Livingstone's Final Manuscripts (1865-1873)

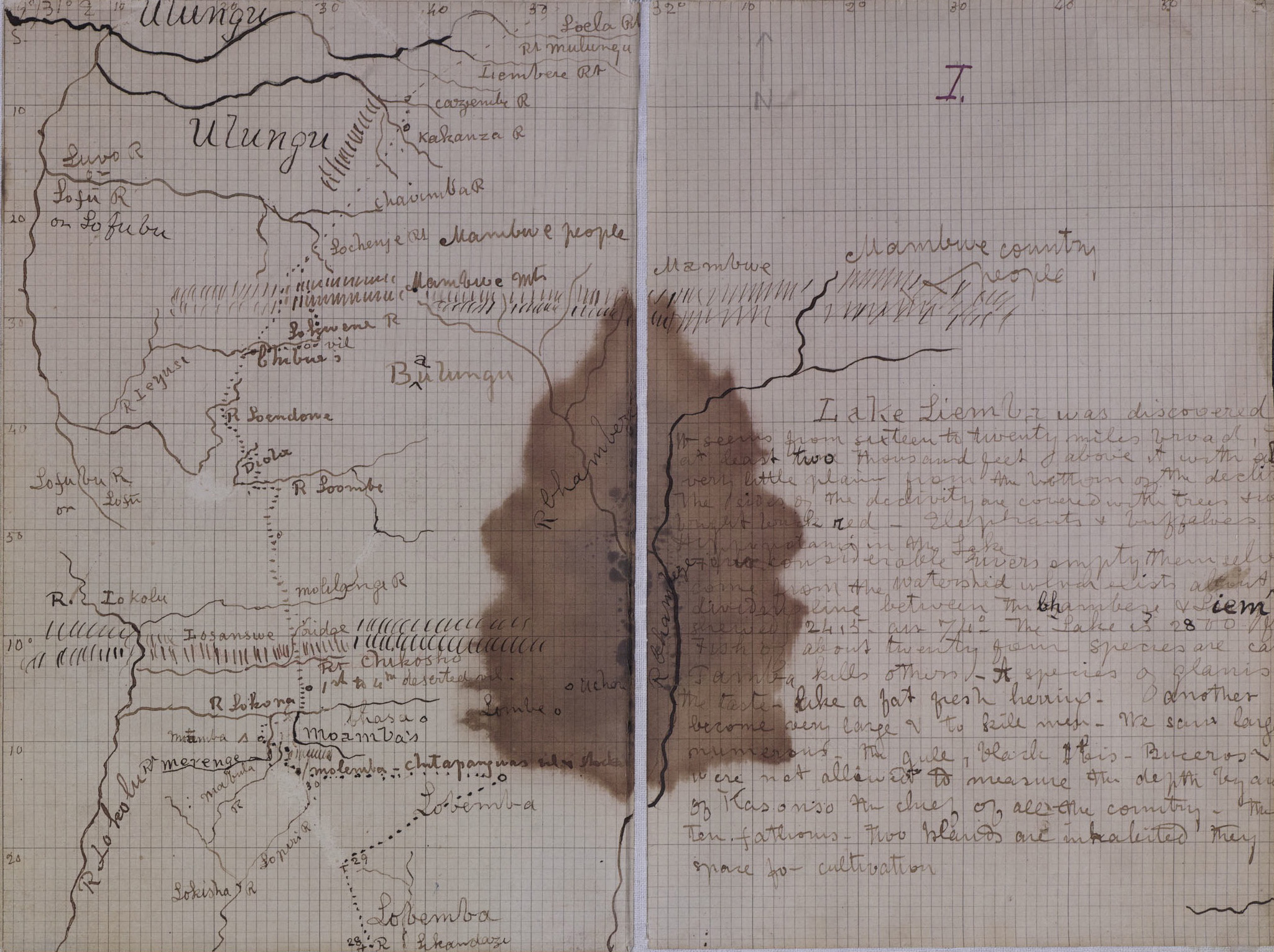

![Image of two pages from Livingstone's Field Diary XVI (Livingstone 1872h:[2]-[3]). CC BY-NC 3.0 Image of two pages from Livingstone's Field Diary XVI (Livingstone 1872h:[2]-[3]). CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/grid_images/liv_000016_0003-tile.jpg)

Cite edition (MLA): Ward, Megan, and Adrian S. Wisnicki, dirs. Livingstone's Final Manuscripts (1865-1873). First ed. In Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. University of Maryland Libraries, 2018. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/ef7677b7-0212-4c34-bb8e-ce826eefb0af.

Cite page (MLA): Ward, Megan, and Adrian S. Wisnicki. "Introduction to the Edition." In Livingstone's Final Manuscripts (1865-1873). Megan Ward and Adrian S. Wisnicki, dirs. Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. University of Maryland Libraries, 2018. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/ef7677b7-0212-4c34-bb8e-ce826eefb0af.

This page introduces our critical edition of Livingstone's final manuscripts (1865-1873) by summarizing the significance and scope of the present edition.

|

|

The MLA Committee on Scholarly Editions has awarded Livingstone’s Final Manuscripts (1865-1873) (first edition) the seal designating the edition as an MLA Approved Edition. Awarded: 19 September 2019 |

Introduction to the edition

The materials published through this critical edition of Livingstone’s final manuscripts (1865-1873) open a new phase in the study of nineteenth-century European exploration of Africa. Manuscripts resulting from David Livingstone’s final journey to Africa survive in abundance but have been difficult to access for almost a century and a half. This edition, for the first time, makes publicly available the full collection of final manuscripts held by the David Livingstone Centre in Blantyre, Scotland.

This is the largest single-archive collection of its kind. Our edition comprises over 2,700 images of original manuscript pages from Livingstone’s last expedition to Africa, with over 2,200 of those pages encoded, edited, and framed with modern critical essays. The manuscripts decisively dismantle the Victorian notion of the iconic explorer detached from history and instead take readers into a complex continent, teeming with diverse cultures, ideas, and networks of exchange.

| (Left; top in mobile) An image of a page of Field Diary X (Livingstone 1867c:[142]). (Right; bottom) An image of a page of Field Diary I (Livingstone 1865:[104]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. On the page in brown ink, Livingstone records local cultural and geographical information, much of it collected from African informants. The page in blue and black ink documents payments made to some of Livingstone's African porters. |

Unlike his first two journeys, Livingstone embarked on his third and final journey to Africa with no clear affiliations. Though he had the title “Roving Consul,” he was not paid by the British government for his work in examining the watershed of central Africa. And although he still considered himself a missionary at heart, he was not officially carrying out missionary work. Because of these ambiguities, the manuscripts in which Livingstone recorded his final travels (journals, diaries, notebooks, maps, and more) include a breadth of rhetorical strategies, as well as a wide array of information.

The manuscripts describe the cultures of diverse African ethnic groups, their technologies, and architectural practices; record zoological, botanical, and geological information; explore the vicissitudes of east African caravan culture and the Arab-led east and central African slave trades; and catalogue geographical, magnetic, and astronomical data. The manuscripts also include a wide range of illustrations and maps and, in addition, bear material witness to nineteenth-century Africa in the form of insects and plants pressed between manuscript pages as well as the many ways that diverse African environments have left stains and other marks on individual pages.

David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, 1867-1872, detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. Livingstone's maps, such as this one, can contain a complex array of textual data. The stain at the center of the image may also hold clues about the environments in which Livingstone created and/or transported the map.

The manuscripts are also notable for their geographical breadth and as records of cross-cultural social interaction. During the seven years of this final journey, Livingstone passed through vast regions of east and central Africa, which would today include Mozambique, Tanzania, Malawi, Zambia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. He was accompanied by porters he recruited en route plus those from farther afield: freed African slaves educated at a school in Nashik, India; men from the island of Anjouan, Comoros; and a contingent of Sepoys (Indian soldiers). In addition, he received aid from the very Arabs whose slave trade he despised. And while for years Livingstone traveled without contact with Europeans, this is also the journey in which Livingstone experienced his highly-publicized meeting with Henry M. Stanley in 1871.

Our critically mediated digital edition of these final manuscripts – only a small percentage of which had been edited to modern standards and published prior to this edition – will enhance critical analysis of nineteenth-century African and British imperial history as well as the production of nineteenth-century scientific knowledge. After Livingstone’s death in Africa in 1873, Horace Waller edited, radically revised, and published Livingstone’s manuscripts as the Last Journals (1874), a work that has been the primary source for this period of Livingstone’s life and his travels for the last 140 years.

Agnes and Thomas Livingstone, Daughter and Son of David Livingstone, Abdullah Susi, James Chuma, and Rev Horace Waller at Newstead Abbey, Nottingham, Discussing the Journals, Maps, and Plans Made by the Late David Livingstone, 1874. SOAS Library, University of London. Copyright Council for World Mission. Used by permission for private study, educational or research purposes only. The image is notable for the presence of nearly all the key individuals associated with the production of the Last Journals (1874) except Livingstone himself. The image is one of a series taken of Susi and Chuma with Livingstone's artifacts. For another such image, see our page on the Scope of the Edition.

Through the present edition, we publish in full a majority of the manuscripts upon which Waller based his edition. Moreover, our edition offers multiple versions of Livingstone’s texts – field diaries and rough notebooks, polished journals and maps, and a digital facsimile of Waller’s edition – in short, a collection of primary materials that allows users to study the creation, editing, and publication of Livingstone’s texts end to end. To orient readers and provide a critical framework, the edition also includes a rich array of paratextual materials.

Throughout this edition, our focus has been on foregrounding the many contexts of Livingstone’s travels: seeking out his information sources, his living conditions, his traveling partners, and his interlocutors. By publishing these difficult-to-access manuscripts, we hope to encourage vibrant scholarly debate. Our digital edition of the manuscripts from this period promises to transform our understanding of Livingstone’s last journey and will illuminate not only the many facets of nineteenth-century African life that Livingstone recorded, but also broader nineteenth-century Anglophone strategies for representing foreign peoples, cultures, and technologies.

![John Murray III and Anon., David Livingstone - Boat Scene (Painted Magic Lantern Slide), [1857], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND. John Murray III and Anon., David Livingstone - Boat Scene (Painted Magic Lantern Slide), [1857], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND.](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_014067_0001-carousel.jpg)

![Image of two pages from Livingstone's Field Diary XVI (Livingstone 1872h:[2]-[3]). CC BY-NC 3.0 Image of two pages from Livingstone's Field Diary XVI (Livingstone 1872h:[2]-[3]). CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000016_0003-carousel.jpg)

![David Livingstone, Map of Lakes Nyassa and Shirwa [1864?], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND; Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson, CC BY-NC 3.0 David Livingstone, Map of Lakes Nyassa and Shirwa [1864?], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND; Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson, CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000077_0001-tile.jpg)

![An image of a page of Field Diary X (Livingstone 1867c:[142]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of Field Diary X (Livingstone 1867c:[142]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/livingstones-final-manuscripts-1865-1873/liv_000010_0142-article.jpg)

![An image of a page of Field Diary I (Livingstone 1865:[104]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of Field Diary I (Livingstone 1865:[104]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/livingstones-final-manuscripts-1865-1873/liv_000001_0104-article.jpg)