The Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project: An Introduction

Cite page (MLA): "The Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project: An Introduction." Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. University of Maryland Libraries, 2018. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/8082ba50-e1cb-47bb-b5b8-18c9d2aeb395.

This section introduces the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project citing both its historical contexts and the groundbreaking modern technology that has made the project possible.

The Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project brings together a team of scholars, scientists, and librarians from Scotland, England, and the United States to study some of the most intriguing diaries and letters that David Livingstone ever produced. Because of the methods that Livingstone used, today much of these documents is illegible to the naked eye.

Since 2010, however, we have applied spectral imaging and processing – a cutting-edge imaging technology first pioneered by NASA – to study these documents, examine manuscript features that cannot be seen in any other way, and, indeed, reveal text that has been hidden for 140 years. The National Endowment for the Humanities (USA) has cited this project as one "that changed the landscape of the humanities" and has selected it as one of 50 projects to represent the best of the 65,000 projects that the NEH has funded since its inception 50 years ago.

Bonus: View all the documents to which the Livingstone Online team has applied spectral imaging

In 1870 and 1871, David Livingstone's travels took him far into central Africa, west of Lake Tanganyika into what is today eastern Congo. There, due to illness, difficult environmental conditions, and the reluctance of local African populations to assist him, he became stranded. He stopped first in a village called Bambarre, where "flesh-eating ulcers on the feet" halted progress for many months. Then he reached Nyangwe, which lies on the right bank of a principal tributary of the Congo River but which, Livingstone hoped, might have some connection to the mythical "source" of the Nile.

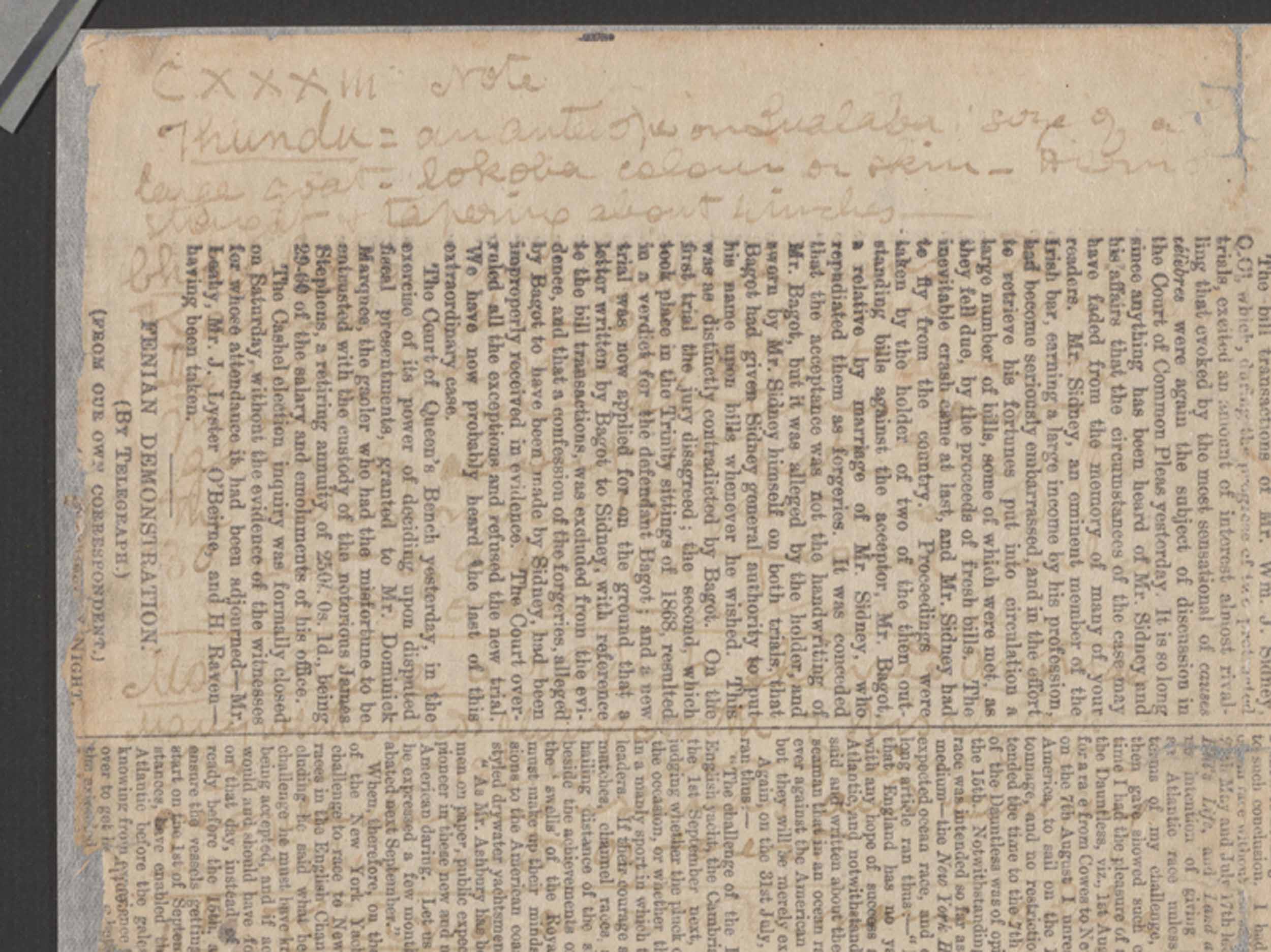

A page from David Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary before spectral imaging, detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported

As time passed, his supplies dwindled. First, Livingstone ran short of the small reporter's notebooks in which he recorded his field notes. So he started ripping pages out of the books he had with him and writing crosswise over the printed text. Next he turned to newspapers. Finally, he resorted to anything he had at hand – the back of a map, an envelope, any odd scrap of paper. Then he ran out of ink, so he turned the berries of a local plant, which he called "Zingifure" (today known as bixa orellana) to create a new reddish ink.

These expedients enabled him to keep writing. He described the ethnic groups he met in central Africa, none of whom had ever before seen a European. He wrote about local trade – visiting the periodic barter market in Nyangwe became one of his favorite ways to pass the time. He recorded vocabulary from local dialects he had never heard before. He noted sightings of unusual animals, including gorillas. Most importantly, Livingstone described some of the darkest months in his life – a period of isolation, when he believed that his friends and country had forgotten him, and when he witnessed a series of atrocities perpetrated by slave traders from Zanzibar. These atrocities culminated in a massacre in Nyangwe that left some 300-400 Africans dead in one day.

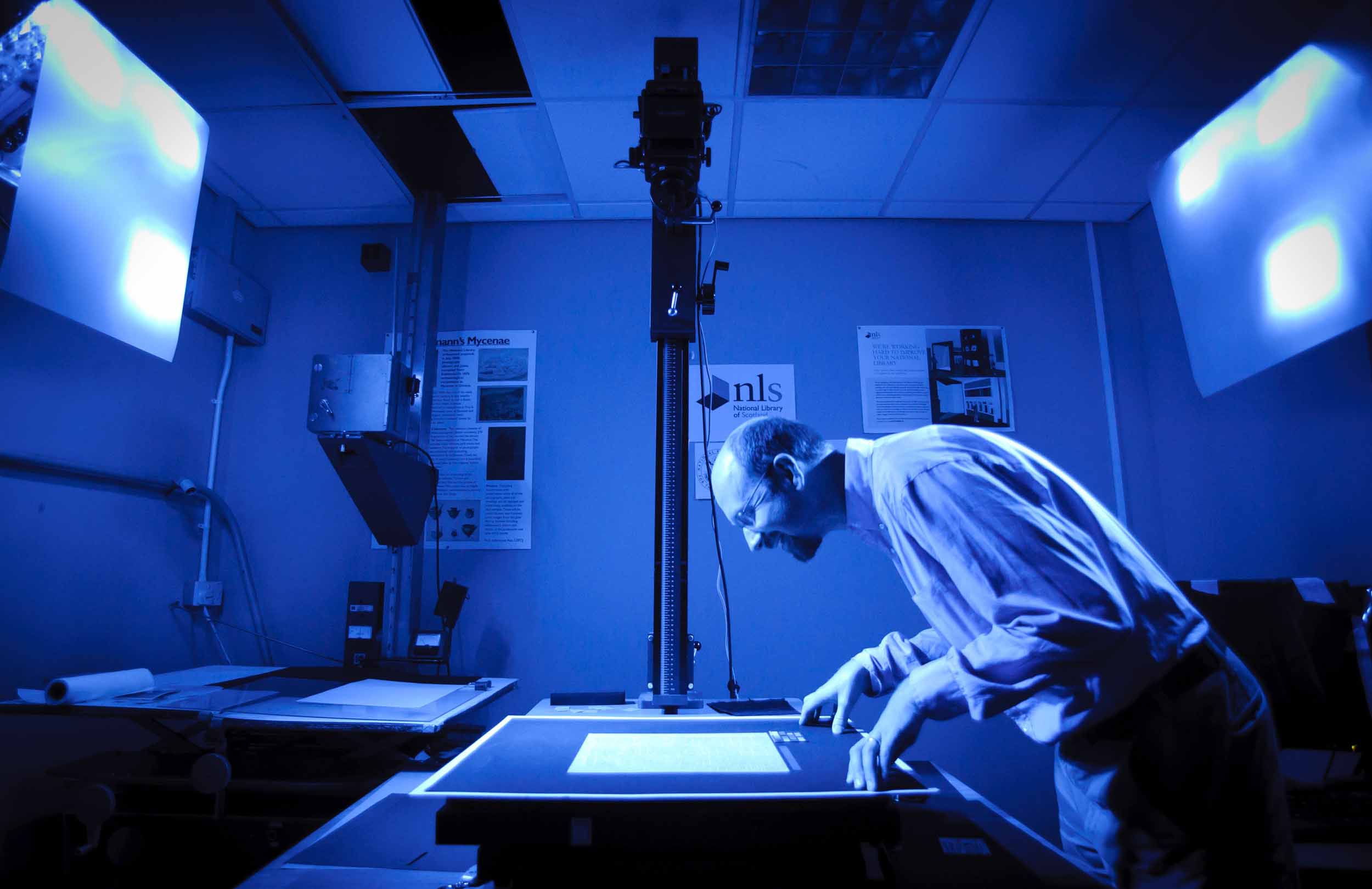

Adrian S. Wisnicki examines a page of Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary under spectral blue light. Copyright Callum Bennetts - Maverick Photo Agency. Used by permission.

When the documents arrived in Britain in 1870s – some were carried by Henry Morton Stanley, some smuggled out by individuals among the slave traders sympathetic to Livingstone's abolitionist views, some returned only with Livingstone's body after his death in Africa – Livingstone's words proved difficult and, in some cases, impossible to decipher. To record this period in Livingstone's life, sympathizers released only partial and edited transcriptions of the documents or turned to alternate sources, which offered revisionary versions of Livingstone's original experiences in Africa.

A chance turn of events in 2009 brought the Livingstone spectral imaging team together and set them on the path to recovering the full text of these letters and diaries. The story of that work and its exciting results – which have also been the subject of "The Lost Diary of Dr. Livingstone," a documentary broadcast by PBS in the US and National Geographic in the UK and Europe – is detailed in this section of Livingstone Online.

![Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_013723_0001-new-carousel_0.jpg)

![Processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's "Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal" (Livingstone 1870a:[3] pseudo_v4_BY), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's "Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal" (Livingstone 1870a:[3] pseudo_v4_BY), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000211_0003_pseudoBY_940_by_592-carousel.jpg)

![David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, [1869], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland: CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, [1869], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland: CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_003006_0001-new-carousel_0.jpg)