Livingstone's Global Sources

Cite page (MLA): Ward, Megan, and Adrian S. Wisnicki. "Livingstone's Global Sources." In Livingstone's 1870 Field Diary. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. University of Maryland Libraries, 2017. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/c7a7c0e0-6b8a-40fb-ba23-984487fede29.

Livingstone represented his last journey (1866-1873) as a search for the geographical source(s) of the Nile, but the 1870 Field Diary foregrounds Livingstone’s encounter with sources of another kind: non-Western informants who shared their knowledge of local African geography and cultural practices. Attention to Livingstone’s use of these sources illuminates broader strategies by which Victorian travel writers converted experiences – over which they sometimes exerted limited influence – into authoritative and controlled narratives of the field.

Introduction Top ⤴

Livingstone’s 1870 Field Diary reflects a range of information sources although most of the diary details Livingstone’s time spent in one place, the central African village of Bambarre, where he was immobilized due to ill health. In this, the diary arguably offers an excellent snapshot of Livingstone’s experiences in a “contact zone,” Mary Louise Pratt’s seminal term for the “social spaces where disparate cultures meet, clash, and grapple with each other, often in highly asymmetrical relations of domination and subordination” (Pratt 1992:24).

In the decades since Pratt’s work, scholars have worked to add nuance to this understanding of contact narratives by resisting a simple tale of domination and subordination while identifying the dialogue and cooperation that existed alongside the "clash[ing], and grappl[ing]" that Pratt identified. One historian, for instance, has argued that “Much of the information brought back by explorers was derived from what Africans told them” (Bridges 1998:73). This has given rise to the problem of how best to "acknowledge the ethical value of dialogue” between colonizer and colonized “without erasing from view the uneven relations of domination and resistance characteristic of modern colonialism and imperialism" (Barnett 1998:240).

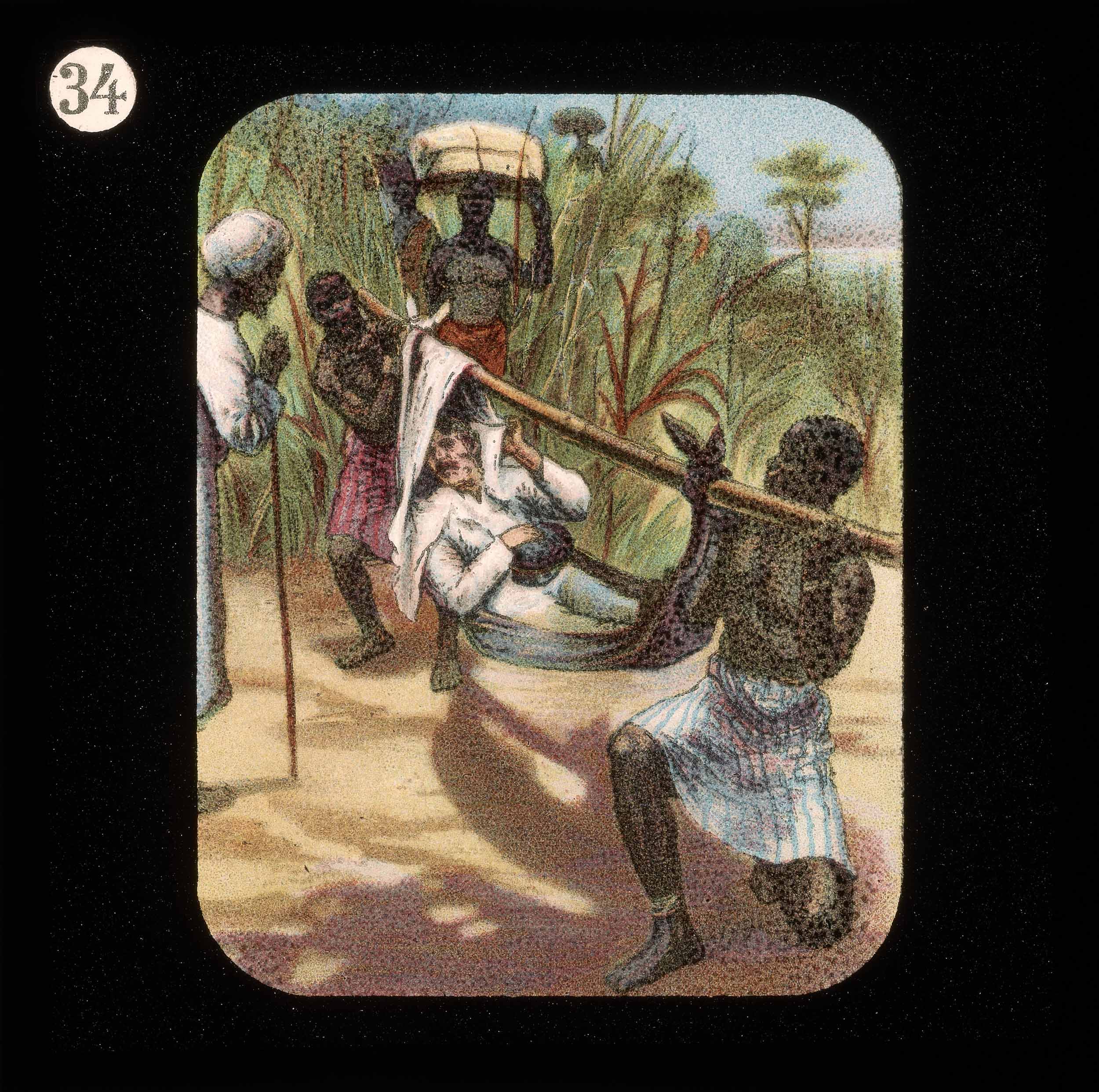

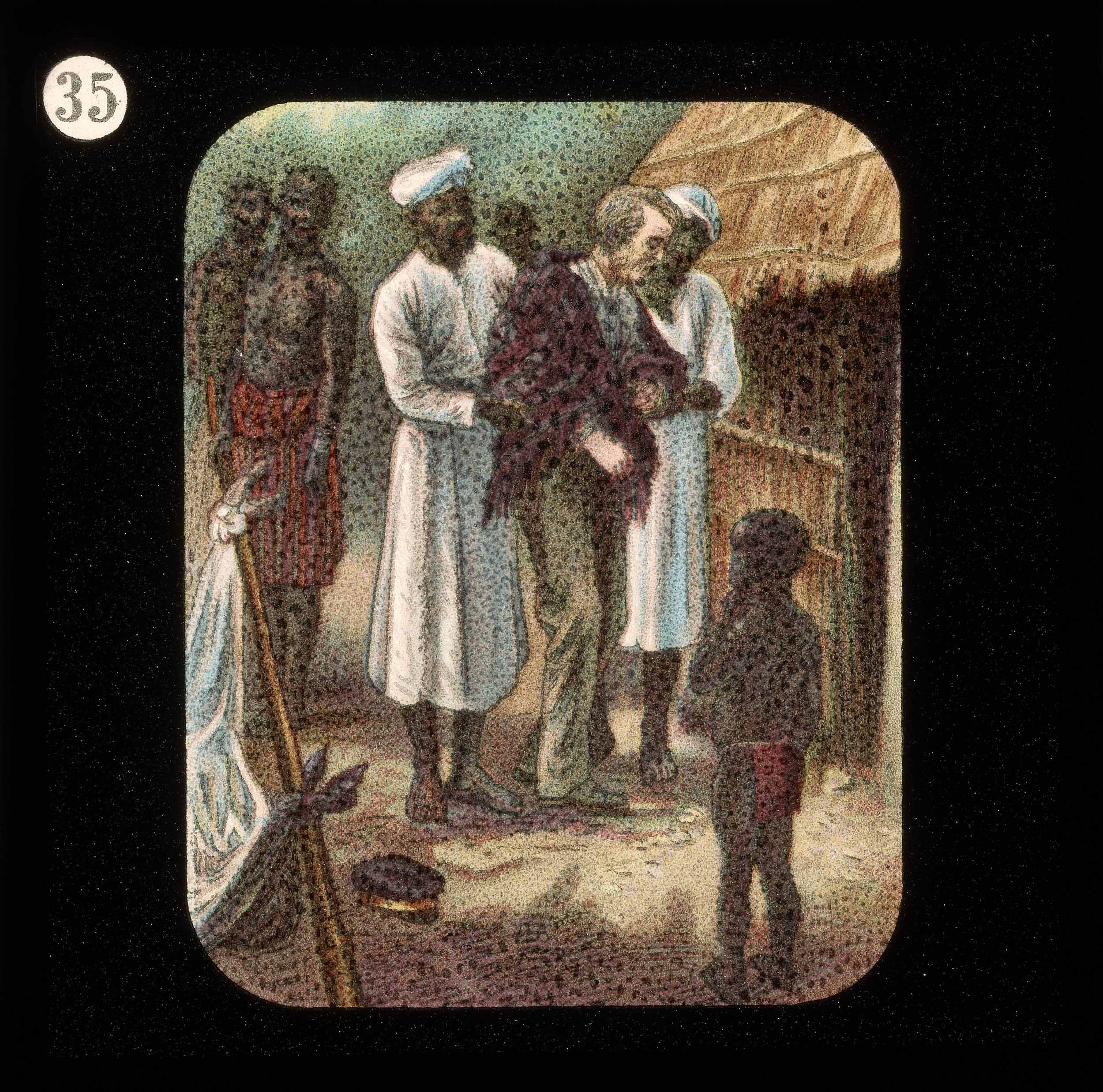

| Lantern Slides of the Life, Adventures, and Work of David Livingstone, Date Unknown (c.1900). Courtesy of the Smithsonian Libraries, Washington, D.C. During his last journey (1866-73), Livingstone continuously relied on his African and Arab companions to support all aspects of his travels. These slides romanticize that relationship, while other depictions ignore it altogether. |

Livingstone has long acted as a kind of lightning rod for this problem, as his role in relation to imperial oppression continues to be debated (J. Livingstone 2014). Critics have variously interpreted the assistance that Livingstone received from local African populations, Arab traders, Indian financiers, and others as either reinforcing or undermining the colonial power dynamic. To some critics, this “appropriation” tends to “see African compliance in the colonial enterprise as affirming a spiritual and familiar bond between colonizer and colonized” (Spurr 1993:33). Others understand indigenous guides and information sources as “intermediaries,” who “often possessed far more power than explorers were prepared to admit, since it undermined their own reputations” (Kennedy 2013:162-63). Livingstone, on these readings, continues as the face of colonial power, regardless of whether that is undermined or reinforced.

In the 1870 Field Diary, a complex picture of intercultural relations surfaces. For instance, within Bambarre, Livingstone encounters a diverse mixture of Africans, Arab, and Indian populations. These populations divide not only along ethnic and geographic lines and but also between slaves and free men – a division that begins to complicate the “asymmetrical relations” cited above. In addition, the immobilized Livingstone makes a sustained attempt to acquire geographical information from non-Western informants. Finally, he faces a lack of supplies and a mutinying group of attendants, factors that complicate his geographical mission. These complications, alone and in combination, all circumscribe Livingstone’s lived and discursive authority as well as his work as a geographer. The complications also influence Livingstone’s strategies as a diarist and collector of information.

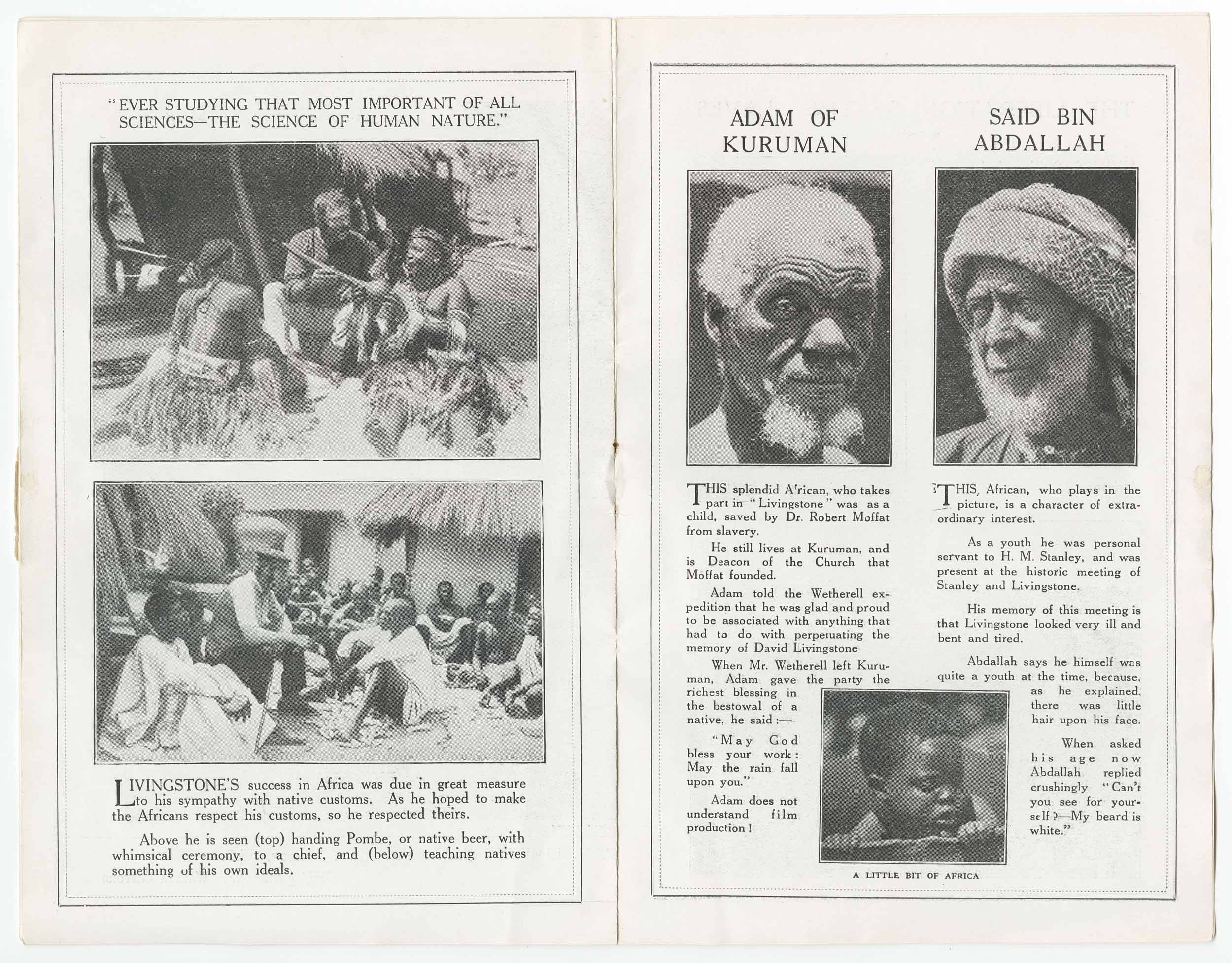

A two-page spread from a promotional booklet for Livingstone: A Drama of Reality (Film), 1925. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. This booklet documents twentieth-century curiosity about Livingstone's informants and guides, while still heroicizing Livingstone, imperial exploration, and Christian conversion.

This essay proposes that we investigate the 1870 Field Diary as a record of information gathered from multiple, overlapping and competing sources, even though the diary (and other records of like it) have typically been read as a single source, first-hand account of European travel in Africa. The essay also argues that in his diary Livingstone conceives of his non-Western interlocutors as separate, lesser entities – individuals not on par with classical authorities such as Ptolemy and Herodotus.

On this reading, the 1870 Field Diary emerges as a palimpsest of diverse information economies or discursive and material strategies Livingstone employs to negotiate trade-offs in money, goods, and prestige as he gathers geographic knowledge. Rather than an instantiated example of an imperial correspondence model that links the metropole with “other, similar interests elsewhere in the colonial ‘peripheries,’” the 1870 Field Diary encodes the network of competing interests at the colonial site (Lester 2001:7-8). In short, Livingstone’s diary acts as a record of intersecting cultural interests and at once encodes European authority and the many moments where that authority stumbles.

Conflicting Loyalties Top ⤴

Livingstone directs the narrative of the 1870 Field Diary towards European knowledge production and writes to a European audience through his descriptions of African geography and culture as well as in his ruminations on life as an explorer. In doing so, he distinguishes himself as a “real” rather than a “theoretical” explorer and evaluates the contributions of other explorers to scientific discourse in relation to his own goals (Livingstone 1870c:II). In this approach, the non-Western populations whom Livingstone encounters and with whom he converses do not qualify as explorers at all, regardless of the information they transmit. This move isolates him from the populations that surround him.

Yet in the narrative of the 1870 Field Diary, Livingstone also finds himself more imbricated in his local circumstances than ever before. He also comes to depend on others for much of the information he records in his diary during this time, thanks to the ulcers that have immobolized him. Sometimes such dependence is implicit. When Livingstone uses the passive voice in his diary, the source of information can be difficult to discern (1870j:LXVII). At other times, the dependance on others is explicit. For instance, in August 1870, Muhamad Bogharib, an Arab trader, sends his men on an expedition at Livingstone’s behest. In exchange for “two thousands [sic] Rupees & a gun,” Muhamad’s men explore the surrounding area and report back that there is not much of interest (Livingstone 1870b:[32]). In this way, Livingstone appears to lend to the information gathered from non-Western informants the same credibility as he does to his own first-hand observations.

| Royal Geographical Society silver medal (front and back), awarded retrospectively to each of the Africans who carried David Livingstone's body to the East Coast of Africa. Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Object images used by permission. May not be reproduced without the express written consent of the National Trust for Scotland, on behalf of the Scottish National Memorial to David Livingstone Trust. Images of the objects from the David Livingstone Centre are copyright Roddy Simpson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. This particular medal is inscribed on its side as follows: "Ulemengo - faithful to the end." |

In other words, circumstances compel Livingstone to cede some amount of his geographical authority. With this, we find Livingstone’s authority failing in other realms as well, perhaps because he cannot rely on movement, discovery, and further exploration to solidify his position. When the Nassickers (a group of nine men recruited for Livingstone’s journey from a government-run school for freed slaves in Nashik, India) refuse to explore on his behalf, Livingstone details the erosion of his lived authority: “I am powerless as they have left me and think that they may do as they like [...]” (1870b:[57]). This erosion occurs in part because because of the Nassickers’ sexual practices with local women: “the head Arabs told me that [the Nassick men] were in the habit of going to the [Manyema] women whose husbands were away and getting food and spending the night with them” (1870b:[14]). Livingstone here navigates a complicated overlay of conflicting loyalties: the Nassickers’ questionable loyalty to him, their behavior toward local women, and the disruption to the local population’s domestic and sexual norms caused by the outsiders.

The Arab traders in Bambarre extend this process. Livingstone refuses to “punish as the Arabs do,” on moral grounds, and the result is that he fears his men see him as weak (1870b:[20]). In response, Livingstone shores up his own moral authority, as when he records the esteem with which local African populations approach him: “They have found out that I am not a slaver and when the people remain stand calling as I pass – ‘This is the good one. ‘Bolongo.’ Friendship Friendship’” (1870e:XIII). Yet, for all that Livingstone condemns Arab discipline, he also depends on the Arab traders for friendship, to provide him supplies, and, ultimately, to facilitate his travels, which only complicates the situation further.

Local Source, Global Knowledge Top ⤴

Because Livingstone finds himself at the intersection (and sometimes the mercy of) these multicultural forces, his lived authority falters and this failing extends to his discursive authority. The 1870 Field Diary reveals traces both of Livingstone’s powerlesness and the changed information economy in which he operates. The European center has become irrelevant, replaced by cultural heterogeneity, and the diary emerges as a repository of multiple narrative accounts and structures of authority. Livingstone’s apparent geographical isolation causes a kind of being in the world most evident when he records overlapping sources of information. This information diaspora is, of course, still mediated through Livingstone and his European (primarily British) framework, but tracing its existence reveals the multiple vectors that ultimately shape European knowledge production.

Livingstone’s geographical observations perhaps best capture this process, specifically its inherent unruliness, Livingstone’s attempts to corral it, and his own blind spots. When Livingstone notes, “I have to go down the central Lualaba or Webb’s lake river – Then up the Western or Young[‘]s lake river to Katanga head waters & then retire – I pray that it may be to my native home” (1870h:XVIII), he overlays and interchanges British names which he himself has imposed on local African geographical features (Webb’s lake river, Young’s lake river) with the local names (Lualaba, Katanga).

![A page of the 1870 Field Diary in natural light (Livingstone 1870f:[XIV v.2]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). A page of the 1870 Field Diary in natural light (Livingstone 1870f:[XIV v.2]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/livingstones-global-sources/liv_000203_0002_color-article-1200.jpg)

A page of the 1870 Field Diary in natural light (Livingstone 1870f:[XIV v.2]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The map charts the rivers crossed by Ramadan and Hassani, two Arab traders, in August and September 1870. In other words, the layout of the map is based wholly on geographical details collected from Livingstone's informants.

This interweaving suggests that he cannot – even for his intended British audience – simply use the new names, unless they are paired with local names. In other words, his wish to leave Africa and return to, ironically, his “native home” (Livingstone 1870h:XVIII) – where the names are singular – underscores the extent to which he is juggling multiple lived and discursive frameworks while in Bambarre. Livingstone may attempt to frame himself as a European writing to his “home reader,” but the information diaspora in which he operates erodes the self-other boundary on which that frame depends.

Ultimately, Livingstone’s limitation lies in believing himself much less in the world than he really is. In “long[ing] excessively to be away” (1870i:XXVIII), he fails to understand that such an escape is not possible. His work actually depends upon recourse to and immersion in a variety of information sources, from his own first-hand observations, to classical authorities such as Ptolemy and Herodotus, to the diverse populations he encounters in Bambarre. It is not just a matter of inscribing his name in classical or contemporary British geographical conversations.

Conclusion Top ⤴

Livingstone’s journey to Africa might seem focused on reaching the distant source(s) of the Nile, so that he can deliver this information to Europe in order to reconfirm his standing as one of the leading British explorers of the day. However, the 1870 Field Diary reveals that the journey to those sources depends on sources of another kind: non-Western informants. Attention to these latter sources in a critical reading of the diary, in turn, illuminates the rich cultural confluence from which seemingly single-authored imperial texts might sometimes emerge.

Works Cited Top ⤴

[View the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project's full bibliography.]

Barnett, Clive. 1998. “Impure and Worldly Geography: The Africanist Discourse of the Royal Geographical Society, 1831-73.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 23 (2): 239-251.

Bridges, Roy C. 1998. “Explorers’ Texts and the Problem of Reactions by Non-Literate Peoples: Some Nineteenth-Century East African Examples.” Studies in Travel Writing 2 (Spr. 1998): 65-84.

Jeal, Tim. 2013. Livingstone: Revised and Expanded Edition. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1973.

Johnston, Anna. 2013. “'Greater Britain': Late Imperial Travel Writing and the Settler Colonies.” Where All Things Are Possible: Oceania, the East and the Victorian Imagination. Edited by Richard Fulton and Peter H. Hoffenberg. Farnham: Ashgate: 31-43.

Kennedy, Dane. 2013. The Last Blank Spaces: Exploring Africa and Australia. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Lester, Alan. 2001. Imperial Networks: Creating Identities in Nineteenth-Century South Africa and Britain. London: Routledge.

Livingstone, Justin D. 2014. Livingstone’s “Lives”: A Metabiography of a Victorian Icon. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Pratt, Mary Louise. 1992. Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation. London: Routledge.

Spurr, David. 1993. The Rhetoric of Empire: Colonial Discourse in Journalism, Travel Writing, and Imperial Administration. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

![Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_013723_0001-new-carousel_0.jpg)

![Processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's "Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal" (Livingstone 1870a:[3] pseudo_v4_BY), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's "Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal" (Livingstone 1870a:[3] pseudo_v4_BY), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000211_0003_pseudoBY_940_by_592-carousel.jpg)

![David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, [1869], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland: CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, [1869], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland: CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_003006_0001-new-carousel_0.jpg)