History & Chronology of the 1870 Field Diary

Cite page (MLA): Wisnicki, Adrian S., et al. "History & Chronology of the 1870 Field Diary." In Livingstone's 1870 Field Diary. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. University of Maryland Libraries, 2017. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/24ea361b-e744-409f-a28d-ae041994cf81.

This section concludes our analysis of the state of the 1870 Field Diary manuscript by summarizing the previously documented history of the diary and by using our findings in the foregoing parts of this essay to develop a comprehensive new chronology of the manuscript.

Introduction Top ⤴

The pages of the 1870 Field Diary record the long and complex history of this fascinating manuscript, one of the most visually arresting and textually intriguing documents produced by British nineteenth-century travel in Africa.

Until the work of the present project team, this history has remained largely unknown.

However, recourse to existing documentation, close analysis of the manuscript, reasonable inference, and, most importantly, use of advanced spectral imaging technology have now enabled us to recover and reconstruct the diary’s history in a detailed and comprehensive manner.

![Animated spectral image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary, second gathering (Livingstone 1871a:LXXVI [v.1]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). Animated spectral image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary, second gathering (Livingstone 1871a:LXXVI [v.1]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/history-chronology-the-1870-field-diary/liv_000208_0001_reverse-layers_fast-webpage.gif)

Animated spectral image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary, second gathering (Livingstone 1871a:LXXVI [v.1]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The animation combines a variety of spectral images to demonstrate how Livingstone built up layers of text on the page.

This section concludes our analysis of the state of the 1870 Field Diary manuscript by summarizing the previously documented history of the 1870 Field Diary and by using our findings in the other parts of this essay to develop a comprehensive new chronology of the manuscript that relies on the evidence of the diary pages themselves – in other words, a chronology that underscores the considerable potential of spectral imaging technology to expand our understanding of Livingstone’s diary and, potentially, those of other nineteenth-century British travel writers.

Previously Documented History of the 1870 Field Diary Top ⤴

The first phase of the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project (2010-13) documented most of the known history of the 1870 Field Diary (a.k.a. Bambarre Field Diary) along with that of the 1871 Field Diary (a.k.a. Nyangwe Field Diary), both of which might also be grouped under a single heading (Manyema Field Diary). As a result, that history need not be repeated here other than a brief recap and, as relevant, the addition of a few bits of information specific to the 1870 Field Diary.

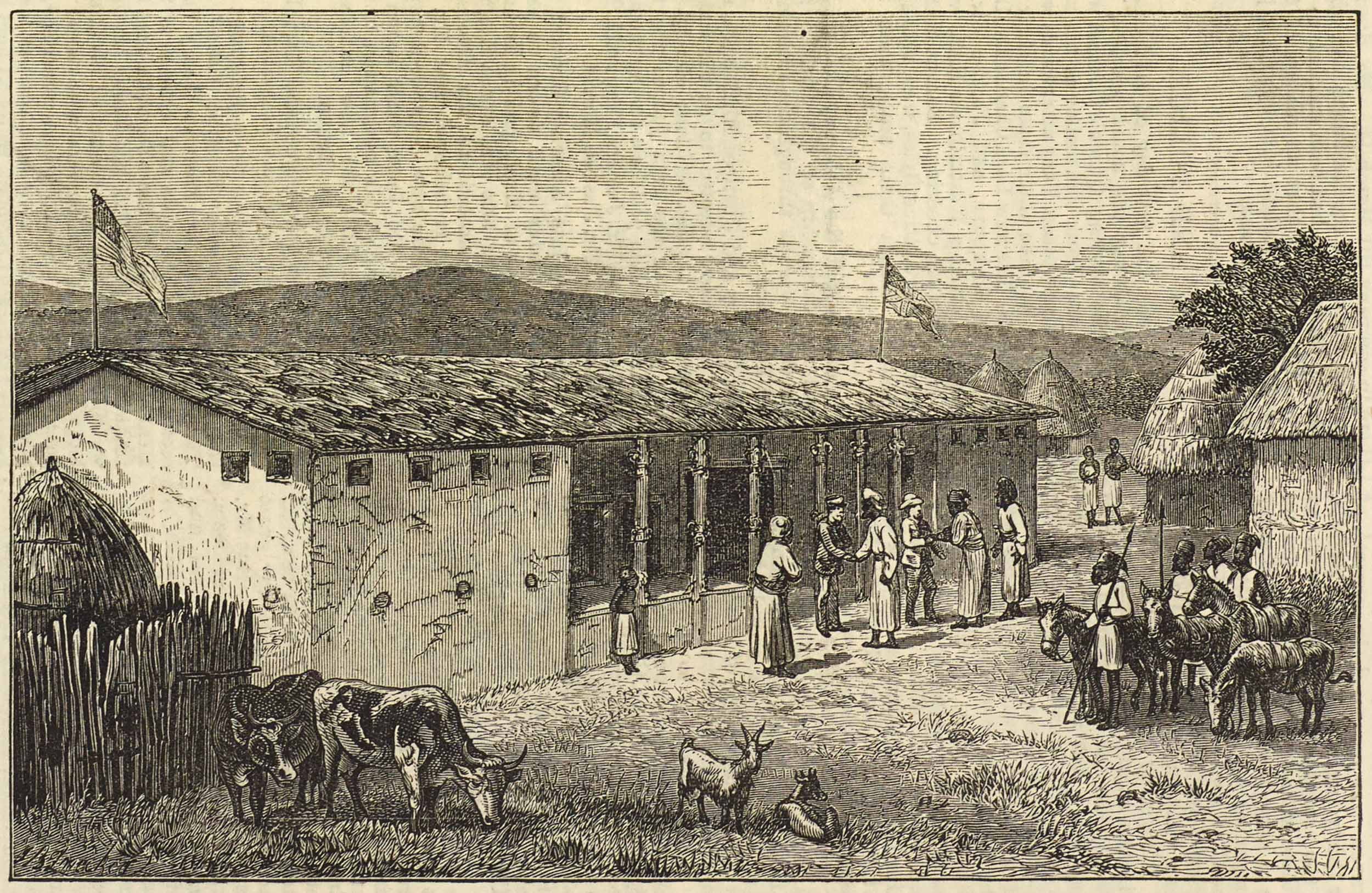

Roughly speaking, the field diaries and journals from Livingstone final expedition (1866-73) followed one of three trajectories before their arrival in Britain. Livingstone entrusted the massive Unyanyembe Journal (1866-72) to Henry Morton Stanley in March 1872, and Stanley carried that journal back to Britain where it became the basis for Horace Waller’s edition of the Last Journals (1874). Livingstone kept another fourteen field diaries from the final expedition (field diaries I-XIII [1866-71] plus one from a previous expedition) in a box at Ujiji, where the British explorer Verney Lovett Cameron recovered them in February 1874, after Livingstone’s death. These arrived too late to be of use to Waller. Finally, Livingstone carried the 1870 and 1871 Field Diaries plus a handful of other diaries (field diaries XIV-XVII [1871-73]) with him until his death in present-day Zambia in 1873. These diaries also accompanied Livingstone’s body back to Britain.

"Visit of Arabs to Livingstone and Stanley at Unyanyembe," from a review of Henry M. Stanley's "How I Found Livingstone," Illustrated London News, 20 (1872), 485. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. It was in Unyanyembe that Livingstone parted with Stanley and entrusted to him the massive journal that now bears the name of the village.

Once back in Britain, the 1870 Field Diary (and at least a part of the 1871 Field Diary) passed to Livingstone’s daughter Agnes. Agnes then transcribed these materials – including portions of the 1870 Field Diary that seem no longer to survive in the original (Livingstone 1870d, 1870g) – for Horace Waller, Livingstone’s friend and editor, who later recognized her efforts (Waller, in Livingstone 1874,1:iv). Agnes’s handwritten transcription was typeset, revised, and soon became the basis for the relevant portion of the Last Journals. Recourse to the 1870 Field Diary, in this case, occurred in part because the diary – in contrast to Livingstone’s other final field diaries – offers a more detailed account of the given period than the Unyanyembe Journal, which Waller usually used in the first instance.

After preparation and publication of the Last Journals, the pages of the 1870 Field Diary passed to the Livingstone family, where they were held, apparently, before being distributed to various repositories. The first four pages of the second gathering (Livingstone 1870c), for instance, remained with the branch of the Livingstone family that descends from Agnes Livingstone and that includes Diana Livingstone Bruce, great-granddaughter of David Livingstone. Diana Livingstone Bruce gifted these pages (along with a variety of Livingstone letters addressed to Agnes, Mary Moffat [Agnes’s mother and Livingstone’s wife], and Robert Moffat [Agnes’s maternal grandfather]) to the British Library in 1960, where the pages have remained ever since.

The British Library, 2015. Copyright Angela Aliff. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported

Another set of pages (Livingstone 1870e, 1870i, 1870k, 1871b, 1871e, i.e., the bulk of the pages) passed to the branch of the Livingstone family that descends from Anna Mary Livingstone Wilson, another Livingstone daughter, and that includes Hubert F. Wilson, Livingstone’s grandson. The latter deposited these pages, along with 68 letters and the first draft of part of Livingstone’s first book Missionary Travels (1857), with the National Library of Scotland in 1965. The Livingstone family then subsequently donated these pages of the library, where these pages have since remained.

Finally, the remaining pages (Livingstone 1870b, 1870f, 1870h, 1870j, 1871a) have a more complex history, as already detailed by the first phase of the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project. These pages also passed to the Wilson branch of the Livingstone family, and this branch gifted them to the Scottish National Memorial to David Livingstone (now the David Livingstone Centre) on one more or more uncertain dates between the end of the 1920s and the period directly after World War II.

The pages then remained at the Centre until at least 1975; traveled to the National Library of Scotland in the late 1970s, where they were copied as part of the Livingstone Documentation Project; were erroneously handed off to the John Murray archive in London; then returned to the Centre at some indefinite point, probably in the early 1980s.

Adrian S. Wisnicki, director of the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project, in the archives of the David Livingstone Centre, 2015. Copyright Angela Aliff. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported

From the Centre, the pages made one final trip in March 1986 to Stirling University for conversation, returned to the Centre in May 1987, and then disappeared from view until rediscovered by Centre’s archivist Anne Martin in 2009 due to a research request from Adrian S. Wisnicki, director of the present critical edition.

Finally, in 2010, the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project brought together nearly all the known pages of the 1870 Field Diary (and the 1871 Field Diary for that matter) at the National Library of Scotland for a two-week period. Here the project team spectrally imaged all the pages, plus a number of contemporaneous letters. These images form the basis of the present critical edition.

A New Chronology of the Manuscript, 1863-2017 Top ⤴

1863-1870

- Prior to his last journey (1866-73), Livingstone obtained at least two of the printed texts (see 1870a and 1870e/1870i/1870j/1870k) that he would assemble into the 1870 Field Diary. The second of these texts dates to 1863, but it is unknown when Livingstone acquired his copy.

- Individuals other than Livingstone wrote on and folded two of the source texts (see 1870c, 1870h) that would eventually become part of the 1870 Field Diary, then sent these documents to Livingstone in central Africa. This process included the addition of stamps and postmarks to the first of these.

- Individuals other than Livingstone folded or otherwise assembled two other printed source texts (1871a/1871b and 1871e), then also sent these on to Livingstone in Africa.

- Livingstone received the handwritten and printed texts cited above while traveling in central Africa during his last expedition (1866-73), the last of the texts (1871e) potentially arriving in February 1871 along with the copy of The Standard over which Livingstone wrote the 1871 Field Diary (see 1871f).

- Livingstone read and, in one case, used gray then red pencil to annotate one of the source texts (see 1870e/1870i/1870j/1870k).

- Livingstone used a smattering of other source text pages for various ad hoc calculations and maps made in pencil and brown and black iron gall ink.

- As Livingstone made his ad hoc notes, he (or perhaps one or more individuals who handled the relevant texts before him) also dropped or spilled various unknown substances onto the leaves of the texts. Today these substances appear as brown, red, and other stains (some not visible to the naked eye) beneath Livingstone’s handwritten 1870 Field Diary text.

-article-1200.jpg)

Processed spectral image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870e:X ICA_pseudo_1). Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The processing highlights the circular staining (at left) of unknown origin.

1870-1873

- Livingstone composed and revised the 1870 Field Diary by writing his entries over the source texts.

- He carried out this work (presumably) between 1870 and 1871.

- The work included a complex process of constructing the diary out of the source texts.

- Livingstone did all this composition and revision work in various shades of brown iron gall ink.

- As part of the composition process, Livingstone wrote around some pre-existing page folds and tears in the pages.

- He used some page folds to structure the placement of his handwritten text on the page.

- Livingstone also did not necessarily compose the diary pages in strict numerical or chronological sequence. He numbered some pages in advance of writing on them and returned to other pages after he had written on them to make both minor and major additions or revisions.

- Livingstone assembled the first gathering of the 1870 Field Diary (1870b) into a booklet and bound it with a piece of twine that survives to the present day.

- Livingstone also, apparently, used twine looped through a sequence of pages from the second gathering (1870i:XXI-LV) to hold those pages together, although that twine does not survive and the pages are today unbound.

- At some point, something made a faint oval impression on multiple pages of the second gathering of the diary (1870e, 1870i, 1870j, 1870k, 1871a, 1871b). This impression may be due to the interaction of printed ink on the page and humidity in the African environment or may be the result of a paperweight that Livingstone used to hold down his pages as he wrote.

- The diary suffered damage when someone saturated a series of pages from the second gathering (1870i:XXXVII-LXI) with what appears to be water. This saturation resulted in the blotting, bleed through, and pronounced staining of long sections of Livingstone’s text.

- Livingstone sought to counter the saturation damage by reinking some of the most smeared text first with iron gall ink, then, at a point after early April 1871, Zingifure ink.

- Concurrently with reinking and revising portions of the diary in Zingifure ink, Livingstone also wrote a full page of the diary (1870h:XX) in this ink.

-article.jpg)

Processed spectral image of a particularly saturated page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870i:LVII IC4), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The processing dramatically reveals Livingstone's reinking, at a later date, of one of the most smeared words on the page.

1873-1874

- The diary received additional damage, including additional saturation from a circular object being set on one of its pages (1870i:XXXV-XXXVI) and the puncturing of a sequence of pages with a sharp or blunt object (1870i:XXXV-LV [v.2]). These event may or may not have a connection with the other major instance of page saturation cited above, but Livingstone did not attempt to remedy this damage either by reinking or by repairing the pierced pages, and so the damage may have occurred after his death in April 1873.

- One or more additional substances were spilled on the pages of the diary, now falling on top of Livingstone’s handwritten text so as to smear or otherwise obscure that text. Livingstone did not attempt to remedy this damage either so it too may have occurred after his death in April 1873.

- The edges of a few pages of the 1870 Field Diary (1870k:LXXIV, LXXV) were torn off, taking Livingstone writing with them. Again, Livingstone did not restore this writing, so this damage too may have occurred after his death.

- As the manuscript of the 1870 Field Diary aged and circulated through various kinds of environments, its pages started to become discolored in various places.

- The manuscript of 1870 Field Diary accompanied Livingstone’s body and some of his other final field diaries (including the 1871 Field Diary) from central Africa to Britain.

- Once in Britain, the 1870 Field Diary along with other diaries and journals from Livingstone final expedition to Africa became the basis for the Last Journals (1874) edited by Horace Waller. Agnes Livingstone transcribed the 1870 Field Diary manuscript as part of this process.

1874-1965

- Different branches of the Livingstone family took possession of different portions of the 1870 Field Diary manuscript.

- Sections of the manuscript passed from the Livingstone family to the David Livingstone Centre (circa late 1920s-late 1940s), the British Library (1960), and the National Library of Scotland (1965).

- Archivists and others at the three repositories added a few annotations, a shelfmark, and archival page numbers to the manuscript’s leaves.

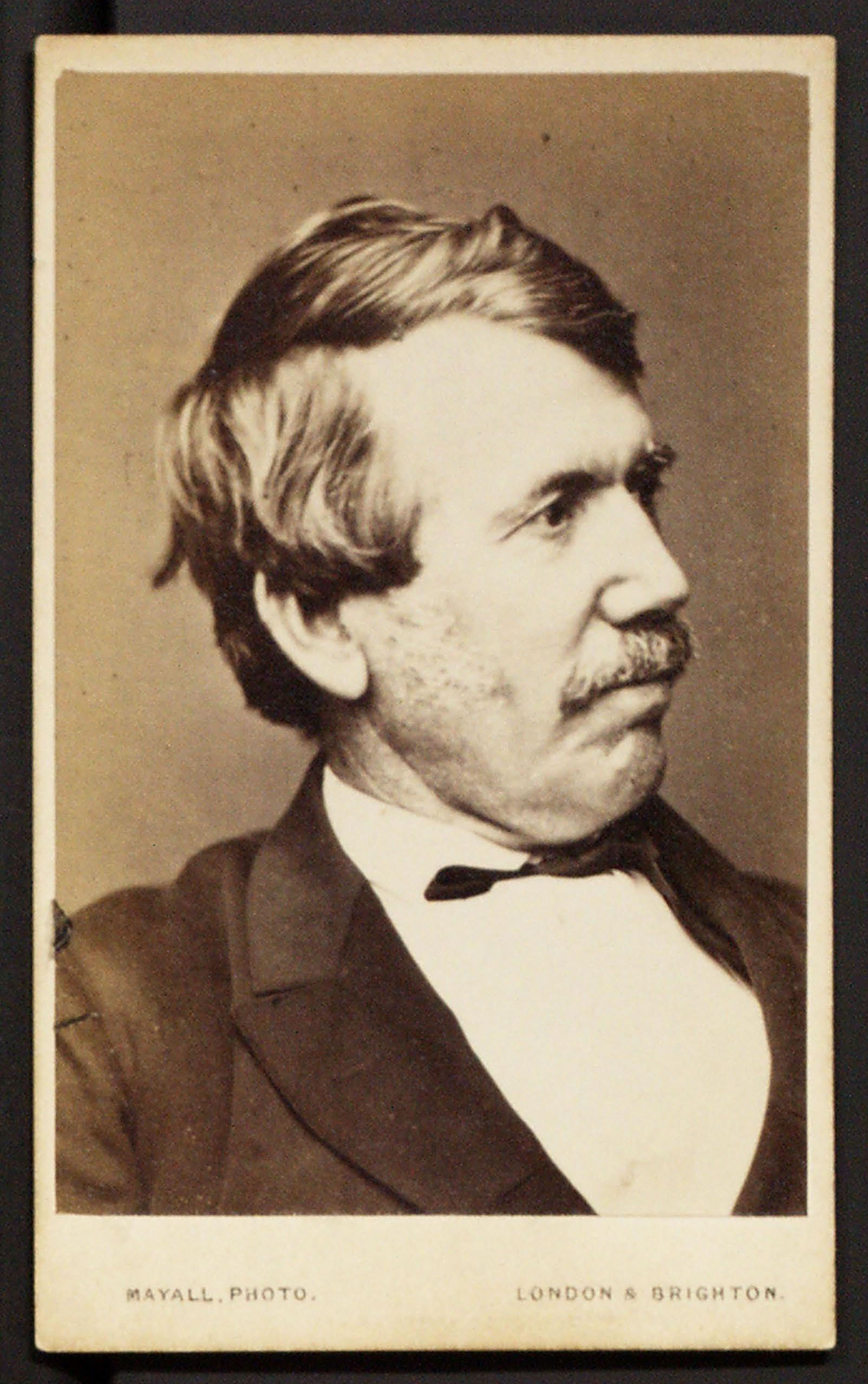

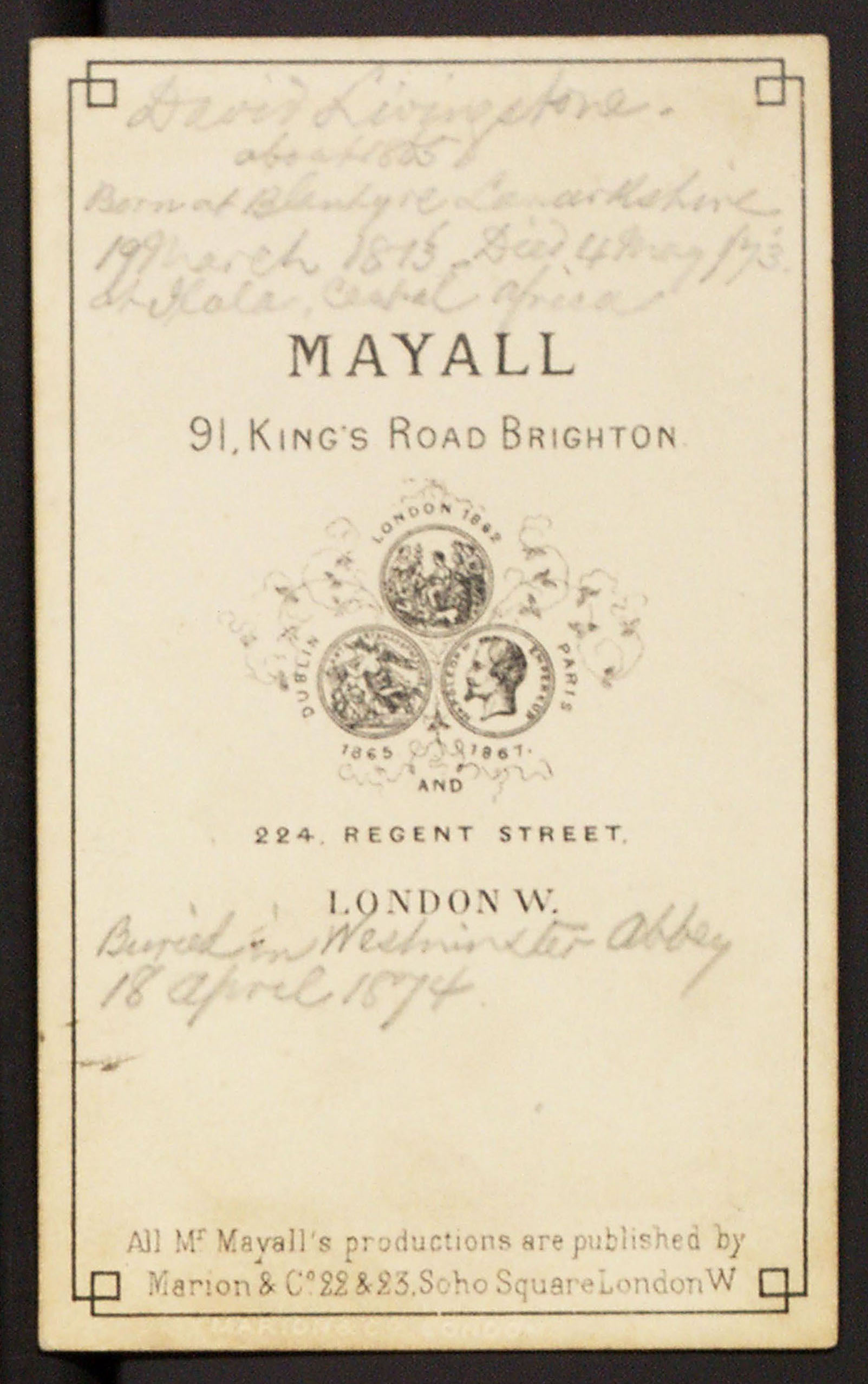

| Mayall, Carte de visit with portrait of David Livingstone, date unknown (no later than 1865), recto and verso. Images courtesy of the Smithsonian Libraries, Washington, D.C. The image on this card may be one of the last known photographs of Livingstone before he left for his final journey. |

1965-2008

- The three repositories, in various forms, arranged for the diary’s conservation. The conservation work included flattening out some of the diary’s leaves and, in some cases, laminating them. Stirling University carried out the conservation work on the David Livingstone Centre pages between March 1986 and May 1987.

2009-2017

- In 2009, the David Livingstone Centre’s archivist Anne Martin rediscovered the Centre’s segments of the 1870 Field Diary while following up on a research query from Adrian S. Wisnicki.

- In 2010, the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project arranged for further conservation of the David Livingstone Centre leaves of the diary (particularly so that the most fragile bits could be stabilized), then spectrally imaged all of the diary except for the four pages held by the British Library. These spectral images form the basis of the present critical edition.

The present critical edition (2017), therefore, represents the last step in this historical sequence. The edition adds one final repository to the list, Livingstone Online, and brings together all the surviving the pages of the diary for the first time in over a hundred years.

![Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_013723_0001-new-carousel_0.jpg)

![Processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's "Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal" (Livingstone 1870a:[3] pseudo_v4_BY), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's "Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal" (Livingstone 1870a:[3] pseudo_v4_BY), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000211_0003_pseudoBY_940_by_592-carousel.jpg)

![David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, [1869], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland: CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, [1869], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland: CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_003006_0001-new-carousel_0.jpg)