Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary

![Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/grid_images/liv_013723_0001-new-tile_0.jpg)

Cite edition (MLA): Wisnicki, Adrian S., dir. Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. Updated ed. In Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. University of Maryland Libraries, 2017. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/75c25c6c-c491-4059-b446-3562d7518c95.

Cite page (MLA): Wisnicki, Adrian S. "Introduction to Edition." Debbie Harrison, ed. In Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. Adrian S. Wisnicki, dir. Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. University of Maryland Libraries, 2017. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/75c25c6c-c491-4059-b446-3562d7518c95.

This page – published in its original form on 1 November 2011 – introduces our multispectral critical edition of David Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. This diary chronicles the months leading up to Livingstone's famous meeting with Henry Morton Stanley and records Livingstone's first-hand impressions of a horrific slave trading massacre he witnessed in central Africa. Livingstone composed the diary when short on both paper and ink, so he improvised by writing over a copy of The Standard newspaper and other scraps while using an ink concocted out of clothing dye. The result is a diary that is today almost completely invisible to the naked eye. In 2011, the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project restored the full text of this diary and published it online. This edition updates and enhances our previous edition, while fully integrating all relevant primary and secondary materials into Livingstone Online.

Note: This edition was 1st Runner Up in the DH Awards 2012 for "Best professional resource for learning about or doing DH work."

|

Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (first edition) has been peer reviewed and approved by NINES. Review date: 2012 |

Introduction to the edition

The publication of Livingstone’s 1871 Field Diary reveals for the first time the original record of a remarkable and traumatic period in the life of David Livingstone, the celebrated British abolitionist, missionary, and explorer of Africa. The date of publication coincides almost exactly with the date Livingstone completed this diary in central Africa 140 years ago. The original, previously unpublished text of the diary has remained inaccessible until now, due to the fragility of the paper and the near-illegible script. Thanks to cutting-edge spectral imaging and processing technology, the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project now makes all the surviving pages of the diary available through this electronic edition.

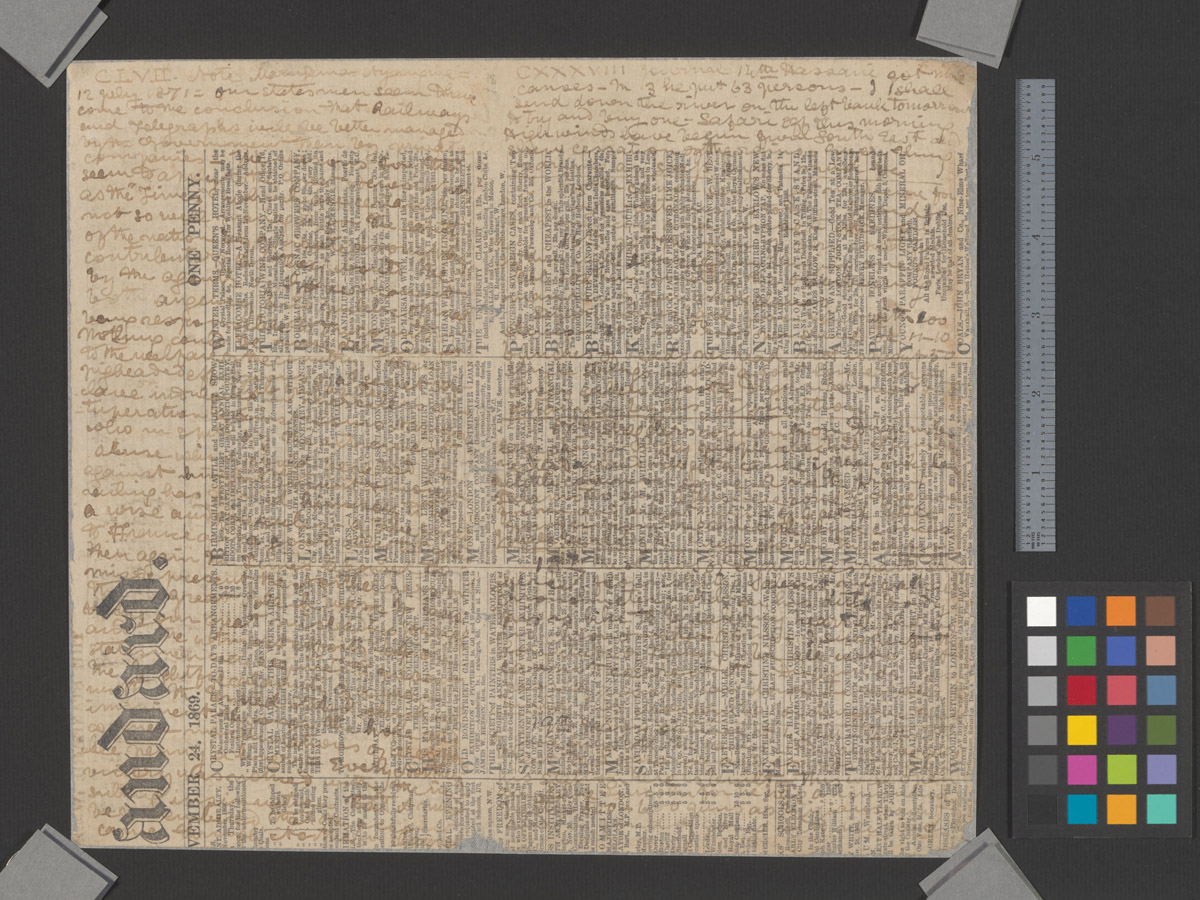

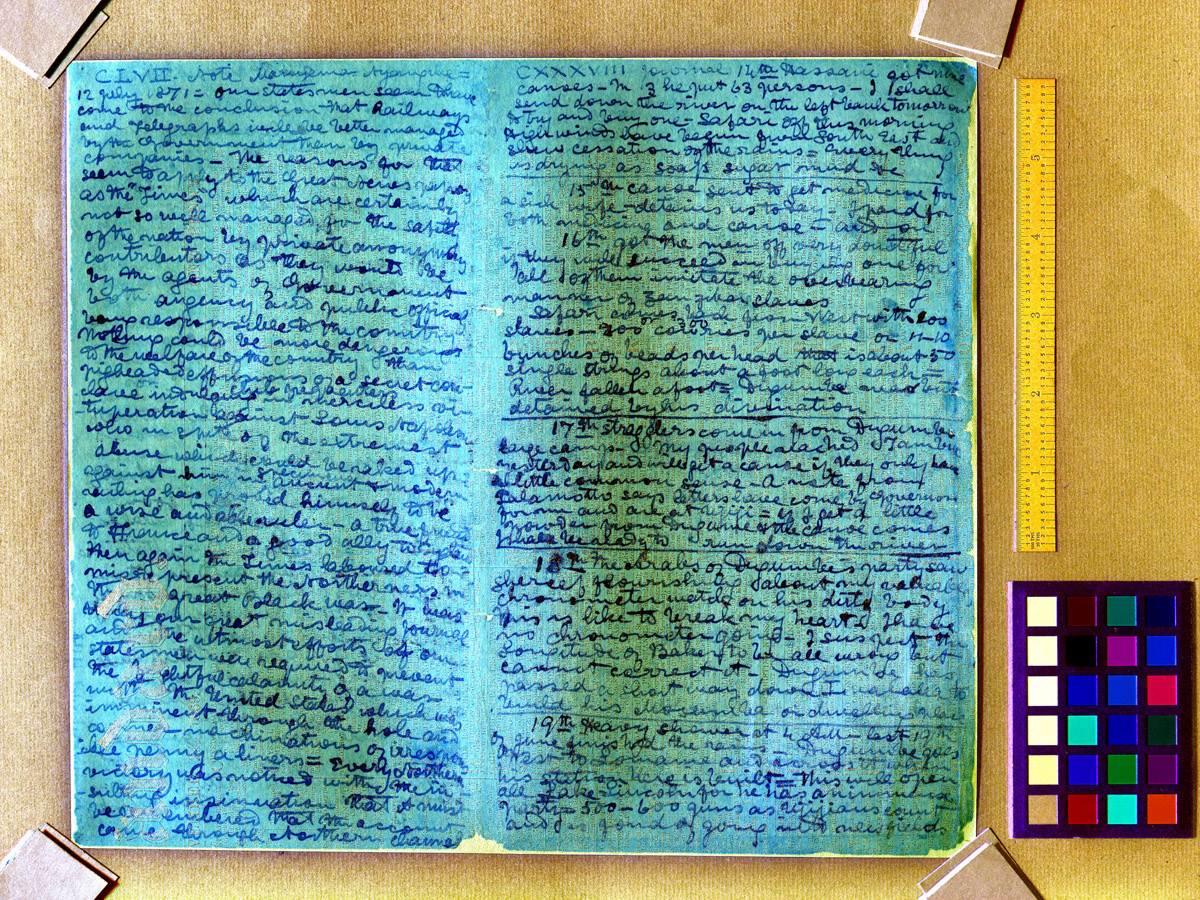

(Top) Natural light and (bottom) processed spectral images of two pages of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871f:CLVII-CXXXVIII color and spectral_ratio). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. These images demonstrate the dramatic ability of spectral image processing to reveal diary text that is otherwise nearly invisible to the naked eye. A portion of the printed newspaper title The Standard is visible at left.

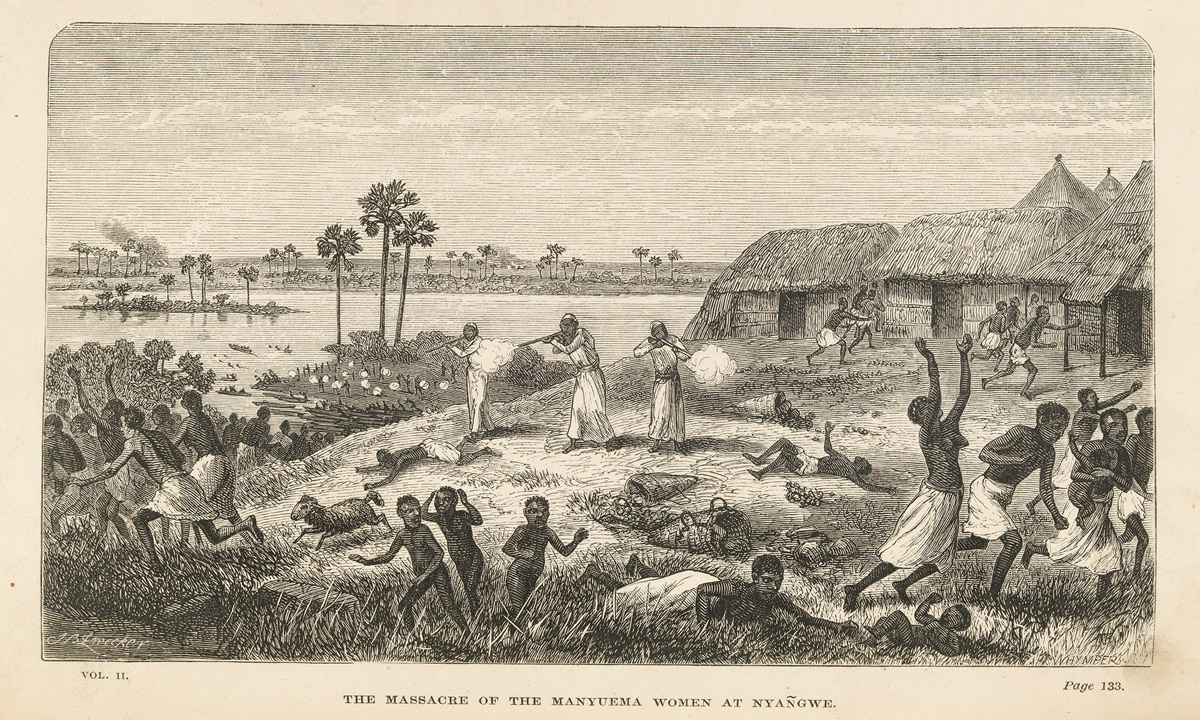

In 1871, David Livingstone spent five months stranded in a small village in the Congo called Nyangwe. He had run out of writing paper and had nearly run out of ink, so he improvised the materials for his diary by writing over an old copy of The Standard newspaper with ink made from the seeds of a local berry. On 15 July 1871, while still in Nyangwe, Livingstone witnessed a massacre of the local African population by Arab slave traders from Zanzibar. Some 400 or 500 Africans, the majority of them women, died in a single day – a scale of murder and death unprecedented in Livingstone’s experience.

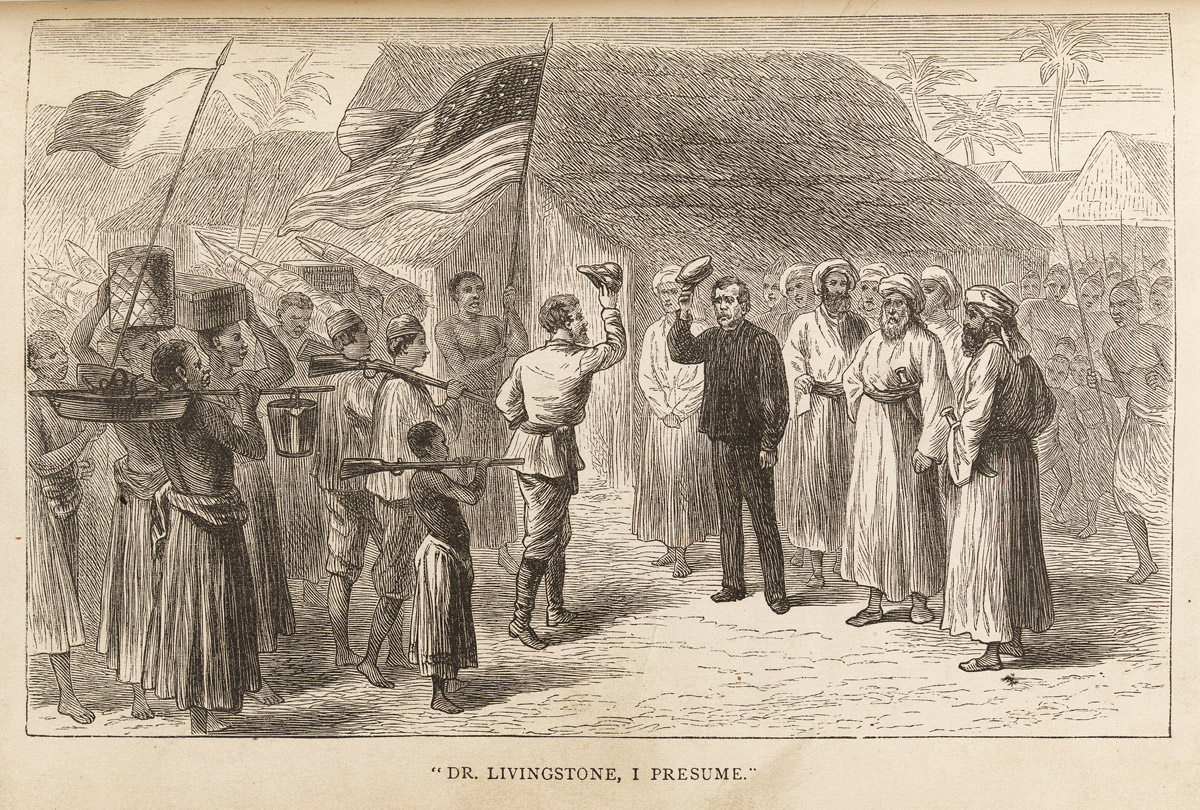

The massacre horrified Livingstone, leaving him too shattered to continue his mission to find the source of the Nile. He traveled 240 miles from Nyangwe – violently ill most of the way – back to Ujiji, an Arab settlement on the eastern shore of Lake Tanganyika. Here, Henry Morton Stanley, a reporter sent by The New York Herald to locate Livingstone (who had been "missing" for several years and presumed dead) found the Scottish explorer and purportedly greeted him with the iconic words, "Dr. Livingstone, I presume?"

Dr. Livingstone, I Presume? Illustration from Stanley's How I Found Livingstone (1872,2:opposite 412). Courtesy of Edinburgh University Library.

The rest is history. The meeting – one of the most famous encounters in the nineteenth century – and Stanley’s published accounts of Livingstone’s crusade against slavery secured the latter a prominent and enduring place in the public imagination. The meeting also launched Stanley’s own career as an explorer and led him, ultimately, to found the Congo Free State on behalf of Leopold II, the King of Belgium.

Yet despite its significance, Livingstone’s 1871 Field Diary – which chronicles both the months in Livingstone’s life leading up to the famous meeting and the Nyangwe massacre as it unfolds moment by moment before Livingstone’s eyes – has remained inaccessible to scholars and the public alike. The newspaper over which Livingstone wrote has deteriorated, and Livingstone’s improvised red ink has faded to the point of invisibility. From the time that the diary was returned to England after Livingstone’s death in Africa in 1873 to the present, it has not been possible to read and study Livingstone’s original words.

The Massacre of the Manyuema Women at Nyangwe. Illustration from the Last Journals (Livingstone 1874,2:opposite 133). Courtesy of Edinburgh University Library.

Today, the first phase of the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project – a unique transatlantic collaboration between scholars, scientists and educational and archival institutions – has completed its work on the diary. The complete original text is now made available worldwide as a free online resource. The diary, as those who read it will soon discover, offers an astonishing glimpse into Livingstone’s conflicted thoughts and actions during the most crucial period in his life. Instead of the saintly hero of Victorian mythology, the individual who emerges from the pages of the diary is passionate, vulnerable, and deeply torn about the violent events developing around him.

Bonus: Study the original first edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (external link)

Together with the text of the diary, the project team is delighted to make available an exciting and rich array of complementary materials:

- a collection of processed spectral images that digitally preserves all the pages of Livingstone’s 1870 and 1871 Field Diaries and includes full metadata, thereby allowing direct access to all the primary data on which this critical edition is based;

- a page that allows comparison between the original 1871 Field Diary, the highly revised 1872 version found in the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72), and the further revised version from the Last Journals (Livingstone 1874), the book posthumously produced by Livingstone’s friend, Horace Waller;

- critical, textual, and historical essays and notes; and

- a detailed project history that chronicles the fascinating journey of Livingstone’s words from the "rediscovery" of the faded diary in 2009 to its publication today as the first significant nineteenth-century British literary manuscript to be enhanced with spectral imaging and processing. The project history also provides download access to some 70 digital files produced in the course of the project that collectively provide an intimate and comprehensive look into the production of this critical edition.

The result – for the first time – is full access to a significant Scottish manuscript and the addition of an important primary resource to the study of African history and the history of the British Empire.

Adrian S. Wisnicki, Director

The Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project

1 November 2011, Edinburgh, Scotland

![Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_013723_0001-new-carousel_0.jpg)

![Processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's "Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal" (Livingstone 1870a:[3] pseudo_v4_BY), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's "Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal" (Livingstone 1870a:[3] pseudo_v4_BY), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000211_0003_pseudoBY_940_by_592-carousel.jpg)

![David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, [1869], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland: CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, [1869], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland: CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_003006_0001-new-carousel_0.jpg)