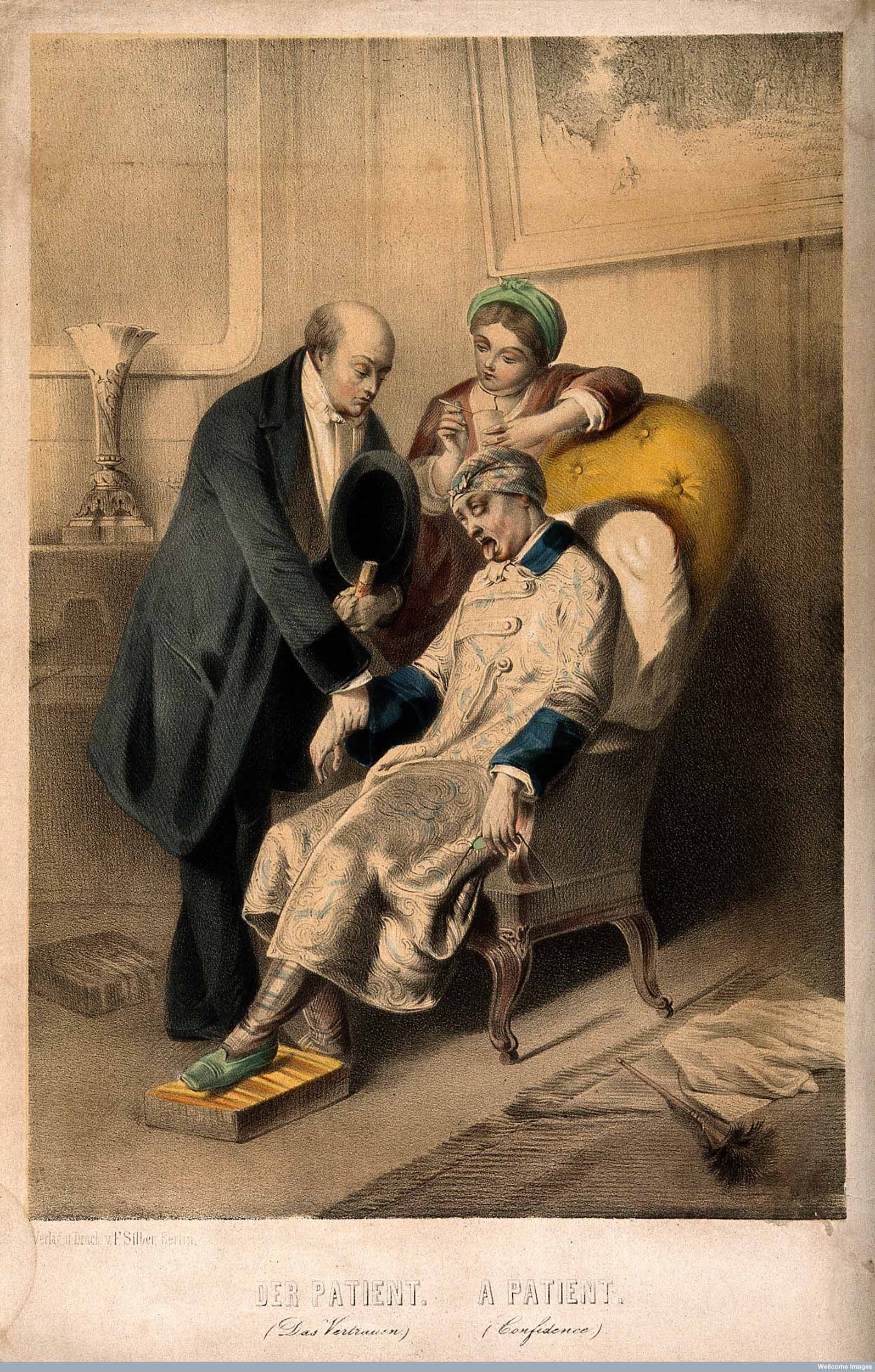

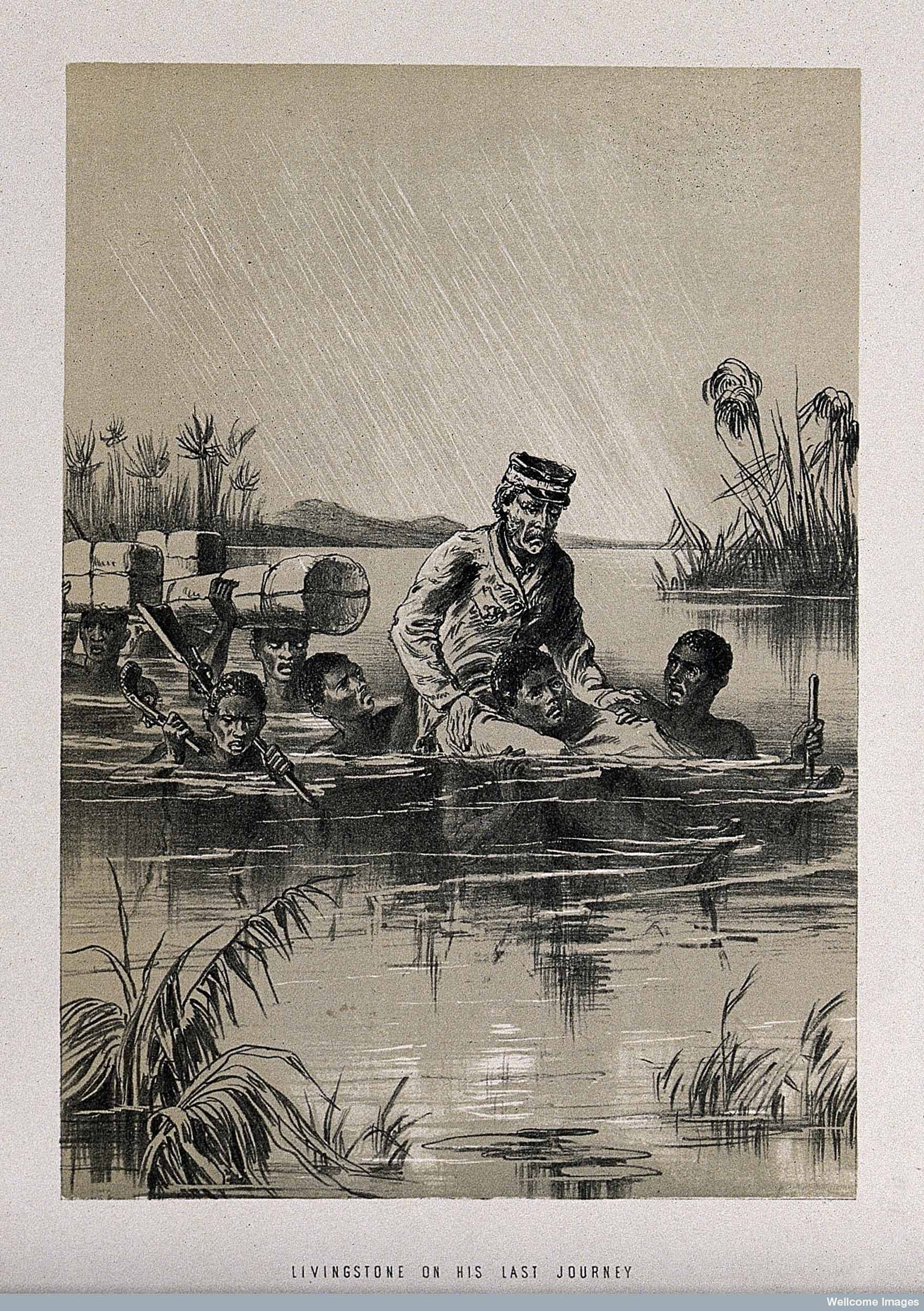

| (Left) "Livingstone on His Last Journey." Copyright Wellcome Library, London. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (Right) "The Last Mile." Copyright Wellcome Library, London. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International |

Livingstone and Kirk go on to detail their belief that swamps generate fever. This is as true of London as Africa or India. "You have actually a larger area of cesspool and marsh around and above London than exists in the Elephant Swamp," Livingstone writes. Individually, fever arises in those who are "worn out by constitutional disease" and are "inactive," rather than individuals who engage in morally uplifting "active exercise" and "hard work." Additionally, Livingstone and Kirk suggest that a "good diet" is more valuable than quinine and that taking fever "in its milder form first" to adapt one’s constitution will also aid prevention (Livingstone 1863).

This account of fever had great virtues in the nineteenth century, although it is completely alien to modern views. First, the account permitted very close-grained observation of febrile attacks and their relations to the environment. Livingstone was an excellent natural historian and his descriptions of the areas where fever prevailed include accounts of the dangers of low-lying marshy ground and the association between fevers and the presence of mosquitoes and tsetse fly (he did not say these creatures transmitted or caused fever). Today specialists regard these insects as the vectors of malaria and trypanosomiasis.

Treating Fever Top ⤴

Livingstone's model of fever stressed the virtues of sanitation. When two hundred liberated slaves were congregated together, their "dropping" produced a "pest hole." What Livingstone's approach to fever could not do was generate powerful drugs which could be used to target disease-producing parasites. This development was a consequence of the causal model built into modern germ theory and the experimental approaches of the laboratory sciences.

Nonetheless Livingstone was well aware of the value of quinine for fever that assumed an intermittent or "malarious" character, although he would not have recognised a distinct disease, malaria. In 1850, he adopted the practice of giving quinine with a purgative and found it successful in the case of two of his children.

"Quinine," Livingstone writes, "was found invaluable in the cure of the complaint [malaria], as soon as pains in the back, sore bones, headache, yawning, quick and sometimes intermittent pulse, noticeable pulsations of the jugulars, with suffused eyes, hot skin, and foul tongue, began” (Livingstone and Livingstone 1865:83).

Cinchona plant from which quinine is extracted (from Robert Bentley's Medicinal Plants), 1880. Copyright Wellcome Library, London. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International |

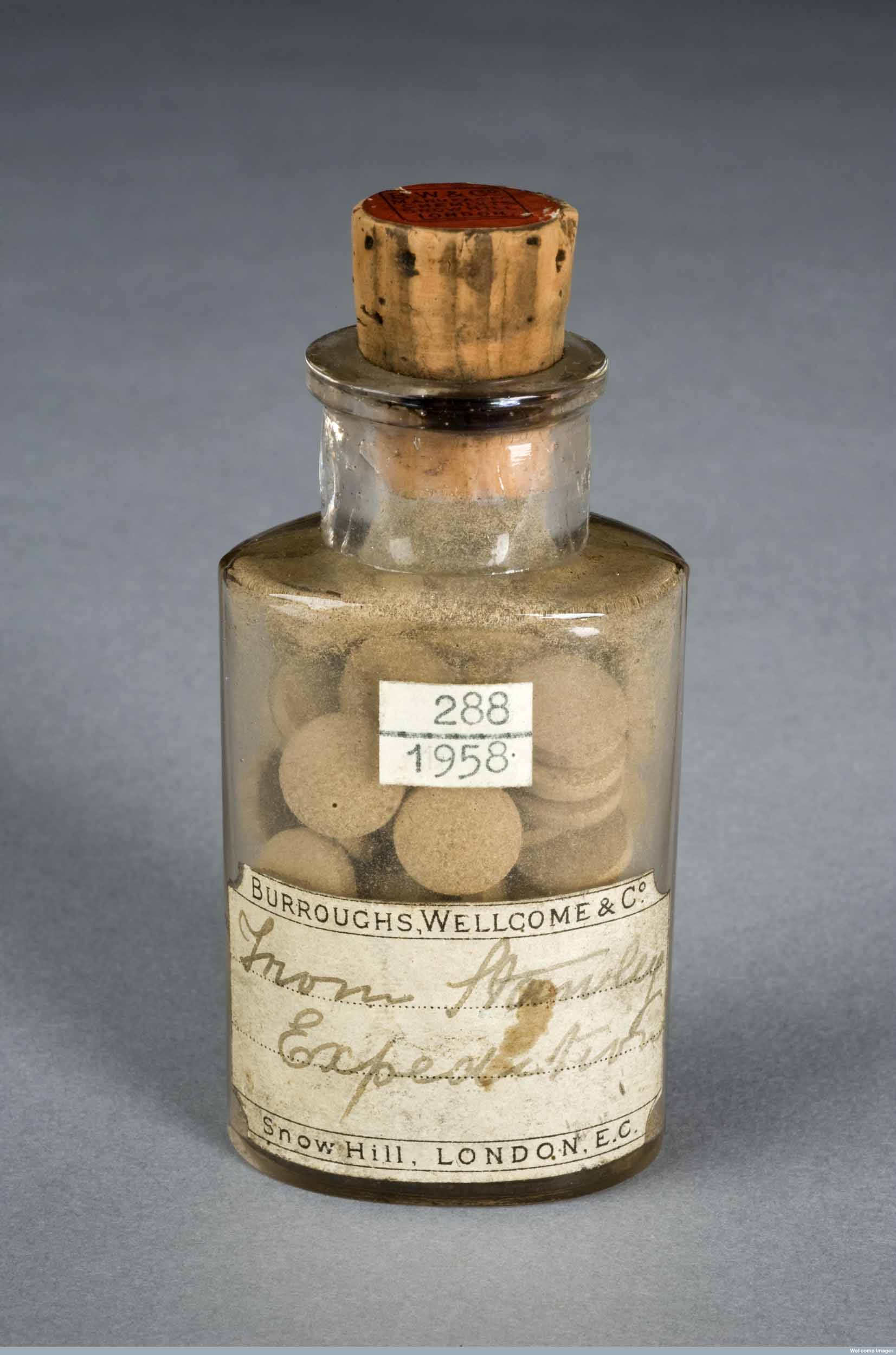

His remedy was "composed of from six to eight grains of resin of jalap, the same of rhubarb, and three each of calomel and quinine, made up into four pills, with tincture of cardamoms, usually relieved all the symptoms in five or six hours. Four pills are a full dose for a man – one will suffice for a woman. They received from our men the name of 'rousers,' from their efficacy in rousing up even those most prostrated” (Livingstone and Livingstone 1865:83).

Further Reading Top ⤴

Gelfand, Michael. 1957. Livingstone the Doctor; His Life and Travels: A Study in Medical History. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Hamlin, Christopher. 1998. Public Health and Social Justice in the Age of Chadwick: Britain, 1800-1854. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Harrison, Mark. 1999. Climates & Constitutions: Health, Race, Environment and British Imperialism in India, 1600-1850. New Delhi; Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kipple, Kenneth F., ed. 1993. The Cambridge World History of Human Disease. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Livingstone, David, and John Kirk. 1860. “Remarks on the African Fever on the Lower Zambezi, 12 November 1859.” In Dr. Livingstone’s Cambridge Lectures (etc.), edited by William Monk, 2nd Edition, 370–75. Cambridge: Deighton, Bell, and Co.

Livingstone, David. 1863. “Letter to Editor of the Medical Times and Gazette, 26, 27 January [1863].” Medical Times and Gazette (London), 2: 127-28.

Livingstone, David, and Charles Livingstone. 1865. Narrative of an Expedition to the Zambesi and Its Tributaries. London: John Murray.

Wallis, J.P.R. 1956. The Zambezi Expedition of David Livingstone, 1858-1863. London: Chatto & Windus.