The Final Field Diaries: General Overview

Cite page (MLA): Ward, Megan, and Adrian S. Wisnicki. "The Final Field Diaries: General Overview." In Livingstone's Final Manuscripts (1865-1873). Megan Ward and Adrian S. Wisnicki, dirs. Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. University of Maryland Libraries, 2018. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/c67fe71d-2072-4f67-8f1e-a69ac24e4ef9.

This essay focuses on three of the key themes that emerge across the twelve Livingstone field diaries (1865-73) included in this edition: ethnography, religion, and authority. The essay also analyzes how Livingstone understands the slave trade in relation to each of these categories. Throughout, the essay discusses how Livingstone’s representations of African and Arab cultures are framed by his own cultural values and beliefs.

- Introduction

- Scope of the Present Essay

- Ethnography

- Religion

- Authority

- Conclusion

Introduction Top⤴

Throughout his final journey, Livingstone took notes in a series of pocket-sized diaries, jotting down narrative accounts of daily life, scientific observations, lists, drawings, and various other kinds of observations. Rather than following predetermined topics, Livingstone used a scattershot approach in the diaries, documenting his experiences and ideas as they arose. As a result, the diaries offer a more immediate, less filtered look at Livingstone’s interests, particularly as he tended to revise and redevelop key ideas and events from the diaries when he copied them into the Unyanyembe Journal or recorded some of his ideas in letters to his correspondents.

![An image of a page of Field Diary XVI (Livingstone 1872h:[127]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of Field Diary XVI (Livingstone 1872h:[127]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/the-final-field-diaries-general-overview/liv_000016_0127-article.jpg)

An image of a page of Field Diary XVI (Livingstone 1872h:[127]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported.

Across the twelve diaries represented in this edition, though, three key theme emerge: ethnography, religion, and authority. Slavery and the slave trade also figure prominently in these diaries, but they arise consistently across these three main categories, demonstrating how slavery is a constant concern for Livingstone. Overall, close attention to the field diaries shows that they contain a rich vein of information about central African cultures, framed by British values in the form of Livingstone’s commentary and evaluations.

Scope of the Present Essay Top⤴

The twelve field diaries covered by this essay are as follows:

Field Diary I - 4 Aug. 1865-31 Mar. 1866. [Livingstone 1865]

Field Diary II - 4 Apr.-14 May 1866. [Livingstone 1866a]

Field Diary III - 14 May-30 June 1866. [Livingstone 1866b]

Field Diary IV - 1 July-5 Sept. 1866. [Livingstone 1866c]

Field Diary V - 5 Sept.-23 Oct. 1866. [Livingstone 1866d]

Field Diary VI - 24 Oct.-23 Dec. 1866. [Livingstone 1866e]

Field Diary VII - 26 Dec. 1866-1 Mar. 1867. [Livingstone 1866f]

Field Diary X - 9 Sept. 1867-2 Jan. 1868. [Livingstone 1867c]

Field Diary XIV - 14 Nov. 1871-14 Sept. 1872. [Livingstone 1871n]

Field Diary XV - 7 July-1 Dec. 1872. 1131. [Livingstone 1872g]

Field Diary XVI - 1 Dec. 1872-6 Apr. 1873. [Livingstone 1872h]

Field Diary XVII - 9 Apr.-28 Apr. 1873. [Livingstone 1873b]

These diaries are held by the David Livingstone Centre in Blantyre and constitute twelve of the seventeen numbered field diaries from Livingstone’s last expedition to Africa (1865-73). The remaining five diaries – Field Diaries VIII, IX, XI, XIII (held by the National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh) and Field Diary XII (held by the Livingstone Museum, Zambia) – are not included in this edition, but may be added to Livingstone Online at some future date.

Ethnography Top⤴

In his diaries, Livingstone made copious notes about the people and cultural practices he encountered, although he did not consider himself an ethnographer. He does, however, have consistent areas of interest when learning about other cultures, as well different strategies (lists, narratives, drawings) for representing those areas of interest and a philosophy of cross-cultural encounters. Livingstone’s observations are marked by a tension between his belief in approaching other cultures without prejudice and the implicit and unrecognized biases shaping his representations of African peoples.

▲ Areas of Interest. Though Livingstone does not necessarily follow any clear guidelines when reporting on ethnic groups, the field diaries do show consistent areas of interest when taken as a whole. For instance, Livingstone repeatedly creates lists of local place names, new vocabulary words, and crops and agricultural practices. In addition, he usually notes clothing, ornamentation of teeth, and the presence or absence of tattoos and other forms of personal decoration, as when he says of the Makonde, “many of the men profusely tattooed - teeth sharpened to points they say for beauty” (1866a:[38]). At various times, he also records information about language, body type, skin color, facial features, hair, diet, and residential architecture. This is often the only cultural information Livingstone documents, and he jots down such observations even when contact is limited to only a few representatives of a given ethnic group.

Other pieces of information are reported second-hand from unnamed sources, as in another of Livingstone’s observations of the Makonde: “they are said to fear the English – They sell each other to the Arabs” (1866a:[56]). This quotation also points to Livingstone’s interest in and judgment of Africans’ complicity in the slave trade. He lectures chiefs not to sell their own people and judges those groups that engage in this practice as cowardly or mean.

| (Left; top in mobile) An image of a page of Field Diary II (Livingstone 1866a:[38]). (Right; bottom) An image of a page of Field Diary X (Livingstone 1872h:[89]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. On the page in blue pencil, Livingstone discusses the practices of tatooing and tooth sharpening by an unnamed set of African villagers. The page in gray pencil, in a fashion typical of the field diaries, cycles through a range of topics, among them Livingstone's preparations for sailing on Lake Bangweolo, notes on the conduct of Livingstone's cook Halima, a reference to Livingstone's ill health, and a statement of his hope to complete his travels. |

There are several other ethnographic questions that Livingstone returns to again and again, perhaps from personal curiosity or perhaps because these were open questions in the British imagination of Africa. His consistent observation of tattoos falls into this category, as do his more sparse – but still recurring – observations about possible cannibalism (also see the discussion of this topic in relation to the 1870 Field Diary and the Unyanyembe Journal). Another practice that he disparagingly comments on many times is the habit of abstaining from sexual intercourse during the period a woman is breastfeeding, for up to three years after the birth of a baby.

This last detail is one of the few moments in which Livingstone describes a practice specific to women. It is typical in that women are largely conceived of in their relationship to others, usually as mothers, wives, or sexual partners. There are rare mentions of a particular woman, such as when Livingstone’s cook Halima informs on a man who has stolen some beads. Livingstone adds, “this was so far faithful in her but she has an outrageous tongue,” though it is unclear whether her “outrageous tongue” is a comment on her audacity in this moment or an assessment of her character through repeated exposure (1872h:[89]). For the most part, though, Livingstone’s diaries represent a man’s world, as he travels and lodges exclusively with men during his final journey.

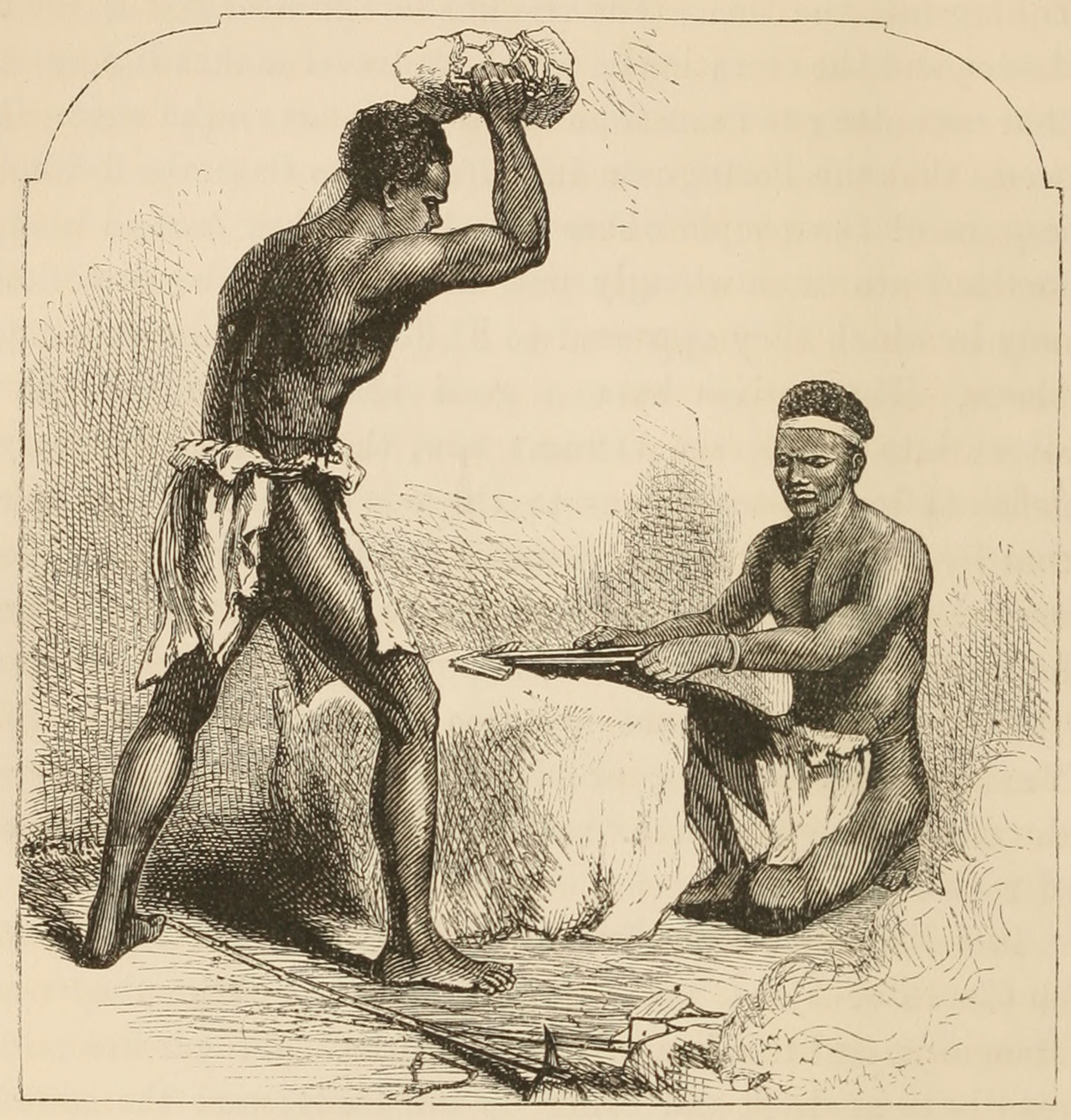

Forging Hoes. Illustration from the Last Journals (Livingstone 1874,1:146). Courtesy of Internet Archive. In the published text, illustrations of local African industrial practices can derive from sketches in Livingstone's diaries or journals, his prose descriptions, or a combination of the two.

When he feels that he has gotten to know an ethnic group, Livingstone attempts to characterize them more abstractly, describing such qualities as a group’s honesty, sympathy, avarice, or cowardice. Often, this comes in the form of comparisons to other groups. For instance, when Livingstone believes the Babisa have deceived him about the availability of food, he writes that they have “no more valour than the others but more craft” (1866f:[18]). This sense of ranking or trade-off of cultures in relation to one another is apparent again when he describes that the “Ketebe or Kapesha [as] very civil and generous” but also adds that the “men [are] very timid,” concluding that it is “no wonder the Arab slaves do as they choose with them” (1872h:[40]). Slavery, again, threads through his ethnographic observations as a reckoning of sorts, an evil that nonetheless tells us much about the individual personalities and cultural norms in which it is practiced.

Livingstone also gestures toward a belief in cultural progress, as when he compares African cultures to Scottish, saying that in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, the Scot became “the apt pupil of more fortunate nations” and from this grew in industry, scholarship, and medicine (1866e:[100]). This sense of development, though, is not absolute, as he adds that the Africans he encounters “are not like our dangerous classes who borrow from civilization little but the art of masking evil & of converting knowledge into cunning” (1866e:92]).

▲ Forms of Representation. Livingstone typically divides each field diary, so that the first two-thirds or three-quarters contain his dated entries, arranged chronologically, and that the final third or quarter is oriented upside-down to the first portion and starts from back to front. In other words, it appears that he develops the two parts a given diary simultaneously – writing one front to back and the other back to front and upside-down relative to the first – so that the two sections meet in the middle. The front section is generally an ongoing record of travel, while the back section usually contains lists, maps, drawings, calculations, and shorter notes. This system thus divides each diary into two parts distinguished by function: narrative (first and longer section), non-narrative collections of observations and information (second and shorter section).

| (Left; top in mobile) An image of a page of Field Diary II (Livingstone 1866a:[41]). (Right; bottom) An image of a page of Field Diary X (Livingstone 1867c:[129]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. |

Though many of Livingstone’s more detailed descriptions of African cultures appear in the narrative sections at the front of the diaries, ethnographic information occupies much of the back section as well, especially in the form of drawings. This implies that Livingstone places importance on the visual aspects of interacting with other cultures and understands this information as different from longer descriptive passages. Often, he uses images to represent the differences he deemed significant between Africans and Europeans in physical appearance.

▲ Philosophical Approach. Since Livingstone does not see himself as an ethnographer, he positions himself as someone whose knowledge is less theoretical, more grounded in practical experiences. Indeed, he believes that “[i]t is a most pernicious error of the Ethnographers that savages are influenced by fear alone,” suggesting that “the Ethnographers” are a separate group, often misled by ideas that do not prove true in practice (1866b:[103]).

This may be connected to a larger concern of Livingstone’s: that he be remembered as a “real” rather than “theoretical” explorer, an idea that he presents in his 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870c:II). A “real” explorer, in these terms, means not just one who spends time on the ground, but also one who has a mindset that oriented toward understanding local languages and cultures. In contrast with “the Ethnographers” above, Livingstone argues for approaching local peoples with curiosity rather than with the intention to inspire fear. Though he may deviate from this in practice, he seems sincerely to believe in the worth of an unbiased approach.

![An image of a page from Livingstone's Notebook III (22 July-7 Oct. 1871:[17]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Images of the Livingstone manuscripts from the David Livingstone Centre are copyright University of Glasgow Photographic Unit. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page from Livingstone's Notebook III (22 July-7 Oct. 1871:[17]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Images of the Livingstone manuscripts from the David Livingstone Centre are copyright University of Glasgow Photographic Unit. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/the-final-field-diaries-general-overview/liv_000022_0017-article.jpg)

An image of a page from Livingstone's Notebook III (22 July-7 Oct. 1871:[17]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Images of the Livingstone manuscripts from the David Livingstone Centre are copyright University of Glasgow Photographic Unit. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. A list of Swahili words from one of the notebooks included in the present edition. Livingstone often records such vocabulary ad hoc in his field diaries, then assembles it more systematically in intermediate documents such as this notebook. The range of words – which includes the terms for shampoo, lion, some cardinal directions, and "meat used in divination" – reflects Livingstone's interests as an explorer plus his attempts to understand the cultural practices of the populations among which he traveled.

As he begins his final journey, he writes these words, perhaps as much as a reminder for himself as for any future explorers: “A foreign people is not to be understood in a short or hurried visit – nor indeed to be appreciated by the oldest inhabitant, unless he will consent to waive all prejudice and live as one of themselves” (1865:[23]). Livingstone sees his field diaries as part of this mission. Though his records are not without prejudice, he indicates that they may be his way of addressing the difficulty of “realiz[ing] the true aspect of the people” and so document his attempts to “learn to respect their hearts” (1865:[23]).

Religion Top⤴

Although Livingstone’s does not formally undertake his final journey as a missionary, religion nonetheless plays a significant role in Livingstone’s interactions with Africans and Arabs, as well as his observations of local cultures. Christianity is also personally motivating to him, as he understands both his geographical exploration and his anti-slavery work as honoring his god and enabling him to withstand the trials of this journey.

▲ From Missionary to Abolitionist and Geographer. As the field diaries reveal, religion occupies a shifting role in Livingstone’s last journey. Since Livingstone is funded as a geographer rather than a missionary, Christianity is in the last journey integrated into Livingstone’s other objectives rather than prioritized. At times, Livingstone sees this integration as furthering missionary work, as when he comments that “An attention to man's happiness & comfort and intellectual advancement in this life is essential for the promotion of his religious life” (1866a:[102]). In this, he underscores the Christianity and civilization doctrine he first imagined in Missionary Travels (1857), arguing for the promotion of European civilization in Africa as a moral good.

Elsewhere, however, we see Livingstone subsuming Christianity into what emerges as the primary goals of his last journey: geographic exploration and the abolition of slavery. In doing so, he maintains his belief that his work in Africa is for the glory of God even in the midst of changing and ambiguous goals for his third journey.

| (Top) An image of a page of Field Diary VII (Livingstone 1866f:[25]), detail. (Center) An image of a page of Field Diary X (Livingstone 1867c:[116]), detail. (Bottom) An image of a page of Field Diary XIV (Livingstone 1871n:[20]), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. New Year's Day entries for, successively (top to bottom), 1867, 1868, and 1872. In each, Livingstone invokes his commitment to his god. |

Each year on New Year’s Day, as well as at low moments, Livingstone recommits himself to his work by making a commitment to his god. For instance, after Henry M. Stanley leaves him in March 1872, Livingstone – who was in low spirits before he met Stanley and suffers a let-down in his absence – pledges on his birthday, “My Jesus, my King, my life, my all = I again dedicate my whole self to thee = accept me and grant O Gracious Father that ere this year is gone I may finish my task = In Jesus name I ask it - Amen, so let it be” (1871n:[48]-[49]). As he has almost every first of January since his journey began, Livingstone prays that he may complete his “task” within the coming year.

Though the task remains unnamed in these prayers, their repetition and his pledge demonstrate the extent to which Livingstone saw his geographic exploration as consistent with his earlier missionary work. Though he is no longer working explicitly toward conversion, he nonetheless sees his presence in Africa as a “task” that he labored at with God’s blessing. For instance, earlier in his final travels, he asks with slightly less urgency, “Almighty & Gracious Father help me to be more profitable this year” (1867c:[116]). Though there is less urgency in this earlier version, there is still the same sense that Livingstone is racing against the clock, as he also asks, “If I am to die this year prepare me for it” (1867c:[116]).

!['Arab & slaveboy carrying his gun.' Illustration from a page of Field Diary XIV (Livingstone 1871n:[99]), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). 'Arab & slaveboy carrying his gun.' Illustration from a page of Field Diary XIV (Livingstone 1871n:[99]), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/the-final-field-diaries-general-overview/liv_000014_0099-article.jpg)

'Arab & slaveboy carrying his gun.' Illustration from a page of Field Diary XIV (Livingstone 1871n:[99]), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported

In addition, Livingstone comes to see his anti-slavery work as a fulfillment of his missionary training. For instance, he reports preaching to the African headman Gombwa’s people that the Bible comments on the “the sin of selling his children.” He warns of a “Future state where all will be judged” and advises them “to expel enemies who came first as slave traders” (1866d:[68]-[69]). In these moments when the opportunity to preach arises, Livingstone increasingly passes over basic tenets of Christianity to preach ideas directly aimed at proving slavery wrong.

In particular, Livingstone targets the African practice of selling other Africans (often prisoners of war, criminals, or those out of favor). He reports that a headman named Kremasusa wants to show Livingstone the result of following this advice: “He was anxious that I should see another village which he now has from following my advice not to sell his people” (1866d:[45]). Though Kremasusa shows no sign that this new practice is religious in nature, Livingstone nonetheless attributes it to his own work in spreading the idea in God’s name.

▲ Comparative Religions. The field diaries also show Livingstone’s interest in comparative religious observation. He is particularly interested in the difference between the Christian belief in conversion and the lack of desire in his Muslim companions to proselytize. To Livingstone, this is a moral failing: “No oriental comprehends the meaning of benefitting the people” (1865:[21]). Later he avers that religion “requires perpetual propagation to attest its genuineness” (1872g:[122])

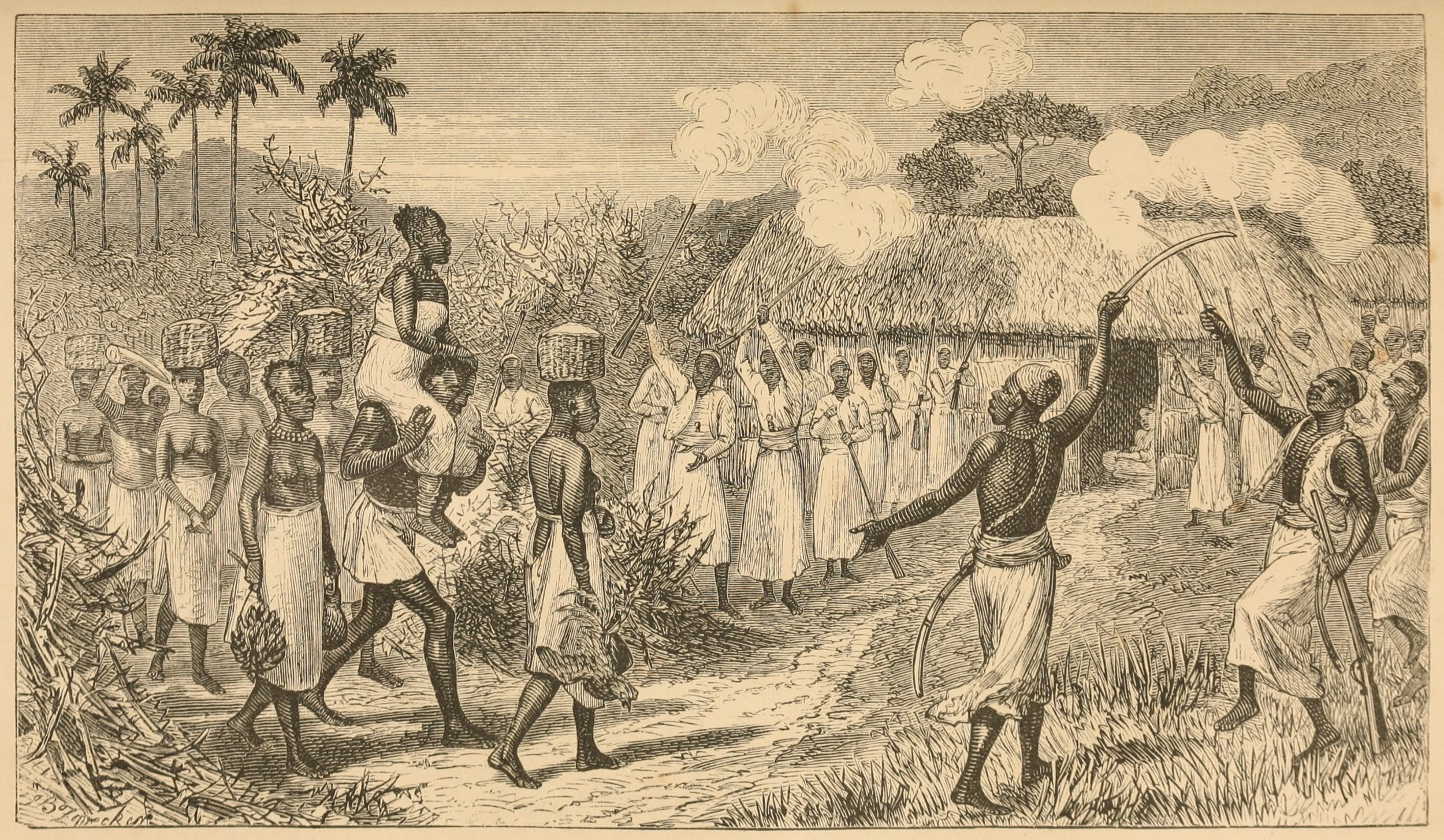

| Lantern Slides from the Life, Adventures, and Work of David Livingstone (Anon. 1900: [28], [14]). Images courtesy of the Smithsonian Libraries, Washington, D.C.. Although he was never a very successful missionary, these slides (which relate to Livingstone's first sojourn in Africa, 1841-56) romanticize Livingstone's efforts at proselytization, imagining what it might have looked like. |

There are signs, though, that Livingstone’s call to proselytize is regarded by others with equal suspicion. When discussing the slave trade with chief Mukate, he reports, “Arabs have told him that our object in capturing slaves was to make them our own slaves and of our own religion” (1866d:[21]). In this, Livingstone records the intersection of several conflicts: the slave trade, vying for locals’ favor, and different understandings of the role of religion.

Livingstone plays his own role in that conflict, often characterizing Islam and other religions as mere superstitions or, worse yet, as hypocritical, as when he records the holdings of brandy and gin by the “Moslems” (1871n:[78]). His assessments of religion are often colored by individual interactions, as when he first meets chief Chitanga and tells him “about God & Bible to which he returned intelligent remarks” (1866f:[83]-[84]). Later, however, after Livingstone and chief have a difference of opinion on an unrelated matter, Livingstone amends this assessment: “it is little that his mind can take in” (1866f:[88]).

The Arrival of Hamees' Bride. Illustration from the Last Journals (Livingstone 1874,1:opposite 232). Courtesy of Internet Archive. Such exoticized cultural illustrations in the published text contrast with the evolving nature of Livingstone's ideas on religion as recorded in his field diaries, particularly in regards to his developing a more comparative perspective on Christianity.

At other points, however, he accepts (sometimes grudgingly) that “They” – in this case, chief Hamees’ people – “seem to be religious in their way” (1867c[23]). In this, Livingstone begins to contextualize Christianity within a wider picture, both geographically and historically, rather than simply reaffirming its superiority. For instance, he observes that in the east, Christianity is a relatively new religion and therefore potentially subversive. It is regarded, he notes, “as many of ourselves do Mormonism” (1865:[20]).

With this, Livingstone also represents religion as a cultural phenomenon. In response to learning that they share a creation story (described as “‘such a one who died’”), he speculates that the Manganja people, as well as other groups situated near Lake Tanganyika and the Zambezi River, “are one & followed the course of great waters going Southwards” (1866d:[25]). In making this connection, he associates religious beliefs with geographic location and ethnic groups rather than with progress toward a single, transcendent truth.

Authority Top⤴

Livingstone occupies a liminal place as an authority figure. On the one hand, he is the leader of his expedition with the power to reward or punish his men as he sees fit. He also shows an implicit belief in his own authority as a white Christian European, sometimes asserting his moral code and belief system as superior to others that he encounters. On the other hand, he is often as the mercy of others’ authority, as when his men threaten to mutiny, local groups clash, or he cannot move forward without forming unsavory alliances. This section attempts to capture the ways that Livingstone’s representations of his authority in his diaries shifts over time and place by exploring Livingstone’s assessment of African leadership in conjunction with his own struggle, both with his porters and as a result of the fallout from violent local conflicts.

▲ African Leadership. Livingstone notes differences in leadership styles as he moves through different regions and among different ethnic groups. These differences are often judged not only through chiefs’ treatment of their own people and other African tribes, but even more frequently through the responses of these individuals to slavery and to Livingstone himself.

Though Livingstone himself often works with Arab slave traders to achieve his own ends, he describes chiefs who appease these same traders as childlike, weak, or scared. For example, Livingstone argues that the chief Chitapangwa has been “spoiled” by his contact with traders (1867f:[83]). With these chiefs, Livingstone sometimes digs in his heels to get what he wants. He seems to see their authority as more malleable in relation to his own, even when the chief in question actually has great power in the situation. Livingstone drives a hard bargain with Chitapangwa, for instance, despite the fact that Chitapangwa threatens to send them back across the Chambezi to famine (1867f:[83]-[84]).

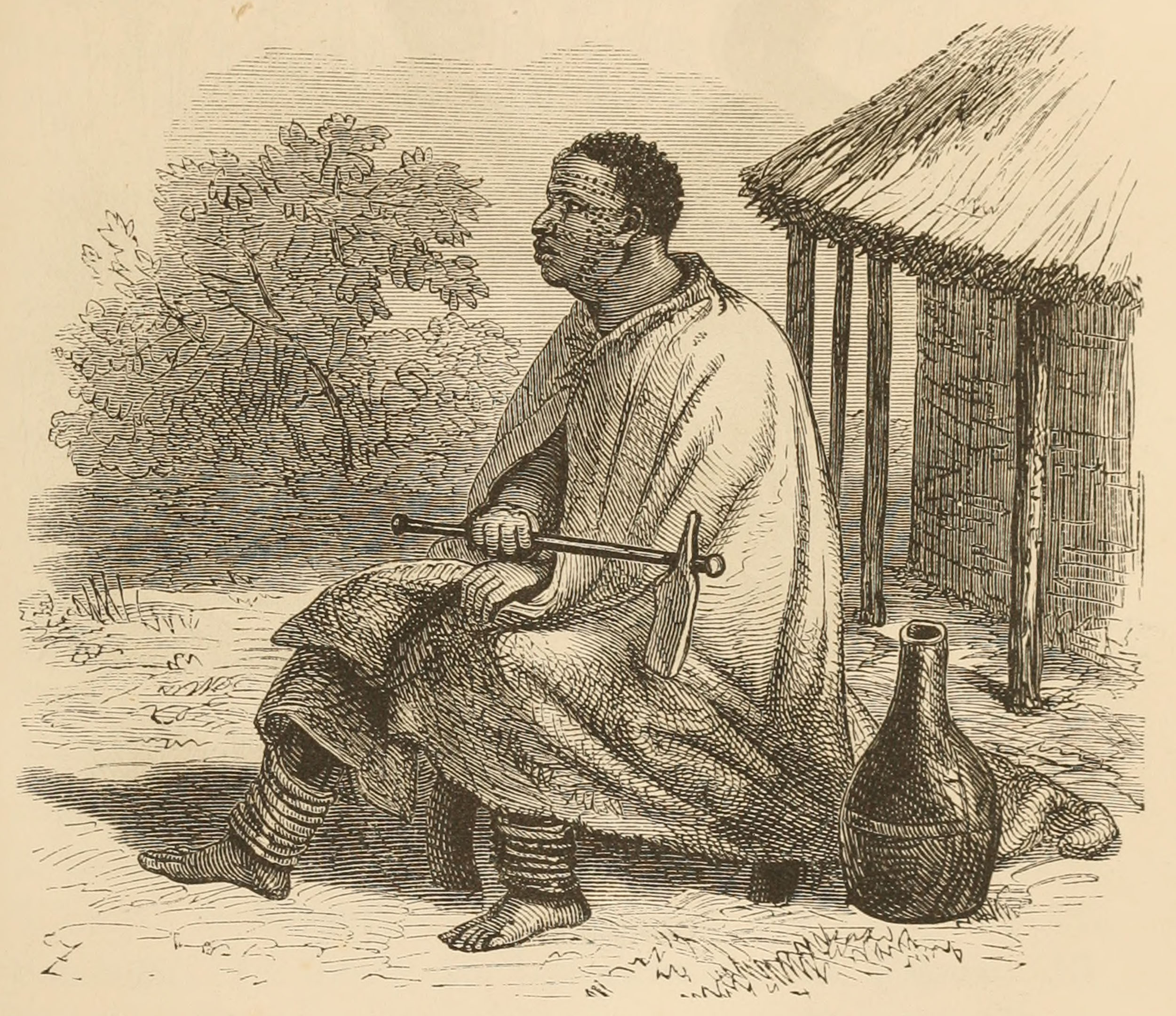

Chitapangwe. Illustration from the Last Journals (Livingstone 1874,1:185). Courtesy of Internet Archive. This representation of Chitapangwa derives from a mixture of Livingstone's sketches of Chitapangwa's facial tattoos and cultural artifacts and the illustrator's own imagination.

With more tyrannical leaders such as the chief Cazembe, Livingstone criticizes their approach as “barbarity” but nonetheless accords them respect (1867c:[85]). He writes admiringly of the “grand reception” Cazembe throws him, evidently seeing this as a rightful recognition of Livingstone’s own importance (1867c:[87]).

Livingstone sometimes presumes to know better than African chiefs what would be good for their people, at least once punishing a villager against the wishes of the headman (1871n:[169]). Livingstone seems to feel justified in this conduct especially when slavery is concerned, as when he enters a village where “some had bought or stolen little children” and Livingstone “order[s] them to be returned.” When “one swore that he did not know from whom he got the child,” Livingstone gives “one blow as a thief & ordered him out of the camp” (1872h:[48]). He seems to feel an authority – religious, racial, ethnic, or a combination of the three – that transcends other hierarchies, as he routinely orders Africans not to engage in buying or selling others.

▲ Troubles with His Men. Livingstone’s judgment of African leadership seems hypocritical when we consider his struggles with his own men. From the beginning, Livingstone struggles with the different ethnic groups that make up his porters, with conflicts arising over language differences and the difficulty of their marches, all intensified by frequent bouts of food scarcity. In describing these conflicts, Livingstone often attributes them to ethnic differences (e.g., the African porters are less “lazy” than the “Nassickers,” a group of freed slaves educated at a school in Nashik, India) (1866c:[52]).

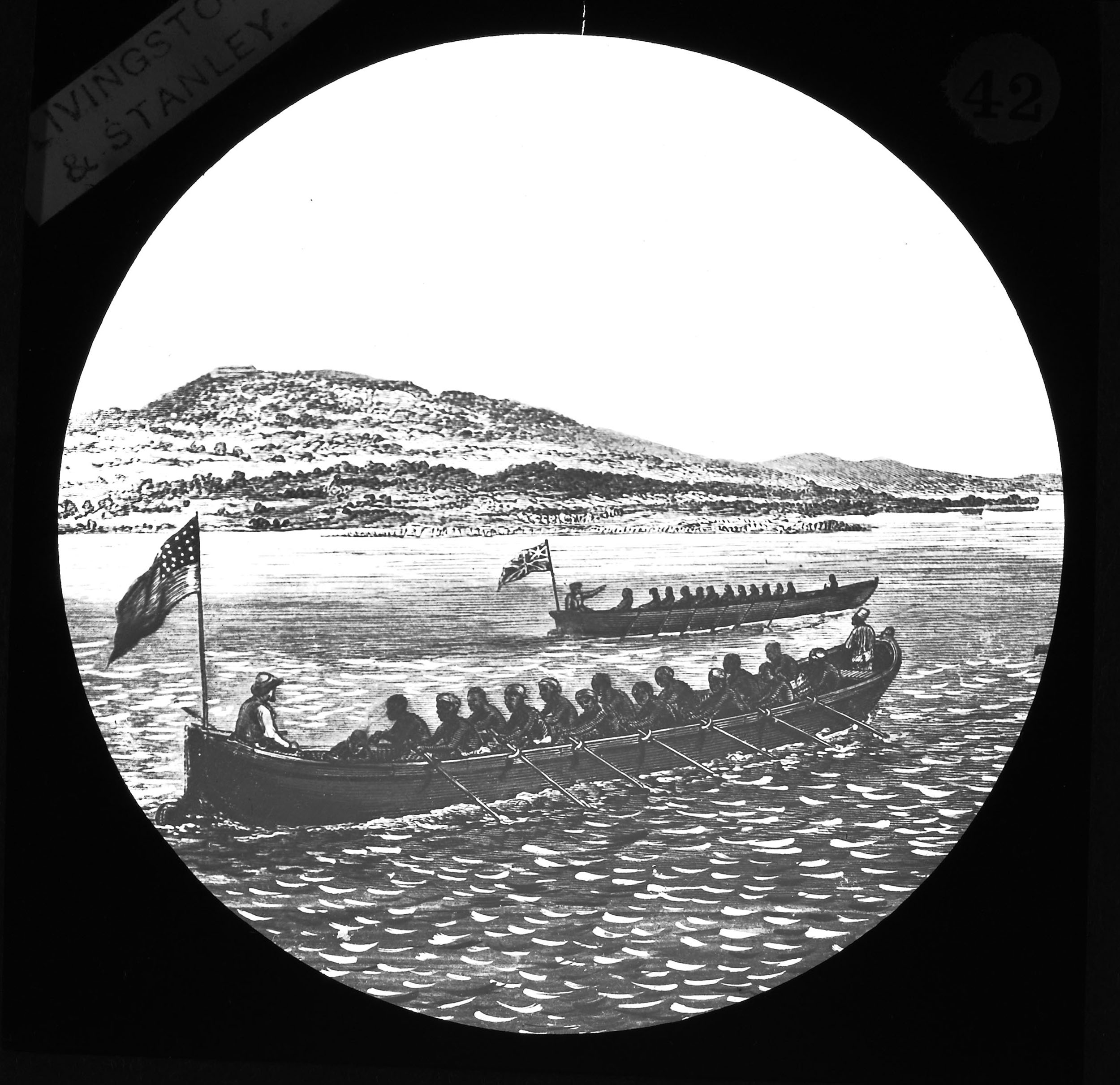

| Magic Lantern Slides: Livingstone and Stanley Series, c.1900. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. The evidence of the field diaries, among documents from Livingstone and others, belies such orderly representations of collaboration between, on one hand, British explorers like Livingstone and Stanley and, on the other, locally-recruited African attendants. |

When mutiny arises from the sepoys (Indian soldiers in the British army), Livingstone feels himself caught between military authorities in India and fear of what the sepoys will do to the Makonde people, fearing that the sepoys will bring “disgrace on the English name” (1866b:[29]). In these instances, Livingstone understands his authority as circumscribed by British hierarchies and values more than by local conflicts. At other moments, however, Livingstone is not afraid to assert his authority through physical punishment, such as caning.

This is not to suggest, however, that Livingstone sees his authority as only arising from punishment. He feels a bond with certain of his men and believes that they serve him out of loyalty rather than fear. For instance, he feels betrayed when his porter Chuma hides his own flour in a time of extreme hunger so as not to share it: “I had always given him a part of any food I got [ . . . ] as a sort of member of my family” (1866f:[47]). These differences in leadership result, not surprisingly, in very different relationships with his men and the duration of their service.

▲ Local Conflicts. In addition, Livingstone tends not to acknowledge the extent to which his authority is intertwined with that of Africans. Good conditions tend to reduce unrest among Livingstone’s men, while tensions flare during times of hunger and hardship. So, a chief or headman who feeds and shelters Livingstone and his men inadvertently reinforces Livingstone’s authority, as he, Livingstone, is less likely to be challenged.

Conversely, local conflicts can circumscribe Livingstone’s authority. The most obvious examples of this are the various relationships between Arab traders and regional African villagers. When traveling with Arab traders, for instance, Livingstone reports that he is barred from contact with Africans: “came to a village stockaded & all the people outside with gates shut - afraid of the Arabs (1867c:[26]).

| (Left; top in mobile) An image of a page of Field Diary XIV (Livingstone 1871n:[89]). (Right; bottom) An image of a page of Field Diary XVI (Livingstone 1872g:[34]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The page wholly in pencil includes a sketch and mechanical description of a faux gun made by boys at Gunda. The page half in pencil and half in brown ink presents part of a list of Livingstone's African porters and an enumeration of the items each carries. Without such lists, which often appear only in Livingstone's field diaries (and not his journals or other manuscripts), many of the names would be lost to history. The load of the last person on the page, Nyaoperi, includes a gun. |

Livingstone also repeatedly notes that the introduction of firearms changes the way that he is treated: “the terror guns have inspired is extreme” (1872h:[46]). Sometimes this means that his own firearms command respect, but more often it means that he cannot barter for food or learn geographical information because he has been prevented from engaging with local peoples.

▲ Fluidity of Authority. Taken together, Livingstone’s writings show how authority is locally constituted and can shift quickly in different situations. Though Livingstone has a bedrock sense of his own authority as a Christian European man, he nonetheless frequently submits to others’ authority, as when he travels with Arabs or avoids the violent conflict with the Mazitu ethnic group.

In 1873, near the end of his life, Livingstone asses his own leadership style thus: “I have gone among the whole population kindly & fairly but I fear that I must now act more rigidly for when they hear that we have submitted to injustice they at once conclude that we are fair game for all” (1872h:[97]). This stems from Livingstone’s firm sense that “submit[ing] to injustice” ruins a person’s integrity and therefore his authority.

![An image of two pages of of Field Diary III (Livingstone 1866b:[48]-[49]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of two pages of of Field Diary III (Livingstone 1866b:[48]-[49]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/the-final-field-diaries-general-overview/liv_000003_0048-0049-article.jpg)

"Outline of Njengo Hill." An image of two pages of of Field Diary III (Livingstone 1866b:[48]-[49]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. An excellent example of the multiple strategies that Livingstone employs to convey his observations of Africa in an authoritative fashion in his field diaries, including drawings, narrative prose, and geographical calculations. One implication of integrated representations such as this one is that each piece of data supplements and reinforces the others.

At the same time, however, Livingstone also records situations in which personal freedom shifts rapidly, as when he engages two “smart young Waiyau men” who had been “bought at Mbanga & Mukate’s by Babisa but the Mazitu killed all their Manganja masters & now they are free” (1866e:[66]). Livingstone believes the Nassickers to be permanently corrupted and unable to command respect because they are former slaves: “some are slaves in spite of all that was done” (1867c:[25]-[26]). Yet, he engages these Waiyau men with the belief that their tenure as slaves is reversible.

Livingstone himself, it seems, clings to the idea that personal qualities such as bravery and a solid work ethic dictate authority as much as or more than circumstances. Ultimately, though, he sees authority as only as good as the ends it achieves. Here, once again, the slave trade influences his practices. Toward the end of his life, he writes that he wishes to complete his geographical quest because “To do all alone will give me an influence and name which I pray may be turned for good in the abolition of this nasty slave trade” (1872g:[29]).

Conclusion Top⤴

The twelve field diaries available in this edition cover a wealth of information beyond the themes traced in this essay, including observations on medicine, politics, Arab culture, and African geography, ecology, and culture. This essay has highlighted some of Livingstone’s most pervasive concerns – ethnography, religion, and authority – as well as demonstrated how Livingstone considers the slave trade in relation to each of these issues. Throughout the field diaries, we can see the tension inherent in Livingstone’s position; the very act of representing African and Arab cultural practices reflects his own cultural position, his biases, and his beliefs. The field diaries are interesting cultural artifacts not only for the information they contain but for the complex representational strategies Livingstone employs.

![John Murray III and Anon., David Livingstone - Boat Scene (Painted Magic Lantern Slide), [1857], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND. John Murray III and Anon., David Livingstone - Boat Scene (Painted Magic Lantern Slide), [1857], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND.](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_014067_0001-carousel.jpg)

![Image of two pages from Livingstone's Field Diary XVI (Livingstone 1872h:[2]-[3]). CC BY-NC 3.0 Image of two pages from Livingstone's Field Diary XVI (Livingstone 1872h:[2]-[3]). CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000016_0003-carousel.jpg)

![David Livingstone, Map of Lakes Nyassa and Shirwa [1864?], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND; Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson, CC BY-NC 3.0 David Livingstone, Map of Lakes Nyassa and Shirwa [1864?], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND; Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson, CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000077_0001-tile.jpg)

![An image of a page of Field Diary II (Livingstone 1866a:[38]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of Field Diary II (Livingstone 1866a:[38]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/the-final-field-diaries-general-overview/liv_000002_0038-article.jpg)

![An image of a page of Field Diary X (Livingstone 1872h:[89]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of Field Diary X (Livingstone 1872h:[89]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/the-final-field-diaries-general-overview/liv_000016_0089-article.jpg)

![An image of a page of Field Diary II (Livingstone 1866a:[41]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of Field Diary II (Livingstone 1866a:[41]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/the-final-field-diaries-general-overview/liv_000002_0041-article.jpg)

![An image of a page of Field Diary X (Livingstone 1867c:[129]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of Field Diary X (Livingstone 1867c:[129]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/the-final-field-diaries-general-overview/liv_000010_0129-article.jpg)

![An image of a page of Field Diary VII (Livingstone 1866f:[25]), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of Field Diary VII (Livingstone 1866f:[25]), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/the-final-field-diaries-general-overview/liv_000007_0025-article.jpg)

![An image of a page of Field Diary X (Livingstone 1867c:[116]), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of Field Diary X (Livingstone 1867c:[116]), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/the-final-field-diaries-general-overview/liv_000010_0116-article.jpg)

![An image of a page of Field Diary XIV (Livingstone 1871n:[20]), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of Field Diary XIV (Livingstone 1871n:[20]), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/the-final-field-diaries-general-overview/liv_000014_0020-article.jpg)

![Inscription on Tree Where David Livingstone's Heart Is Buried. Lantern Slide from the Life, Adventures, and Work of David Livingstone (Anon. 1900: [28]). Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Libraries, Washington, D.C. Inscription on Tree Where David Livingstone's Heart Is Buried. Lantern Slide from the Life, Adventures, and Work of David Livingstone (Anon. 1900: [28]). Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Libraries, Washington, D.C.](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/the-final-field-diaries-general-overview/liv_012010_0028-article.jpg)

![Transporting David Livingstone's Body to the East Coast of Africa. Lantern Slide from the Life, Adventures, and Work of David Livingstone (Anon. 1900: [14]). Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Libraries, Washington, D.C. Transporting David Livingstone's Body to the East Coast of Africa. Lantern Slide from the Life, Adventures, and Work of David Livingstone (Anon. 1900: [14]). Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Libraries, Washington, D.C.](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/the-final-field-diaries-general-overview/liv_012010_0014-article.jpg)

![An image of a page of Field Diary XIV (Livingstone 1871n:[89]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of Field Diary XIV (Livingstone 1871n:[89]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/the-final-field-diaries-general-overview/liv_000014_0089-article.jpg)

![An image of a page of Field Diary XVI (Livingstone 1872g:[34]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of Field Diary XVI (Livingstone 1872g:[34]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/the-final-field-diaries-general-overview/liv_000015_0034-article.jpg)