The Diary Across Hands, Space, and Time (2)

Cite page (MLA): Wisnicki, Adrian S., et al. "The Diary Across Hands, Space, and Time (2)." In Livingstone's 1870 Field Diary. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. University of Maryland Libraries, 2017. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/6851b824-bc16-4acf-8629-ab1ee03fce0d.

This section continues our analysis of the state of the 1870 Field Diary manuscript by turning to material aspects of the diary closely linked to its travels across hands, space, and time. In particular, this section uses manuscript topography as a means to illuminate how handling by a variety of individuals has helped shape the present material state of the manuscript.

Handling the Manuscript Pages Top⤴

– Spectral images most relevant for study of this aspect of the manuscript:

Folds: raking, color_raking, IC3

Impressions: color, raking, color_raking, IC3

Torn pages: color, raking, IC3

Holes: raking, color_raking, IC3

Several factors limit the study of the original 1870 Field Diary manuscript leaves. First, the leaves, often out of sequence, reside in several repositories. This makes comparative side by side study impossible, both among different segments of text (for instance, the first and second gatherings) and within different segments (e.g., all the pages in the second gathering written over the leaves from Stanley).

Additionally, many leaves have been laminated or otherwise flattened in a manner that has potentially transformed – in non-trivial ways – key material characteristics of the leaves such as page folds or impressions (for instance, the leaves from the David Livingstone Centre and the British Library).

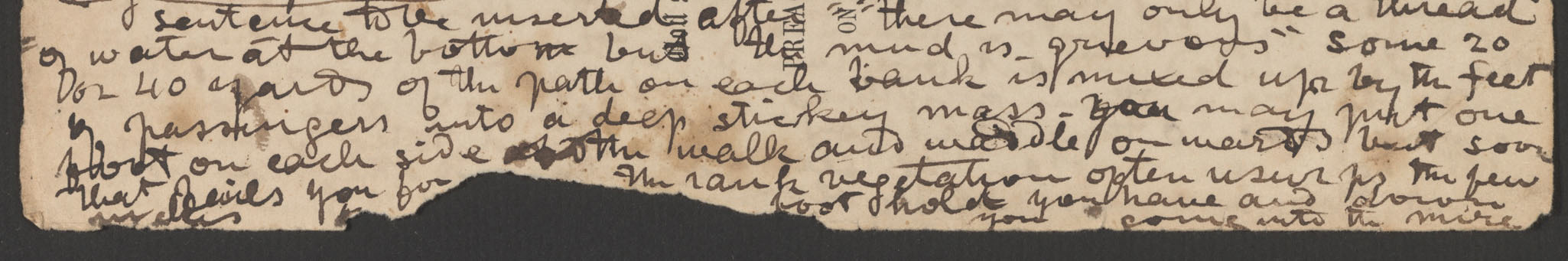

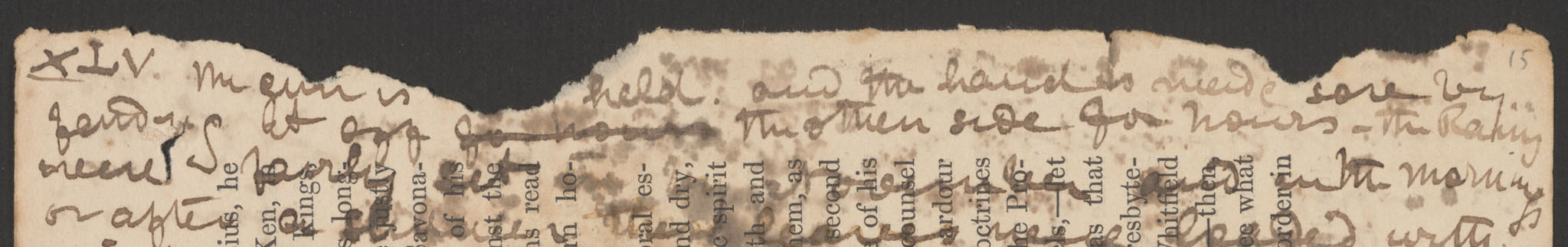

An image of page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870h:XIX), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. This page has been laminated with a heat-set document repair tissue that has begun to fray at the edges.

Finally, the leaves at the National Library of Scotland are today encased in archival quality polyester film that prevents direct handling of the pages and dramatically circumscribes options for studying manuscript topography, as members of the project team found when examining these leaves in 2015.

Fortunately, the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project has been able to apply a number of strategies to surmount these limitations. First, we were able to arrange for the National Library Scotland leaves to be removed from their sleeves for imaging. To create those images, we used high-resolution photography rather than scanning, which could further flatten the leaves.

An animated spectral image (ASI) of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870i:LIII color_raking). Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The animation alternates between a color image and a raking light image and shows elements of page topography not visible under natural light (i.e., the color image), thereby foregrounding the relationship of these topographical elements to the handwritten text and staining on the page.

In addition, our workflow also included using raking spectral image lights. Such raking lights illuminate the given manuscript page at oblique angles (i.e., from the sides rather than from above) and so, in our case, have allowed for producing processed 3D spectral image reconstructions of page topography from raw 2D spectral images.

These processed raking light images offer an extraordinary window onto page topography, or the collection of folds, impression, holes, and other features inscribed on the surface of the page - often beneath the printed and handwritten text. This enables us, in turn, to examine material manuscript features that are obscured in the originals or that might pass unnoticed for other reasons, such as creases being too faint to see with the naked eye or page discoloration impeding study of page impressions.

As a result, in the following subsections we explore the handling of Livingstone’s manuscript over time through such features as folds, impressions, holes, and torn pages.

Page Folds Top⤴

The history of the manuscript pages of Livingstone’s 1870 Field Diary begins outside of Africa, in Britain and wherever else the paper was produced and where the original source texts were printed or handwritten on the pages. This history helps account for the topography of the manuscript pages today, both for those pages that are relatively flat (because they originally formed part of a bound volume) and those that have been folded due to the original publication format.

Attention to original format offers the potential to help scholars distinguish between “original” folds (i.e., folds introduced as part of the process of creating the texts prior to Livingstone’s handling of them) and folds introduced later in the manuscript’s history, whether by Livingstone or someone else.

▲Original folds. Livingstone’s source texts might be divided into two groups: those that have folds consistent with potential expectations for those texts (1870b, 1870e/1870f/1870i/1870j/1870k, 1870h, 1871e) and those that do not allow for easy assumptions about their “original” state (1870c, 1871a/1871b).

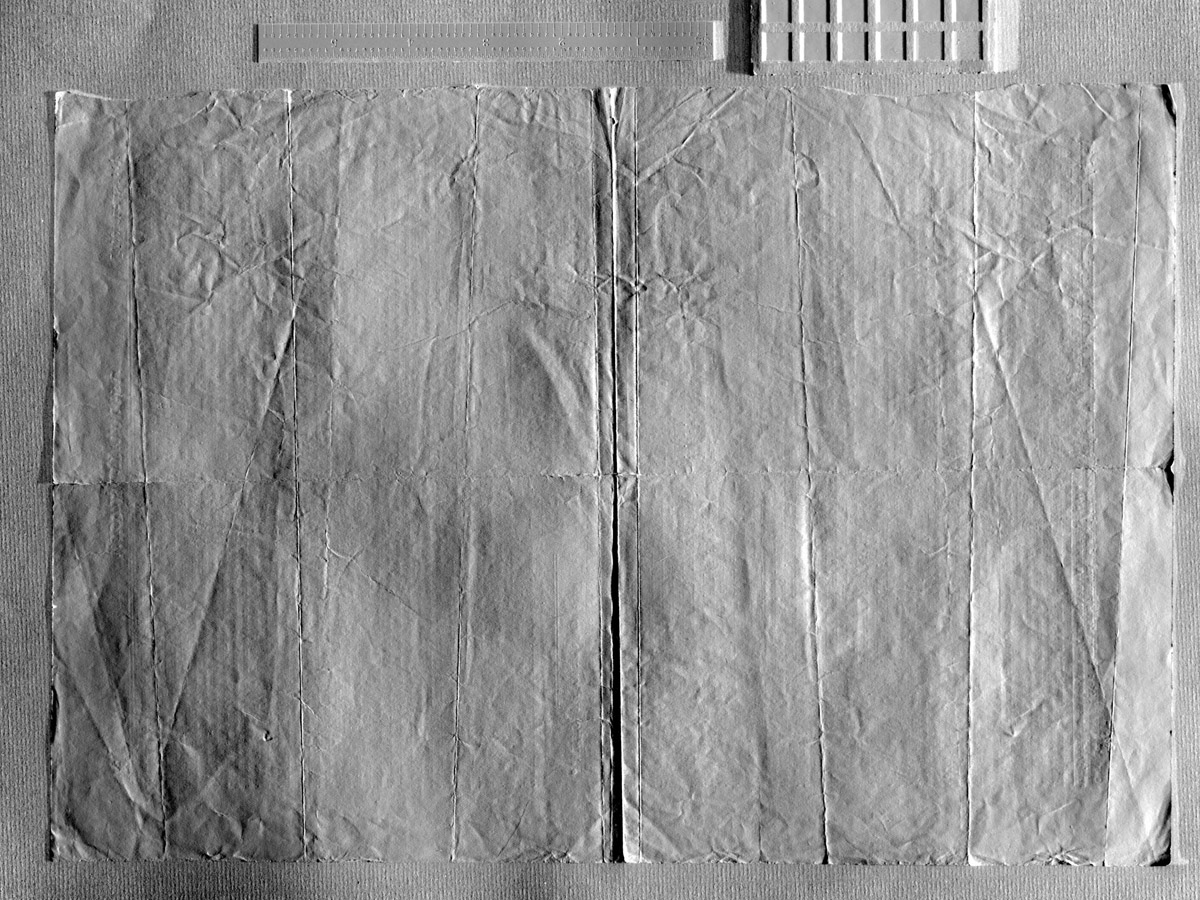

For example, our processed spectral images (especially raking, color_raking, and IC3) show that the leaves drawn from the Quarterly Review (Livingstone 1870b) and Stanley (Livingstone 1870e/1870f/1870i/1870j/1870k) are generally flat in a manner consistent with them being taken from a bound volume, while the Pall Mall Budget leaves (Livingstone 1871e) have a prominent central vertical fold that reflects the possibility of that periodical being folded in half for distribution.

![A spectral image of Samuel W. Baker's map of the Albert N'yanza [Lake Albert] that Livingstone used as one of the source texts for the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870h:[map] color_raking). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). A spectral image of Samuel W. Baker's map of the Albert N'yanza [Lake Albert] that Livingstone used as one of the source texts for the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870h:[map] color_raking). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/the-diary-across-hands-space-and-time-2/liv_000204_0002_color_raking-article.jpg)

A spectral image of Samuel W. Baker's map of the Albert N'yanza [Lake Albert] from the Journal of the Royal Geographical Society (Livingstone 1870h:[map] color_raking). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. This processed image, which combines a color image with a raking image, presents the page folds – including the prominent horizontal fold at the center of the map – relative to the printed text on the page.

Likewise, Baker’s map (Livingstone 1870h), which appeared in the Journal of the Royal Geographical Society, also has a prominent central horizontal fold and secondary horizontal and vertical folds that suggest that the map was folded down to a smaller size for inclusion in the Journal as were the many other surviving exemplars of this map (and other similar maps published by the Journal).

Conversely, the pieces from Gorbello[?] (Livingstone 1870c) and Birdwood (Livingstone 1871e) have a more singular nature. Presumably, the letter from Gorbello[?] would have been folded in order to be sent to Livingstone, but that is not a given and a lack of spectral images for this item prevents detailed study. That said, visual inspection of the natural light images reveals that there is at least one horizontal fold across the leaf’s central axis, where the letter would have been folded in half prior, presumably, to be sent to Livingstone.

The unusual character of the Birdwood item – a proof copy of a forthcoming article – offers even more limited grounds for baseline expectations, and, indeed, our processed spectral images show no pattern of folding that might be decisively ascribed individuals handling this source text before Livingstone.

▲Broad patterns and categories of manuscript folding. The presence of original folds in the leaves, however, does not cover all the cases of the manuscript folds visible in our processed spectral images. Although too numerous to describe individually, the manuscript’s folds readily fall into a handful of patterns:

1) extensive but fairly minor folding (1870b);

2) minor folding of page corners in a random fashion (1870e/1870f, 1870i:XXI-LV, 1870i:LX-LXI, 1870j:LXII-LXIX);

3) asymmetrical folding of pages that, in both natural light and processed spectral images, bear prominent traces of saturation (1870i:LV-LIX);

4) inconsistent vertical and diagonal folding (1870k:LXX-LXXV);

5a) consistent and clearly deliberate vertical and horizontal folding (1870h:XVII-XX);

5b) consistent and clearly deliberate vertical and horizontal folding (1871e:LXXXVIII-CI); and

6) inconsistent, but deliberate vertical folding coupled with asymmetrical and apparently random folding (1871a/1871b)

Study of these patterns in relation to the source texts and other evidence reveals that we might link each of the patterns to a single source text (Quarterly Review: pattern #1; Stanley: patterns #2, 3, and 4; Baker: pattern #5a; Pall Mall Budget: pattern #5b; and Birdwood: pattern #6), and also allows us to group the patterns into broader categories.

A processed spectral image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870i:LVII raking). Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The folding here follows no discernable pattern and may be due to saturation or other handling that occurred while the manuscript was in Livingstone's possession.

Some patterns are probably a direct result of Livingstone’s handling of the manuscript. For instance, the asymmetrical folding on pages with prominent saturation (pattern #3) points to a close relationship between the two phenomena and suggests that the event that caused the saturation – which occurred while Livingstone was still alive – also produced the folding (see The big stain).

Other patterns seem to follow on from Livingstone’s reconfiguration of the source texts to create the diary (see Creating the 1870 Field Diary), as in the case of the many minor folds and creases visible on the leaves of the first gathering (pattern #1), which are generally consistent with Livingstone (and others after him) slightly bending up the leaves while handling and flipping through the pages of this gathering.

Yet other patterns do not easily allow for any kind of categorical account. The deliberate folds at the center of diary pages written over the Birdwood leaves (pattern #6), to take one example, show that someone folded these leaves in half at some point (perhaps to keep them together?), but the available evidence prevents further assessment as to whether this folding (or, for that matter, the many other folds and creases visible at the edges of these pages) happened before the leaves came into Livingstone’s possession, while they were in his possession, or after his death.

A processed spectral image of three pages of the 1870 Field Diary that Livingstone wrote over a single page from the Pall Mall Budget (Livingstone 1870e:XCIX, C, CI raking). Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The principal folds here align with expectations for this source text and so were probably instituted by other individuals before the text reached Livingstone.

Finally, some patterns clearly align with expectations as to how the source texts might have initially been folded (see Original folds), and so it seems likely that others individuals instituted those folding patterns before the source texts reached Livingstone (patterns #2, #5a, #5b).

As a result, some questions about the folds in Livingstone’s manuscript must necessarily remain. However, the evidence available – especially as enhanced or revealed by our project – does enable us to offer a casual account of the majority of folds in the manuscript, to understand how these folds relate to the evolving functions of the manuscript (and its source texts) over time, and, ultimately, to weave the history of these folds into a larger chronology of events in the life of the 1870 Field Diary.

Page Impressions Top⤴

Our raking light spectral images also enable study of the impressions on Livingstone’s manuscript pages. In contrast to the folds, the impressions bear a much more subtle and varied character and so appear too extensive and diverse to characterize comprehensively. In fact, nearly every page of the 1870 Field Diary exhibits a variety of seemingly ad hoc impressions across its surface. There are two exceptions, however, which differ significantly from all other impressions made on the pages of the manuscript.

First, sequential review of the leaves of the second gathering shows that nearly every page in each of the following sequences – 1870e, 1870i/1870j/1870k/1871a/1871b, and perhaps others – bears a horizontal oval impression that roughly spans the extent of printed text on the page, top and bottom, left and right. On a handful of pages, additional heavier impressions appear on the edges of the oval, and these impressions roughly but imperfectly trace the contours of the oval.

A processed spectral image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870i:XXV raking). Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The topography on this page includes the oval impression that appears on a series of pages in this part of the diary.

The contours of the oval do not lend themselves to an obvious explanation. The oval may arise from general humidity, however subtle, in the central African environment and/or the interaction between this humidity and the printed ink on the page. Alternately, given that as Livingstone wrote on one page, he would have presumably kept the preceding pages in a stack, the oval may be the impression of some object that he used as a paper weight. However, such interpretations grow more from inference than evidence.

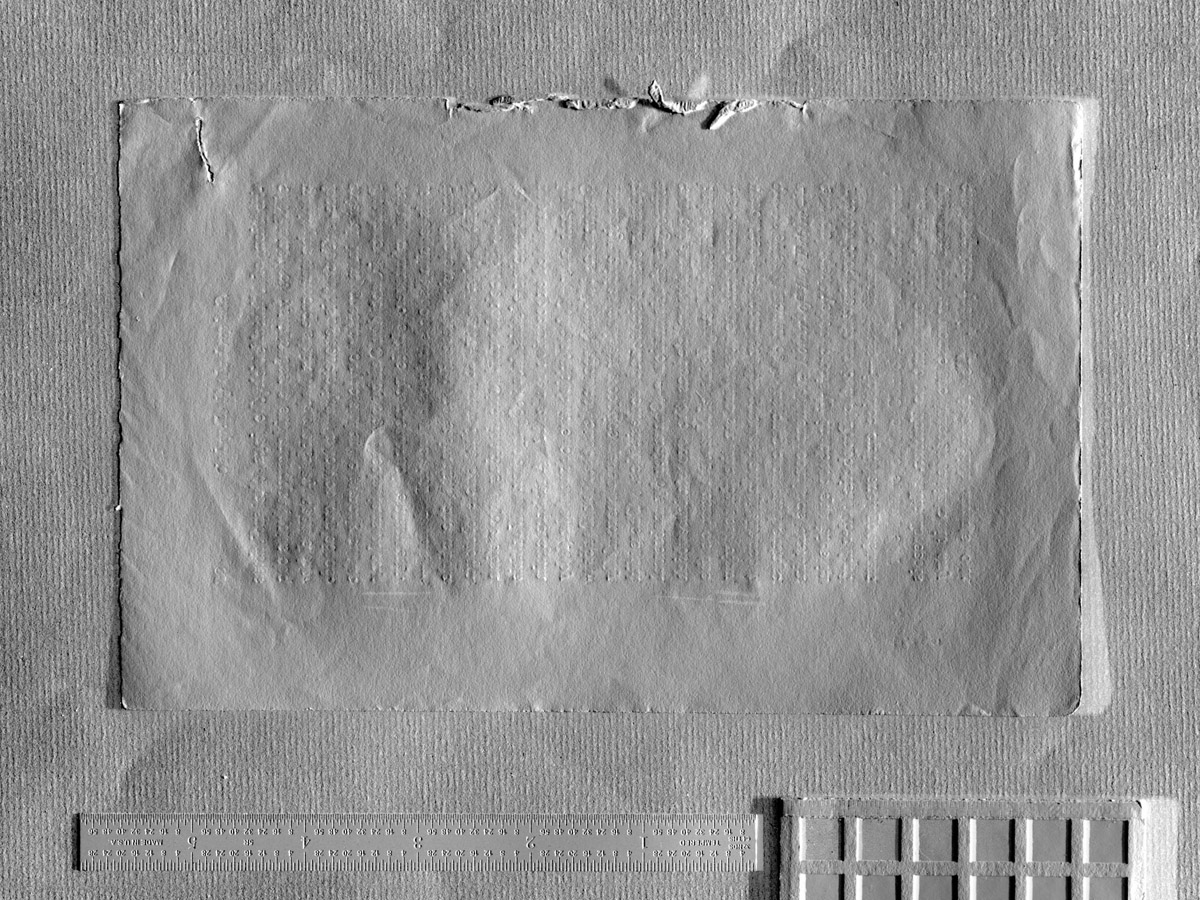

The oval may also hold some connection with the other, truly exceptional impression on the recto and verso of a single leaf of the source text (1870i:XXXV-XXXVI). This impression proves nearly impossible to study through first-hand examination of the original leaf at the National Library of Scotland, but our spectral images bring the impression out with striking clarity.

An image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870i:XXXV). Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The natural image of this page only hints at the complexity of the underlying topography through the semi-circular smearing of Livingstone's handwritten text.

In its basic character, the impression takes the form of a circle with a series of jagged lines radiating out from its circumference and, in some cases, running in rather deep channels to the edge of the leaf. The indentations visible on 1870i:XXXV suggest that the impression originated on this side of the leaf. The nature of the impression allows for a few significant characterizations, although definitive assessment must be elusive without additional evidence.

For instance, visual inspection of Livingstone’s handwritten text shows that it is smeared and that this smearing precisely follows the contours of the impression, a point that suggests that Livingstone’s writing pre-dates the impression.

-article-1200.jpg)

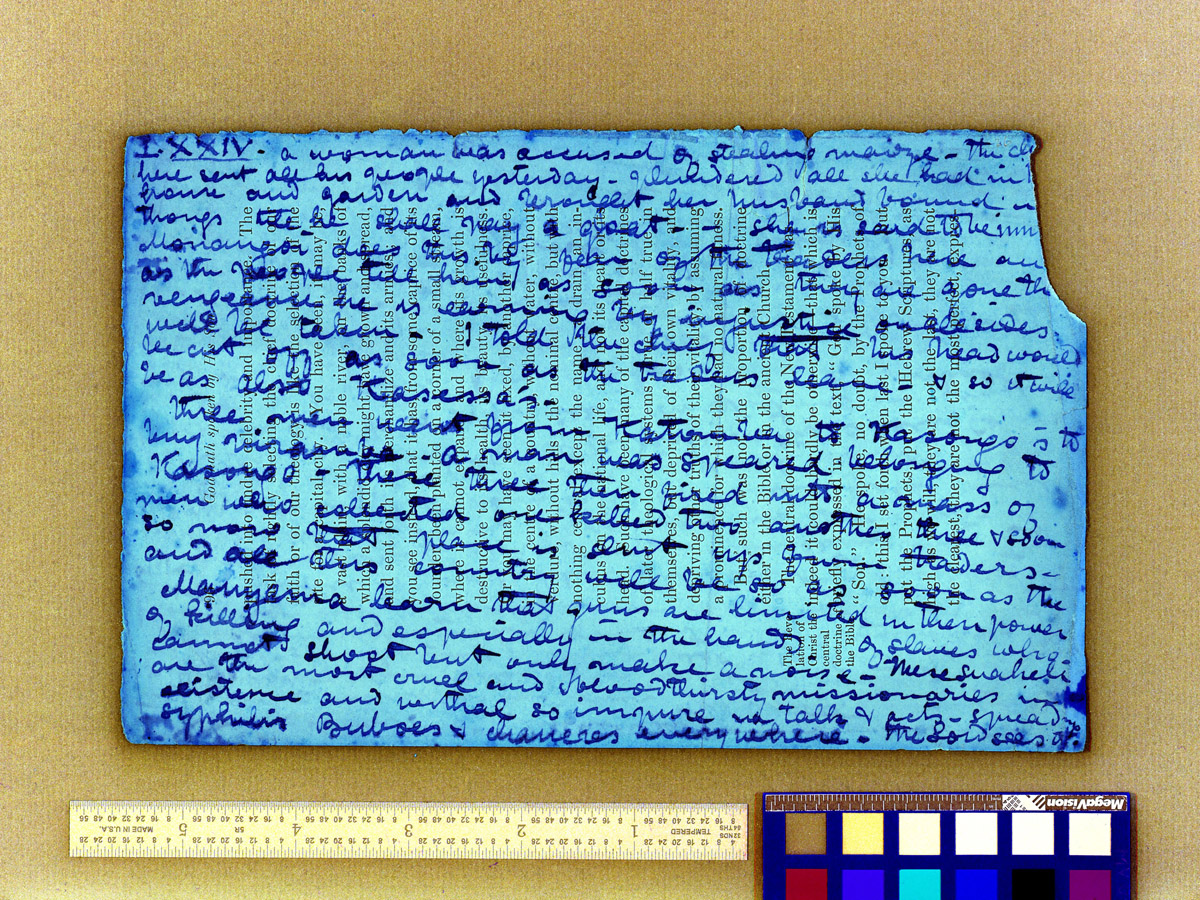

A spectral image of the same page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870i:XXXV ICA_pseudo_32). Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. This spectral image, processed to highlight staining, helps characterize the extent of the circular impression on the page.

Next, other than the smearing, neither our raking images nor any of our other processed spectral images indicate that there is any other sort of substance on the page in the vicinity of the impression consistent with its shape. In other words, it seems likely that the impression is due to liquid saturation and that that liquid was water.

Finally, given the shape and potential liquid substance, it seems quite likely that Livingstone or someone else placed a cup or other such container with water onto the page, and the water from this vessel saturated the page to produce the pattern we see today.

The location of the circle relative to the more subtle oval impression (i.e., in the center of the oval) – which our raking images show to be present even oc301ad6d-8a42-4467-854c-5ba54a7f63ad'

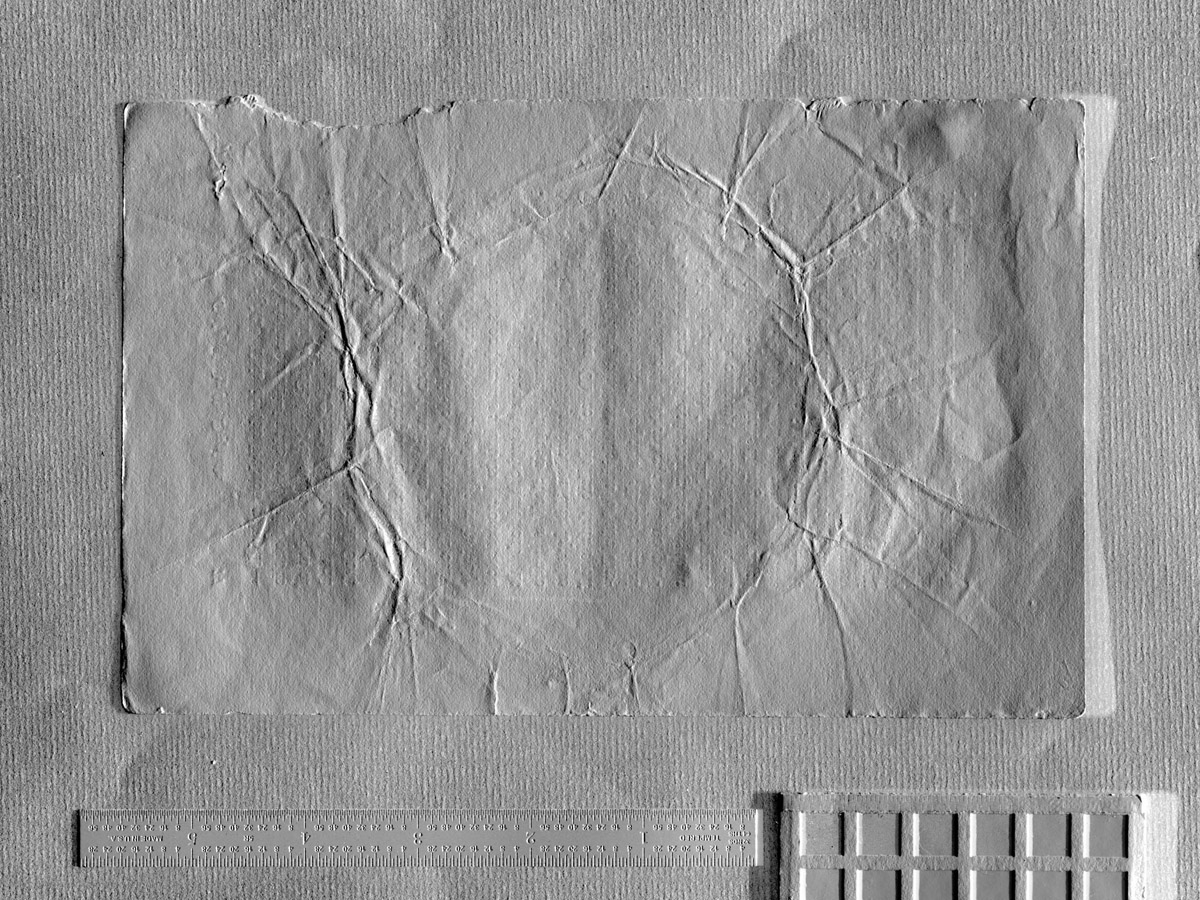

Another spectral image of that same page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870i:XXXV raking). Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The dramatic circular topography, visible in this image due to the use of raking lights, distinguishes this leaf from all the others that constitute the 1870 Field Diary.

However, this conclusion proves more speculative. As noted, the impression appears to begin on 1870i:XXXV and carries over to 1870i:XXXVI. If Livingstone were writing in sequence in the diary (not a given, of course, but a more likely scenario based on the evidence available in this part of the diary) and if the impression were made only after Livingstone wrote his text, then we would expect it to originate on 1870i:XXXVI, not 1870i:XXXV, as 1870i:XXXVI would have been the leaf facing up if Livingstone had just completed it, placed it on the stack of previous pages, and moved on the page 1870i:XXXVII.

Additionally, the impression, in its stark prominence, is limited to 1870i:XXXV and XXXVI, and there appears little if any trace of the impression in either the natural light or raking images of the pages either preceding or succeeding the leaf in question. This suggests that the impression was made on the leaf at a point when it was separated from the main stack of the diary pages, but point also takes our interpretation to the limits of what can be drawn from the evidence.

Torn Pages and Manuscript Holes Top⤴

Although nothing prevents first-hand study of the torn pages from and holes in Livingstone’s 1870 Field Diary manuscript in natural light, the variety of our spectral image renderings allows for a more detailed study of the characteristics of these features. The manuscript exhibits a variety of minor holes and tears, especially along the edges of the pages, but the majority of these appear to derive from regular handling of the pages and do not necessitate further comment.

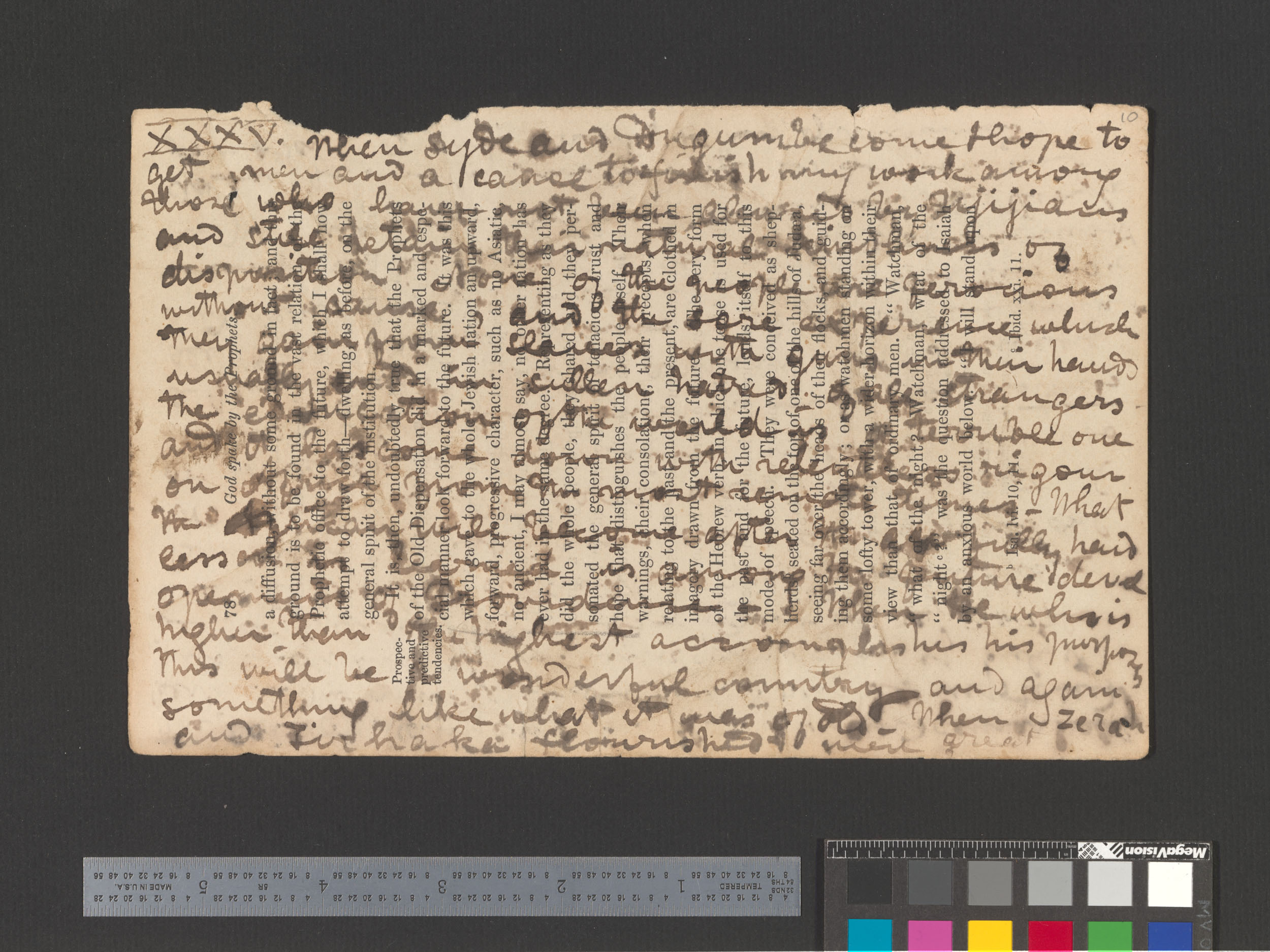

Images of two pages from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870e:XII; 1870i:XLV). Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The edges of the pages here are consistent with being torn out of the original book, Arthur Penrhyn Stanley’s The Bible: Its Form and Substance (1863), and pre-date Livingstone's composition of the 1870 Field Diary text since he clearly writes around the torn parts of the pages.

Likewise, the pages written over the leaves from Stanley’s book exhibit a few jagged edges clearly due to the leaves being ripped unevenly from the book (see, for instance, pages 1870e:XII/XIII, 1870i:XXV/XXVI-XXIX/XXX, and especially 1870i:XXXIII-XLVI). Given that Livingstone has written around such edges, they obviously pre-date his composition of the 1870 Field Diary. The cases cited below, therefore, fall outside of the above categories.

▲Torn pages. Only one set of pages, 1870k:LXXIV/LXXV, merits further discussion in this respect. These two pages, which occupy a single leaf from the Birdwood source text, have a larger portion of the page torn out on the right edge. This tear, which is generally straight except for when it curves towards the edge of the page center, has taken out the ends of a series of Livingstone’s handwritten lines.

As a result, in contrast to the cases just cited where such tears pre-date Livingstone’s composition and indeed he writes around them, the evidence here suggests that this tear post-dates Livingstone’s composition of his text.

A spectral image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870i:LXXIV spectral_ratio). Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. A portion of this page (upper right-hand corner) was torn off after Livingstone wrote his text as the missing segment clearly took a portion of Livingstone's writing with it.

▲Manuscript holes. Again, beyond the cases cited above, only two sets of holes in the manuscript pages require further discussion.

One of these sets has already received substantial review elsewhere (see Fourth sub-gathering), so those observations need not be revisited here, other than stating that the characteristics of this set of holes (1870i:XXI-LV) indicate that Livingstone used string or twine woven through the holes to hold together these leaves together.

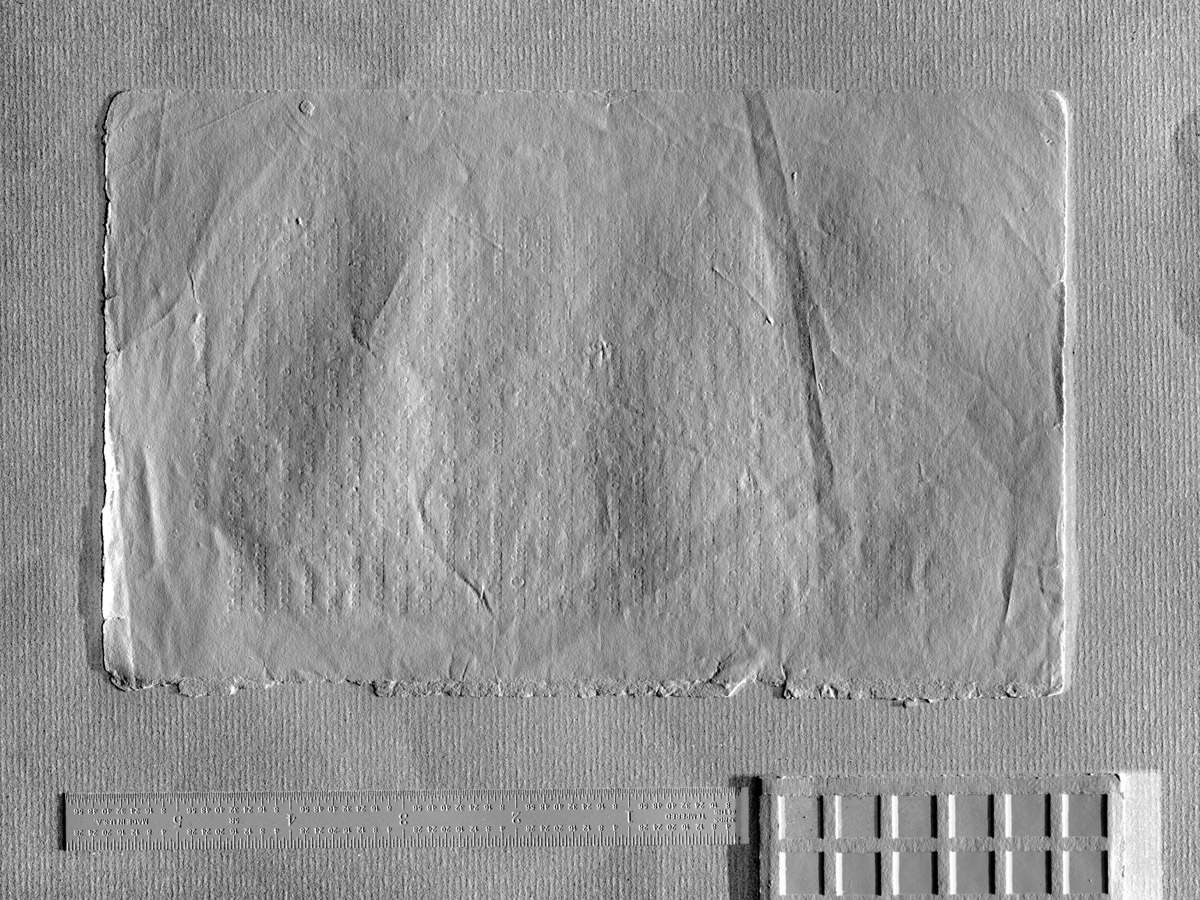

Indeed, we know from the first gathering of the 1870 Field Diary that Livingstone employed this practice on occasion because the leaves of the first gathering (1870b) remain bound to the present day, apparently with Livingstone’s original twine (visible in the images of 1870b:[70]).

![An image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870b:[70]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870b:[70]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/the-diary-across-hands-space-and-time-2/liv_000200_0070_color-article.jpg)

An image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870b:[70]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. Livingstone used twine looped through two small holes – both twine and holes are visible on the right-hand side of this image – to bind the pages of the first gathering of the 1870 Field Diary into a small booklet. For another picture of this twine, see Gatherings.

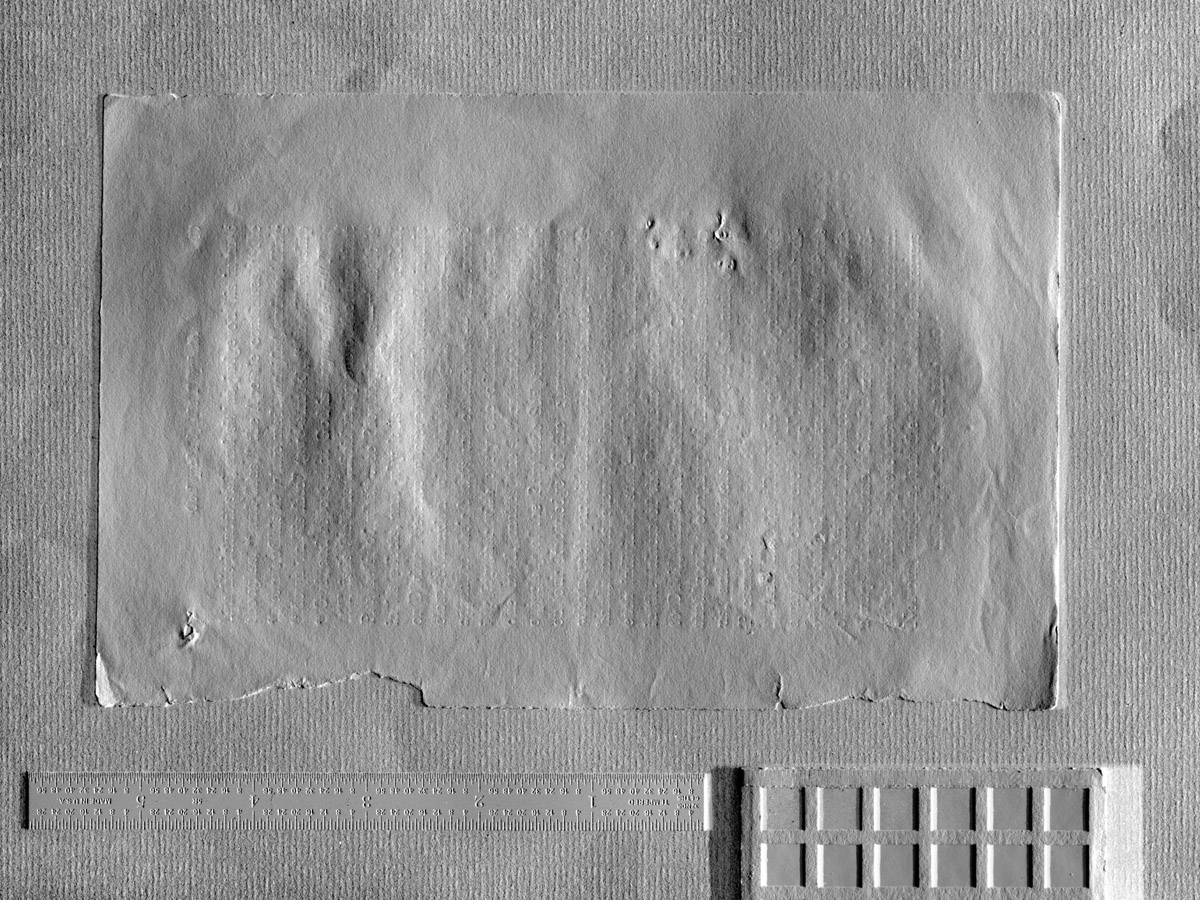

The other hole in the 1870 Field Diary manuscript represents another of the diary’s most interesting features. The hole originates on page 1870i:LV [v.2] where it has its broadest extent and is most prominent, then works its way backwards through the leaves of the diary, in an ever diminishing fashion, to page 1870i:XXXV – although there is no discernible relationship between this hole and the unique circular impression on 1870i:XXXV (see Page Impressions).

On page 1870i:LV [v.2], the hole takes the form of a small, diagonally-oriented oval and consists of a large opening around which portions of the page are bunched up; on page 1870i:XXXV, the hole is in fact no longer a hole, but a small cluster of faint impressions or indentations on the surface of the leaf. The pages between these two extremes present an ever evolving transitional character in terms of the hole.

![A spectral image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870i:LV [v.2] raking). Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). A spectral image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870i:LV [v.2] raking). Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/the-diary-across-hands-space-and-time-2/liv_000205_0036_color_raking-article-1200.jpg)

A spectral image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870i:LV [v.2] raking). Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. This processed image, which combines a color image and a raking image, highlights the extent of the damage done to the manuscript when a sharp object punctured this page and the sequence of pages preceding it.

The character of the hole indicates that some object punctured or pierced through a series of leaves, but stopped short of going all the way down. Whether the object was sharp or blunt is hard to tell because a blunt object could have done the trick if the pages were saturated enough.

Whatever the case, the event occurred after Livingstone had written his text because the hole takes out his writing on successive pages. Additionally, despite the coexistence of a significant stain on the majority of pages where the hole appears (see The big stain), our project team’s analysis of the two phenomena suggests that the piercing is separate from the stain.

A spectral image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870i:XLIV raking). Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. This page was one of the last to be impacted by the object that punctured this segment of the 1870 Field Diary (see above). As a result, although the manuscript hole becomes quite pronounced on the pages that follow, on this page topography the puncture registers only as a series of fairly minor impressions in the upper right-hand center of the page.

The origins of this puncture remain unknown, but certainly do not seem consistent with something that Livingstone – an otherwise meticulous and careful writer – would have done to his own manuscript deliberately.

There is no evidence that he attempted to compensate for this manuscript damage, as he did for smeared words in his manuscript by retracing them with Zingifure ink long after their original composition (see Reinking and Revision). From this, we think it is possible that this incident occurred after Livingstone’s death, when the manuscript and his body were being transported from the interior of Africa to the east coast by the porters who had travelled with him.

*

The topography of 1870 Field Diary offers another lens through which to understand the history of the manuscript. Elements such as folds, impression, torn pages, and manuscript holes reveal the diverse functions of the manuscript pages both before and after they became a part of the diary. The elements also show the close relationships between the materiality of the manuscript and Livingstone’s decisions in arranging and composing his text. The next part of this essay concludes this strand of our analysis by considering the impact of various environments on the pages of the diary.

![Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_013723_0001-new-carousel_0.jpg)

![Processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's "Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal" (Livingstone 1870a:[3] pseudo_v4_BY), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's "Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal" (Livingstone 1870a:[3] pseudo_v4_BY), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000211_0003_pseudoBY_940_by_592-carousel.jpg)

![David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, [1869], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland: CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, [1869], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland: CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_003006_0001-new-carousel_0.jpg)