Livingstone's 1870 Field Diary

Cite edition (MLA): Wisnicki, Adrian S., and Megan Ward, dirs. Livingstone's 1870 Field Diary and Select 1870-1871 Manuscripts. First ed. In Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. University of Maryland Libraries, 2017. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/7fbeae31-b1a8-46f0-9529-67f90d0e36f5.

Cite page (MLA): Wisnicki, Adrian S., and Megan Ward. "Introduction to the Edition." In Livingstone's 1870 Field Diary. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. University of Maryland Libraries, 2017. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/7fbeae31-b1a8-46f0-9529-67f90d0e36f5.

This page introduces our multispectral critical edition of David Livingstone's 1870 Field Diary and select 1870-1871 manuscripts. Livingstone composed these texts over various scraps of paper while stranded in central Africa and used them to capture his first-hand impressions of the central African slave trade, record the complex social dynamics among local populations, and set out geographical information gathered through travel and from Arab and African informants. The text of the 1870 Field Diary, after revision by Livingstone's friend Horace Waller, would eventually become the partial basis of Livingstone's posthumously-published Last Journals (1874). Our edition not only restores Livingstone's original words, but uses advanced spectral imaging technology to recover the hidden material history of the diary and a small set of related manuscripts by revealing the story of their passage through multiple hands and spaces over the last 145 years.

Note: This edition was 1st Runner Up in the DH Awards 2016 for "Best DH data visualization."

|

|

The MLA Committee on Scholarly Editions has awarded Livingstone's 1870 Field Diary and Select 1870-1871 Manuscripts (first edition) the seal designating the edition as an MLA Approved Edition. Awarded: 18 April 2019 |

|

Livingstone's 1870 Field Diary and Select 1870-1871 Manuscripts (first edition) has been has been peer reviewed and approved by NINES. Review date: 2018 |

Introduction to the edition

David Livingstone composed the 1870 Field Diary and a handful or related manuscripts over various scraps of paper while stranded in central Africa. Because of his immobility, Livingstone focused his writing on African life to an extent usual both for his final writings (1866-73) and those of contemporaneous British travelers to Africa. The documents capture Livingstone's first-hand impressions of the central African slave trade, record complex social dynamics among local central African populations, and set out detailed geographical information gathered through travel and by interviewing Arab and African informants.

Livingstone sent some of the manuscripts back to Britain, but carried others – notably the 1870 Field Diary – with him until his death in 1873 in present-day Zambia. Thanks to these vicissitudes, the manuscripts circulated through a variety of environments, passed through multiple hands, and, ultimately, survived to the present day in a handful of archives in Britain. The 1870 Field Diary, like the 1871 Field Diary and significant portions of Livingstone's final manuscripts, would become the basis of Livingstone's Last Journals (1874), the text posthumously edited and published by Livingstone's friend Horace Waller. However, Livingstone's original manuscripts – especially the 1870 Field Diary – bear the unique material traces of a story hidden until now.

This critical edition reveals this story by using advanced spectral imaging technology to recover the production and preservation history of the 1870 Field Diary and a small set of related texts over the last 145 years. In doing so, our edition breaks new ground in the study of David Livingstone's manuscripts and, potentially, those of other nineteenth-century explorers and travel writers, particularly because the edition restores some of the lost hands and voices that helped shape the text as it survives today.

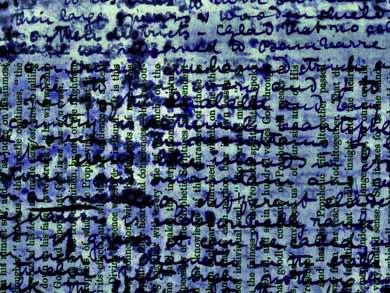

A spectral image of David Livingstone's 1870 Field Diary, second gathering (Livingstone 1870i:LII). Processed to enhance staining. Copyright National Library of Scotland. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The image has been processed to reveal and characterize the extent of the staining.

The edition also represents the culmination of the second phase (2013-17) of the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project. The first phase of the project (2010-13) built on the pioneering work of the Archimedes Palimpsest Project, the Galen Palimpsest Project, and others to demonstrate that spectral image processing could recover faded text composed over nineteenth-century newspaper pages. The second phase takes the technology in a new direction by successfully showing that spectral imaging can also provide significant material information about nineteenth-century manuscripts.

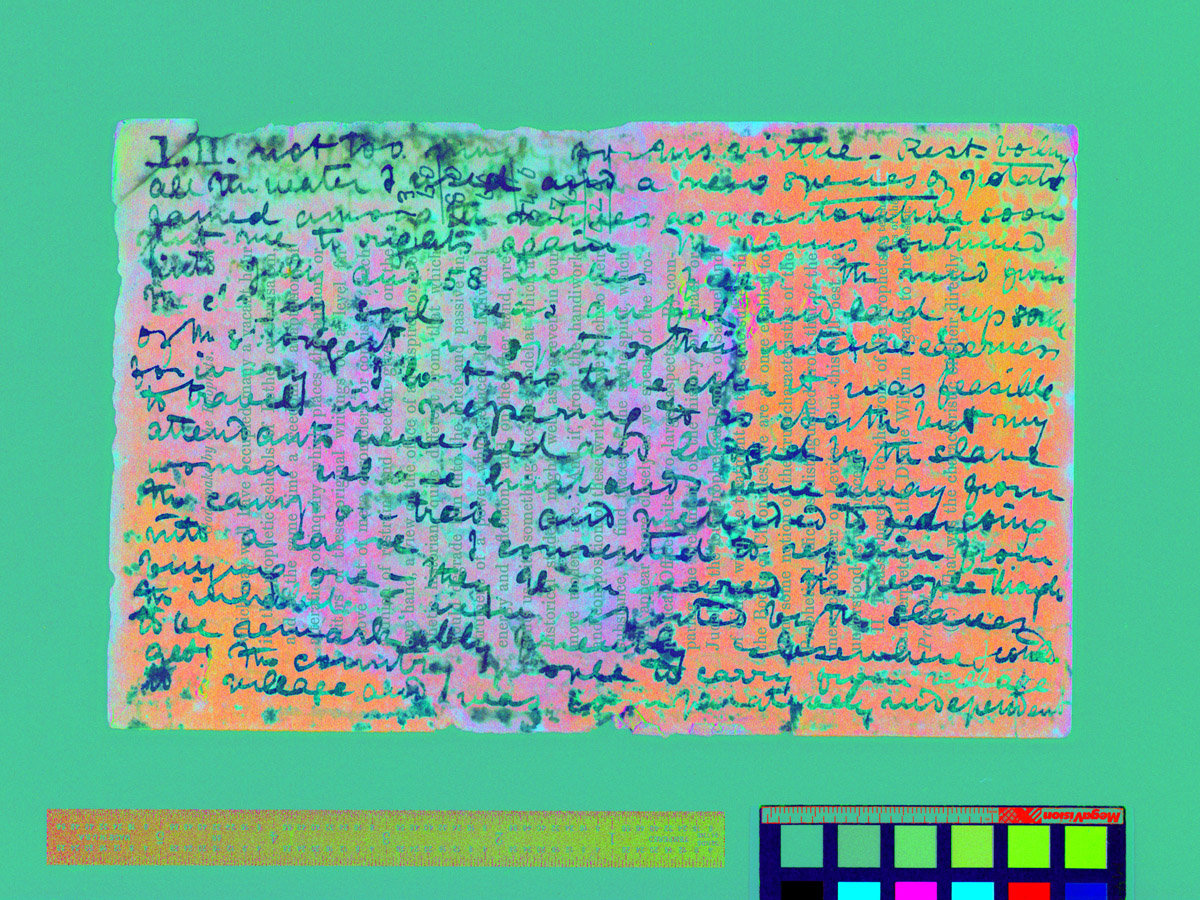

Spectral imaging relies on imaging an object, such as a manuscript, under multiple wavelengths of light, ranging from ultraviolet through the visible color spectrum to the near-infrared. A high-resolution monochromatic digital camera automatically photographs each illumination. Imaging scientists then manipulate this raw image data with computers by applying various processing algorithms with the goal of enhancing features of interest. Often the features are made more visible by creating pseudocolor (false-color) representations of the object that foreground or suppress other object features.

Animated spectral image of four pages from the 1870 Field Diary, second gathering, as written over a leaf from the Pall Mall Budget (Livingstone 1871b:LXXXII color_raking). Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The image shows the relationship between visible page features and underlying folds and creases.

The text of the 1870 Field Diary is not difficult to read with the naked eye and so does not require spectral image processing for legibility like Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary did. Rather a variety of other features make the 1870 Field Diary manuscript worth studying with processed spectral images, including a) Livingstone's decision to construct the diary out of multiple distinct printed and handwritten source texts, b) the presence of diverse inks and pencil marks (from Livingstone and others) on the diary's pages, c) unique elements of manuscript topography tied to events in the life of the diary, and d) environmental traces left on the diary's pages thanks to its complex history.

The second phase of our project, in contrast to the first, has therefore accomplished not one spectral image processing goal (the recovery of lost text), but several while producing a range of new spectral imaging techniques and new processed spectral images. The images offer insights into Livingstone’s creation of his text and the impact of both single moments and long-term processes in determining the manuscript’s current material state. These insights promise to enhance our understanding of the British empire, Victorian travel writing, Livingstone’s biography, and the history of the African cultures among which Livingstone worked and traveled. In using spectral imaging to analyze these features, we hope to open up new possibilities for the technological study of nineteenth-century manuscripts produced by British and other travelers around the globe.

![Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_013723_0001-new-carousel_0.jpg)

![Processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's "Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal" (Livingstone 1870a:[3] pseudo_v4_BY), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's "Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal" (Livingstone 1870a:[3] pseudo_v4_BY), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000211_0003_pseudoBY_940_by_592-carousel.jpg)

![David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, [1869], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland: CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, [1869], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland: CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_003006_0001-new-carousel_0.jpg)