Southern Africans and the Advent of Colonialism

Cite page (MLA): McDonald, Jared. "Southern Africans and the Advent of Colonialism." Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, eds. Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. University of Maryland Libraries, 2015. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/77590f20-a6f3-4721-85ff-22b52973f313.

This essay provides a summary of the most important historical events and processes relating to the peoples of southern Africa. The essay also explains the social and political context of the sub-continent from the Stone Age through to the mid-nineteenth century, when Livingstone first arrived in the region. The essay concludes with a glossary that defines key terms used in the text.

- Introduction

- The Earliest Inhabitants

- Human Settlement and the Climate

- The Arrival of Europeans

- The Expanding Cape Colony

- The Advance of the Colonial Frontier

- The Transition from VOC to British Rule

- A New Mission Field Opens Up

- The Era of Reform

- Boer Discontent and the Great Trek

- Social and Political Change in the Interior

- Traders and Raiders along the Trans-Gariep Frontier

- The Mfecane and the Rise of the Zulu Kingdom

- The Mfecane Draws to a Close

- The Consolidation of European Political Power

- Livingstone in Context

- Acknowledgements

- Glossary

- Further Reading

Introduction Top ⤴

By the mid-nineteenth century, southern Africa was a region characterised by intense conflict. The scale of this conflict had increased over the course of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, resulting in significant demographic shifts among the region’s population groups. In order to understand why, it is necessary to trace the history of human settlement in the African sub-continent from the pre-colonial period.

The Earliest Inhabitants Top ⤴

The earliest inhabitants of southern Africa were the San, or Bushmen, who were descendants of Late Stone Age peoples. Over the course of several thousand years, the San came to pursue their nomadic lifestyle across the region, from the south-west to the north-east.

With their primary mode of subsistence being hunting and gathering, and with their social organisation taking the form of small, kin-related groups, the San were highly mobile and adaptable to the changing environments of the sub-continent.

An example of San rock art found in the Ukhahlamba/Drakensberg World Heritage Site. Copyright Jared McDonald. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported

Following the San, were the Khoekhoe, who settled in southern Africa approximately 2500 years ago. The Khoekhoe supplemented their hunting and gathering with pastoralism. Unlike the San, the Khoekhoe tended to be more settled and the ownership of cattle and other livestock served as an important marker of status and authority.

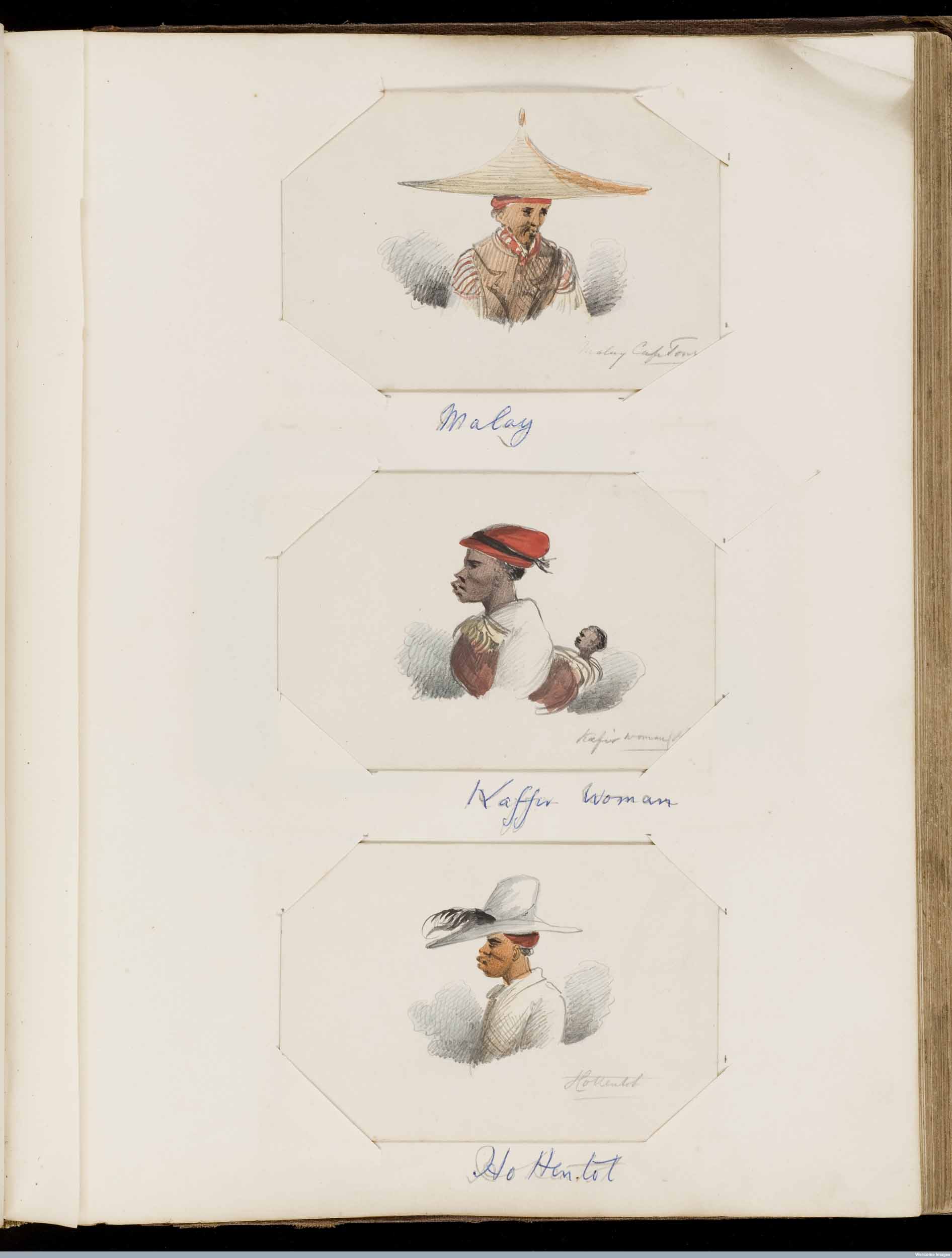

Khoekhoe groups sustained larger numbers than the San and tended to follow hereditary "chiefs." By the sixteenth century, Khoekhoe polities, such as the Hessequa, Nama and Attaqua, came to occupy most of the region south of the Gariep River (Orange River) and west of the Fish River.

Human Settlement and the Climate Top ⤴

From 1100 CE onwards, during the Middle Iron Age, Bantu-speakers moved south from central Africa’s Great Lakes region in a series of migrations. There is also evidence of waves of migration from the west coast, around present-day northern Angola.

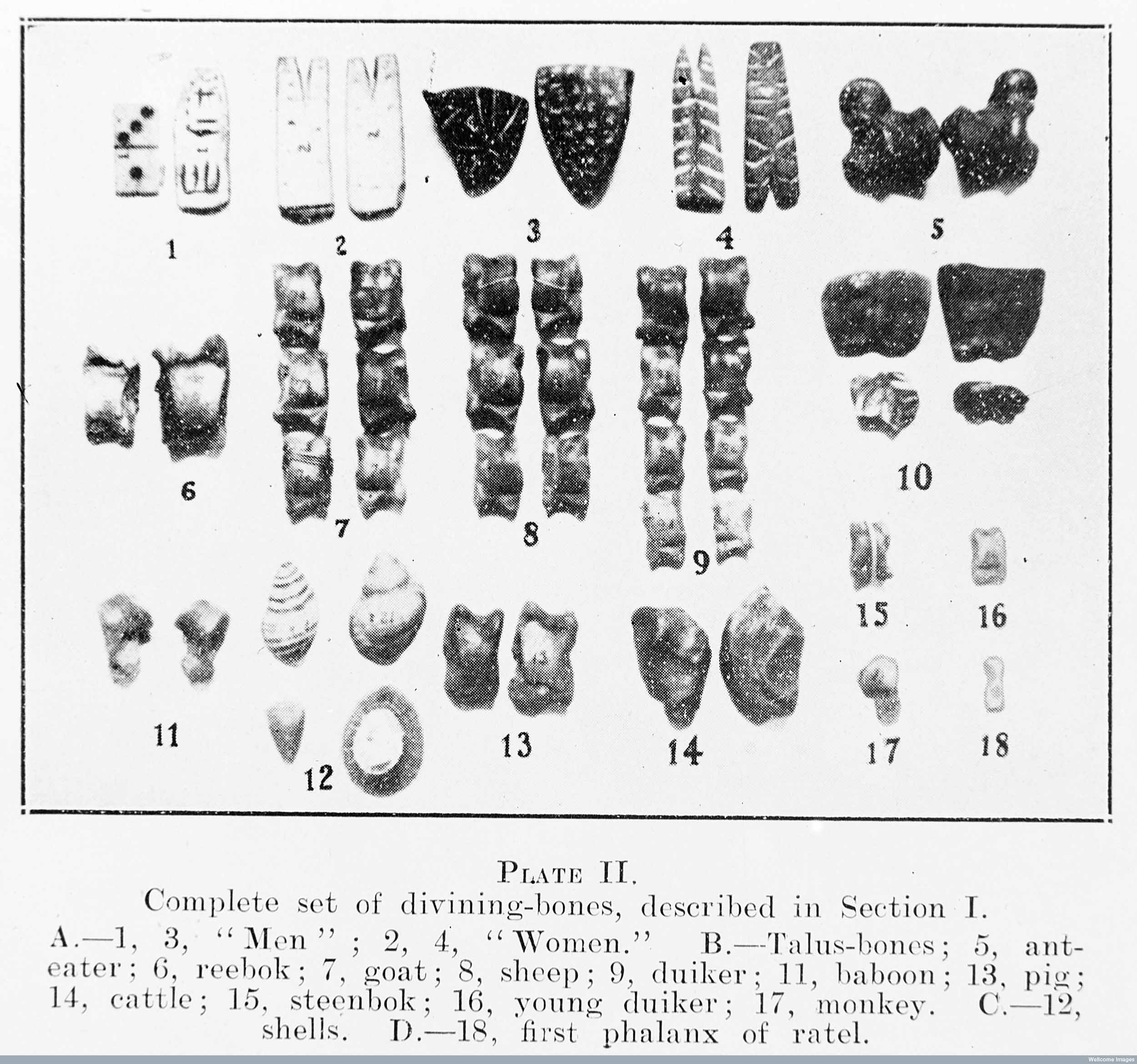

The Bantu-speakers practiced mixed-subsistence farming and tended to form socially complex communities. Some of these communities became kingdoms, eventually developing into small African states. Examples of such kingdoms include Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe.

By 1600 CE two Bantu-speaking branches had established themselves in present-day South Africa. The Nguni came to settle along the eastern coastal belt while the Sotho-Tswana settled across the eastern highland.

Illustration of a complete set of divining bones from Bantu Studies, by K.M. Watt and N.J.V. Warmelo. Copyright Wellcome Library, London. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

Both groups sought out reliable rainfall and soils suited to crop agriculture in order to sustain their agro-pastoral way of life. In addition to agriculture, their subsistence and economic activities included herding, hunting and trading.

Human settlement in southern Africa thus reflects the region’s climatic conditions. The eastern half of southern Africa has a high summer rainfall pattern, while the western half is much drier and often experiences drought.

In contrast to the rest of the region, the south-western Cape has a Mediterranean climate, characterised by wet winters and dry summers. The south-western Cape is also free of malaria and tsetse fly.

The Arrival of Europeans Top ⤴

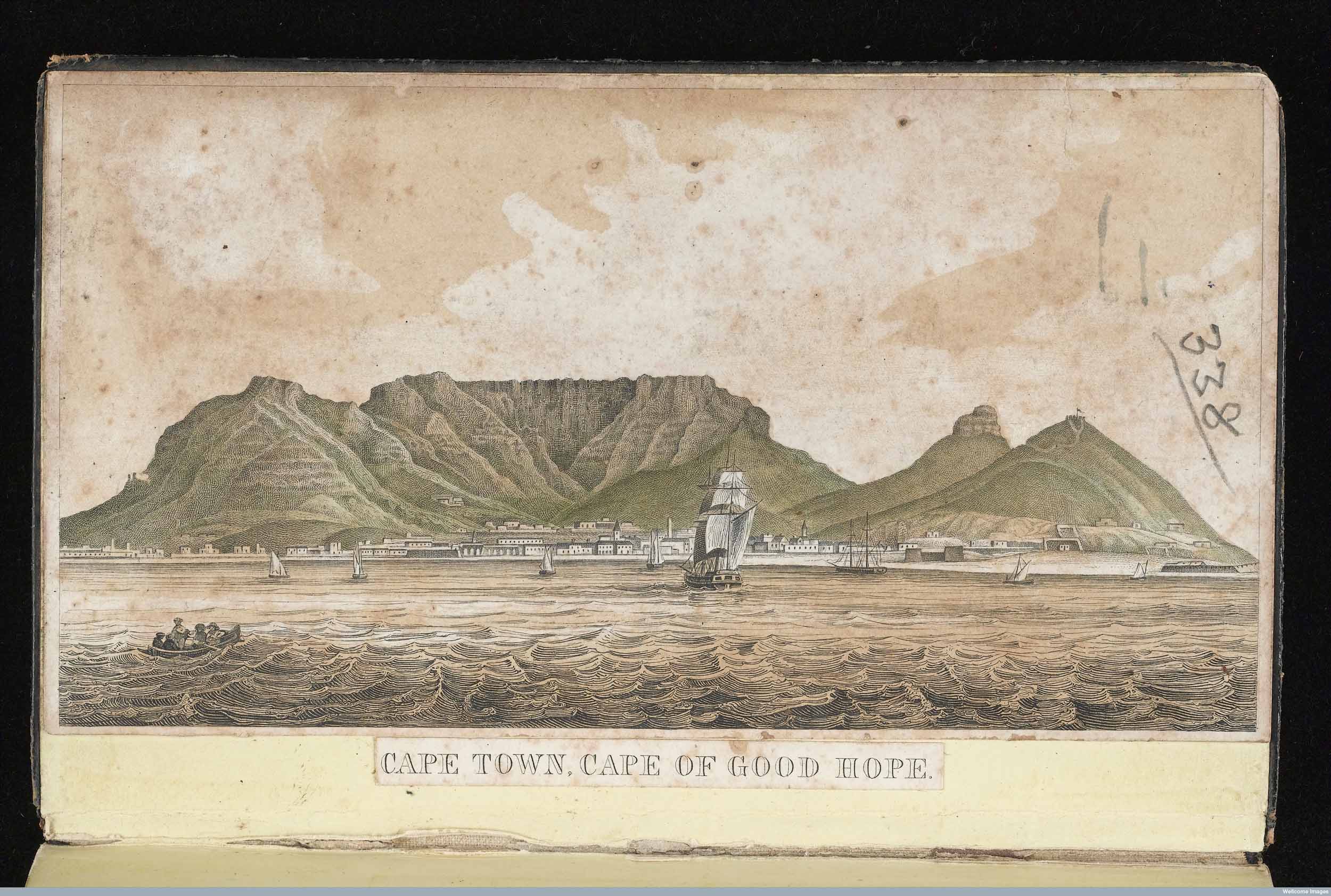

The quality of the south-western Cape’s climate was not lost on those European sea-faring nations who sailed around the southern tip of Africa in a bid to plot a sea route to the East. The Portuguese were the first to accomplish the feat and by the mid-sixteenth century the Cape of Good Hope’s strategic position on the trade route to Asia began to draw more Europeans to the region.

It was the mercantilist Dutch East India Company, or Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC), that first settled at Table Bay. In 1652 a fort was built and a small trading port established at the site. These were the rudimentary beginnings of the modern city of Cape Town.

![Ink sketch of 'Table Bay from the Mountain' [Table Mountain], Showing Lion's Head and Lion's Rump and Cape Town, 1840, by Robert McCormick. Copyright Wellcome Library, London. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).](/sites/default/files/life-and-times/southern-africans-and-the-advent-colonialism/L0046599-article.jpg)

Ink sketch of "Table Bay from the Mountain" [Table Mountain], Showing Lion's Head and Lion's Rump and Cape Town, 1840, by Robert McCormick. Copyright Wellcome Library, London. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

At first the VOC did not intend to colonize the region, but rather focused on supplying passing ships with fresh produce and meat. Being a convenient half-way stop on the Europe-to-Asia sea route, the demand for life-saving, scurvy-preventing supplies was high. In 1657, Dutch immigrants, known as burghers, were allowed to settle and farm on the outskirts of the port settlement, providing the VOC with fruit, vegetables, wine and beer for sale to ships’ crews.

The Expanding Cape Colony Top ⤴

The trading port grew rapidly and so did the demand for labour, which was in short supply. In order to address this, slaves were first imported to Cape Town in 1658. The slave population was eclectic in origin. They came from numerous places along the Indian Ocean rim, including Java, the Malay Peninsula, Ceylon, Madagascar, and the east African coast.

Initially, the VOC bartered and traded with the Khoekhoe for their large herds of cattle and sheep. However, the VOC’s demand for livestock grew to such an extent that it began to place strain on several Khoekhoe polities. As more and more European migrant stock farmers, also known as trekboers, advanced into the interior, so conflict with Khoekhoe and San (Khoesan) over the land and its resources ensued.

Slave chain for children. Copyright Livingstone Online (Gary Li, photographer). May not be reproduced without the express written consent of the National Trust for Scotland, on behalf of the Scottish National Memorial to David Livingstone Trust (David Livingstone Centre).

The Advance of the Colonial Frontier Top ⤴

European encroachment to the north and east of Cape Town was steady over the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, in spite of concerted Khoesan resistance. The loss of land and livestock, coupled with the introduction of European diseases, in particular smallpox, resulted in the rapid disintegration of Khoekhoe social and political organisation.

The San were treated with particular disdain by the trekboers, who regarded their hunter-gatherer lifestyle as backward and uncivilized. Conflict along the north-eastern frontier culminated in a genocidal campaign of extermination against the San during the 1770s and 1780s.

| Lantern Slides of the Life, Adventures, and Work of David Livingstone. Courtesy of the Smithsonian Libraries, Washington, D.C. |

For the trekboers, the most fertile land lay to the east of Cape Town. With its high rainfall and numerous rivers, the Eastern Cape had also appealed to the Xhosa, the southernmost, Bantu-speaking agro-pastoralists. Conflict between the two quickly followed. From 1779 to 1879, nine frontier wars were fought between the Xhosa and the Cape Colony.

The Transition from VOC to British Rule Top ⤴

In 1795, the VOC was facing bankruptcy. In a bid to prevent post-revolutionary France from acquiring a foothold at the strategic Cape, Great Britain captured the territory in the same year. Britain was better equipped and more determined to impose its own vision on the Cape than the VOC had been.

The importation of slaves to Cape Town was abolished in 1807 and settler immigration from Britain also increased, especially after 1820. For much of the early nineteenth century, the British colonial authorities at the Cape were influenced by humanitarian ideas stemming from the evangelical revival at home and the anti-slavery campaign.

Slave reforms were introduced during the 1820s and early 1830s, curbing the authority masters held over their slaves, as Britain moved towards the eventual abolition of slavery in its colonial territories. These reforms were hugely unpopular with the Boer slave-owners of the Cape. In 1834 a four year period of apprenticeship was ushered in before the slaves were finally emancipated on 1 December 1838.

A New Mission Field Opens Up Top ⤴

With the British occupation, the Cape Colony also emerged as an inviting mission field. In 1799, the London Missionary Society (LMS) despatched its first group of missionaries to the region.

The two earliest missions were founded among the Xhosa in the east and among the San to the north. Both missions were short-lived, but this did not deter other missionaries and mission societies from following. Subsequently, the Rhenish, Glasgow, Wesleyan and Paris societies entered the southern African mission field.

Between 1799 and the 1840s, several hundred missionaries arrived and eighty mission stations were established in the Cape Colony as well as beyond its official boundaries. The favourable climate, together with the success the missionaries experienced among the remnants of the Khoekhoe, resulted in the Cape having the highest concentration of missionaries in the world by the mid-nineteenth century.

Though preceded by the Moravians, the LMS would become the most prolific mission society at the Cape. They would also become the most politically instigative, campaigning for indigenous rights on behalf of the Khoesan and Xhosa via their evangelical-humanitarian networks.

The mission effort to promote the protection of African rights was set in motion by the earliest representatives of the LMS at the Cape, such as Johannes van der Kemp and James Read. Livingstone would take up this mantle and become one of the most famous champions of the cause later in the century.

The Era of Reform Top ⤴

For as long as Britain’s colonial authorities in London and Cape Town endorsed humanitarian principles, the missionaries were influential in shaping relations between the Cape’s indigenous, slave and settler inhabitants. During the 1820s and 1830s, the evangelical-humanitarian lobby’s influence on colonial affairs was at its height.

Major liberal reforms were introduced at the Cape that were intended to improve Khoesan labour conditions and restrict the power of the European settlers over both their servants and slaves. The abolition of slavery in 1834 was followed by the House of Commons Select Committee on Aborigines in 1836 and the founding of the Aborigines’ Protection Society the following year.

The Select Committee on Aborigines heard evidence on the devastating effects of settler colonialism upon indigenous peoples in British territories, including New South Wales, Van Dieman’s Land (Tasmania), New Zealand and the Cape Colony. The Boers were criticised for their treatment of the Khoesan and for instigating wars with the Xhosa along the eastern frontier, raising their indignation against Britain’s rule at the Cape.

"Cape Town, Cape of Good Hope," from the Diary of Thomas Graham, c. 1849-50. Copyright Wellcome Library, London. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

Boer Discontent and the Great Trek Top ⤴

The combination of labour reforms and the abolition of slavery resulted in large numbers of Boers, known as Voortrekkers, voluntarily opting to leave the Cape Colony. Several thousand trekked further northwards into the southern African interior in order to escape British interference and to establish their own states.

The ensuing migrations are commonly referred to as the Great Trek. By the early 1850s, the Voortrekkers were able to secure British recognition of their new Boer republics, the Orange Free State and the Transvaal, also known as the Zuid Afrika Republiek.

Social and Political Change in the Interior Top ⤴

Meanwhile, the southern African interior escarpment, or Highveld, had witnessed a significant political revolution among the area’s Bantu-speaking peoples. At first gradual, by the early nineteenth century this revolution sparked rapid demographic shifts and even the de-populating of some parts of the region.

The late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries was a period of widespread internecine conflict among the Sotho-Tswana and Nguni peoples of southern Africa. These waves of conflict, forced migration and socio-political consolidation are referred to as the Mfecane, meaning "the crushing," or "the scattering."

The ripple effect of the Mfecane covered a vast geographical area. Conflicts between competing groups stretched from the Eastern Cape frontier all the way to present-day Tanzania, Malawi, Zimbabwe and Mozambique. The reasons for the Mfecane are contested among historians, but several influences have been identified.

The introduction of maize around this time meant that some groups were able to sustain larger numbers. However, maize requires large amounts of water. Evidence of a severe drought in the southern African interior at the turn of the nineteenth century suggests that widespread hunger was a contributing factor to the Mfecane.

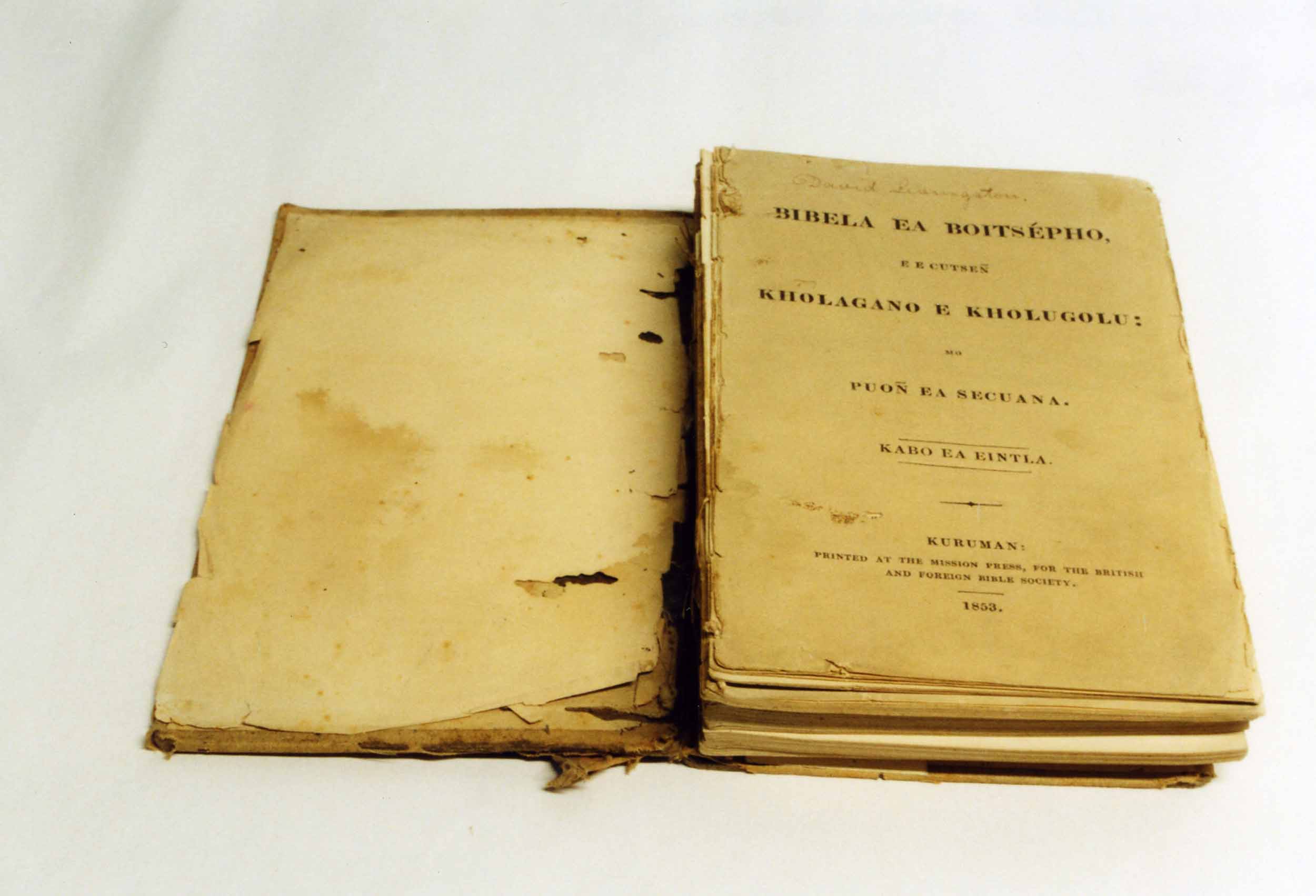

Christian missionaries were sought out for the protection and provision they could offer during these events. Displaced people tended to gather around mission stations. This did not, however, guarantee greater receptivity to the gospel, much to the frustration of many missionaries.

Sechuana Bible, 1853. Copyright Livingstone Online (Gary Li, photographer). May not be reproduced without the express written consent of the National Trust for Scotland, on behalf of the Scottish National Memorial to David Livingstone Trust (The David Livingstone Centre).

Traders and Raiders along the Trans-Gariep Frontier Top ⤴

Another factor in the unfolding of the Mfecane was the demand for slaves and ivory emanating from Arab, Swahili and Portuguese traders on the East African coast, especially modern-day Mozambique. This resulted in the exchange of horses and firearms with inland communities and the emergence of powerful groups of slave and livestock raiders, such as the Korana.

The Korana were one of several Oorlam communities to emerge along the Trans-Gariep frontier during this period. Oorlam was a term used to refer to mixed race groups of Khoesan, slave, European and Sotho-Tswana commixture. The Korana were predominantly of Khoekhoe and Sotho-Tswana extraction.

The early nineteenth century also witnessed the emergence of the Griqua as a dominant group along the northern frontier of the Cape Colony. The Griqua were made up of several pastoral communities with mixed Khoesan, slave and European ancestries.

With the aid of the LMS, the Griqua were organised into captaincies in the 1820s. They spoke Dutch and wore western-style clothing. Their geographic location, to the north of the Cape Colony and to the west of Delagoa Bay, meant they were well poised to take advantage of the expanding trade in guns, horses and slaves.

The Mfecane and the Rise of the Zulu Kingdom Top ⤴

Increasing conflict over trade and resources led to the consolidation of smaller polities into larger "tribal" groups. In this context, leaders who were able to provide security and dispense patronage attracted more followers.

It was due to processes related to the Mfecane that some of southern Africa’s most prominent ethnicities and royal houses emerged, many of which still exist today. The Zulu kingdom under Shaka was one of the most significant.

A group of Zulu women carry beer to a wedding celebration. Copyright Wellcome Library, London. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

Under Shaka’s leadership, several small Nguni groups along the eastern coastal belt were forcibly merged to form the Zulu, who today constitute South Africa’s most numerous population group. Shaka was an astute military tactician. He transformed the Zulu army, or impi, into a formidable force in the region.

Shaka’s military campaigns against neighbouring groups in what is today KwaZulu-Natal had a ripple effect across the interior. Groups were either absorbed into the Zulu or forced out of their territories.

Elephant in the Morning Haze in Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Copyright Angela Aliff. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported

Shaka was not responsible for the Mfecane, rather he was reacting to the Mfecane, which had begun several decades before his rise to power. Nonetheless, his influence was considerable and his reign as king of the Zulu ushered in a fresh, violent wave to the overall process.

The Mfecane Draws to a Close Top ⤴

By the late 1830s, the Mfecane was drawing to a close. Other prominent "tribal" groups that also emerged as a consequence included the Ndebele under Mzilikazi and the Sotho under Moshoeshoe, who went on to found the modern Kingdom of Lesotho.

The Voortrekkers added to the competition over land and resources after their arrival on the Highveld and the eastern coastal belt in the late 1830s. Major battles between the Voortrekkers and the Zulu and Ndebele occurred.

David Livingstone - St Pauls (Painted Magic Lantern Slide), c.1857. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland |

The newly consolidated African polities also fought with each other, often raiding livestock and capturing slaves for sale at Delagoa Bay and to the Voortrekkers. Alliances of convenience were struck up between groups as well. A notable case in point was the Griqua-Voortrekker alliance which clashed with the Ndebele.

Some astute African leaders realised that missionaries could be useful political allies. Missionaries could act as intermediaries with colonial authorities, provide counsel and facilitate trade, even of guns and horses. For example, Moshoeshoe consulted missionaries sent by the Paris Evangelical Missionary Society on the threat posed by Voortrekker encroachment on Sotho lands.

The Consolidation of European Political Power Top ⤴

Major demographic shifts continued to characterise southern Africa for the remainder of the nineteenth century. The pace of change quickened following the discovery of diamonds in the 1860s and the world’s richest gold deposits in the Transvaal in the 1880s, ushering in the industrialisation of the region.

In 1850 there were approximately twenty independent societies occupying what is today South Africa. By the close of the century, this entire region was made up of the two Boer republics and the two British colonies, the Cape Colony and Natal. All the formerly independent Khoesan and Bantu-speaking societies fell under their control.

Livingstone in Context Top ⤴

Following Livingstone’s arrival at the Cape in 1841, he travelled north to a region that was largely unexplored in a bid to find new locations for the establishment of missions. He was first based at Kuruman among the Tswana. Kuruman was one of the LMS’ flagship missions in southern Africa and it was administered by Robert Moffat, whose daughter, Mary, married Livingstone in 1845.

Livingstone interacted with other prominent LMS representatives at the Cape, such as the Society’s superintendent, John Philip. He was thrust into the heated debate between the LMS and settlers over the future of the Colony and its indigenous inhabitants.

3 x water colour sketches: 'Malay', 'Kaffir Woman', 'Hottentot', c.1867. From the RAMC Muniment Collection. Copyright Wellcome Library, London. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International |

More overtly racist sentiments began to take hold in Britain and her settler colonies from the 1840s onwards. Even though evangelical-humanitarians were being increasingly sidelined in imperial affairs, Livingstone carried on the LMS tradition of campaigning on behalf of Africans.

Like Philip and others associated with the Aborigines’ Protection Society, Livingstone did not oppose British imperialism, but rather unchecked settler colonialism. He thought of British imperialism as a "civilizing" and "Christianizing" influence, whereas he regarded the settlers, in particular the Boers, with disdain.

Livingstone arrived in southern Africa at a time when the region was reeling from major demographic upheaval, violent frontier conflicts and extensive slave-raiding. His early encounters and experiences were to influence his political views, as well as his choices of where to venture and to proselytise.

Acknowledgements Top ⤴

This is an expanded version of a piece originally published in Susannah Rayner, ed., The Life and Afterlife of David Livingstone (London: SOAS University of London, 2014), 45–55. It is extended here with the kind permission of SOAS, University of London.

Glossary Top ⤴

Boer - European farmer at the Cape; predominantly, though not exclusively, of Dutch origin

burgher - a free citizen not employed by the VOC

Griqua - pastoral, mixed race community with Khoesan, slave and European ancestries; settled along the Trans-Gariep frontier

Khoekhoe - meaning "men of men," this was the term the Cape’s indigenous, pastoral communities used to refer to themselves

Khoesan - term used to refer to Khoekhoe and San; both pastoralists and hunter-gatherers were incorporated into the Cape settler economy resulting in a blurring of the two categories

Koranna - Oorlam group with Khoesan and Sotho-Tswana admixture

Oorlam - mixed race communities with varying degrees of Khoesan, slave, European and Sotho-Tswana commixture who emerged along the Cape’s northern frontier during the late eighteenth century

San - term used to refer to the Cape’s indigenous hunter-gatherer communities

trekboer - European migrant stock-farmer

Voortrekker - Dutch settlers who voluntarily left the Cape Colony in a series of emigrations during the 1830s in order to escape British control

Further Reading Top ⤴

Elphick, Richard, and Rodney Davenport, eds. 1997. Christianity in South Africa: A Political, Social and Cultural History. Cape Town: David Philip.

Keegan, Timothy. 1996. Colonial South Africa and the Origins of the Racial Order. Cape Town: David Philip.

Legassick, Martin Chatfield. 2010. The Politics of a South African Frontier: The Griqua, the Sotho-Tswana, and the Missionaries, 1780-1840. Basel: Basler Afrika Bibliographien.

Penn, Nigel. 2005. The Forgotten Frontier: Colonist and Khoisan on the Cape’s Northern Frontier in the 18th Century. Cape Town: Double Storey Books.

Pretorius, Fransjohan. 2014. A History of South Africa from the Distant Past to the Present Day. Pretoria: Protea Book House.

Ross, Robert. 2008. A Concise History of South Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Swanepoel, Natalie, Amanda Esterhuysen, and Philip Bonner, eds. 2008. Five Hundred Years Rediscovered: Southern African Precedents and Prospects. Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

Wylie, Dan. 2011. Shaka: A Jacana Pocket Biography. Johannesburg: Jacana Media.

![Letter to Robert Moffat 1, [2 March 1856?]. Moffat was commissioned by the London Missionary Society in 1816 and sent to South Africa. SOAS Library, University of London. Copyright Council for World Mission and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson, as relevant. Used by permission for private study, educational or research purposes only. Please contact SOAS Archives & Special Collections on docenquiry@soas.ac.uk for permission to use this material for any other purpose. Letter to Robert Moffat 1, [2 March 1856?]. Moffat was commissioned by the London Missionary Society in 1816 and sent to South Africa. SOAS Library, University of London. Copyright Council for World Mission and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson, as relevant. Used by permission for private study, educational or research purposes only. Please contact SOAS Archives & Special Collections on docenquiry@soas.ac.uk for permission to use this material for any other purpose.](/sites/default/files/life-and-times/southern-africans-and-the-advent-colonialism/liv_000882_0003-article.jpg)