The Diary Across Hands, Space, and Time (3)

Cite page (MLA): Wisnicki, Adrian S., et al. "The Diary Across Hands, Space, and Time (3)." In Livingstone's 1870 Field Diary. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. University of Maryland Libraries, 2017. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/dd8aea19-8bea-44e3-a772-e745848e20f4.

This section continues our analysis of the state of the 1870 Field Diary manuscript by turning to material aspects of the diary closely linked to its travels across hands, space, and time. In particular, the section examines how the many environments through which the diary has circulated have left their marks on its pages. This section also includes a brief discussion of notable material features of the manuscript not covered in the foregoing sections.

The Manuscript Across Environments Top ⤴

– Spectral images most relevant for study of this aspect of the manuscript

Page discolor: ICA_pseudo_1, ICA_pseudo_32, PCA_pseudo_32, PCA_pseudo_34, IC4

The big stain: ICA_pseudo_32, PCA_pseudo_32, PCA_pseudo_34

Blotting and bleed through: pseudo_v4, pseudo_v4_BY, red_green

Brown stains: color, ICA_pseudo_1

Red stains: color, ICA_pseudo_1, IC3, IC4, pseudo_v1, red_green

Miscellaneous singular stains: ICA_pseudo_32, sharpie, IC4

Invisible stains: IC4, IC5

Other material features: color

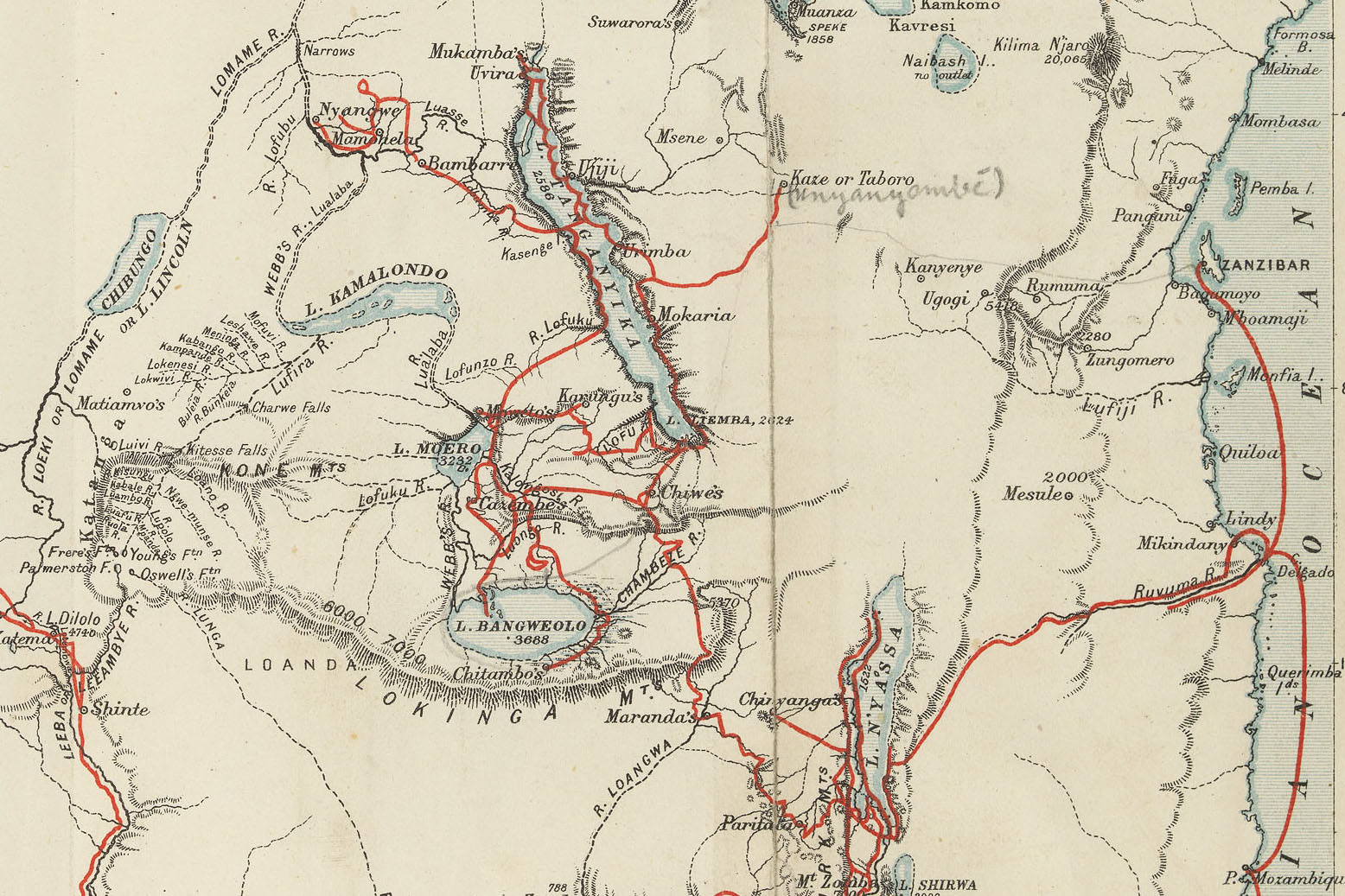

To reach the present day, the 1870 Field Diary passed not only through hands and time, but also space. First, the source texts traveled from Britain (and elsewhere) to central Africa. Next, after Livingstone composed his diary, the manuscript journeyed with Livingstone through the areas of present-day Democratic Republic of the Congo, Tanzania, and Zambia. When Livingstone passed away in 1873, his attendants transported his body along with the diary and other manuscripts to the east coast of Africa and then to Zanzibar.

From Zanzibar, the diary next traveled to Britain, where it further circulated among various individuals while the Last Journals (1874, ed. Horace Waller, pub. John Murray) were in preparation. Finally, Livingstone’s family members distributed the diary’s pages to the three repositories where the different fragments of the diary today reside. To the above, we might also add the travels of the fragments within the three repositories and the journey of the David Livingstone Centre fragments first to Stirling University for conservation in the 1986-87 and then to the National Library of Scotland for spectral imaging in 2010.

Small map from the Last Journals (Livingstone 1874). Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. The map traces Livingstone's final journey across east and central Africa (1866-73). The 1870 Field Diary accompanied Livingstone throughout the latter half of this journey.

Such complex movements across such diverse spaces have left their marks on the diary’s pages. Yet in the majority of cases, it proves impossible to link specific marks to specific places, and it’s not always possible to exclude the chance that some marks are the product of multiple spaces.

Our project also sets limits on understanding the origins of these marks, particularly since our work does not extend from visual analysis of spectral images to, for instance, chemical analysis of the original leaves or to using comparative analysis of the many spectral signatures of the diary’s pages with databases of spectral signatures elsewhere.

As a result, discussion of the diary’s environmental traces must necessarily focus on description of what our project team can observe on the pages (or infer from those observations), with attention to the causes of these traces either limited to certain cases, significantly curtailed, and/or deferred to a future project.

Page Discoloration Top ⤴

Our spectral images of the 1870 Field Diary significantly enhance the visual prominence of page discolor due to wear and/or saturation. The presence of such discoloration can provide a gauge for assessing the relative amount of exposure or short- or long-term handling for a given set of diary pages.

However, drawing the line between discoloration due to wear or saturation or even between either of these factors and lamination (in the case of leaves from the David Livingstone Centre) proves difficult, so divisions between the factors treated in this subsection and the next must necessarily be arbitrary to a degree. That said, even a rough distinction enables us, first, to consider the different environmental factors at play in shaping the diary and, second, to lay potential groundwork for more advanced analysis in the future.

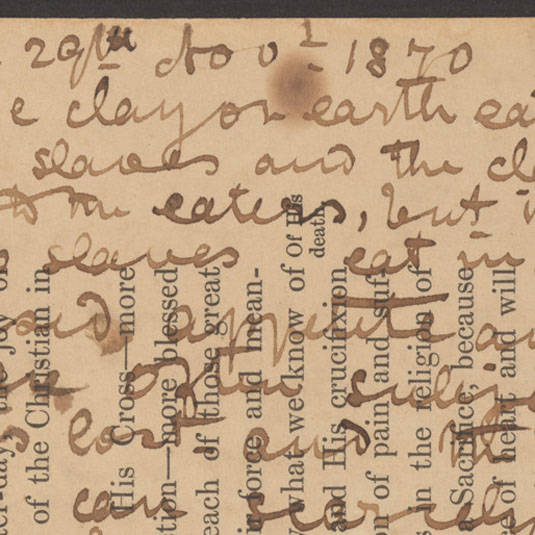

-article-1200.jpg)

A processed spectral image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870i:XXII ICA_pseudo_32). Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The image highlights discoloration along the edges of the page, particularly in the upper left-hand corner where the discoloration coincides with the fading of Livingstone's ink.

In the majority of cases, discoloration covers some portion of either one or more edges of the given diary page or extends from the edges to cover more of the diary page as a whole. Our ICA_pseudo_32 processed spectral images best bring such discoloration to the fore, presenting it as a dark red that notably contrasts with the yellow, not otherwise discolored portions of the page.

When studied alongside the natural light images, the spectral images also reveal that much of the discoloration occurred after Livingstone composed his diary as the patterned fading of his ink in some cases clearly coincides with the areas of the page where discoloration occurs (for a good example of this, see the tops and bottoms of 1870i:XXI-XXXII).

▲ First gathering. In terms of the first gathering (1870b), the discoloration follows one of three patterns, which alternate in a rather random fashion. Either the discoloration covers the whole page almost without exception, or it covers a prominent portion of the page, or it appears along one or more edges of the page.

The first pattern emerges on the very first and last pages of the first gathering (1870b:[1], [70]), and, somewhat inexplicably, on two facing pages near the beginning of the gathering (1870b:[12] and less so on [13]).

![A processed spectral image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870b:[1] ICA_pseudo_32). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). A processed spectral image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870b:[1] ICA_pseudo_32). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/the-diary-across-hands-space-and-time-3/liv_000200_0001_ICA_pseudo_(liv_000205_0032_trans)-article.jpg)

A processed spectral image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870b:[1] ICA_pseudo_32). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. Nearly the entire surface of this page is discolored, as shown by the red coloring in the processed spectral rendering.

The discoloration on the first and last pages (1870b:[1], [70]) might be ascribed to the additional environmental exposure that these pages received because of their position in the gathering. Since one or more leaves of this gathering are missing from the beginning (see Gatherings), it is also clear that this discoloration occurred after the missing leaves became detached.

The discoloration on the two facing pages (1870b:[12], [13]) might be due to the diary being left open here for a longer period of time, as when on display in a museum – although this explanation is speculative.

The second pattern of discoloration covers a significant portion (but not all) of a given page. Examples of this pattern appear along the top and bottom edges of 1870b:[6] (to a lesser degree) and 1870b:[7]; on the right and left edges of, respectively, 1870b:[9] and [10] (the recto and verso of a single leaf), on the right edge of 1870b:[19]; on the right edge of 1870b:[21] (to a lesser degree); and, finally, on the left edge of 1870b:[42].

![A processed spectral image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870b:[9] IC4). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). A processed spectral image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870b:[9] IC4). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/the-diary-across-hands-space-and-time-3/liv_000200_0009_IC4_(liv_000204_0001_trans)-article.jpg)

A processed spectral image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870b:[9] IC4). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The dark edge shows how discoloration can cover a significant portion (but not all) of a given page in the first gathering.

In all of these cases, a clear relationship exists between page discoloration and it size in relation to the pages on either side. More specifically, Livingstone cut all the leaves of this first gathering from the margins of the Quarterly Review essay (see Gatherings) and his pruning resulted in leaves of different sizes. When the leaves are arranged in a stack (as they are in order to constitute the first gathering), the different sizes of the leaves result in considerable portions of some pages being left uncovered by the preceding or succeeding leaf. Those portions left exposed exhibit discoloration.

Examples of the third pattern – discoloration only along one or more edges of the given page – appear much more often in the first gathering than examples of either of the first two patterns. Once more, careful comparative study of the various leaves of the first gathering suggests that the uneven size of Livingstone’s leaves has also produced this sequence of edge discoloration.

As a result, the three patterns of discoloration in the first gathering differ predominantly in their extent on any given page rather than in any specific visual characteristics or, apparently, causal factors.

▲ Second gathering. Because of the additional environmental marks present on the pages of the second gathering, discoloration in this case proves harder to define, to distinguish into patterns, and so, to explain. That the leaves of this gathering are disassembled further compounds the complexity as we can only guess or use reasonable inference to determine how the leaves were once arranged relative to one another.

Some leaves – particularly most of those from the David Livingstone Centre (1870h; 1871a:LXXVI [v.1], less so [LXXVI v.2]; and various pages in 1870j) – exhibit near ubiquitous discoloration. Others, i.e., the majority of leaves from the National Library of Scotland, show discoloration around one or more edges that – depending on the page – can gradually move inward towards the center and imperceptibly blend with what are clearly traces of other substances on the page.

-article-1200.jpg)

A processed spectral image of two bound pages from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870j: LXVII, LXIV PCA_pseudo_34). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The dramatic difference in coloring between these two pages is due to the extensive discoloration of one page (LXVII, top) and not the other (LXIV, bottom).

As a result, the leaves of the second gathering offer little opportunity for causal analysis other than three general, but very rough observations.

1) Nearly all the surviving pages (1870e, 1870f, 1870i:XXI-LV [v.2]) that Livingstone wrote over leaves from the Stanley volume show discoloration along one or more edges, with the discoloration increasingly blending with the prominent central stain that appears later in the second sequence of pages (see The big stain; the blending begins circa 1870i:XLII and increases with each higher numbered page).

That this blending does occur suggests that all of the discoloration on these pages may be due as much to saturation as to exposure or even to a combination of the two. The same applies for all the pages that follow the stain (1870i:LVI-LXI, 1870k, but not 1870j), some of which also exhibit additional, more ubiquitous discoloration that must derive from another source.

-article-1200.jpg)

A processed spectral image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870i:LVI ICA_pseudo_32). Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. On this page, where processing enhances extensive saturation, it is difficult (if not impossible) to distinguish where such saturation ends and where discoloration along the edges of the page begins.

2) The pages that Livingstone wrote over the leaves from the Birdwood article (1871a, 1871b) exhibit a different kind of discoloration, with 1871a:LXXVI [v.1] and 1871b:LXXXVII serving, respectively, as the beginning and end of pages discolored in this way.

1871a:LXXVI [v.1], which is quite discolored throughout, appears on the back of the last leaf of the Birdwood article and would have been more exposed than the pages that follow (see Additional Notes on the Undertexts). 1871b:LXXXVII, the first page of the Birdwood article, would likewise have been exposed because of its place at the head of the article and, not surprisingly, this page too exhibits pervasive discoloration.

The pages that lie between these two endpoints (i.e., 1871a:LXXVI [v.1] and 1871b:LXXXVII) also bear similar, if slightly less pronounced discoloration. In most cases, the discoloration spills from the edges of the page towards the center of the page, exhibits a spectral response rather distinct from what are one or more additional substances on the pages, and in some cases also follows the vertical creasing of the pages (e.g., 1871b:LXXXII, LXXXIV, LXXXVI).

-article-1200.jpg)

A processed spectral image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871b:LXXXII PCA_pseudo_34). Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. This image underscores the highly uneven discoloration of this page, but in particular, in the center, shows how the discoloration follows the vertical creasing of the leaf.

3) The diary pages that Livingstone composed over the leaves of the Pall Mall Budget (1871e) exhibit the least amount of discoloration. These leaves, as preserved today, have been unfolded and flattened, but the discoloration clearly still follows the horizontal and vertical axis of the original folds on these leaves, as especially visible in our ICA_pseudo_1 images. As a result, it is reasonable to conclude that this discoloration occurred at some point before the leaves were flattened.

In addition, this last point also highlights the caution necessary in studying any element of the diary because of the potentially invisible impact that different stage in the diary’s history may have had on the manuscript’s present state of preservation.

-article.jpg)

A processed spectral image of two pages from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871e:C, CI), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The image offers a close-up view of the manner in which the discoloration follows the original folds of this newspaper leaf.

Stains on the Page Top ⤴

Whereas page discolor represents the end result of a longer term environmental process, staining – at least in the case of the 1870 Field Diary – appears tied to more instantaneous events. In particular, the manuscript of the diary shows that at specific moments Livingstone and/or others spilled various substances on the diary pages. In some cases, these substances – definitive identification of which lies outside the means of the present project team – interfere with Livingstone’s handwritten text; in other cases, these substances lie below or over the text. The variety of stains and their impact on the visual characteristics of the 1870 Field Diary represent some of the most defining features of the manuscript.

▲ The big stain. This stain divides into two distinct segments: Visual inspection of the 1870 Field Diary coupled with reasonable inference suggests that at some point someone left the manuscript of the diary open at 1870i:LV [v.2] and LVI. This moment occurred after Livingstone had written his entries up to at least 1870i:LXI (the end of the letter to Lord Stanley, dated 15 November 1870), but before he passed away (see Reinking and Revision).

Indeed, it’s possible that Livingstone himself had the manuscript open as he was copying over the letter to Lord Stanley, a circumstance that would also suggest that he first drafted the letter in his diary, then used that draft to produce the final version which he actually sent (Letter to Stanley) – although these points move decidedly into the realm of conjecture.

When open, the relevant pages of the diary either covered the preceding stack of leaves (1870i:LV [v.2]) or the succeeding stack (1870i:LVI). Twine looped through the lower left-hand corner of 1870i:LV [v.2] may have held the former stack of leaves together, while the other stack was not bound, at least not in a way that is evident today (see Fourth sub-gathering). Finally, it seems that while open, the two stacks were arranged contiguously, 1870i:LV [v.2] farther from the reader and 1870i:LVI closer.

![An animated spectral image (ASI) of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870i:LV [v.1]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An animated spectral image (ASI) of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870i:LV [v.1]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/the-diary-across-hands-space-and-time-3/liv_000205_0035_big-stain_fast-webpage.gif)

An animated spectral image (ASI) of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870i:LV [v.1]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The ASI combines a variety of individual processed spectral images in order to demonstrate the material complexity of the big stain.

While the manuscript occupied this state, someone spilled a liquid (water?) all over it, thereby heavily saturating the pages (1870i:XXXVII-LV [v.2] and, separately, 1870i:LVI-LXI). Our spectral images, which distinctly foreground the impact of this event (see PCA_pseudo_32, PCA_pseudo_34, and especially ICA_pseudo_32), enable review of the process of saturation at a level of detail not possible via the natural light images.

The water saturated all of 1870i:LVI in a fairly even pattern, then seeped through to the succeeding leaves, in an ever diminishing fashion, so that by page 1870i:LXI the water’s effects are minimal. The saturation caused the surface (recto) ink of 1870i:LVI to blot, the verso ink to bleed through to the recto (and vice-versa), and this process of blotting and bleed through to repeat on a lesser scale on the subsequent pages. (Note: Our pseudo_v4 and pseudo_v4_BY spectral images considerably diminish the effect of the blotting and bleed through, while the red_green images maximize the effect of the bleed through.)

The proximity of the two stacks of leaves at this moment proves hard to discern, but evidence suggests that the stacks were in closer contact on the left side than the right. As the water saturated 1870i:LVI, it also cascaded off the top of the page, then seeped between 1870i:LII and LIII of the other stack, heavily saturating them via a trajectory that started off-center at the edge of each of the pages (1870i:LII and LIII), then moved across the pages towards center of them.

![A spectral image animation of a sequence of pages from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870i:XXXIX-LV [v.2], even-numbered pages only). Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). A spectral image animation of a sequence of pages from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870i:XXXIX-LV [v.2], even-numbered pages only). Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/the-diary-across-hands-space-and-time-3/liv_000205_0019-0036_verso_color_1.0-webpage.gif)

A spectral image animation of a sequence of pages from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870i:XXXIX-LV [v.2], even-numbered pages only). Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The animation demonstrates how saturation related to the big stain spread through successive pages of the diary. The animation of the odd-numbered pages in this sequence appears in our Notes on Processed Spectral Images.

That trajectory has today left a stain on those pages in the shape of a comet with a rounded head at near the top of the pages (where the saturation stopped) and a wide tail at the bottom (where the saturation began as it seeped between the pages). Once between these two pages (1870i:LII and LIII), the water seeped upward through the stack to 1870i:LV [v.2] and downward all the way to 1870i:XXXVI, ultimately resulting in a kind of blotting and bleed-through of handwritten text similar to that seen on the stack of leaves covered by 1870i:LVI.

Although we suspect that this saturation is related both to the the large hole that runs concurrently with the first stack of pages (1870i:XXXVI-LV [v.2]; see Manuscript Holes) and to the circular impression on 1870i:XXXV/XXXVI (see Page Impressions), which stands at the head of the page sequence in question, we lack the evidence to prove this conclusively. Other questions also remain, including how we might account for the fact that the saturation occurred between two pages, one of which is the last to include the hole for twine, while the other has no such hole and, indeed, marks the start of a new set of source text pages.

▲ Brown stains. The 1870 Field Diary bears a handful of other stain in addition to its most prominent stain. These additional stains decidedly represent secondary phenomena. Their characteristics prevent any kind of inference regarding the substances that made the stains or the causal relationship between the stains (if any), but study of each of the stain types does enable us to make a few remarks about them.

| A segment of four processed spectral images of a single page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871b:LXXVIII color, PCA_pseudo_32, ICA_pseudo_1, and IC4), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The images demonstrate how each processing technique can reveal different characteristics of a given stain on the page, in this case the first kind of brown stain cited in this section. |

For instance, the 1870 Field Diary includes at least two different sets of brown stains, which seem not to be ink because their color often contrasts with the handwritten ink on the given page. One set appears on the right-hand side of 1871b:LXXVIII-LXXXVII (i.e., nearly all the leaves from the Birdwood article). Our ICA_pseudo_1 processed spectral images best bring these stains to the fore and present them as an irregular, dark orange or deep red blot.

These stains have seeped into the leaves from the edge of the page, where their mark is widest, then the stains narrow to a point as they move towards the center of the page. To a degree, these stains distort Livingstone’s writing and so may have occurred after he composed his entries. However, the evidence is inconclusive on this point, and it’s also possible that the presence of the stains on the page prevented the normal absorption of Livingstone’s ink into the page.

| A segment of two processed spectral images of a single page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870j:LXIII color, ICA_pseudo_1) Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The processing applied to the image at right (bottom in mobile) helps detail the distribution of the brown staining on the page. |

The second set of brown stains appears throughout the pages of the second gathering, and its presence follows no discernible pattern (instances appear on 1870e, 1870i:XXI-XXII, 1870j, 1871a:LXXVI [v.1], 1871e). The ICA_pseudo_1 images also best bring out this type of stain, whose color ranges between dark orange, fiery orange, and bright yellow in the processed images.

These brown stains, in contrast to the other set, generally takes a circular or roughly oval form and clearly occurred by a substance falling on the page from above. The stains can appear anywhere on the page and are generally small in size (equivalent to one or two of Livingstone’s handwritten characters). The stains have no visible impact on Livingstone’s ink, and careful examination of the natural light images suggests that the stains lie below the ink and so pre-date it (for an exception see page 1871a:LXXVI [v.1]).

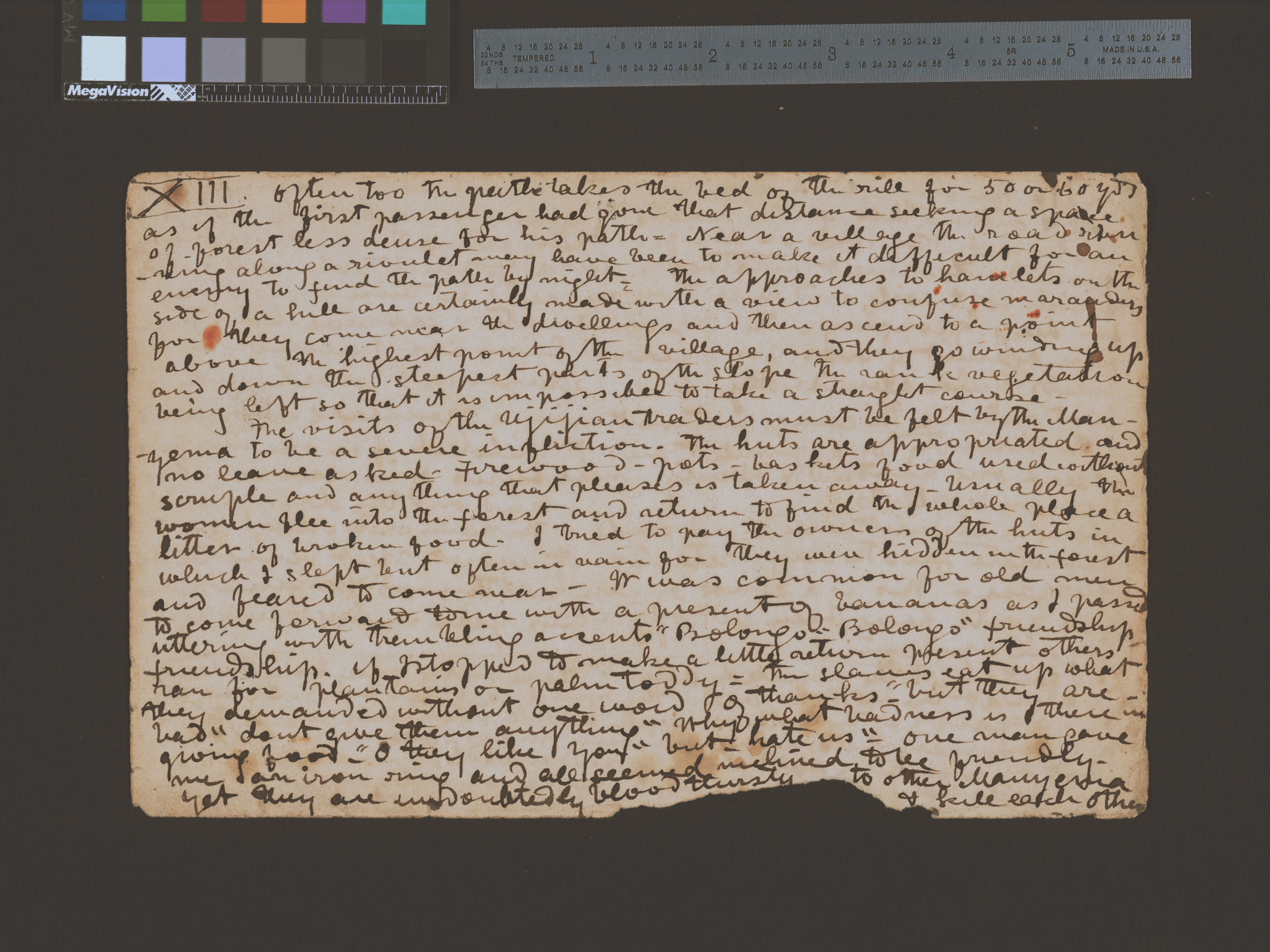

▲ Red stains. In addition to the brown stains, the 1870 Field Diary also contains at least one set of red stains. The red stains are even more common, with instances visible in both the first gathering (1870b:[1]-[4], [37]-[42], [55], [57], [59], [67]-[70]) and the second (1870e; 1870i:XXI-XXIV, XXXIII-XXXIV, XLIII-XLIV, LI-LVII, LX-LXI; 1870j; 1871a; 1871b:LXXVIII-LXXIX). In natural light, the stains take on a dark, rusty red color, while in ICA_pseudo_1 renderings they appear a solid red-orange shading into dark gray.

The red stains tend to be small, even smaller than the second set of brown stains (which, incidentally, often appear on the same pages as the red stains), and are of a circular character, which again suggests that some substance falling on the page produced the stains. The red stains also do not seem to have any impact on Livingstone’s ink and, again, seem to lie beneath the ink, at least as rendered in our images.

A processed spectral image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870e:XIII). Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. In this natural light image, a prominent red stain is visible on the left side of the page, but a series of less pronounced red stains also appears on the right.

▲ Miscellaneous singular stains. Beyond the brown and red stains, the 1870 Field Diary also includes a handful of singular stains. Three such stains are present on page 1871a:LXXVI [v.1] to the left and right of page center. Two of the stains clearly lie below the writing (and have no impact on it), are about the size or a quarter or silver dollar, circular (though the one at left has a series of jagged, star-like edges and so appears to have splattered on the page), and are either light brown (left stain) or faint orange (right stain) in natural light.

![A processed spectral image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871a:LXXVI [v.1] PCA_pseudo_34). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). A processed spectral image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871a:LXXVI [v.1] PCA_pseudo_34). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/the-diary-across-hands-space-and-time-3/liv_000208_0001_PCA_pseudo_(liv_000205_0034_stats)-article-1200.jpg)

A processed spectral image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871a:LXXVI [v.1] PCA_pseudo_34). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. This processed image illuminates and helps differentiate the diverse singular stains that appear on this page. An animated spectral image that highlights these stains appears in our essay on Prototyping Animated Spectral Images (ASIs).

The character of the third stain, which appears quite prominently in the upper left-hand corner of the page, differs considerably in that the stains is rectangular, jagged, very dark (dark brown to black), and completely covers and so hides Livingstone’s handwritten text. This stain resembles no other on the pages of the 1870 Field Diary.

A further set of unusual stains can be found on 1870h:XX. These stains run along the left, right, and bottom edges of the page, and vary in color and shape from elongated, asymmetrical orange-brown ovals (left-hand side) to progressively fainter and more jagged light brown circles (right-hand side).

A processed spectral image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870h:XX red_green), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The processing of this spectral image shows that, although the prominent stains here cluster together, their composition differs and, as a result, that they may be due to very different sets of causes or circumstances.

Indeed, due to the variations in character, the stains may signal the presence of multiple substances and embody the end results of a more complex material history, as some of the stains clearly lie over Livingstone’s handwritten text and distort it, while others do not. (Note: Two long, yellowish stains appears in the left margin of pages II and III, but a lack of spectral images for these pages prevents further study of the stains.)

▲ Invisible stains. Our processed spectral images have also revealed a series of remarkable stains that are not visible to the naked eye, at least through study of the natural light images, and, indeed, went previously unsuspected by the project team until discovered by chance when pursuing another spectral image processing objective. The stains are all present on or in the vicinity of page 1870h:XVII (one of the pages Livingstone composed on the back of Baker’s map) and are visible in either one or the other of two monochromatic processed images, IC4 and IC5.

| Two processed spectral images of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870h:XVII IC4, IC5). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. Each of these images reveals stains, of an unknown cause, that are not visible under natural light. |

One such stain, on IC5, appears to the left center of the page, is of an elongated cigar-like shape, and of a darkness comparable (at least in this rendering) to that of Livingstone’s handwritten text. The other, more dramatic set of stains can be seen in the IC4 rendering as a series of larger drops, darker at the edges than in the middle, ranging in size from quarter to dime, and arranged in a curving vertical line along the lower half of the page.

Although the project team can provide no further information about these invisible stains, their unexpected presence of the page in question points to a material history of the 1870 Field Diary as yet only glimpsed and so opens new frontiers for study of the diary’s pages.

Other Material Features Top ⤴

In closing, three additional material features of the 1870 Field Diary require brief, additional comments. These features, which all relate to the construction of the diary or its source texts, do not fall into any of the other categories above.

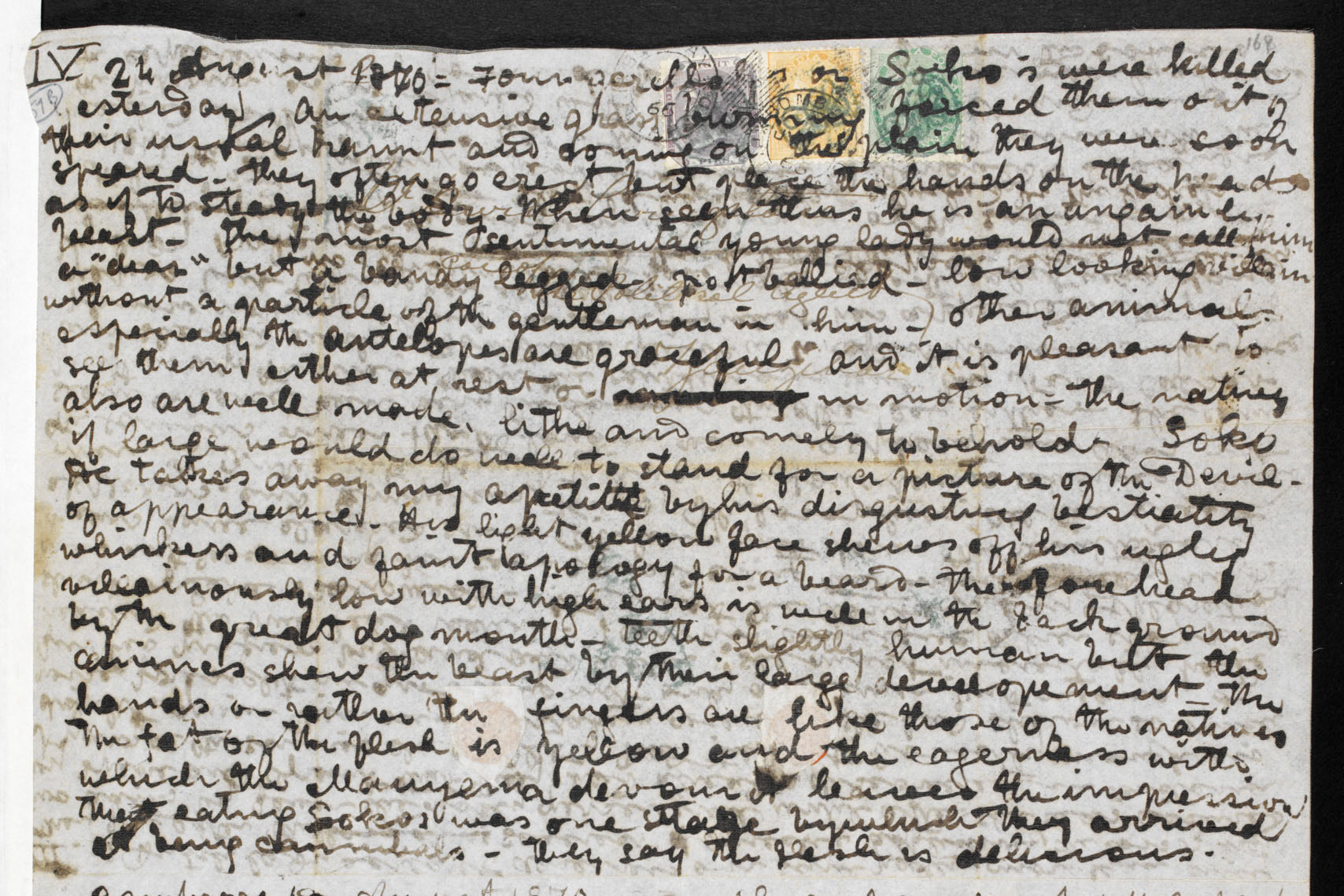

First, the first gathering of the 1870 Field Diary (1870b) remains bound with twine. The twine, of course, can be studied in person at the David Livingstone Centre, where this gathering today resides, but also appears in the images of one page (1870b:[70]) plus in a recent photograph (2015) taken by one of the members of our project team of the diary on display in a museum case at the Centre (see Gatherings). This last photograph also shows the diverse sizes of the leaves of this gathering when stacked on top of one another and so supports the point made earlier about page discoloration in the first gathering due to the exposure of various pages or parts of pages (see First Gathering).

An image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870b:IV), detail. Image copyright British Library Board, Shelfmark Add. MS. 50184, 169r. Used by permission. Livingstone wrote this page of the 1870 Field Diary over a letter that, as seen here, still retains the original stamps used to send the letter to Livingstone in the first place.

Second, 1870c:IV, one of the four pages written over the letter from Gorbello[?], still retains the original three rectangular stamps (red, yellow, and green) used to mail the letter to Livingstone. There are also two postmarks over these stamps, both from Bombay and dated “[18]65” and “[18]66.”

Finally, the gutter edge of 1870i:XLVII and XLVIII still includes a segment of, apparently, the green adhesive that originally held these pages in the bound Stanley volume.

*

Like ink and pencil marks on the page and elements of manuscript topography, environmental traces on the pages of the 1870 Field Diary provide insights into both unique moments and longer-term processes that have helped configuring this diary as it exists today. In the final part of this essay, we outline the previously documented history of the manuscript, then integrate the findings set out in this multi-part essay to produce a comprehensive new chronology of the diary.

![Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_013723_0001-new-carousel_0.jpg)

![Processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's "Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal" (Livingstone 1870a:[3] pseudo_v4_BY), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's "Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal" (Livingstone 1870a:[3] pseudo_v4_BY), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000211_0003_pseudoBY_940_by_592-carousel.jpg)

![David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, [1869], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland: CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, [1869], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland: CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_003006_0001-new-carousel_0.jpg)

-article.jpg)

-article.jpg)

-article.jpg)

-article.jpg)

-article.jpg)

-article.jpg)