Project History

Cite page (MLA): Wisnicki, Adrian S., and Megan Ward. "Project History." In Livingstone's 1870 Field Diary. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. University of Maryland Libraries, 2017. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/c91df526-2079-4a89-888a-313ba71cb600.

This essay set outs the history of our work to develop a multispectral critical edition of Livingstone’s 1870 Field Diary and select 1870-71 manuscripts. It provides an overview of all significant periods of project endeavor and for each period describes all key project activities.

Introduction Top⤴

This essay provides a narrative of our collaborative, interdisciplinary research process and complements the documentation related to the development of the critical edition of Livingstone's 1870 Field Diary and select 1870-71 manuscripts. Livingstone would eventually revise the 1870 Field Diary into a segment of the Unyanyembe Journal (1866-73). In creating and editing the Last Journals (Livingstone 1874), however, Horace Waller focused on the 1870 Field Diary as his base text because the diary offered more detail for the period in question than the Unyanyembe Journal (1866-72). In describing our process in working with the original 1870 Field Diary and the related texts, the essay extends our efforts to conduct publicly-funded research in a transparent manner that promotes knowledge transfer and that opens all aspects of our research to critical review.

Groundwork (2010-13) Top⤴

The first phase (2010-13) of the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project demonstrated that spectral imaging could recover faded nineteenth-century text written over the pages of a newspaper. Image capture work in 2010 produced not only all the images of Livingstone’s 1871 Field Diary required for the first phase, but also all the images of the 1870 Field Diary, five 1871 letters, and the 1870 “Retrospect” necessary for a separate, second phase project on these texts.

However, since the latter three texts appeared fairly legible under natural light, Adrian S. WisnickiAdrian S. Wisnicki (Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska-Lincoln). Director of Livingstone Online, LEAP, and the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project., the director of the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project, gradually decided to turn the work of the second phase in a new direction by investigating whether spectral imaging could help scholars study the material features of these manuscripts.

(Top) The National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland. Copyright Livingstone Online. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. (Bottom) The David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre, Scotland. Copyright Angela Aliff. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. With one small exception, all the surviving fragments of the 1870 Field Diary reside at these two institutions.

Specifically, this approach raised a series of questions. Could spectral imaging reveal the history of these texts over the last century and a half? Could we use the technology to learn about a) the sequence in which Livingstone composed his works, b) the effect of the many individuals who had handled the texts before and after Livingstone’s death, and c) the impact of the multiple environments through which the manuscripts circulated?

To take up these questions, the project team, led by Wisnicki, submitted proposals to the Wellcome Trust, the Mellon Foundation, and Google in order to fund the development of this second phase. All these proposals proved unsuccessful. Yet despite time otherwise lost on such applications, the proposals did allow the team to hone their research objectives and refine the proposed project narrative.

Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward in London, 2015. Copyright Adrian S. Wisnicki. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported

The fortunes of the project team decisively turned for the better when Megan WardMegan Ward (Assistant Professor, Oregon State University). Co-director of Livingstone Online, LEAP, and the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project., also a Victorianist, joined the project (after reading about the project’s first phase on the NEH website) and when the team made a grant application for the NEH’s Scholarly Translations and Editions Grant on 6 December 2012. Ward brought a much-needed theoretical frame to the application of spectral imaging for studying material history.

The new application noted that the team hoped to use spectral image processing to “enhance illegible portions of Livingstone’s text, reveal manuscript topography, highlight environmental traces on the manuscript pages, and differentiate the inks used by Livingstone and others in correcting and marking up the text” and noted that “These features tell their own story about the construction and history of the manuscripts.” The team received news of the positive outcome of this application on 24 July 2013. A few months later, on 1 December 2013, the project launched.

Year One (1 Dec. 2013 to 30 Nov. 2014) Top⤴

The funded project, as designed, brought together a core set of four individuals for the main work – scholars WisnickiAdrian S. Wisnicki (Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska-Lincoln). Director of Livingstone Online, LEAP, and the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project. and WardMegan Ward (Assistant Professor, Oregon State University). Co-director of Livingstone Online, LEAP, and the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project., and two imaging scientists who had also played a key role in the first phase of the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project, Roger L. Easton Jr.Roger L. Easton Jr. (Professor, Chester F. Carlson Center for Imaging Science, Rochester Institute of Technology). One of the lead scientists for both phases of the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project. and Keith KnoxKeith Knox (Early Manuscripts Electronic Library). One of the lead scientists for both phases of the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project..

This core team, in turn, engaged a handful of people to provide strategic support, including TEI encoding specialist James CummingsJames Cummings (IT Services, University of Oxford). TEI specialist for Livingstone Online and the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project. and data manager Doug EmeryDoug Emery (Programmer, Schoenberg Institute of Manuscript Studies, University of Pennsylvania). Data manager for the first phase of the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project; honorary team member of the second project phase., although the latter left the project before it began in order to take a full-time position at the University of Pennsylvania. It was envisioned that the UCLA Digital Library would publish the materials of this phase, as it had of the previous phase.

The NEH grant narrative called for two principal deliverables:

1) [A c]omplete, interoperable electronic edition of Livingstone’s 1870 Field Diary and select 1871 manuscripts that reflects the scholarly, scientific, archival, and documentation standards established by the NEH funded electronic edition of Livingstone’s 1871 Field Diary.

2) All proposed edition underlying TIFF images, XML transcriptions, and metadata provided separately as “flat” files and integrated into the Livingstone Spectral Image Collection.

In other words, this new phase of the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project would publish the relevant digital materials in a manner consistent with and at a level of quality comparable to the first phase.

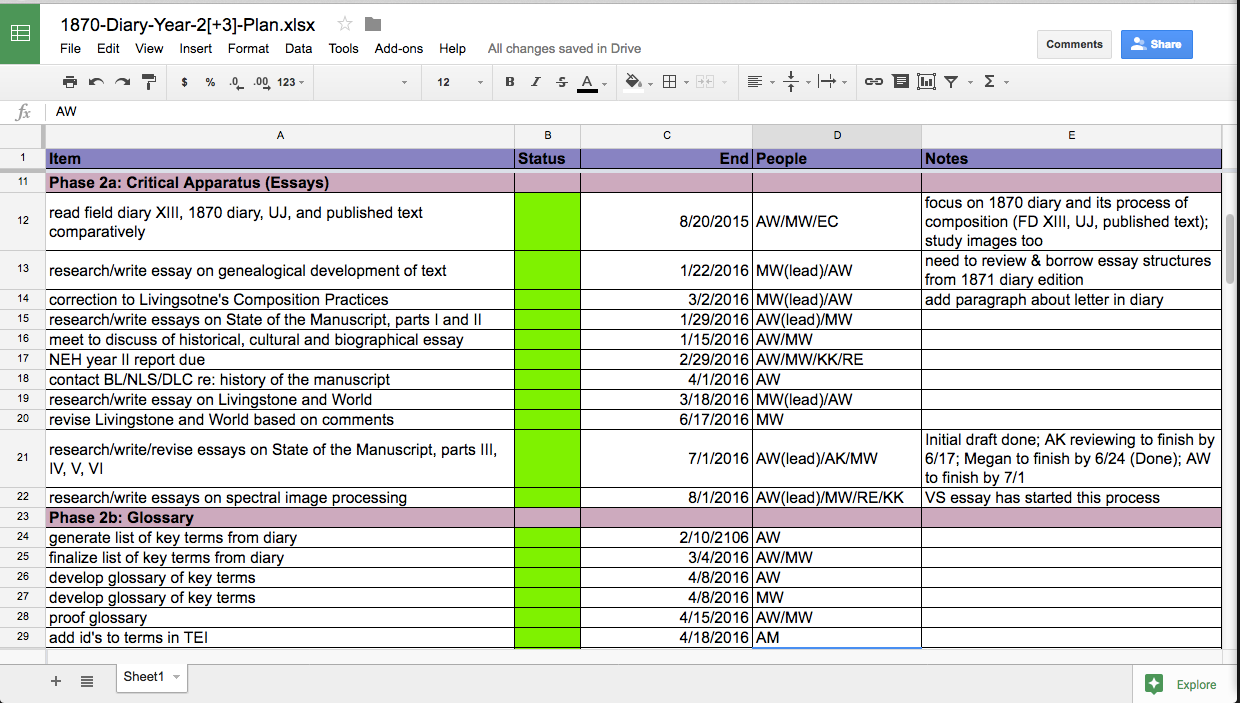

The Google docs version of the program plan used to guide the development of the present critical edition. Copyright Livingstone Online. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The plan, in this excerpt, tracks the development of critical materials over the span of a year (Aug. 2015-Aug. 2016).

To guide the work, in the first year of the project the team used the workplan provided in the NEH grant narrative. As a first step, WisnickiAdrian S. Wisnicki (Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska-Lincoln). Director of Livingstone Online, LEAP, and the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project. and WardMegan Ward (Assistant Professor, Oregon State University). Co-director of Livingstone Online, LEAP, and the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project. converted this plan into a streamlined program plan and, in doing so, determined to outline the work of the project on a yearly basis so as to be as responsive as possible to actual project progress. The two scholars then reviewed the first-year plan with the two scientists, finalized the plan, and the project formally got underway.

The first year of the project intermingled a series of foundational activities. To begin, Wisnicki and Ward examined existing spectral images of the 1870 Field Diary, the 1871 letters, and the 1870 “Retrospect” to identify regions of interests (ROIs) for new processing. They first linked the broad, grant narrative-defined processing objectives to multi-page segments of the manuscript. Then, as they began to transcribe the manuscript, they used the initial review to guide the identification of specific ROIs on each page. Finally, they extracted this data to spreadsheets that they shared and reviewed with the scientists in order to develop a prioritized spectral image processing task list.

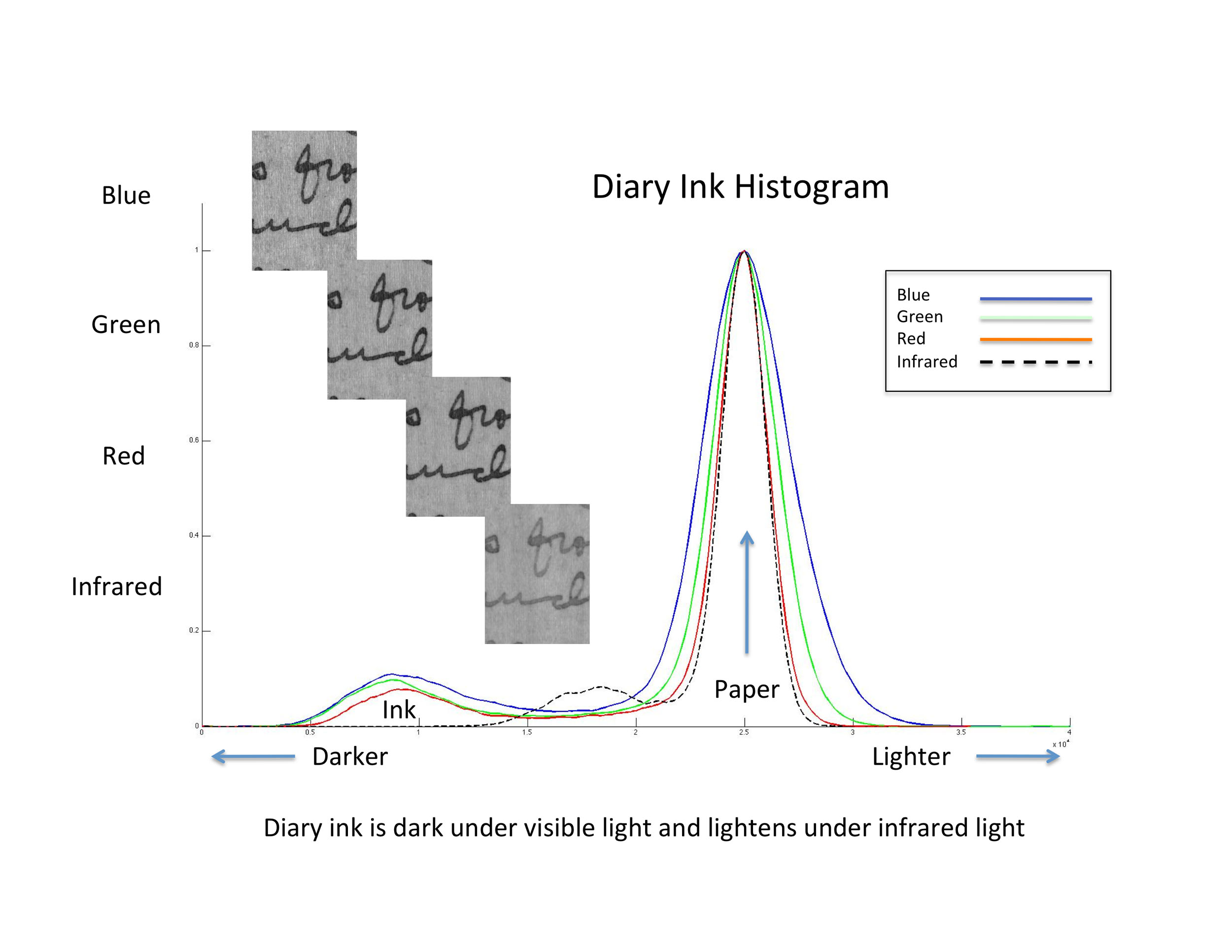

A histogram of ink spectra from the 1870 Field Diary that tracks the response of the ink under various wavelenghts of light. Copyright Keith Knox. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported

(For an overview of the processing methods used by the scientists, see the project history of the first phase of the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project.)

Once the scientists began processing the raw spectral images of the manuscripts, they used the task list as their guide for sequencing research. The workflow soon settled into a regular pattern. The scientists selected one or more prioritized tasks, then applied a variety of algorithms in an effort to address scholar needs. When ready, the scientists shared the results with the scholars who provided feedback.

Feedback took the form of written commentary as well as discussion during what soon became regular meetings. In other words, the workflow assumed an iterative and highly collaborative character that persisted till the end of the processing work in year two of the grant and became the basis of the project’s continuing momentum.

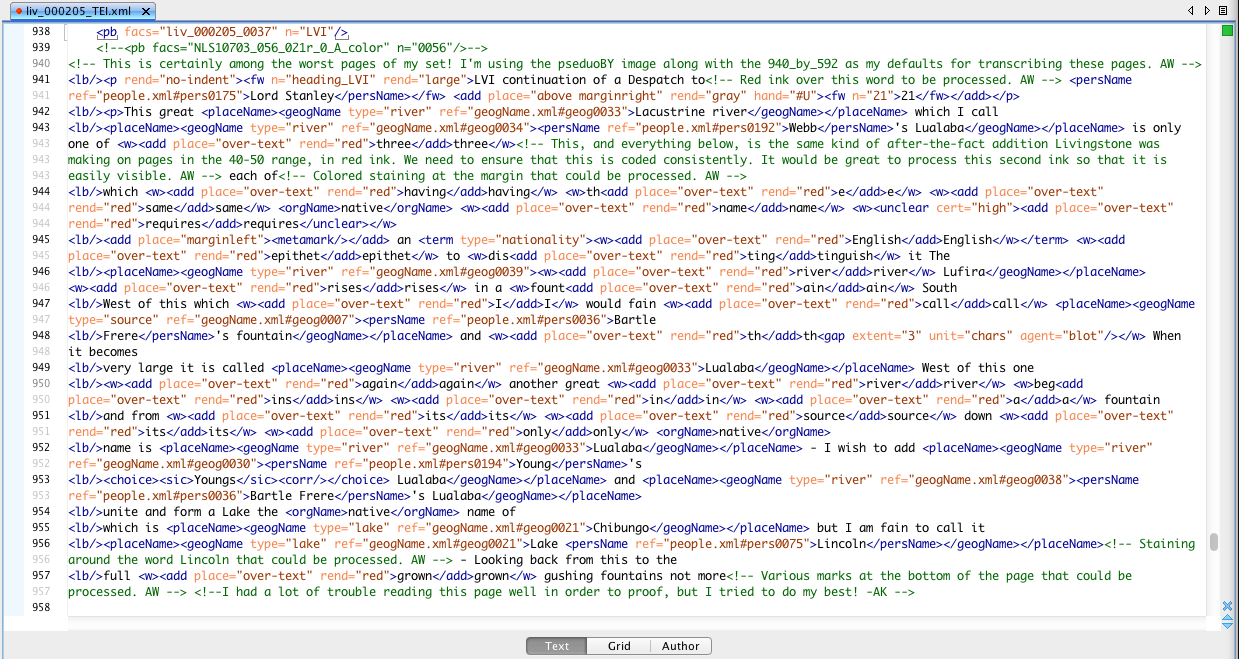

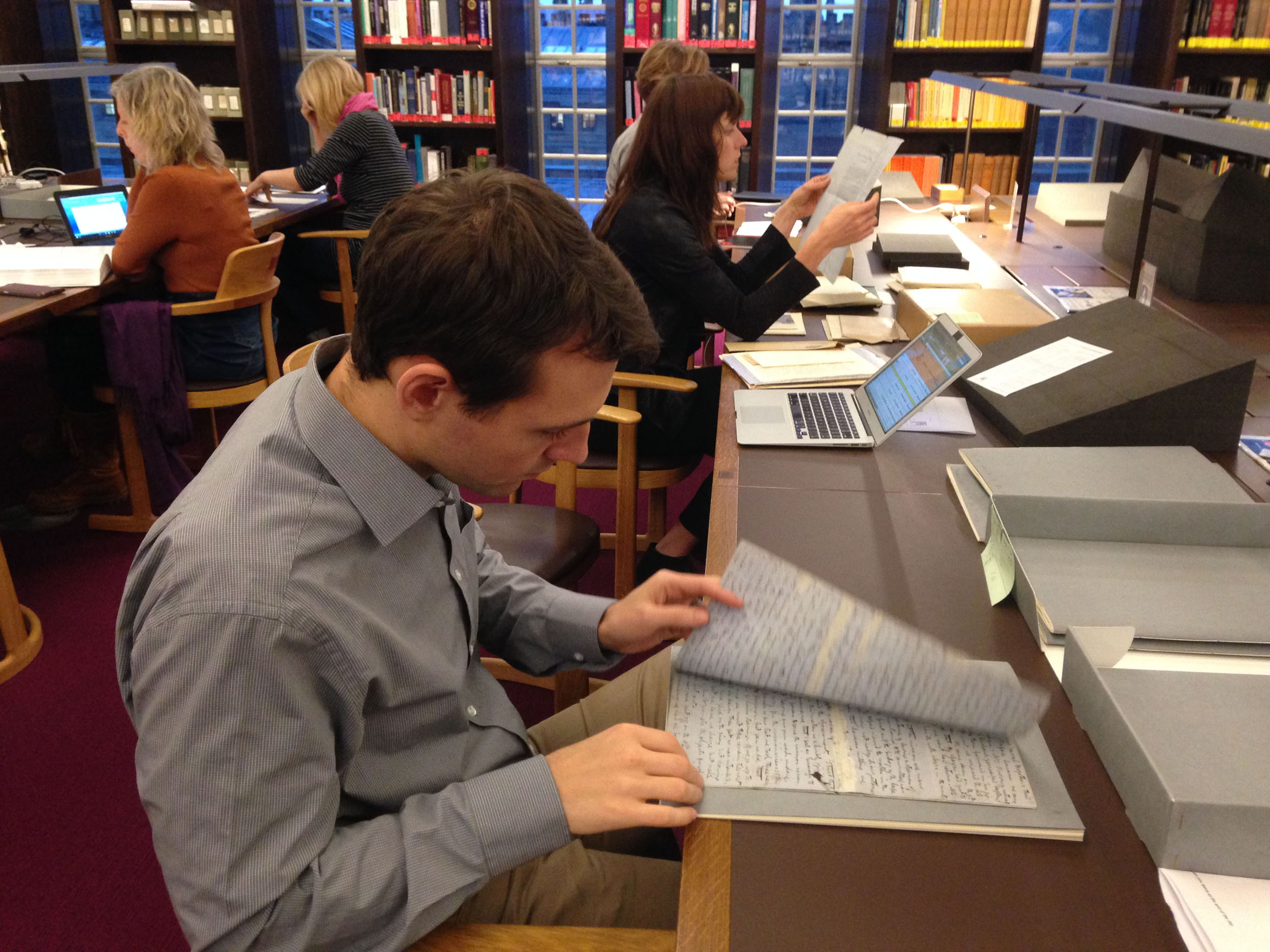

As image processing developed, WisnickiAdrian S. Wisnicki (Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska-Lincoln). Director of Livingstone Online, LEAP, and the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project. and WardMegan Ward (Assistant Professor, Oregon State University). Co-director of Livingstone Online, LEAP, and the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project. worked on transcribing, encoding, and annotating Livingstone’s manuscripts using the TEI P5 guidelines. The drafting of a detailed Livingstone manuscript coding manual through another NEH-funded project (LEAP: The Livingstone Online Enrichment and Access Project, 2013-17) considerably enhanced and facilitated this work, as did input from James CummingsJames Cummings (IT Services, University of Oxford). TEI specialist for Livingstone Online and the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project. on thorny coding questions and the assistance of Ashanka KumariAshanka Kumari (Doctoral Student, University of Louisville). Research assistant for Livingstone Online., Wisnicki’s graduate research assistant. Additionally, the work benefited from preliminary TEI transcriptions of the 1871 letters created by Wisnicki and Kate SimpsonKate Simpson (Research Associate, Queen's University Belfast). Associate project scholar and UK outreach coordinator for Livingstone Online. in the first phase of the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project.

Transcription of a segment of the 1870 Field Diary in XML TEI P5. Copyright Livingstone Online. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported

Thanks to these combined efforts, the scholars (Wisnicki, Ward, and now Kumari) succeeded in completing fully encoded and edited transcriptions of all relevant manuscripts by the end of the first year of the grant – a full six months ahead of schedule. (Note: The headers of individual transcription files for the 1870 Field Diary and 1870-71 texts provide additional detail about the stages of transcription and encoding for each item and the individuals involved in the process.) Transcription also resulted in initial research on the structure and composition of the 1870 Field Diary, although this research did not get fully underway until the second year of the grant.

As a result, the first year of the grant was quite productive. Although some unforeseen complications outside of the project’s purview delayed a handful of project tasks (most notably, image processing), the team nonetheless made solid and demonstrable progress towards realizing overall project objectives.

Year Two (1 Dec. 2014 to 30 Nov. 2015) Top⤴

The project team began the second year of the grant like they did the first, by using the NEH grant application workplan to develop a program plan for the coming year. With the plan in place, the core team carried on with its regular meetings and continued to address spectral image processing objectives.

The image processing work produced excellent results and by the end of the second project year, the team had completed nearly all objectives set out in the grant. KnoxKeith Knox (Early Manuscripts Electronic Library). One of the lead scientists for both phases of the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project. and EastonRoger L. Easton Jr. (Professor, Chester F. Carlson Center for Imaging Science, Rochester Institute of Technology). One of the lead scientists for both phases of the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project., in consultation with WisnickiAdrian S. Wisnicki (Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska-Lincoln). Director of Livingstone Online, LEAP, and the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project. and WardMegan Ward (Assistant Professor, Oregon State University). Co-director of Livingstone Online, LEAP, and the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project., produced a broad assortment of spectral images that ultimately facilitated detailed study of manuscript elements such as composition, handling, and preservation (see the six-part State of the Manuscript essay).

Animation of a plot of ink spectral curves from a segment of a single page of the 1870 Field Diary manuscript (Livingstone 1870i:XXXI). Copyright Keith Knox. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The curves, as indicated at left, cluster around three slopes: the paper (top) and two kinds of inks. As the animation plays, a yellow vertical line moves across these curves and the corresponding colors and values of the curves appear on the graph at right.

Moreover, the ongoing and extensive discussions between the scholars and the scientists resulted in additional benefits. The discussions enabled the team to examine the production history of Livingstone’s manuscript in a robust, detailed, and highly interdisciplinary manner that, later, considerably influenced critical analysis (again, as exemplified in project’s six-part State of the Manuscript essay). Regular meetings also kept the project on point, helped clarify both scholar research questions and scientists processing capabilities, and, ultimately, led to the introduction of new processing techniques that significantly enhanced project work.

Alongside such research, Wisnicki, Ward, KumariAshanka Kumari (Doctoral Student, University of Louisville). Research assistant for Livingstone Online., and Erin CheathamErin Cheatham (Graduate Student, University of Nebraska-Lincoln). Research assistant for Livingstone Online. (another of Wisnicki’s graduate research assistants at UNL) continued with their critical encoding of Livingstone’s manuscripts and the development of critical materials. In the second year, the scholars encoded the portions of Agnes Livingstone’s transcription of the 1870 Field Diary for which original pages did not survive and encoded the sections of the Last Journals (1874) corresponding to the 1870 Field Diary.

Erin Cheatham and Adrian S. Wisnicki at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 2016. Copyright Angela Aliff. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported

Through LEAP, their other NEH grant, the scholars also transcribed the portion of Livingstone’s Unyanyembe Journal (1866-72) that corresponded to the 1870 Field Diary. As a final step in the encoding process, Heather F. BallHeather F. Ball (Project Cataloger, The Morgan Library & Museum). Coordinating Associate Project Scholar for Livingstone Online., associate project scholar for Livingstone Online, integrated all transcriptions to overall site standards.

These collective encoding accomplishments would enable the team to publish the most complete version of the 1870 Field Diary possible and would also allow for comparative study of the Livingstone’s original manuscript with the revised versions from his journal and the posthumously edited, published version of the text.

Additionally, the scholars undertook extensive work on a glossary of key terms cited in Livingstone’s 1870-1871 manuscripts, ultimately identifying and/or defining some 500 distinct people, groups, places, and geographical features. Research for the glossary helped enhance the existing encoded transcriptions, clarified geographical details, and facilitated the scholars in understanding some of the complex social relationships among the many African and Arab individuals cited in Livingstone’s texts.

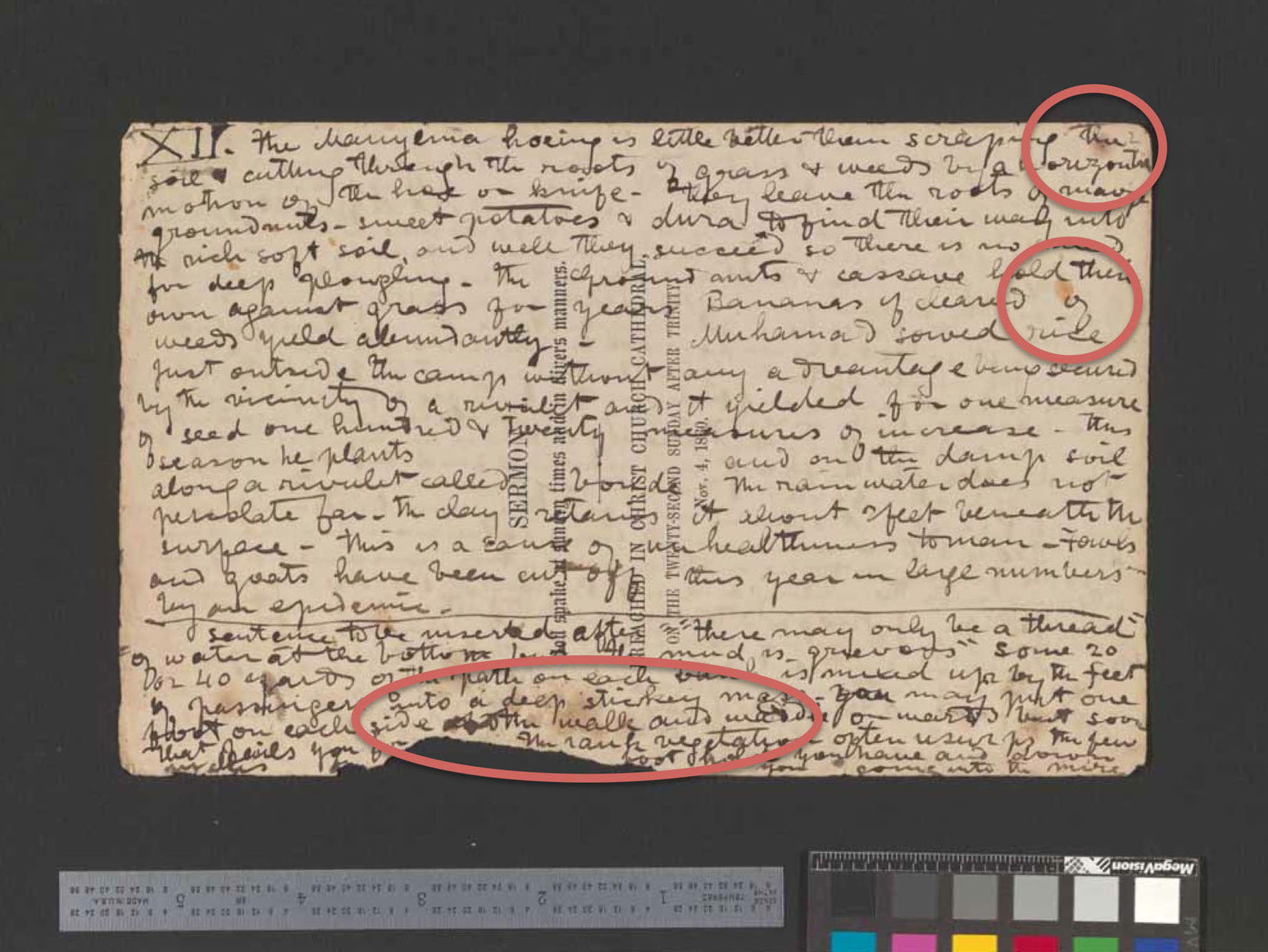

PowerPoint slide of the 1870 Field Diary with regions of interest (ROIs) circled - stains in this case. Copyright Livingstone Online. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The team used such slides, first, to guide spectral image processing and, second, to support critical analysis.

The scholars pursued this research while completing an essay on Livingstone’s composition methods during the period in question, writing the first two parts of what would eventually become the six-part State of the Manuscript essay, and commencing research on an essay on Livingstone's sources. Additionally, Alex MunsonAlex Munson (Graduate Student, University of Nebraska-Lincoln). Research assistant for the critical edition of Livingstone's 1870 Field Diary and select 1870-71 manuscripts., another graduate research assistant, provided research support for the State of the Manuscript essay.

As a means to disseminating research, the second year of the project included a week-long visit to stakeholder institutions in the UK, and a presentation on the project at the annual North American Victorian Studies Association conference (NAVSA, July 2016). WardMegan Ward (Assistant Professor, Oregon State University). Co-director of Livingstone Online, LEAP, and the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project. also delivered an invited talk to P19, the Philadelphia Nineteenth-Century Studies Group.

The UK trip created the opportunity for in-person consultation of the 1870 Field Diary and another diary related to the project (Livingstone 1869) at the National Library of Scotland and to engage in dissemination activities in the form of meetings with David Livingstone Centre staff and meetings and lectures at the National Library of Scotland and the British Library.

Team and stakeholder meeting over lunch at the David Livingstone Centre, 2015: (from left) Megan Ward, Adrian S. Wisnicki, Angela Aliff, Anne Martin, and Kate Simpson. Copyright Angela Aliff. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported

The NAVSA paper, which WisnickiAdrian S. Wisnicki (Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska-Lincoln). Director of Livingstone Online, LEAP, and the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project. delivered on behalf of the project team, became one of nine such papers selected to represent the conference in a special 2016 issue of Victorian Studies – a recognition of the project preliminary results.

Finally, during the project’s second year, the team began to plan publication of the critical edition. When the team submitted its original NEH application in December 2012, it did not anticipate that this project and the team’s other application to the NEH (for LEAP) would both be funded, as they were. This turn of events had significant positive implications in the context of the proposed critical edition.

For instance, the redevelopment of Livingstone Online through LEAP eliminated the need for an independently developed edition interface for 1870 Field Diary and 1870-71 manuscripts because the edition could now be embedded in Livingstone Online. Moreover, since both NEH projects ran concurrently, the project team not only had the chance to draw on other capabilities developed for LEAP, such as the Livingstone Online coding manual, but also to develop core spectral image data in line with Livingstone Online practices, a fact that would later enable the straightforward addition this image data to Livingstone Online’s digital collection.

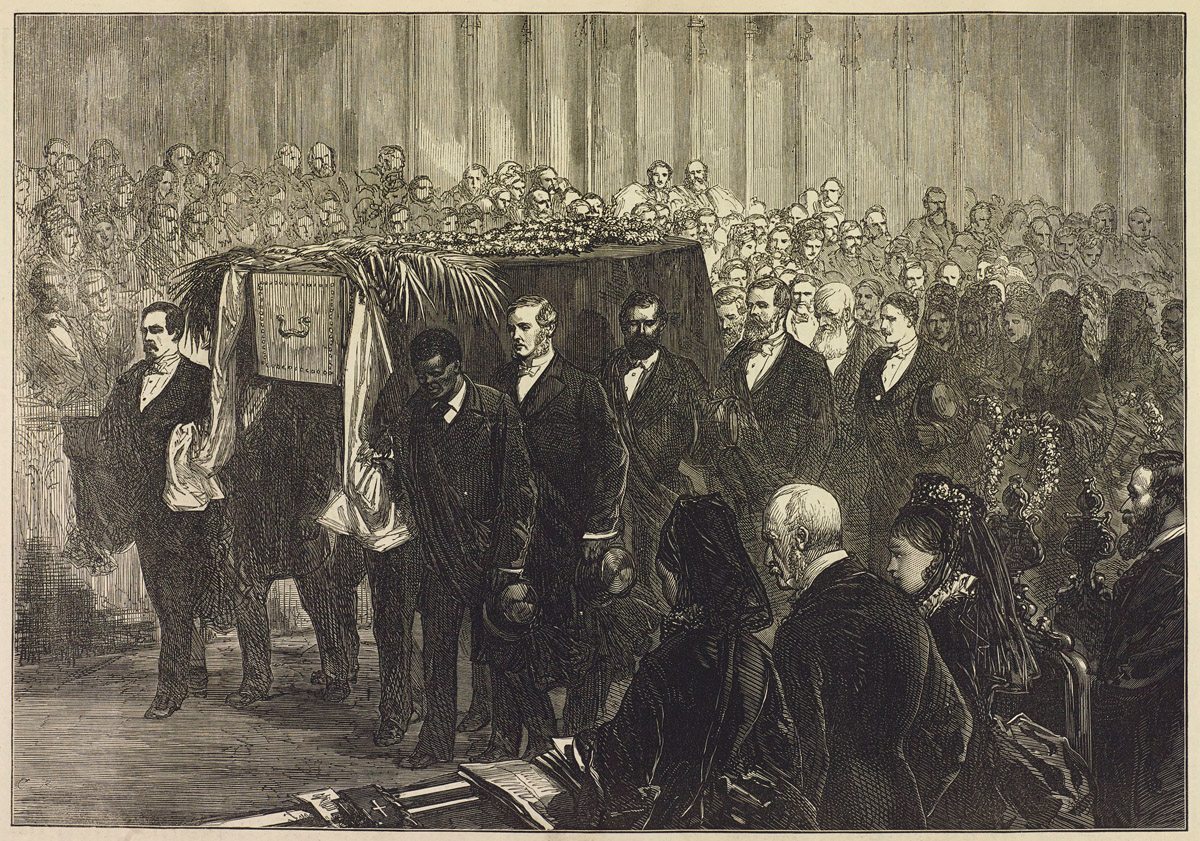

'Funeral of Dr. Livingstone in Westminster Abbey.' Illustration from a review of Livingstone's Last Journals in the Illustrated London News, 64 (1874): 401. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. Livingstone carried the 1870 Field Diary with him until his death in central Africa in 1873. The diary then accompanied his body to Britain where Livingstone received a burial in one of Britain's most important churches, while his heirs distributed the diary to a number of Britain's leading archives.

Such collaborations gave the team a significant head start on edition interface development for the 1870 Field Diary and select 1870-71 manuscripts. This also enabled WisnickiAdrian S. Wisnicki (Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska-Lincoln). Director of Livingstone Online, LEAP, and the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project. and WardMegan Ward (Assistant Professor, Oregon State University). Co-director of Livingstone Online, LEAP, and the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project. to turn their attention – during the last months of 2015 and the beginning of 2016 – to transitioning Livingstone Online (and, by default, the second phase of the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project) from the UCLA Digital Library to the University of Maryland Libraries.

This transition resulted from complications in the collaborative relationship with UCLA to be discussed in the final part of the LEAP project history. The immediate results of these complications, beyond the shift to the new hosting institution, entailed the addition of programmer Nigel BanksNigel Banks (Independent programmer). Lead developer for the critical edition of Livingstone's 1870 Field Diary and select 1870-71 manuscripts. to both project teams to replace UCLA for Islandora development and, separately, a decision by Wisnicki (in collaboration with core team members on both projects) to extend each of the two grants by a year in order to ensure that both grants met all application narrative commitments in full.

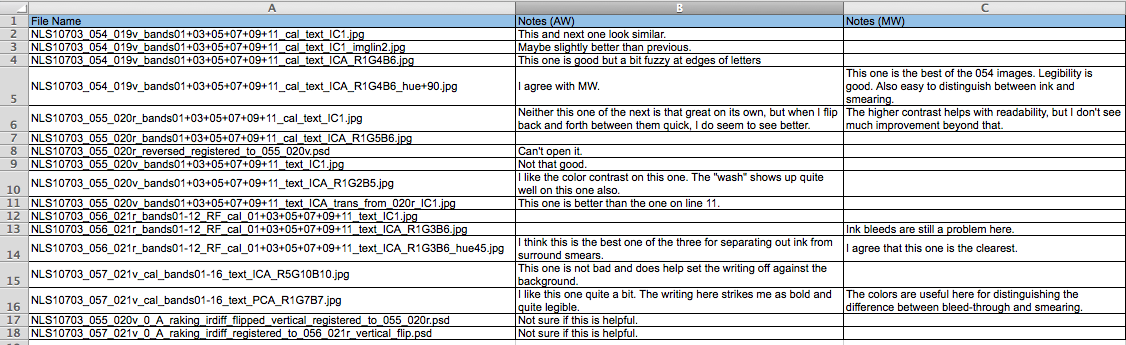

Spreadsheet recording feedback from Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward on a series of spectral images produced by Roger L. Easton Jr. Copyright Livingstone Online. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported

Consequently, despite the need for an extension, the spectral imaging project team continued to make solid progress during the second year of the grant, especially in areas such as image processing, critical encoding, developing critical materials, building core data, and disseminating results to stakeholders and specialists. This work both advanced project goals considerably and, in all cases, met or exceeded the standards of scholarship set by the first project phase on Livingstone’s 1871 Field Diary.

Year Three (1 Dec. 2015 to 31 Dec. 2016) Top⤴

By the beginning of the third project year, the team had successfully developed nearly all the most important core data, including required spectral images and critically encoded versions of all relevant manuscripts.

In the third year, therefore, project scholars WisnickiAdrian S. Wisnicki (Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska-Lincoln). Director of Livingstone Online, LEAP, and the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project. and WardMegan Ward (Assistant Professor, Oregon State University). Co-director of Livingstone Online, LEAP, and the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project. (with assistance from KumariAshanka Kumari (Doctoral Student, University of Louisville). Research assistant for Livingstone Online.) turned to the written analysis of this data. Working at a steady pace, the scholars completed in succession:

1. the essay, Livingstone’s Global Sources;

2. the last four parts of the State of the Manuscript essay;

3. final research on the glossary;

4. the addition of tags to the transcriptions that allowed all glossary entries to appear as tooltips when the transcriptions were published online;

5. a manuscript citation and file naming guide;

6. a comprehensive bibliography for both phases of the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project; and

7. an introduction to the second phase of the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project as a whole.

In addition, Wisnicki developed the XSL and CSS files needed to display all edited and encoded texts online, assembled all project documentation, and worked with Ward to write an introduction to the documentation and to draft the present project history. During this time, Anne MartinAnne Martin (Archivist, David Livingstone Centre). Associate director of Livingstone Online. (David Livingstone Centre) and Alison MetcalfeAlison Metcalfe (Manuscripts Curator, National Library of Scotland). Institutional contact for Livingstone Online. (National Library of Scotland) also helped the team with questions related to the documented archival history of the 1870 Field Diary and 1870-71 manuscripts.

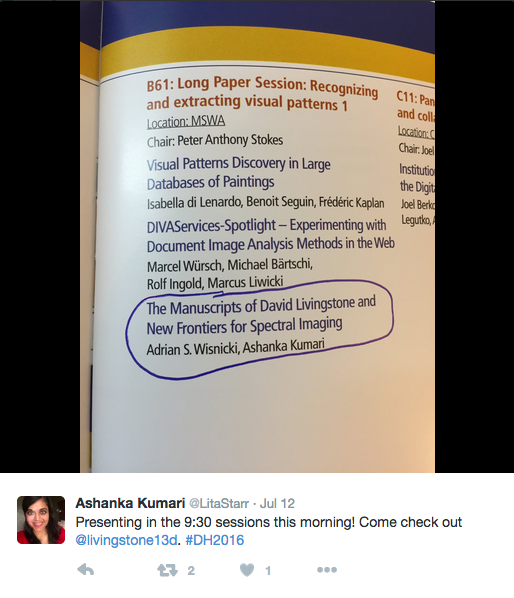

| Twitter posts on Ashanka Kumari and Adrian S. Wisnicki's presentation at DH2016 in Krakow, Poland. Copyright Ashanka Kumari. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported |

KumariAshanka Kumari (Doctoral Student, University of Louisville). Research assistant for Livingstone Online. and Wisnicki also delivered talks on the project at DH2016, the major conference in the field of digital humanities. These talks set out project results to a broad range of digital humanists and introduced the animated spectral image production methodology that Kumari had developed and subsequently wrote up for the current edition.

Concurrently with this stream of critical activity, EastonRoger L. Easton Jr. (Professor, Chester F. Carlson Center for Imaging Science, Rochester Institute of Technology). One of the lead scientists for both phases of the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project. and KnoxKeith Knox (Early Manuscripts Electronic Library). One of the lead scientists for both phases of the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project. completed the vast majority of processing tasks and collaborated with the scholars on an extensive, annotated enumeration of all processed spectral images produced for the two phases of the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project plus the pilot project on Livingstone’s Letter from Bambarre (2010-12).

As spectral image data came in, Wisnicki led the integration of all spectral images and transcriptions, added detailed metadata to image headers, and built downloadable archival packets that would allow users to interact with this data independently of the project. In this work, Wisnicki received key assistance from Doug EmeryDoug Emery (Programmer, Schoenberg Institute of Manuscript Studies, University of Pennsylvania). Data manager for the first phase of the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project; honorary team member of the second project phase. (who continued to advise the project despite having formally left it) and was also aided by Jessica DussaultJessica Dussault (Programmer/Analyst II, Center for Digital Research in the Humanities, University of Nebraska-Lincoln). Data developer for the critical edition of Livingstone's 1870 Field Diary and select 1870-71 manuscripts. who developed a series of scripts to refine and manipulate the metadata.

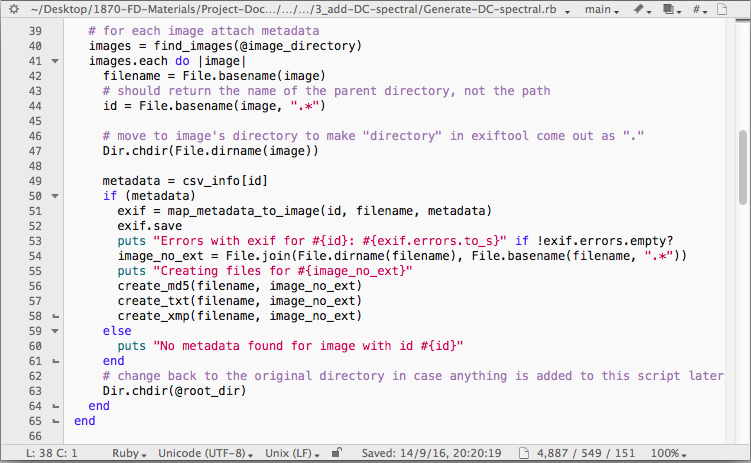

Excerpt of the Ruby script created by Jessica Dussault to add Dublin Core metadata to the headers of the TIFF spectral images. Copyright Jessica Dussault. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported

Finally, WisnickiAdrian S. Wisnicki (Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska-Lincoln). Director of Livingstone Online, LEAP, and the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project. and WardMegan Ward (Assistant Professor, Oregon State University). Co-director of Livingstone Online, LEAP, and the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project. and, separately, Wisnicki and BanksNigel Banks (Independent programmer). Lead developer for the critical edition of Livingstone's 1870 Field Diary and select 1870-71 manuscripts. turned to development of the interface. Ward, working with Wisnicki, first converted all critical materials to Drupal while embedding them in the Livingstone Online site. Wisnicki then selected and added all illustrative materials, with an eye to highlighting the complex, intercultural legacy of Livingstone’s 1870-71 manuscripts from the nineteenth century to the present day. The illustrative images included many created by Angela AliffAngela Aliff (Graduate Student, Indiana University of Pennsylvania). Research assistant and interface designer for Livingstone Online. for the Livingstone Online project as a whole. Once the scholars had finalized individual webpages, Lauren GeigerLauren Geiger (Graduate Student, University of Nebraska-Lincoln). Research assistant for the critical edition of Livingstone's 1870 Field Diary and select 1870-71 manuscripts., another of Wisnicki’s graduate research assistants, conducted a final review of each page.

Through detailed discussion, Wisnicki also collaborated with Banks on planning the technical creation of the edition in Islandora. The subsequent development, led by Banks, entailed creating a special content type to accommodate critical editions within Livingstone Online, implementing a spectral image content model on the back end of the site, and enabling the batch uploading and replacing of spectral image files.

Nigel Banks (foreground) and Megan Ward (background) at the Weston Library, Oxford with Livingstone manuscripts, 2016. Copyright Adrian S. Wisnicki. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported

Banks also built a dynamic image viewer for Livingstone Online, then enhanced this viewer to facilitate user review of multiple spectral images for each page of the manuscript. As a last step, Banks created a Drupal page that would enable comparative study of encoded versions of the 1870 Field Diary and the corresponding segments of the Unyanyembe Journal (1866-72), and the Last Journals (1874).

Thanks to these efforts over the three-year period of the grant, the beta version of the critical edition of Livingstone’s 1870 Field Diary and select 1870-71 was released by the project team on 16 November 2016. To mark the release, US-based members of the team traveled to the UK to meet with UK-based collaborators and to deliver a series of presentations on the project at stakeholder institutions. These included lectures at the University of Edinburgh (14 November 2016), the University of Oxford (16 November 2016), and Queen's University Belfast (18 November 2016).

(From left:) Justin Livingstone, Adrian S. Wisnicki, Kate Simpson, Keith Knox, Megan Ward, and Roger L. Easton, Jr. after presenting at Queen's University Belfast on 18 November 2016. Copyright Justin Livingstone. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported

The beta release "tour" gave team members from alternate sides of the Atlantic a chance to review the project face-to-face, to discuss results with representatives from these institutions as well as the David Livingstone Centre, the National Library of Scotland, and the Royal Geographical Society, and, finally, to explore the possibility of applying advanced spectral image processing to other UK-based Livingstone manuscripts as well as objects collected during Livingstone’s travels. (Read the blog post on the "tour" here). During the tour, the team also planned for the release of the formal first edition of the project (which would include additional critical materials and would correct site bugs, typos, and other such minor issues). Finally, the team released the first edition in April 2017, thereby formally bringing the project to an end.

Conclusion Top⤴

The project to produce a multispectral critical edition of Livingstone's 1870 Field Diary lasted just over three years. Given the scale and complexity of the endeavor, the project ran exceptionally smoothly end-to-end. We attribute this to three factors. First, the commitment of our team members, which resulted in consistent, incremental development throughout the project’s life span. Second, Wisnicki and Ward's joint directorship brought different critical frameworks to the project that enriched the final edition. And finally, our project's multigenerational, interdisciplinary approach resulted in insights that could only emerge from scientists and literary critics, junior and senior scholars, working truly collaboratively.

Editor's Note: In 2018, the project team submitted the edition to the Modern Language Association (MLA) for peer review and to be considered for a seal from the Committee on Scholarly Editions. Edward Whitley (Lehigh University) kindly agreed to serve as the edition vetter on behalf of the MLA, while Noelle A. Baker (Independent Scholar) took the role of review manager; Laura Kiernan (MLA) facilitated the inspection as the Committee's staff liaison.

Whitley delivered his report in late February 2019 and recommended the edition be awarded the MLA seal in the following terms:

"Livingstone’s 1870 Field Diary and Select 1870-1871 Manuscripts is an excellent contribution to the already superb Livingstone Online project. The Livingstone Online team should be commended both for their scrupulous attention to best practices in electronic scholarly editing and for their innovative use of spectral imaging technologies. This is a masterwork of scholarly editing for an important text that presents numerous challenges to conventional editorial methodology. Livingstone’s 1870 Field Diary and Select 1870-1871 Manuscripts should, without question, be recognized for having lived up to the highest standards put forward by the MLA Committee on Scholarly Editions. I recommended that the edition be awarded the CSE seal."

The project team was, of course, delighted with this assessment. Whitley also recommended that a handful of minor enhancements be made to improve the edition. The project team soon implemented these enhancements and submitted a formal response to the MLA outlining the site changes made based on Whitley's feedback. Finally, on 18 April 2019, the team learned that the edition had been awarded the seal designating the edition as an MLA Approved Edition. The seal now appears on the home page of the edition.

Animated spectral image (ASI) of a page of the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871a:LXXVI [v.1]) created by Adrian S. Wisnicki for testing purposes. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. In a nod to the present multispectral critical edition, the image cycles through the colors of the visible light spectrum and, in doing so, reveals different layers of text and staining on the page.

![Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_013723_0001-new-carousel_0.jpg)

![Processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's "Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal" (Livingstone 1870a:[3] pseudo_v4_BY), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's "Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal" (Livingstone 1870a:[3] pseudo_v4_BY), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000211_0003_pseudoBY_940_by_592-carousel.jpg)

![David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, [1869], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland: CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, [1869], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland: CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_003006_0001-new-carousel_0.jpg)

![Animated spectral image (ASI) of a page of the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871a:LXXVI [v.1]) created by Adrian S. Wisnicki for testing purposes. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). Animated spectral image (ASI) of a page of the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871a:LXXVI [v.1]) created by Adrian S. Wisnicki for testing purposes. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/project-history/LXXVI-rainbow1-small-article.gif)