Project History (2)

Cite page (MLA): Wisnicki, Adrian S. "Project History (2)." Debbie Harrison, ed. In Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. Adrian S. Wisnicki, dir. Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. University of Maryland Libraries, 2017. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/73c6634d-9b48-417f-ae97-81cc19dc0f23.

This page, the second part of a two-part essay, sets out the history of our work to develop a multispectral critical edition of Livingstone’s 1871 Field Diary. The two-part essay provides an overview of all significant phases of project endeavor and for each phase describes all key project activities. (Note: Contemporaneous institutional affiliations for individuals have been retained although some of these have since changed.) Read the first part of the essay here.

Introduction Top⤴

This page, the second part of a two-part essay, sets out the history of our work to develop a multispectral critical edition of Livingstone’s 1871 Field Diary and complements the documentation related to the development of our critical edition. In doing so, the essay extends our efforts to conduct publicly-funded research in a transparent manner that promotes knowledge transfer and that opens all aspects of our research to critical review. Read the first part of the essay here.

Spectral Image Processing Top ⤴

The spectral imaging of the 1871 Field Diary and associated documents produced raw image sets of 202 Livingstone folia in total, not including extraneous image sets and sets of documents imaged for the NLS. 50 of these image sets (those of laminated folia) each contained 12 registered spectral image "digital negative" files (DNGs), while the remaining 152 image sets contained 16 DNGs due to the inclusion of "raking light" images. In other words, the spectral imaging of Livingstone’s diary resulted in the creation of 3,032 "raw" images files totalling, roughly, 750 GB of data. This data required processing by the team’s imaging scientists in order to make Livingstone’s handwritten text accessible to specialists and the public-at-large.

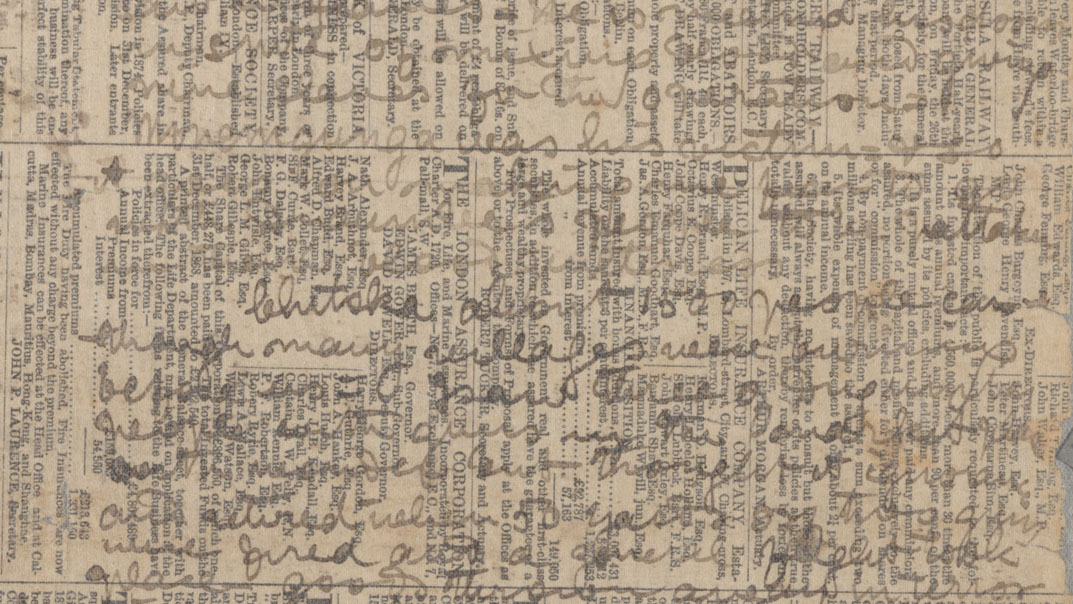

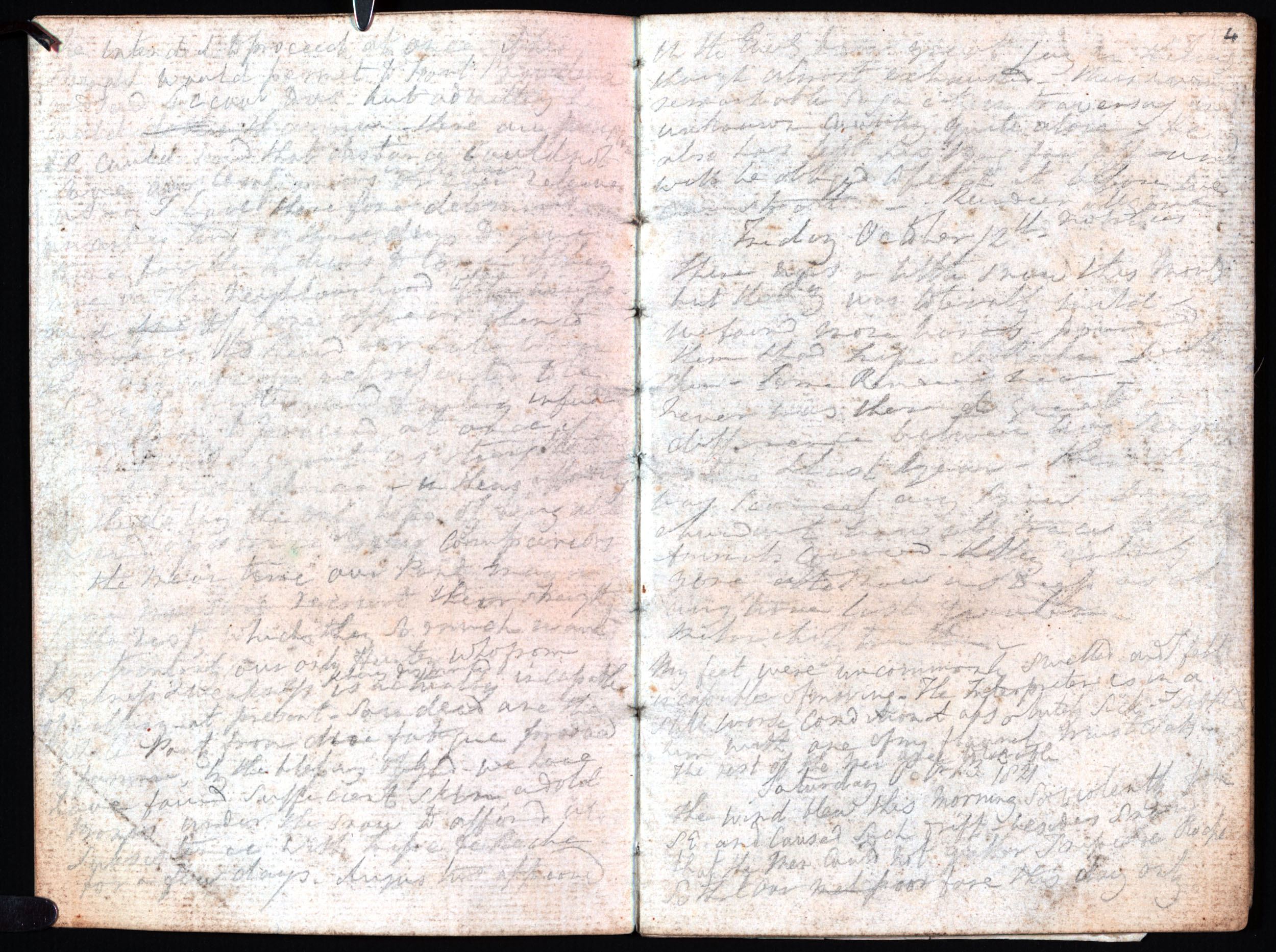

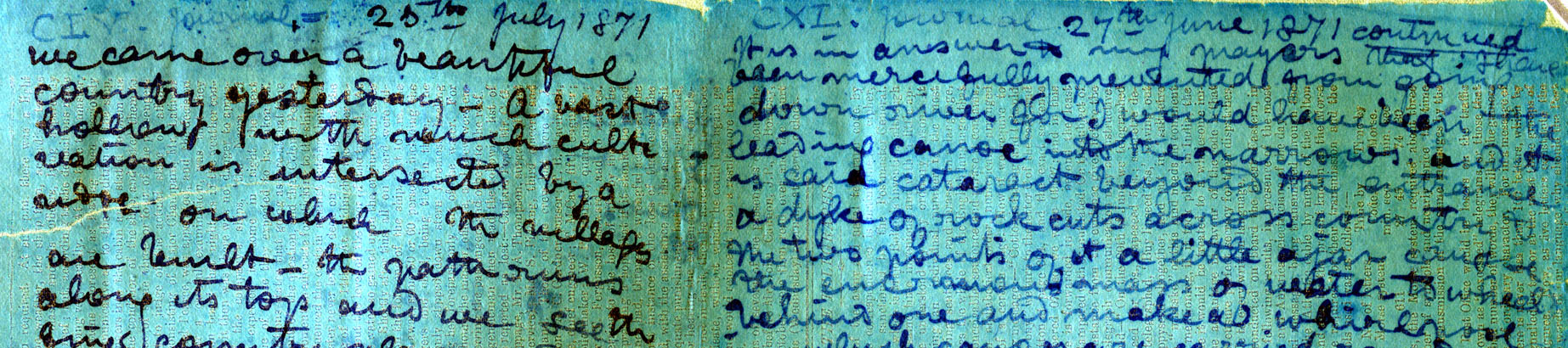

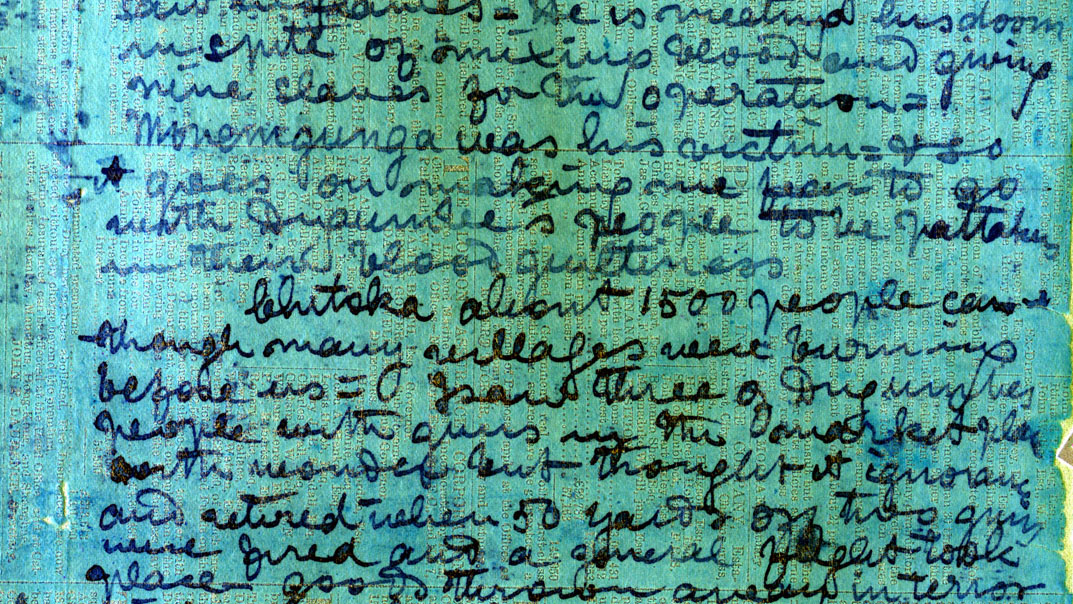

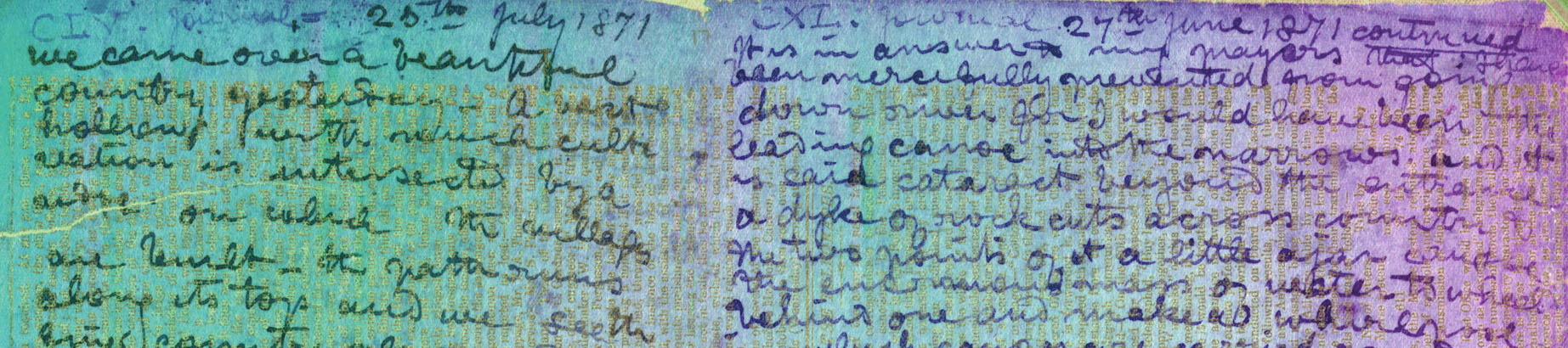

Natural light and three processed spectral images of two pages of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871f:CLV-CXL color and pcar721r, pca721r_multiply, and spectral_ratio), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. These images enable comparsion of the natural light image and a handful of processed spectral images.

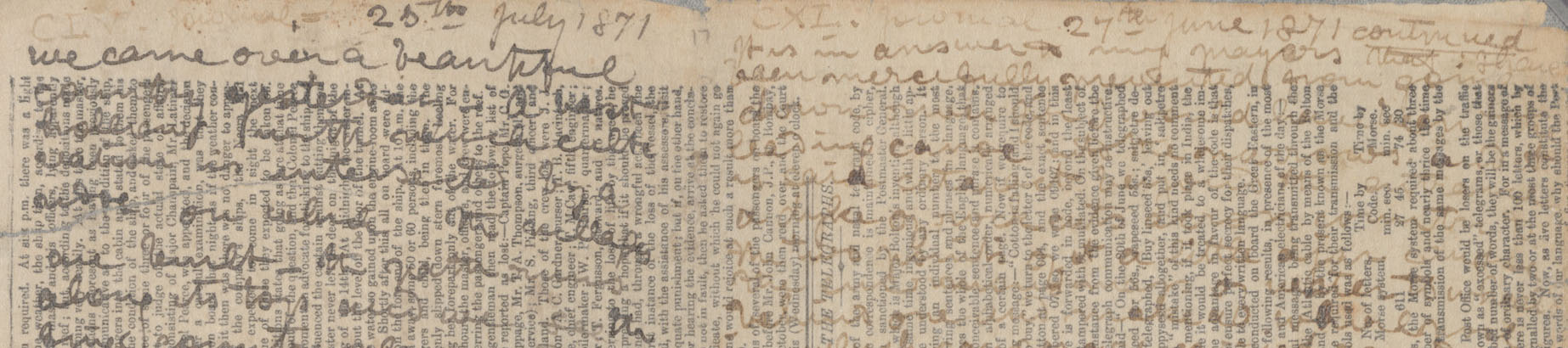

Spectral image processing uses tailored mathematical algorithms in order to manipulate and enhance raw spectral image data. In the case of Livingstone’s manuscripts, such processing relies on the fact that different ink types on a given page (for instance, Livingstone’s ink, the ink of the newsprint, etc.) behave differently under different bands of wavelengths of light. Imaging scientists use this differentiated behavior to create processed images (renderings of combinations of bands) that distinguish among what may be otherwise very subtle differences in color. The processing of the Livingstone data began while the team was still in Scotland in June 2010 and lasted well into the spring of 2011.

Learn more about spectral image processing in the related section from Livingstone’s Letter from Bambarre.

Download a set of curated Spectral Image Processing project documents

▲ Principal Component Analysis (PCA). Onsite processing in Scotland by EastonRoger L. Easton, Jr. (Rochester Institute of Technology). Imaging scientist for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. and Christens-BarryBill Christens-Barry (Equipoise Imaging, LLC). Imaging scientist for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. relied primarily on applying principal component analysis (PCA) to the raw image sets. In addition, Easton and his student Caroline HoustonCaroline Houston (Rochester Institute of Technology). Research assistant for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. continued to experiment with this technique after the initial imaging phase. The PCA technique uses combinations of an original set of images to construct an equivalent set of images ordered by statistical variance. The first principal component is a combination of the original images with the largest variance; the second principal component is the combination of the original with the next largest variance orthogonal to the first, etc. Images from initial PC bands ("high order" bands) correspond to the smallest data variances. If the images contain objects that differ in color, they may be distinguished ("segmented") in the set of principal components.

Roger L. Easton, Jr. and Carrie Houston while processing a spectrally imaged folio of the 1871 Field Diary in Rochester, New York, 2010-2011. Copyright Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project team. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported

Once the PC images are produced, the scientists examine the images to identify those that show different inks and insert these images into the red, green, and blue channels (RGB) of a "pseudocolor" (false color) image. If the handwritten ink appears as "light" in one of the PC images and "dark" in another, then the corresponding pixels may exhibit a color tone in the pseudocolor image that allows easier differentiation between the handwritten and printed texts. If necessary, the scientists further manipulate the pseudocolor image by using appropriate software to rotate the hue angle of the pseudocolor image to generate new combinations of the principal components. However, the process is not conducive to automation because of the manual steps involved and so is most feasible for the study of exceptionally illegible portions of text.

Download a set of curated Principal Component Analysis (PCA) project documents

▲ Spectral Ratio and Pseudocolor Rendering. KnoxKeith Knox. Imaging scientist for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary., who remained in Hawaii during the onsite imaging phase, supplemented both initial and follow-up PCA processing with techniques previously developed and/or refined for the Letter from Bambarre (also see Notes on Processed Spectral Images). In subsequent months, after the team and the data returned from Scotland, Knox also developed two additional techniques that proved instrumental to deciphering Livingstone’s writing.

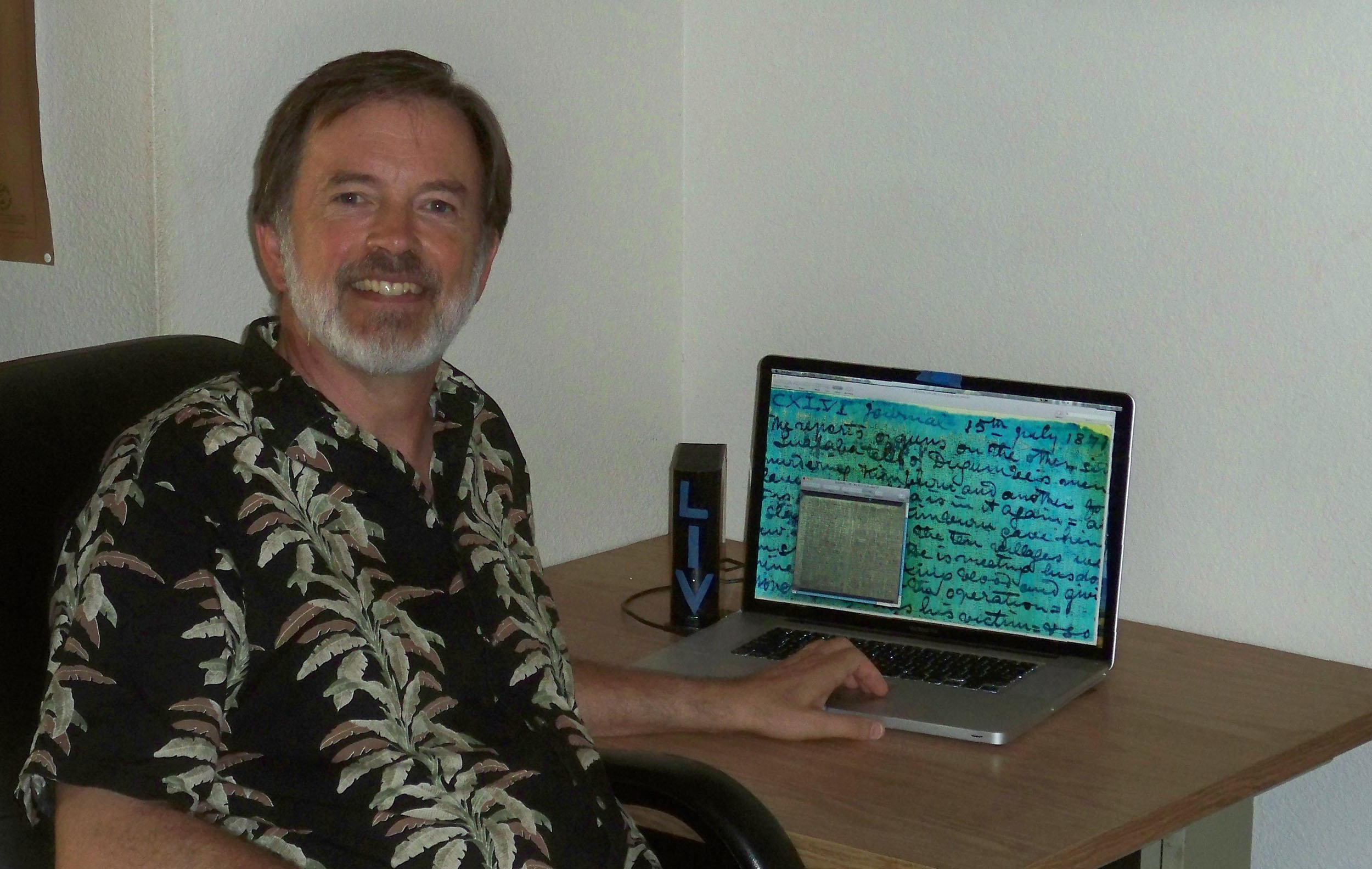

Keith Knox after a breakthrough in processing the spectral images the 1871 Field Diary in Maui, Hawaii, 2010. Copyright Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project team. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported

The first of these additional techniques lent itself to automation and so could be applied across all the Livingstone data sets without additional cost or labor. In December 2010, KnoxKeith Knox. Imaging scientist for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. discovered that although Livingstone’s writing faded as the wavelengths increased (and completely disappeared at the 940 nm wavelength), the printed text remained fairly constant across the spectrum. Knox therefore calculated the numerical ratio of the 450 nm, 592 nm, and 850 nm images relative to the 940 nm separation and put the resulting three images into, respectively, the red, green, and blue channels of a pseudocolor image. This technique effectively suppressed the printed text and made Livingstone’s handwriting very visible.

![A processed spectral image of a page of the Letter to John Kirk, 13 February 1871 (Livingstone 1871d:[2] pseudo_v3), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). A processed spectral image of a page of the Letter to John Kirk, 13 February 1871 (Livingstone 1871d:[2] pseudo_v3), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/project-history-2/liv_016111_0001.jpg)

A processed spectral image of a page of the Letter to John Kirk, 13 February 1871 (Livingstone 1871d:[2] pseudo_v3), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The spectral image processing here minimizes reverse-side ink bleedthrough.

A second technique, which could be partly automated, focused on minimizing ink bleedthrough. This technique involved rendering pseudocolor images using combinations of raw spectral images. In this case, KnoxKeith Knox. Imaging scientist for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. selected two images of the recto side of a given leaf (the 505 nm and 780 nm illuminations), and one image of the verso (505 nm) that he flipped horizontally. He performed a spatially local normalization of contrast and brightness on each image, then inserted these three images into, respectively, the red, green, and blue channels of a pseudocolor image. The resulting image displayed the recto text in cyan-blue and the verso text in green-yellow, a combination that significantly enhanced the legibility of the recto text.

Download a set of curated Spectral Ratio and Pseudocolor Rendering project documents

▲ Processing Objectives and Results. The Livingstone team developed a list of leaves for processing after the preliminary processing in June 2010, which established the viability of recovering Livingstone’s text. This list prioritized the most challenging images (those under the identifiers 297b and 297c [Livingstone 1871f]), while suggesting only color rendering for the most legible folia, the latter of which would be produced using a text file script with an executable program. The subsequent months of processing entailed a high degree of collaboration between imaging scientists and WisnickiAdrian S. Wisnicki (Indiana University of Pennsylvania). Director, lead scholar, and principal writer for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary., who assessed whether processing results met scholarly needs and who suggested further possibilities for experimentation.

Bill Chirstens-Barry and Roger L. Easton, Jr. process a spectrally imaged page the of the 1871 Field Diary at the National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, 2010. Copyright Callum Bennetts - Maverick Photo Agency. Used by permission.

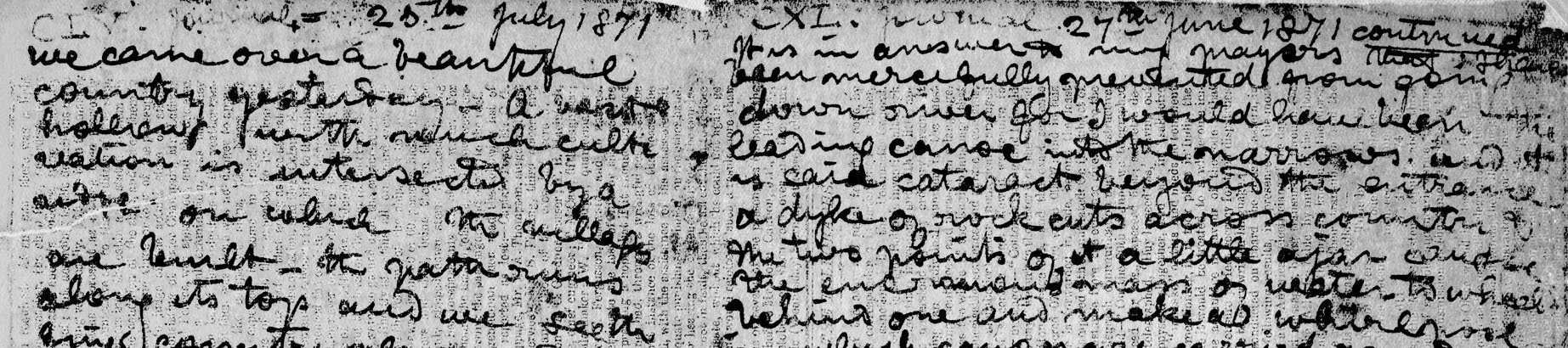

The scholar-scientist discussions also resulted in comparative analysis of processing techniques and the development of additional PCA and pseudocolor processing strategies, some of which could be automated. These additional techniques included a pseudocolor method that suppresses all written and printed text, and that highlights paper topography (raking). Furthermore, during this period, Christens-BarryBill Christens-Barry (Equipoise Imaging, LLC). Imaging scientist for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. developed the "Equipoise Toolbox" palette for ImageJ, an open-source image processing software package. This palette allowed WisnickiAdrian S. Wisnicki (Indiana University of Pennsylvania). Director, lead scholar, and principal writer for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. and other scholars to fine-tune the spectral images batch produced by the imaging scientists.

![A processed spectral image of two pages of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[8]-[1] raking). Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). A processed spectral image of two pages of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[8]-[1] raking). Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/project-history-2/liv_016114_0001.jpg)

(Top) Natural light and (bottom) processed spectral images of two pages of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[8]-[1] color and raking). Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The latter image reveals page topography that is invisible to the naked eye.

Ultimately, the work of the scientists resulted in the creation of a variety of spectral image processing techniques to recover the text of Livingstone’s 1871 Field Diary (see Notes on Processed Spectral Images for the full list). The imaging scientists applied nearly all of these techniques to the diary and, where possible, used automation to extend their work to the other Livingstone manuscript leaves captured in Scotland.

Download a set of curated Processing Results project documents

Data Management Top ⤴

Preliminary spectral imaging of Livingstone’s diary in Scotland and follow-up spectral image processing generated a significant amount of data and metadata. This data required far-sighted and detail-oriented data management to ensure efficient capture, production, and organization for long-term viability. The team’s data manager, Doug EmeryDoug Emery (Emery IT). Data manager for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary., directed this process from beginning to end with assistance from members of the Livingstone team.

Doug Emery and Roger L. Easton, Jr. review spectral image data of the 1871 Field Diary, 2010-2011. Copyright Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project team. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported

The team summarized data management objectives in their original NEH grant application: "The Nyangwe field diary project will provide a complete package of images with documentation and full metadata. The resulting archive data set will be based on the archive and metadata model used for the Archimedes Palimpsest. The product will be a completely self-documenting and autonomous data set. […] This will be a full digital archive of images that meets library and archival standards, as we have produced for previous projects."

Learn more about data management in the related section from Livingstone’s Letter from Bambarre.

▲ Preliminary Data Management. The team followed a series of intermediate steps to meet the data objectives, a process that spanned nearly the whole 18-month NEH and British Academy grant periods. The process began prior to imaging in Scotland with a series of discussions by email and teleconference in which the team set out the details of the data archive deliverable [now the Livingstone Spectral Image Collection], began to define XML transcription guidelines, and assessed metadata needs of key stakeholders. The team also explored the implications of various hosting and publication options.

Hard drives and other equipement needed for the spectral imaging of the 1871 Field Diary at the National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, 2010. Copyright Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project team. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported

During this period, EmeryDoug Emery (Emery IT). Data manager for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. began planning for the collection of appropriate metadata. He created a spreadsheet of the folia to be imaged that included location shelfmark (DLC or NLS), details of Livingstone’s handwritten "overtexts" and pre-printed "undertexts," and shots required (to identify folia to be imaged in segments). He reconfigured his online logging application to meet project needs and used the application to create Livingstone imaging projects and associated shot sequences. Finally, he instructed the imaging scientists in collecting image setup data.

From Baltimore, Emery continued to support daily metadata collection while the team imaged in Scotland – a heroic task given that it entailed waking up each day at 2:30 a.m. EST in order to be available for the team start time of 8:30 a.m. GMT!

▲ "Data Scrubbing." [Update note: The file naming scheme described in this section of the project history has since been replaced with a more standardized spectral image file naming scheme that corresponds to overall Livingstone Online file naming practices.]

Once imaging ended, the team moved to a lengthy period of data assessment and correction. In late July 2011, EmeryDoug Emery (Emery IT). Data manager for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. produced an initial evaluation of the Livingstone data, then based on this evaluation he, TothMichael B. Toth (R.B. Toth Associates). Program manager for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary., and WisnickiAdrian S. Wisnicki (Indiana University of Pennsylvania). Director, lead scholar, and principal writer for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. sought to refine the existing data management plan. In the coming months, Toth also outlined the overall path forward in a series of emails to the team, ultimately developing a phased approach based on prioritized goals, capability needs, and funding available for each phase.

The duration of the assessment and correction period had partly to do with the file-naming scheme created by the team. The scheme took the following form:

| Segment | Referent | Example |

| First | institution initials plus shelfmark | DLC297b |

| Second | Livingstone’s folio number(s) (in Arabic numerals) or, if not provided, begin with 001 (for both recto and verso), then 002 (recto and verso), etc. | 149-146 |

| Third | institution folio number or, if not provided, begin with 001 (for both recto and verso), then 002 (recto and verso), etc. plus "r" or "v" designation | 012r |

| Fourth | "0" if only one shot required; "0," "1," "2," etc. if folio imaged in parts | 0 |

| Fifth | shot sequence letter "A," "B," "C," etc. | A |

| Suffix | image or document type | dng |

This scheme produced a rather lengthy name for each image file, e.g., DLC297b_149-146_012r_0_A.dng. The advantage of the scheme lay in how much information it recorded. The disadvantage of the scheme, which the team realized only in hindsight, inhered in its complexity. The scheme allowed for a wide margin of error, especially as the hours and days in the darkened imaging room lengthened. Moreover, the need for preliminary processing during the imaging phase and beyond resulted in the exponential propagation of incorrect file names.

After EmeryDoug Emery (Emery IT). Data manager for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary.’s evaluation, KnoxKeith Knox. Imaging scientist for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. and WisnickiAdrian S. Wisnicki (Indiana University of Pennsylvania). Director, lead scholar, and principal writer for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. collaborated in reviewing and correcting the raw data and Knox’s processed data. Using Wisnicki’s list of file and folder corrections and additional input, Knox "scrubbed" the data in a series of steps:

- identify and correct duplicates, misnamed files, and excess files;

- create command files to convert the data according to Wisnicki’s list;

- produce PowerPoint summary of data set.

The process – which required many, many hours due to the complexity of the files names – lasted from August to December 2010, significantly longer than anticipated.

Download a set of curated "Data Scrubbing" project documents

▲ Creating the Data Archive. The need for extensive data correction pushed the spectral image processing phase to the spring of 2011. This development, in turn, delayed WisnickiAdrian S. Wisnicki (Indiana University of Pennsylvania). Director, lead scholar, and principal writer for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. and SimpsonKate Simpson (Edinburgh Napier University). Research assistant for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. from beginning XML transcription until late February 2011. As a result, the team continued to produce significant new primary data (images and transcriptions) well into June 2011 and so prevented final work on the archive [i.e., spectral image collection] until mid June.

In the NEH grant application, the team had described this next phase as follows: "After imaging and processing is completed, the imaging logs will be collated with other required metadata to generate complete metadata records for raw and processed images, and to assemble the final data archive." To realize these objectives, EmeryDoug Emery (Emery IT). Data manager for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. needed to complete a complex series of discrete tasks. These covered preparing the raw data, collecting the new data produced by the team, assembling and refining the database, collecting and building the metadata, and loading and packaging the data.

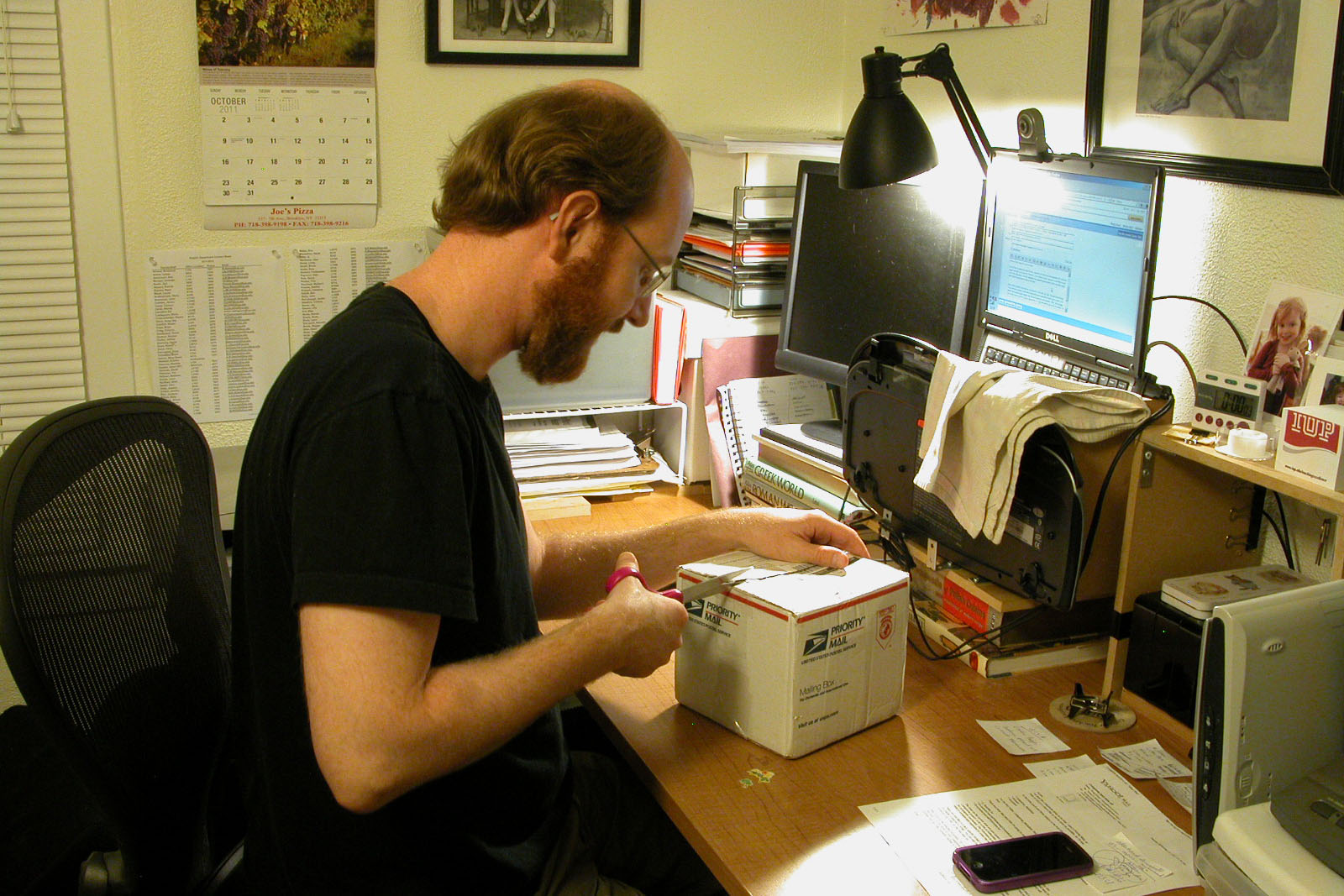

Adrian S. Wisnicki opens the package from Doug Emery containing the completed Livingstone spectral image data archive, Indiana, Pennsylvania, 2011. Copyright Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project team. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported

During the final months of the data management phase (June to Sept. 2011) EmeryDoug Emery (Emery IT). Data manager for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. worked in close collaboration with WisnickiAdrian S. Wisnicki (Indiana University of Pennsylvania). Director, lead scholar, and principal writer for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. and the imaging scientists to finalize the archive [spectral image collection], refine details of the archive structure, collect all required metadata, and identify missing processed images. In his efforts, Emery prioritized the 1871 Field Diary data but, where possible, included NLS data in bulk management tasks.

The Livingstone spectral image data archive as it copies onto Adrian S. Wisnicki's computer, Indiana, Pennsylvania, 2011. Copyright Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project team. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported

EmeryDoug Emery (Emery IT). Data manager for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. allocated much of his time to the labor intensive task of correcting the database so that it would work with the corrected file names produced by KnoxKeith Knox. Imaging scientist for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. and so that he, Emery, could produce accurate metadata. Emery also set up a server with the metadata database allowing WisnickiAdrian S. Wisnicki (Indiana University of Pennsylvania). Director, lead scholar, and principal writer for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. to verify the data and add new information as needed (including image rotation data). Finally, Emery and Wisnicki carefully corrected the names of processed files from Christens-BarryBill Christens-Barry (Equipoise Imaging, LLC). Imaging scientist for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary., EastonRoger L. Easton, Jr. (Rochester Institute of Technology). Imaging scientist for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary., and HoustonCaroline Houston (Rochester Institute of Technology). Research assistant for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary.. Emery completed the data archive [spectral image collection] on 27 September 2011, made a backup, then shipped the hard drive to Wisnicki, who received it 29 September, made a copy, and shipped it on to Stephen DavisonStephen Davison (UCLA Digital Library). Web developer for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. (Head of the UCLA Digital Library Program).

Bonus: Study the original first edition of Livingstone Spectral Image Archive (external link)

Double-bonus: Download the entire Livingstone Spectral Image Archive (except for archival images and MD5 checksum files) as a single ZIP file (588 MB). The archive includes full documentation, all supporting files, and all the website files that constitute the Archive itself as well as the first editions of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (UCLA Digital Library, 2011-13) and Letter from Bambarre (UCLA Digital Library, 2010-11). The missing archival images and MD5 files are now available in enhanced versions through our spectral image collection.

Download a set of curated Creating the Data Archive project documents

Restoring the Text Top ⤴

▲ Data Hosting. The size of the Livingstone data archive [spectral image collection] necessitated hosting by an institution that could provide robust, long-term data storage and curation. The NEH grant application stated that the archive would "be hosted by Livingstone Online, while backup data hosting [would] be facilitated by The Early Manuscripts Electronic Library."

To meet this requirement, WisnickiAdrian S. Wisnicki (Indiana University of Pennsylvania). Director, lead scholar, and principal writer for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. in collaboration with Michael Phelps (Executive Director of EMEL), Todd Grapone (Associate University Librarian for Digital Initiatives and Information Technology at UCLA), and Stephen DavisonStephen Davison (UCLA Digital Library). Web developer for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. (Head of the UCLA Digital Library Program) arranged for UCLA both to host the data and to seamlessly integrate it into Livingstone Online. Subsequent funding complications for Livingstone Online, however, necessitated that the integration be put off to a later date, and the team devised an alternative publication strategy: hosting by the UCLA Digital Library Program and joint publication by the Library and Livingstone Online. [Note: the updated 2017 edition of the 1871 Field Diary finally achieves the aim of integrating the edition into Livingstone Online. However, Livingstone Online and the updated edition are now hosted by the University of Maryland Libraries.]

▲ Creating a Publication Template / XML Encoding. In July 2010, the Livingstone team published the beta version of Letter from Bambarre through EMEL. This represented an interim solution necessitated by funding and resource constraints. The team transferred the Letter to the UCLA Digital Library once the partnership with UCLA had been established in August 2010. Kristin Jensen of Between the Lines Editing, Ireland, provided pro-bono editorial work, then WisnickiAdrian S. Wisnicki (Indiana University of Pennsylvania). Director, lead scholar, and principal writer for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. in collaboration with Sarina SinickSarina Sinick (UCLA Digital Library). Web developer for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary., a student at UCLA, began to refine and develop the electronic edition of the Letter. They completed the edition in May 2011 and formally republished the Letter, with announcements sent out to academic sites. To streamline efforts, the team decided to use the new edition of the Letter as the publication template for the 1871 Field Diary.

Kate Simpson positions a page of the 1871 Field Diary during the spectral imaging of the diary at the National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, 2010. Copyright Callum Bennetts - Maverick Photo Agency. Used by permission.

Simultaneously, WisnickiAdrian S. Wisnicki (Indiana University of Pennsylvania). Director, lead scholar, and principal writer for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. in collaboration with Kate SimpsonKate Simpson (Edinburgh Napier University). Research assistant for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary., a research assistant recruited from Edinburgh Napier University, began to transcribe and encode the 1871 Field Diary in XML. The transcription and encoding process got underway in February 2011 as the imaging scientists systematically began to produce the processed spectral images. Wisnicki’s prior XML experience was limited to encoding the exceptionally challenging Letter from Bambarre in TEI P4 using the original Livingstone Online tagging guidelines [no longer available online]. However, the Livingstone team decided to encode the diary in TEI P5.

As a result, Lisa McAulayLisa McAulay (UCLA Digital Library). Web developer for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary., the Librarian for Digital Collection Development at UCLA, now updated the Letter, created an encoding template for Wisnicki, and provided him with strategic encoding support. Later, James CummingsJames Cummings (University of Oxford). TEI advisor for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary., Manager of InfoDev (Research Support and Data Solutions) at the University of Oxford, also assisted the team in addressing the most difficult encoding issues. Thanks to this assistance, Wisnicki quickly developed TEI P5 proficiency and, in turn, trained Simpson who had no prior tagging experience. Wisnicki also summarized all encoding decisions in a detailed XML TEI P5 Encoding Practices document.

| (Left; top in mobile) Lisa McAulay during a break in supporting the TEI P5 coding of the 1871 Field Diary at UCLA Digital Library, 2011. (Right; bottom) James Cummings while tackling thorny XML coding issues related to the 1871 Field Diary at the University of Oxford, 2011. Copyright Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project team. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. |

The decision to encode each folio of Livingstone’s diary separately represented one of the Livingstone team’s most important encoding decisions. With some exceptions, each folio of Livingstone’s diary contains two diary pages, one on the left-hand side, one on the right-hand side. Adjacent pages are almost never continuous because Livingstone stacked, then folded the leaves of the diary to make two copy-books (now disassembled). As a result, the team chose to represent the physical artifact (the manuscript as it is) rather than the semantic artifact (what Livingstone "intended") in order to reflect the current state of the diary and to coordinate with the structure of the data archive, where the images for each folio would reside in a separate directory. [Note: the spectral image collection, which replaces the data archive in the present edition of Livingstone Online, now provides integrated access to XML-based transcriptions of all the folia of the 1871 Field Diary in a manner that reflects the features of the diary as both physical and semantic artifact.]

Download a set of curated Creating a Publication Template / XML Encoding project documents

▲ Transcription Outcomes. Livingstone’s words had taken an exceptionally long detour in their travels, but now had almost reached their destination. WisnickiAdrian S. Wisnicki (Indiana University of Pennsylvania). Director, lead scholar, and principal writer for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. and SimpsonKate Simpson (Edinburgh Napier University). Research assistant for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. completed the transcription and encoding of the diary in early August 2011. They succeeded in transcribing – and so making accessible – 99% of the diary’s original text for the first time since Livingstone wrote the document 140 years ago. Issues such as fading, blotting, bad handwriting, or missing pieces of the manuscript prevented the remaining 1% from being deciphered.

The majority of the issues fell outside the remit of the [first phase of the] Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project, which focused on using spectral image processing to separate Livingstone’s words from the printed texts over which he wrote. In other words, the team had a success rate of nearly 100%, an outcome that far exceeded even the most optimistic team predictions and that rendered unnecessary a number of alternative imaging and processing strategies outlined in the original NEH grant application.

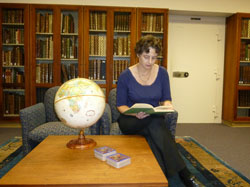

Heather F. Ball while reviewing a photocopy of Livingstone's Unyanyembe Journal (1866-72) in preparation for TEI P5 encoding in New York, New York, 2011. Copyright Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project team. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported

To complete the transcription and encoding process, WisnickiAdrian S. Wisnicki (Indiana University of Pennsylvania). Director, lead scholar, and principal writer for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. collaborated with research assistant Heather F. BallHeather F. Ball (Morgan Library and Museum). Research assistant for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. to produce an XML transcription of the corresponding portion of the Last Journals (Livingstone 1874). This transcription refined and corrected the rough transcription available from Project Gutenberg. Wisnicki, Ball, and A.J. SchmitzA.J. Schmitz (Indiana University of Pennsylvania). Research assistant for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. (Wisnicki’s graduate assistant from Indiana University of Pennsylvania) then corrected and revised the Last Journals transcription to produce an encoded version of the relevant portion of Livingstone’s handwritten Unyanyembe Journal (1866-72). Schmitz also used macros created for ImageJ by Christens-BarryBill Christens-Barry (Equipoise Imaging, LLC). Imaging scientist for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. to produce line-by-line mappings of the 1871 Field Diary.

Thanks to these final efforts, readers of the 1871 Field Diary would be able to study the original words of the diary alongside the revised 1872 Unyanyembe Journal version and the 1874 Last Journals published version. They would be able to survey firsthand the vast distance that separated the original and published versions of the diary and, as a result, trace the extent to which subsequent revisions by Livingstone, Waller, and others had transformed the original historical record. The mappings, when incorporated into the XML transcriptions, would also help support software tools to relate passages on the images to the transcriptions and vice versa [to date (2017), such software has not been implemented].

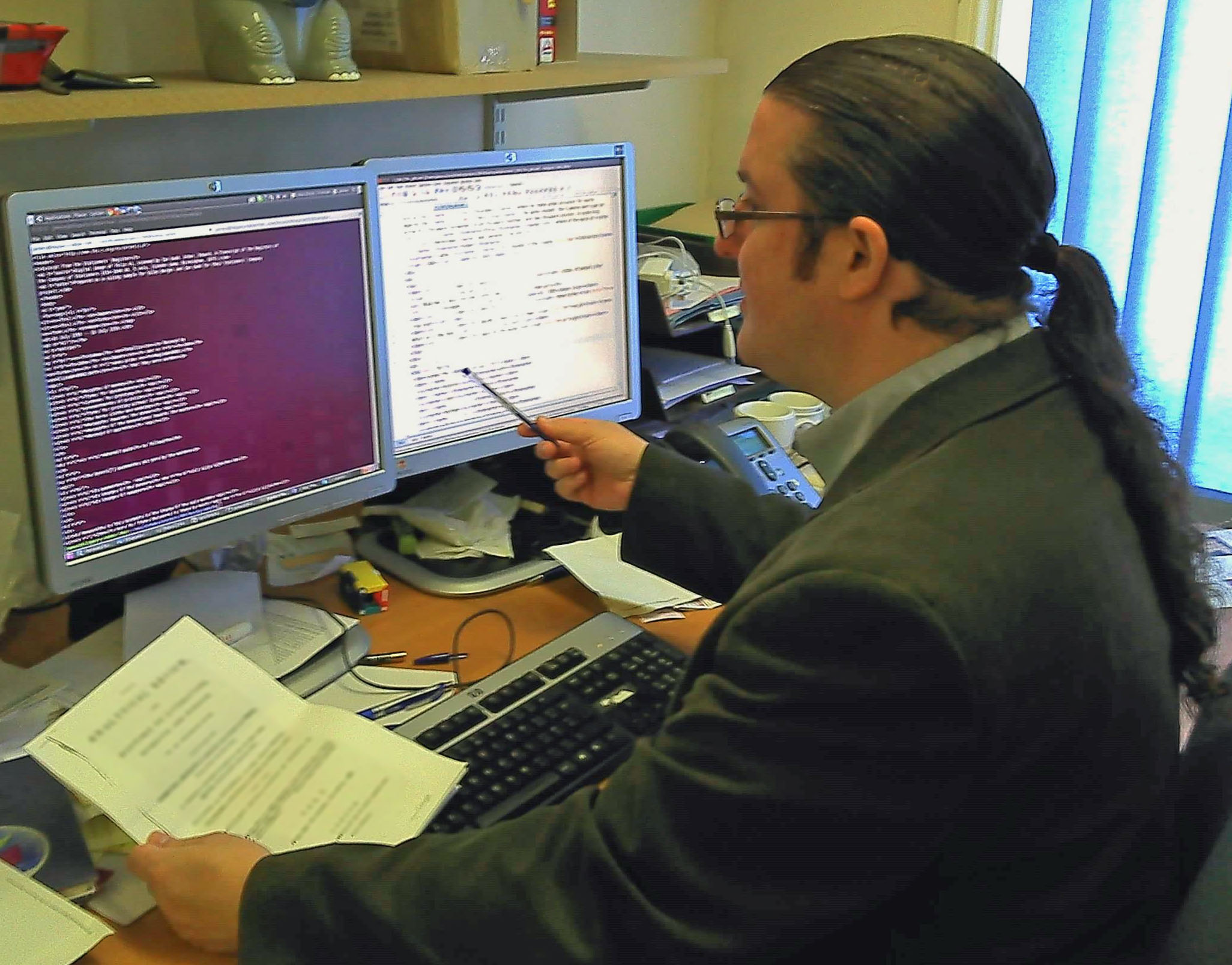

Adrian S. Wisnicki and A.J. Schmitz examine their TEI P5 encoding of Livingstone's Unyanyembe Journal (1866-72) at the Center for Digital Humanities and Culture, Indiana University of Pennsylvania, 2011. Copyright Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project team. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported

▲ The Electronic Edition. WisnickiAdrian S. Wisnicki (Indiana University of Pennsylvania). Director, lead scholar, and principal writer for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. collaborated with the staff of the UCLA Digital Library to develop the final format of the electronic edition [now updated to the present edition]. This format drew on the Letter from Bambarre template, and so used a similar layout and included many of the critical elements incorporated into the template. However, the team also decided to include a number of new features. Developing these features, however, proved quite challenging, and it was only by sheer force of will that the UCLA Digital Library staff finished the beta version of the site in collaboration with Wisnicki during the last month of the project (October 2011). Additional work on refining the site continued to the spring of 2012.

The UCLA Digital Library whiteboard created by Lisa McAulay in the last month of the first phase of the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project to divide up and allocate remaining website tasks, 2011. Copyright Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project team. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported

The team designed the new site features to showcase the scholarly and scientific accomplishments of the Livingstone team. The electronic edition also contains a selection of custom designed web pages:

Images and Transcriptions – Enables users to examine processed spectral ratio image versions of individual pages of the 1871 Field Diary alongside transcriptions. The embedded viewer allows users to view, rotate, otherwise manipulate, and download all processed spectral image versions of each page of the diary.

Color & Spectral Images [combined with the previous section in the present edition] – Allows users to view color and processed spectral images side by side.

Three Versions of the Text – Comparative page that enables users to study the three versions of Livingstone’s text (1871 Field Diary, 1872 Unyanyembe Journal, 1874 Last Journals).

Search Page [not available in the updated edition] – Enables users to search through and sort the full text of the 1871 Field Diary by keyword and significant XML-tagged content

Finally, the electronic edition includes a Project History & Archive section [the present Project History page plus the Project Documentation page], which offers a detailed and, at times, intimate look into the inner workings of the [first phase of the] Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project. Users can now not only overview the different stages by which the project evolved, but also download a representative selection of raw working documents produced in the course of the team’s efforts. As a result, the Project History & Archive section both catalogues the extent of people and resources required to undertake a significant spectral imaging and publication project and offers a roadmap for teams wishing to undertake similar projects in the future.

Bonus: Study the features enumerated above in the first edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (external link)

Download a set of curated The Electronic Edition project documents

Analysis to Dissemination Top ⤴

▲ Preliminary Data Analysis. The spectral imaging and transcription of Livingstone’s diary produced a treasure trove of data. Alongside many other tasks, WisnickiAdrian S. Wisnicki (Indiana University of Pennsylvania). Director, lead scholar, and principal writer for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. worked with team members to develop a preliminary analysis of this data during the final phase of the project. This endeavor embraced a number of discrete activities.

First, Wisnicki produced a detailed history of the diary that tracked the manuscript from the nineteenth century to the present day. Anne MartinAnne Martin (David Livingstone Centre). Institutional contact for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. (DLC) and Alison MetcalfeAlison Metcalfe (National Library of Scotland). Institutional contact for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. (NLS) supplied a number of crucial, internal documents to support the research. These documents coupled with materials previously assembled enabled Wisnicki to track – for the first time – the complex journey of the diary that ultimately resulted in the document becoming the first significant nineteenth-century British manuscript to be enhanced with multispectral image processing.

(Top) Natural light and processed spectral images of a page of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871f:CXLVI color and spectral_ratio), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The images show Livingstone's shift from Zingifure to iron gall ink in the middle of the page as he begins a new paragraph.

WisnickiAdrian S. Wisnicki (Indiana University of Pennsylvania). Director, lead scholar, and principal writer for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. also undertook a careful examination of Livingstone’s methods for composing and structuring the manuscript. This examination built on the XML encoding of the manuscript by Wisnicki and SimpsonKate Simpson (Edinburgh Napier University). Research assistant for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary., an endeavor that drew attention to a wide range of unique textual and material manuscript features. Wisnicki identified the practices Livingstone employed on a day-to-day basis in writing up his experiences and catalogued Livingstone’s strategies for organizing entries in the two copy-books that make up the key portion of the diary.

Most importantly, Wisnicki turned his attention to Livingstone’s inks. As far back as December 2009, Wisnicki had suggested to Gustavo Fermin (the assistant of Peter Beard, owner of the Letter from Bambarre) that Livingstone – in recoding the Nyangwe massacre – had, apparently, switched from the improvised ink he used to compose most of the 1871 field diary to what may have been his last supply of iron gall ink. This suggested that Livingstone had grasped the significance of the events unfolding before him and decided that it was worth drawing on his dwindling ink stock to produce a permanent record.

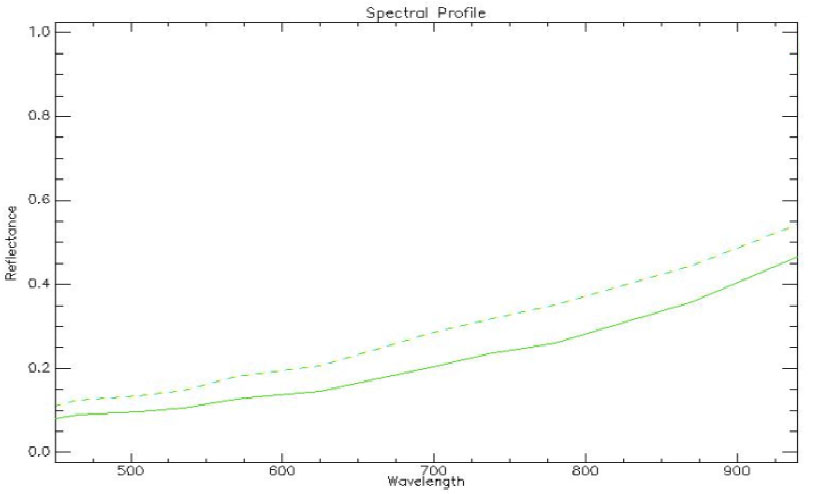

Spectral profile of a page of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871f:CXLVI). Copyright Roger L. Easton, Jr. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The dotted line represents the page's first paragraph, the solid line the second.

Fenella France (U.S. Library of Congress) advised WisnickiAdrian S. Wisnicki (Indiana University of Pennsylvania). Director, lead scholar, and principal writer for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. on the development of new techniques to identify and characterize inks and colorants, while EastonRoger L. Easton, Jr. (Rochester Institute of Technology). Imaging scientist for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. applied these techniques to generate the reflectance spectra for a sample of pages from the diary. The resulting graphs, which Easton collected in a series of PowerPoints, supported through scientific data what Wisnicki had previously deduced based on visual study of the processed images (especially the two paragraphs on page 297b/146).

During this phase, HarrisonDebbie Harrison (Birkbeck, University of London). Contributing editor and outreach director for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. carried out detailed comparative analysis of the 1871, 1872, and 1874 versions of the text. This work would become the basis of both future research and the press campaign (see below), while SimpsonKate Simpson (Edinburgh Napier University). Research assistant for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. heroically assisted Wisnicki in completing numerous tasks related to the diary’s critical apparatus. Wisnicki also carried out further analysis of the three texts to develop the Livingstone in 1871 section, which overviews some of the key new information revealed by the 1871 Field Diary. In addition, Simpson consulted with Ulrike Al-Khamis, a specialist in Arab/Islamic Art and Culture at the University of Edinburgh, and Paul Dundas, a Sanskrit specialist also at Edinburgh, to discuss a number of questions related to the Arab traders with whom Livingstone had travelled and to explore the issue of dating in Livingstone’s diary.

Download a set of curated Preliminary Data Analysis project documents

▲ Dissemination, Results Release, and the "UK Tour." The Livingstone team's dissemination strategy focused on both general and academic audiences. To reach academics, team members delivered a series of talks while the project was developing. These included conference presentations, lectures, and a "lightning round" presentation (two minutes, three images) on the project at the 2010 NEH Project Directors Meeting in Washington, D.C., on 28 September 2010. Alongside these presentations, the team also distributed an announcement to academic sites to mark the publication of the revised edition of the Letter from Bambarre in May 2011.

Adrian S. Wisnicki and A.J. Schmitz discuss promoting the publication of the 1871 Field Diary with Eric Meljac and Carly Dunn at Indiana University of Pennsylvania, 2011. Courtesy of Keith Boyer/Indiana University of Pennsylvania.

The initial publication of Letter in July 2010 had received international print and broadcast coverage, a development that underscored continuing global interest in Livingstone. As a result, HarrisonDebbie Harrison (Birkbeck, University of London). Contributing editor and outreach director for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. focused on both the project's academic and scientific dimensions in developing her press campaign for the publication of the 1871 Field Diary. She directed the team in drafting an appealing and dramatic press release with a strong public interest theme. She also sought to accommodate the complexity of the project and to acknowledge the broad range of collaborating individuals and institutions.

The promotional materials for the 1871 Field Diary included press releases aimed at the US and UK press, vivid project images, and briefing notes on key individuals, contributing institutions, and the scientific and literary dimensions of the project. This approach delivered a powerful story that focused on the human interest aspects of Livingstone's ordeals, while simultaneously providing sufficient biographical and technical information to satisfy the needs of the specialist press.

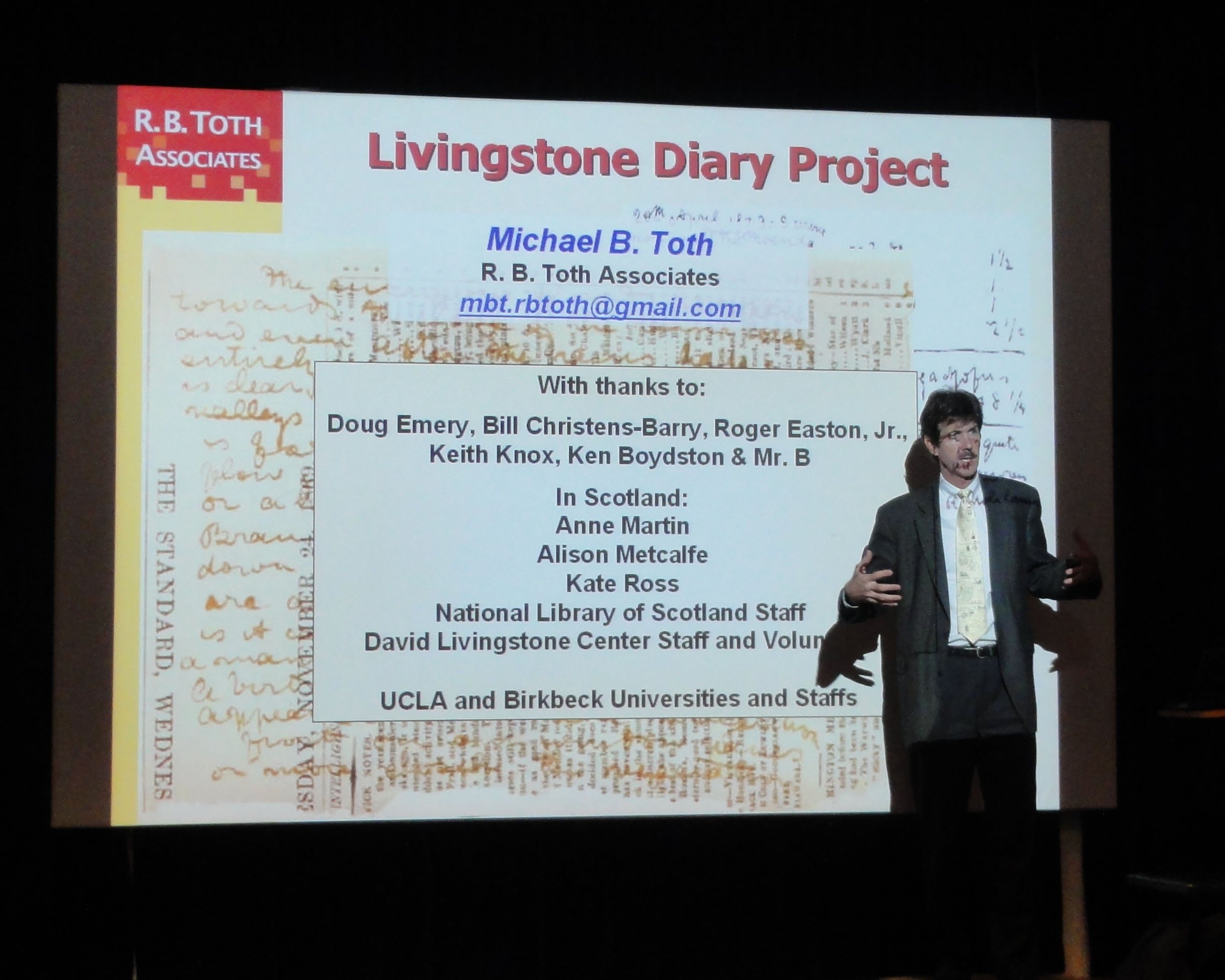

Michael B. Toth lectures at Birkbeck, University of London on the spectral imaging of the 1871 Field Diary, 2011. Published by permission of Jonas Fossli Gjerso.

The Livingstone team decided to release full project results in a "beta" edition on 1 November 2011, a propitious date given that it translated to 1/11/11 (US) or 11/1/11 (UK). More importantly, the date roughly coincided with the 140th anniversary of the Livingstone-Stanley meeting. Although Livingstone and Stanley offered divergent dates for their meeting (a point of continuing scholarly debate), the 1 November date represented a compromise between Livingstone's original date of 28 October 1871 (in the 1872 Unyanyembe Journal version) and Stanley's of 3 November 1871 (in a despatch to The New York Herald). While developing the beta edition, the Livingstone team also made plans to release a formal "first edition" of project results in the spring of 2012.

Keith Knox, Debbie Harrison, Russell Clearie (Provost of South Lanarkshire), Michael B. Toth, and Adrian S. Wisnicki at the David Livingstone Centre, 2011. Copyright National Trust for Scotland/ John Sinclair. Provost Clearie formally welcomed and introduced the team prior to their presentation at the David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre on 3 November 2011.

The team marked the beta release of project results with a British Academy-funded "UK tour" that included meetings with stakeholders and presentations at the National Library of Scotland on 1 November, the David Livingstone Centre on 3 November, the University of Oxford on 4 November, and Birkbeck, University of London on 5 November 2011. The team gave the presentations as panel lectures in which team members representing scholarship (WisnickiAdrian S. Wisnicki (Indiana University of Pennsylvania). Director, lead scholar, and principal writer for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary.), science (KnoxKeith Knox. Imaging scientist for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary.), technology and conservation (TothMichael B. Toth (R.B. Toth Associates). Program manager for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary.), outreach (HarrisonDebbie Harrison (Birkbeck, University of London). Contributing editor and outreach director for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary.), and postgraduate research (SimpsonKate Simpson (Edinburgh Napier University). Research assistant for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary.) described their roles on the project. These presentations solidified the project accomplishments for team members, stakeholders, and the public. By the last presentation, the team felt that they had decisively conveyed the significance of being the first people to restore and read Livingstone's diary since the nineteenth century.

Download a set of curated Dissemination, Results Release, and the "UK Tour" project documents

Lessons Learned / Future Projects Top ⤴

The Livingstone team carried out its work despite encountering a number of significant challenges. The team mitigated some of these challenges; other challenges delayed or compromised parts of the overall production schedule, but the team still delivered the final product within the NEH and British Academy grant periods. The principal challenges related to project funding, communication, and file naming.

▲ Challenge #1: Project Funding. The NEH grant brought the project to life and enabled it to accomplish its proposed goals of spectrally imaging and processing the manuscript of Livingstone’s diary. The team knew this project posed risks as proposed, especially with more complex tasks that might be uncompensated. The British Academy grant helped support the imaging effort in Scotland (June-July 2010) as well as a follow up visit (Oct.-Nov. 2011) to promote the project, share results with stakeholders, and receive feedback on the final product. However, the team proved unsuccessful in supplementing these funds during the NEH and British Academy grant periods to support additional work required. This outcome combined with an unflagging team ethic of delivering, as one member put it, "a BMW project on VW prices," resulted in every funded project member providing significant work for the project out of scope. Unfunded team members, in turn, uniformly assisted on a pro bono basis.

Members of the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project team (Ken Boydston, Kate Simpson, Alison Metcalfe, Roger L. Easton, Jr., Debbie Harrison, Michael B. Toth, Bill Christens-Barry, Adrian S. Wisnicki) at the National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, 2010. Copyright Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project team. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported

That said, everyone committed to the project or offered to contribute their time and talents – whatever the opportunity cost – foremost from a desire to support a worthwhile endeavor: the restoration of a key manuscript from a visionary explorer whose abolitionist ideals and progressive ideas on the intellectual capabilities of Africans often far surpassed those of his contemporaries. In retrospect, however, it became clear that the team should have developed the project in two, separately-funded phases, the first focusing on the creation of the data archive, the second on the critical edition of the diary. In particular, additional funding for the spectral image data capture phase would have allowed for a higher level of programmatic maturity, including better attention to data organization and data copying from the moment of capture.

▲ Challenge #2: Communication. The first phase of the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project brought together individuals residing across the UK and U.S., working in a variety of discrete fields, and affiliated with very diverse institutions. Team members and institutional representatives rarely met in person due to funding limitations, and most involved in the project spoke very different professional languages, a point that could create miscommunication despite the best intentions of everyone involved. Coordinating project phases and activities also proved challenging, especially given the limited time project personnel could devote to the project and the additional barrier of the Atlantic Ocean.

A common language: Members of the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project team (Ken Boydston, Bill Christens-Barry, Roger L. Easton, Jr., Kate Simpson, Michael B. Toth, Alison Metcalfe, Adrian S. Wisnicki, Debbie Harrison) celebrate the end of the spectral imaging of the 1870 and 1871 Field Diaries, Edinburgh, 2010. Copyright Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project team. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported

Preliminary imaging in Scotland did build strong relationships among and between team members and institutional stakeholders, and, furthermore, the Livingstone team used communications technology (email, teleconferences, Skype, file-sharing sites) to maintain these relationships and to draw on expertise available through the project team. However, a number of problems encountered during the spectral imaging phase in Scotland, including a large project footprint, might have been mitigated by a more comprehensive site survey. Additionally, regularly scheduled teleconferences as well as shorter briefings focused on bridging disciplinary divides might have enhanced communication among team members during all stages of the project.

▲ Challenge #3: File Naming. Initially, the team planned to deliver the final products (the data archive and the critical edition of the diary) to coincide with the 140th anniversary of the Nyangwe Massacre on 15 July 2011. However, a series of production delays associated with new image processing and data management challenges prevented the team from working to schedule. Processing carbon inks on paper with different spectral responses required additional experimentation and development of refined techniques from those used previously on palimpsests. Data management challenges all led back to the complexity built into the spectral image file naming scheme devised by the team (see "Data Scrubbing"). Fortunately, the 140th anniversary of the Livingstone-Stanley meeting offered a viable alternative publication date – first, because the anniversary also fell within the NEH and British Academy grant periods, and, second, because the 1871 Field Diary leads up to that meeting and even contains evidence that may help scholars determine the date of the meeting. That said, the team could have avoided these delays. The need to have simple spectral image file names represents one of the major lessons learned of the project. [Update note: This lesson did eventually lead to the implementation of simplified file naming practices for the Livingstone Online project as a whole.]

▲ Future Projects The Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project laid the groundwork for a number of future collaborative projects, as follows:

-

The project established solid working relationships among the scholarly and scientific team members, and between the team and institutional representatives from the David Livingstone Centre and the National Library of Scotland. These relationships represent the basis for future projects on Livingstone, especially as both institutions boast major holdings related to the explorer. [Update note: The relationships established by the 1871 Field Diary with these two institutions in fact became the basis of the subsequent Livingstone Online Enrichment and Access Project (LEAP, 2013-17) and a multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1870 Field Diary (2013-17; see next bullet point).]

-

The team has already collected the raw spectral data needed to support projects on Livingstone’s 1870 Field Diary (a.k.a. the Bambarre Field Diary) and select letters from the 1871 as well as Sir John Franklin’s 1821 Field Diary (see Imaging Schedule and Objectives). [Update note: Livingstone Online published the beta edition of Livingstone's 1870 Field Diary in late 2016; the raw spectral images of Franklin's 1821 Field Diary have not to date (2017) been published.]

-

Finally, HarrisonDebbie Harrison (Birkbeck, University of London). Contributing editor and outreach director for the multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. has created an innovative outreach program for British schoolchildren based on the project to be piloted in collaboration with the David Livingstone Centre. [Update note: This outreach scheme became the basis of the Livingstone Online outreach program created by LEAP.]

(Top) Natural light and (bottom) processed PCA spectral images of two pages of Sir John Franklin's 1821 Field Diary (National Library of Scotland, MS. 42237). Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. These images show the potential for spectral imaging to enhance Franklin's handwritten text.

These initiatives – which offer a number of possibilities for the team to continue its transatlantic, scholarly-scientific-institutional collaborations – promise to help to realize one of the overarching objectives of the spectral imaging team’s original NEH grant, the "Digital Humanities Start-Up Grant" (emphasis added).

![Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_013723_0001-new-carousel_0.jpg)

![Processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's "Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal" (Livingstone 1870a:[3] pseudo_v4_BY), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's "Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal" (Livingstone 1870a:[3] pseudo_v4_BY), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000211_0003_pseudoBY_940_by_592-carousel.jpg)

![David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, [1869], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland: CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, [1869], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland: CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_003006_0001-new-carousel_0.jpg)

![An image of two pages of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[8]-[1]), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of two pages of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[8]-[1]), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/project-history-2/liv_016113_0001.jpg)