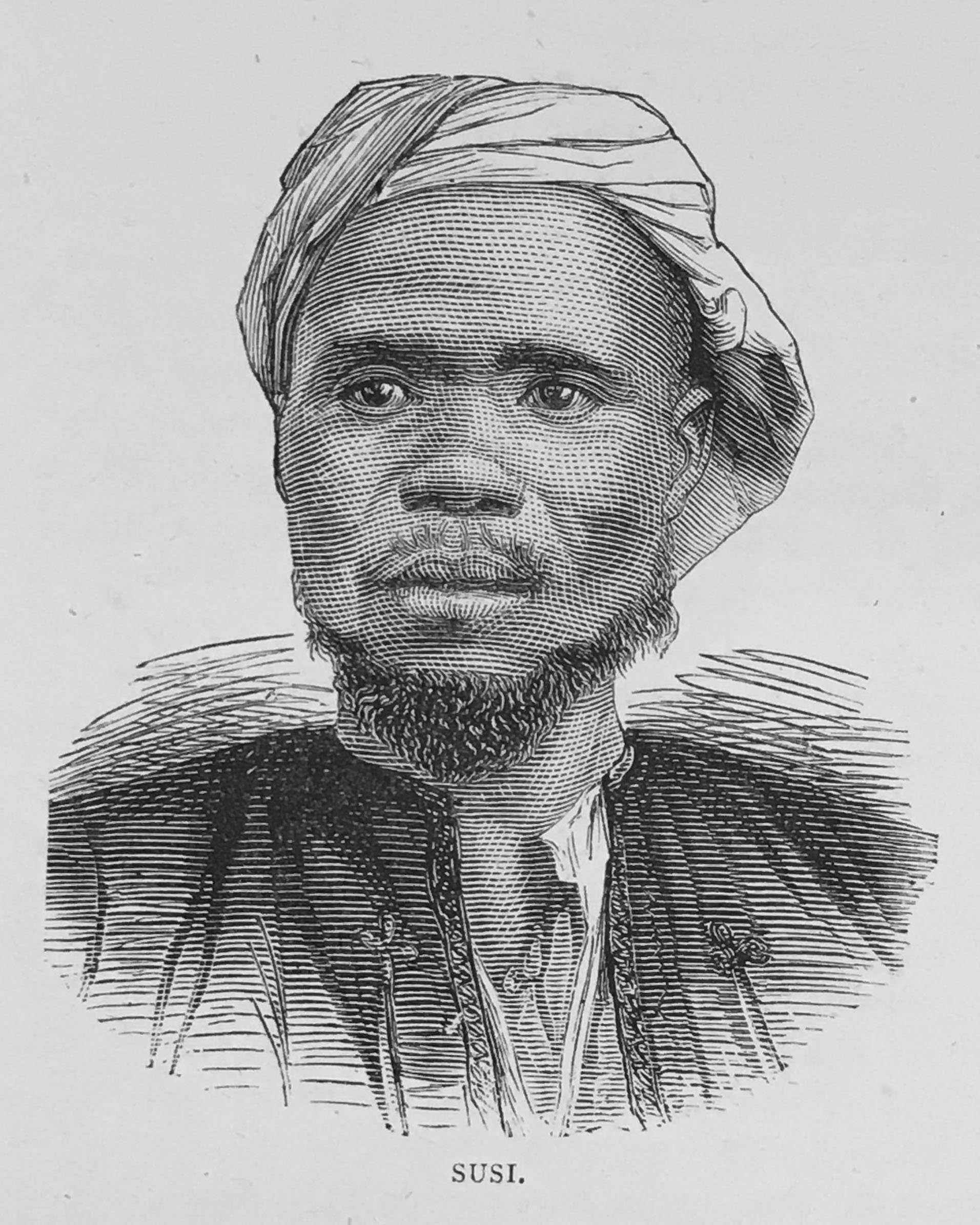

Livingstone, Central Africa, 1870

Cite page (MLA): Wisnicki, Adrian S., and Megan Ward. "Livingstone, Central Africa, 1870." Justin D. Livingstone, ed. In Livingstone's 1870 Field Diary. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. University of Maryland Libraries, 2017. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/8903fa5b-7919-4f98-96ad-9b147e7f16d2.

This essay shifts critical focus from biographical approaches centering on Livingstone in 1870 to the central African cultural material found in the 1870 Field Diary. In doing so, the essay argues that the diary’s innovative narrative style documents and, at times, foregrounds a regional universe whose complexity stands at odds with the reductive characterizations later imposed upon it by Livingstone and others.

Livingstone Top ⤴

In July 1869, David Livingstone left the village of Ujiji on the eastern shore of Lake Tanganyika and set out west to explore what he incorrectly believed to be the western line of drainage of the Nile River. To make the journey, Livingstone traveled with Arab traders and their followers. His course took him into the eastern part of the present day Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the region of Manyema (now Maniema).

The party reached Bambarre, a small Congolese village and base of Arab trading activity, on 21 September 1869. From here, Livingstone expected to carry on westward to the Lualaba and Lomami Rivers, which he hoped would prove to be two of the main branches of the Nile (Livingstone 1870h:XVIII, 1870i:XLI). Instead, despite two sustained attempts to leave the village over the next year, circumstances compelled Livingstone to stay in Bambarre until 16 February 1871.

![David Livingstone, Annotations on Map from John H. Speke, Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile (1863), [1869-73]:[1], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/). As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). David Livingstone, Annotations on Map from John H. Speke, Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile (1863), [1869-73]:[1], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/). As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/livingstone-central-africa-1870/liv_003181_0001-detail-article.jpg)

David Livingstone, Annotations on Map from John H. Speke, Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile (Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons, 1863), [1869-73]:[1], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. Livingstone has modified and annotated the printed map based on data from informants. The relative lack of detail in the "Manyemaland," which lies just west of Lake Tanganyika, suggests that Livingstone added the annotations before actually visiting the region.

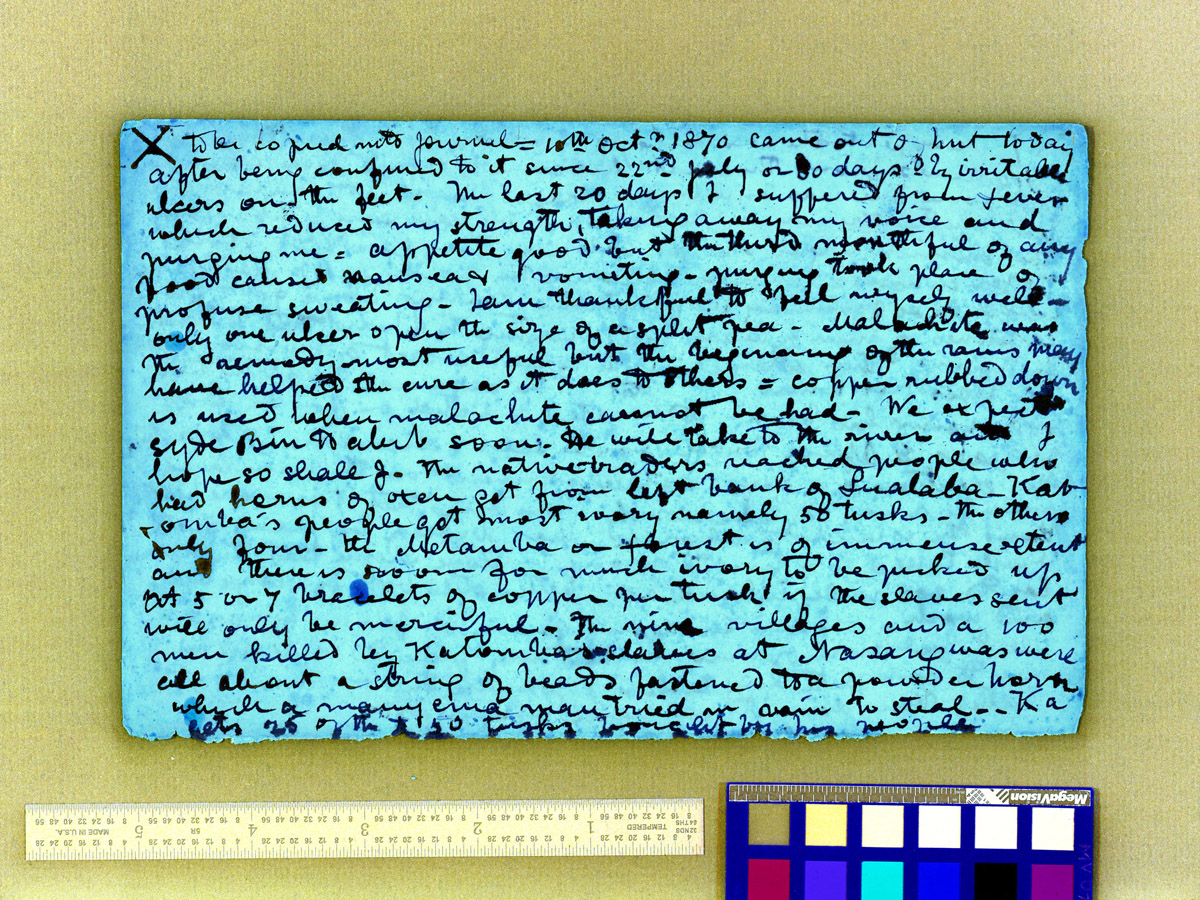

The delay proved to be one of the longest and most frustrating of his career or, as he puts it in his 1870 Field Diary, “the sorest delay I ever had” (1870j:LXIX). The nadir came when Livingstone developed flesh-eating ulcers on his feet and was forced to remain in his hut in Bambarre for 80 days, the last 20 of which he suffered from acute fever, nausea, and vomiting (1870e:X).

The delay wholly upended Livingstone’s ambitions as a Victorian explorer who had to keep moving in the interests of gathering geographical information. Instead, Livingstone’s world narrowed to the village of Bambarre and to its inhabitants. These included local Africans, Arab traders from east Africa, the Arabs’ African followers, Livingstone’s few attendants, and the Nassickers, a set of nine attendants from a government-run school for freed slaves in Nashik, India.

Scholars Top ⤴

Ultimately, the delay led Livingstone to record his observations in the 1870 Field Diary at a level of detail and depth unseen since his famous first sojourn in southern Africa (1841-56). Previous scholarship has given little if any attention to this point and has on the whole focused instead on Livingstone’s immobility, the lack of external events in his life during the period, and his apparent mental deterioration.

Reginald Coupland, for instance, notes that “week after week, Livingstone sat idle at Bambarré […] What could he do? […] There was little to record in the journal. He could only read,” etc. Livingstone, Coupland adds, was “depressed,” plagued by “interminable delay,” and subject to “utter loneliness, and longing for home” (1945:83, 90). Tim Jeal enumerates the many impediments Livingstone faced at this time and underscores how Livingstone’s decision to confront these “demonstrates the almost superhuman determination of the greatest explorers never to surrender” (2011:253).

A processed spectral image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871e:X spectral_ratio). Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. A page of the diary that Livingstone opens by discussing his recent illnesses and immobility.

Elsewhere, Jeal also devotes a whole chapter of his biography to Livingstone’s “Fantasy in Manyuema” (1973:322ff.) and details Livingstone’s theories of the central African watershed. Oliver Ransford takes this approach further by focusing on Livingstone’s “cyclothymic personality” and by discussing how in the final seven months in Bambarre (22 July 1870-16 Feb. 1871), Livingstone “escaped from the reality of loneliness and discouragement into the realms of imagination and visionary transcendentalism” (1978:264, 262).

A long critical tradition focuses on Livingstone’s state of mind and his activities during the period (for other examples of this approach see, e.g., Campbell 1929, Seaver 1957, Northcott 1973, Listowel 1974, Buxton 2001, Tomkins 2013, and Bayly 2014). The emphasis has prevented both critics and biographers from conceptualizing Livingstone’s immediate context – nineteenth-century central Africa – as a complex place teeming with cultures, individuals, and forces that far exceeded Livingstone’s activities and that certainly did not center on him.

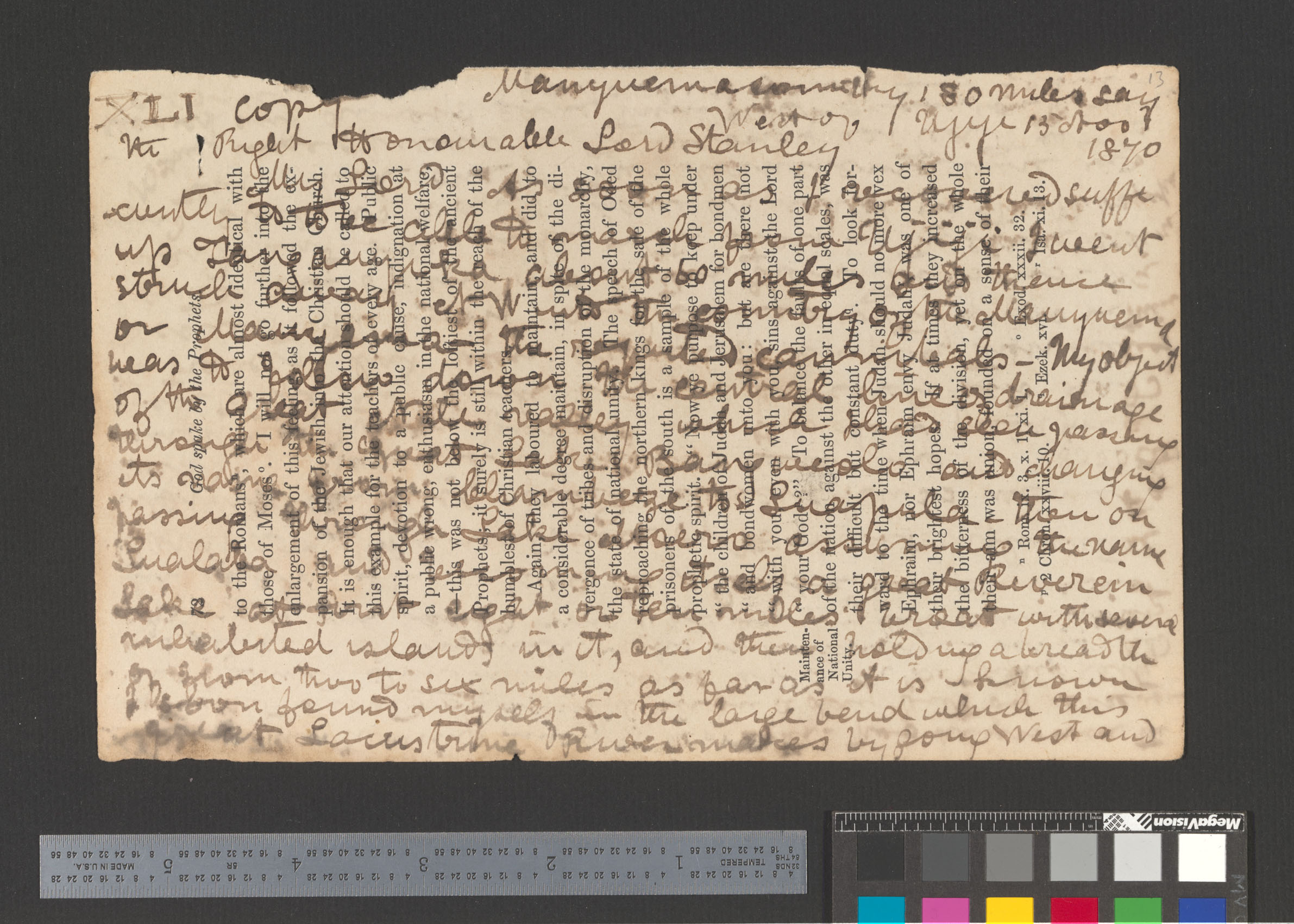

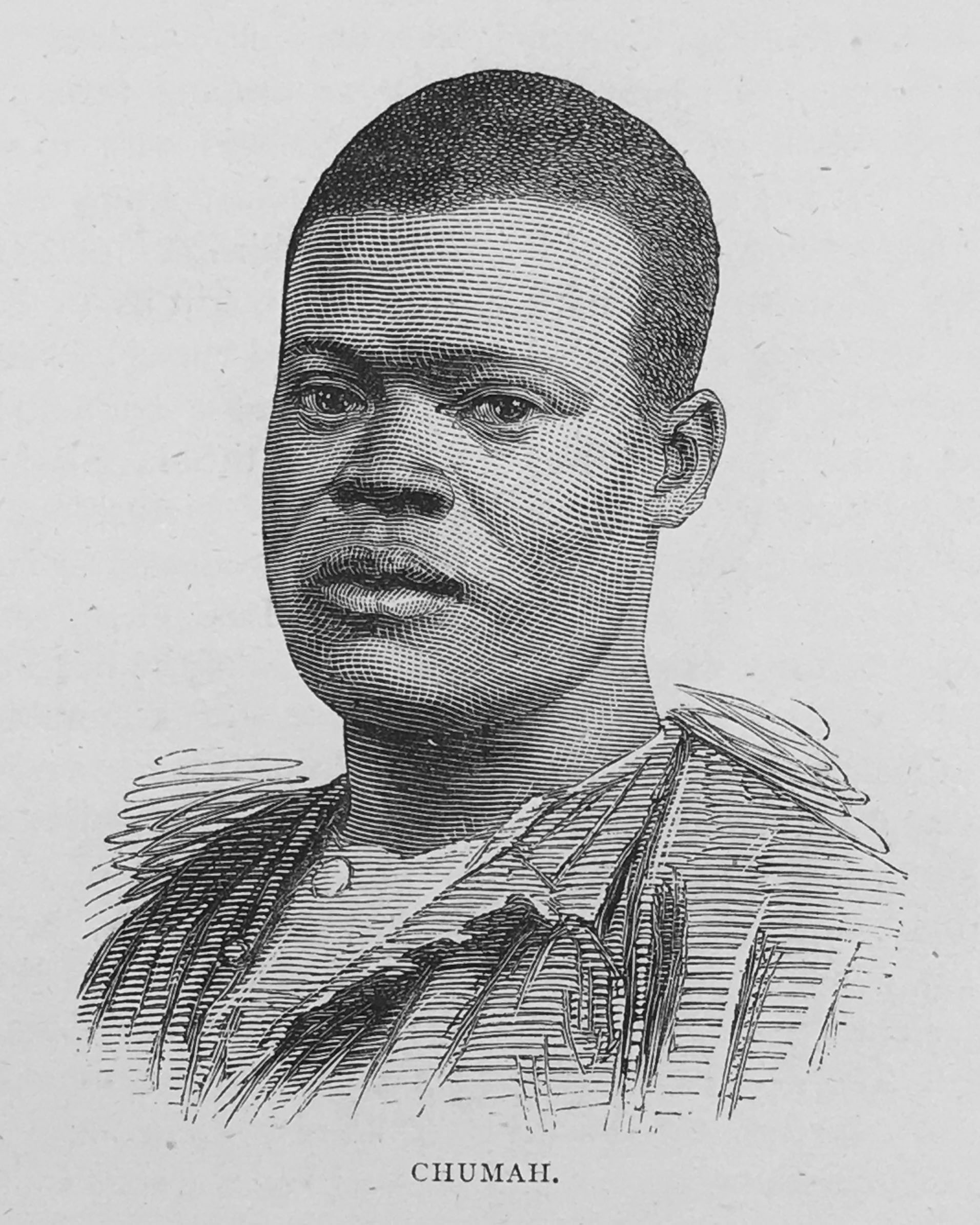

| (Left; top in mobile) Chumah and (right; bottom) Susi. Illustrations from James E. Ritchie, The Pictorial Edition of the Life and Discoveries of David Livingstone, 2 vols (London and Edinburgh: A. Fullarton & Co., 1876-1879), 2:65. Copyright Adrian S. Wisnicki. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. These illustrations of Chumah and Susi resemble photos of the two men taken in England after Livingstone's death. |

The issue, particularly in terms of locally-based central African actors, extends to important historical scholarship (e.g., Bennett 1986:113-14). Even some landmark studies on the role of African populations in exploration focus only on the porters, interpreters, and guides that assisted travelers like Livingstone (e.g., Simpson 1976) or on the most famous “intermediaries” that specifically worked with Livingstone: Chuma, Wekotani, Susi, and Wainwright (Helly 1987; Kennedy 2013:170ff., also 159-94; cf. Bridges 1987:191; also see Pettitt 2007).

Revising Manuscripts Top ⤴

In these ways, critical approaches on the whole tend to follow Livingstone’s own lead. In rewriting and revising the 1870 Field Diary to create the corresponding segment of the Unyanyembe Journal (1866-72), Livingstone compressed the bulk of the diary – and all the rich local cultural detail contained therein – to a few longer passages spanning just over three pages in the journal. Concurrently, he expanded the diary’s last segment to focus on his travels between Bambarre (dep. 15 Feb. 1871) and Nyangwe (arr. 23 Mar. 1871). Such narrative inversion gives a good indication of what Livingstone thought was worth keeping and what he believed could be discarded – values in keeping with the mobility required of a Victorian explorer.

Such editorial practices continued when Livingstone’s friend and editor Horace Waller created the posthumously-published Last Journals (Livingstone 1874). Waller combined the 1870 Field Diary and Unyanyembe Journal to create a hybrid record, one that would be most complete as it joined the longest parts of each text. From there, Waller and others took the original texts through a massive process of revision (Helly 1987).

Frontispiece and title page from the Last Journals (Livingstone 1874,1). Courtesy of the Internet Archive.

In discussing this period of Livingstone’s life and, as relevant, the broader central African history it encompasses, literary critics, biographers, historians, and others have for the most part worked with the Last Journals as their primary text, with the occasional reference to published versions of letters or other archival sources (e.g., Coupland 1945, Seaver 1957, Jeal 1973, Ross 2002, Bayly 2014). Unlike the 1871 Field Diary, the 1870 Field Diary can in large part be read with the naked eye, but it has received little if any attention.

In neglecting this source and others like it, such scholarship runs counter to a trend in travel writing scholarship that has been gaining in momentum since the 1970s and 80s, following on the pioneering work of historian Roy C. Bridges (1973, 1977, 1987). Bridges advocates for returning to the original field notes and similar sources of travelers like Livingstone. Bridges argues that such unabridged sources need to be read alongside revised and/or published materials in order to develop the most comprehensive understanding of encounters in the field.

![David Livingstone, Annotations on Map from John H. Speke, Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile (1863), [1869-73]:[2], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/). As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). David Livingstone, Annotations on Map from John H. Speke, Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile (1863), [1869-73]:[2], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/). As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/livingstone-central-africa-1870/liv_003181_0002-detail-article.jpg)

David Livingstone, Annotations on Map from John H. Speke, Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile (Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons, 1863), [1869-73]:[2], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. Livingstone never visited the majority of areas depicted in this map – one of his most detailed of this part of south central Africa – but rather drew on conversations with Arab and African travelers.

The approach has gained traction not only in terms of more traditional “analogue” research, such as Dane Kennedy’s recent work (e.g., 2013) or the lavishly illustrated volume on explorers’ sketchbooks (Lewis-Jones and Herbert 2016), but also in the digital humanities via such projects as Olive Schreiner Letters Online, Livingstone Online, and, of course, the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project. Each of these digital projects, in fact, focuses on providing access to a range of unrevised and revised archival document types produced by Victorian visitors to Africa.

In some of his foundational pieces, Bridges outlines the revisionary stages through which such materials passed and discusses the complexities in differentiating among those stages (see, especially, 1977:3-4). He also highlights the heterogeneous nature of the contents of the earliest stage manuscripts and suggests that these contain the most direct information from informants, “what the explorer heard” (1987:181, italics in original). Of such original records, Bridges indicates, “Livingstone’s notebooks are the most important example” (1987:181).

![An image of a page from Livingstone's Notebook III (22 July-7 Oct. 1871:[2]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Images of the Livingstone manuscripts from the David Livingstone Centre are copyright University of Glasgow Photographic Unit. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page from Livingstone's Notebook III (22 July-7 Oct. 1871:[2]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Images of the Livingstone manuscripts from the David Livingstone Centre are copyright University of Glasgow Photographic Unit. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/livingstone-central-africa-1870/liv_000022_0002-article.jpg)

An image of a page from Livingstone's Notebook III (22 July-7 Oct. 1871:[2]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Images of the Livingstone manuscripts from the David Livingstone Centre are copyright University of Glasgow Photographic Unit. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. Livingstone here discusses observations he made while collecting vocabulary from Zanzibari and central African informants.

Bridges' emphasis on the priority of original records has sparked a debate in travel writing studies. Some critics, such as Tim Youngs (1994:6-7), have suggested that all travel records, whatever their stage of production, work mainly to reinscribe British imperial ideologies. Yet Bridges (1998:69 and passim) has countered by arguing “that it is possible to get behind the form of the discourse to some sort of representation of objective realities about Africa and Africans,” if one acknowledges the limitations of working with one-sided, primarily British historical records and, to compensate, takes a cross-cultural, interdisciplinary approach. (For a concise summary of the opposing arguments, see Wisnicki 2010:2.)

The current edition and the present essay extend the critical trend initiated by Bridges by returning to the original, unabridged text of the 1870 Field Diary, while remaining mindful of the challenges and limitations inherent in working with such a source text. In doing so, we demonstrate the value of this text (and others like it) in complicating and diversifying critical understanding of nineteenth-century intercultural encounters in the field and the historical realities of non-western populations cited in such texts.

The 1870 Field Diary Top ⤴

In the 1870 Field Diary, we find that Livingstone’s personal story of travel – the type of content that he and subsequent scholars have most valued – stands alongside many, many other (often neglected) stories and historical materials related to nineteenth-century life in central Africa.

This latter content makes the 1870 Field Diary a unique historical document. To create this document, Livingstone invented a medial narrative style that doesn’t quite map onto Bridges’ three stages of production (Bridges 1987:180-90; for more on this, see Livingstone’s Composition Practices). The style, as we note elsewhere, oscillates between a field diary and a journal – at least as Livingstone normally crafted such documents – and so enables Livingstone to capture the immediacy of his experiences with a reflective depth not seen in other diaries of the period.

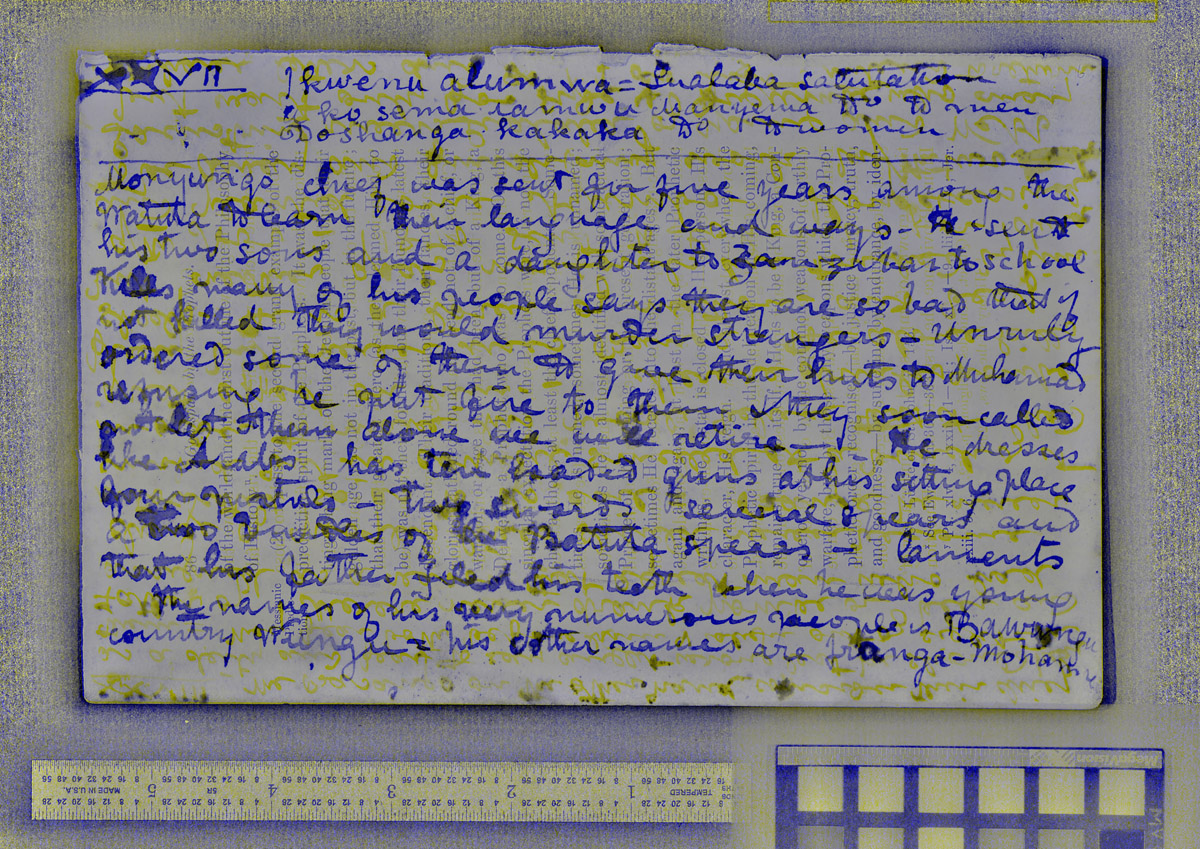

A processed spectral image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871i:XXVII pseudo_v4_BY). Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. Livingstone begins this undated page by recording a few phrases from a local African language, then focuses the rest of the page on information related to Monyungo, a local African chief. There are no direct or oblique references to Livingstone's personal thoughts or experiences.

The record also does not focus on developing events in Livingstone’s own life because he is immobilized; he doesn’t leave Bambarre till the very end of the 1870 Field Diary. Rather, the 1870 Field Diary captures local and regional information by layering Livingstone’s reflections on Biblical, historical and contemporary European events onto narratives of local central African events and recorded stories. Livingstone cycles through topics such as ancient geographical knowledge, contemporary debates in Britain on the production of science, disputes among African villagers, words collected from African vocabularies, botanical or zoological observations, and much more.

With such an approach, the diary ultimately documents the many contexts for the encroachment of Arab traders into the Congo at this historical moment. It outlines step-by-step the impact of such encroachment on local populations and their social relations. It details complex regional dynamics and the circulation of geographical, medical, agricultural, and other such information among an array of African and Arab individuals.

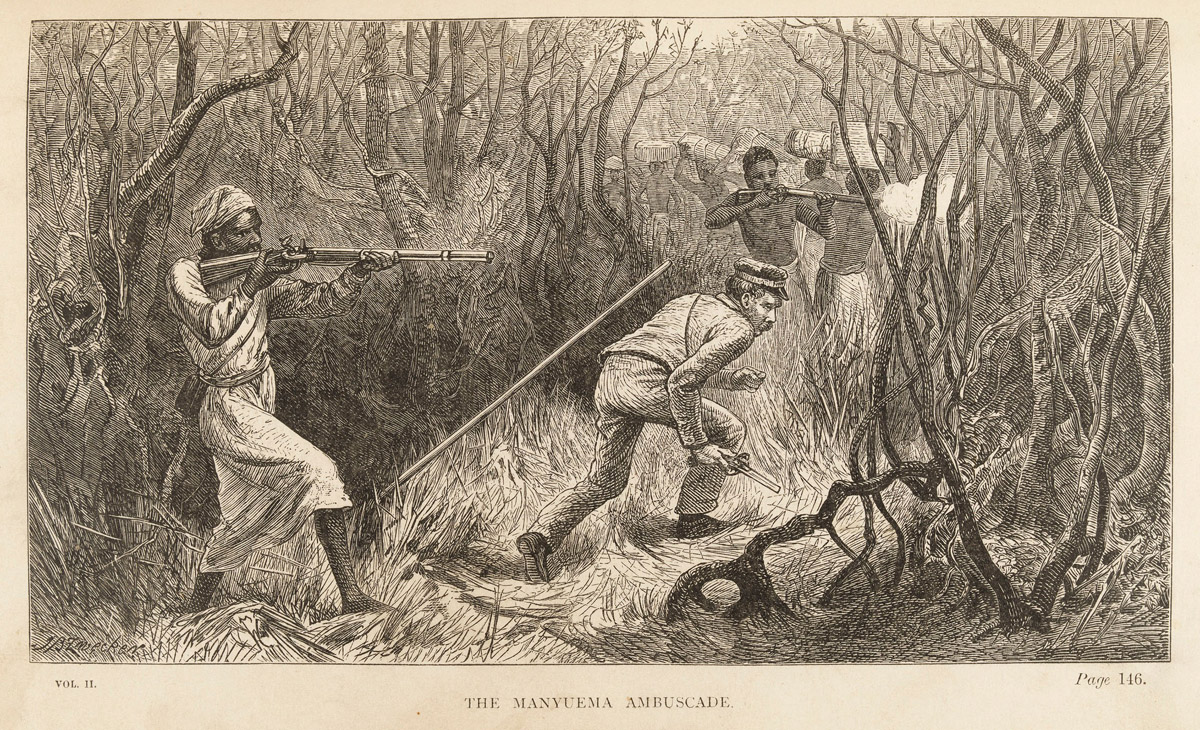

The Manyuema Ambuscade. Illustration from the Last Journals (Livingstone 1874,2:opposite 146). Courtesy of Edinburgh University Library. This image presents the illustrator's impression of an event that Livingstone records in his diaries; it correlates with information in Livingstone's writings in that it presents everyone – Arabs, Africans, and Livingstone himself – as armed with guns.

Finally, the diary presents local and regional African populations not just as passive victims of violence, but as evolving individuals that shift from gullibility, to suspicion, and, finally, to complex strategies of resistance in their interactions with the Arab traders. The diary thus makes a breakthrough – overlooked till now – in the representation of such African populations by travelers and explorers like Livingstone.

Zanzibar Trade in Central Africa Top ⤴

This critical oversight has occurred, in part, because of sustained focus on Livingstone himself, a trend that stretches back to Henry M. Stanley’s writings (1872, etc.) and earlier. As some have observed, Livingstone became the subject of a “biographical industry” that developed from the late nineteenth-century to the mid twentieth-century (MacKenzie 1996:203; cf. Livingstone 2015). Such focus has prevented critics from giving adequate attention to the fact that late nineteenth-century travel in east and central Africa placed explorers like Livingstone squarely in the middle of Zanzibar’s evolving African empire – a position we see uniquely captured in the 1870 diary, thanks to the unusually long time Livingstone spends in one place.

This empire, which reached its height during the tenure of Sultan Barghash bin Said (r.1870-1888), exerted direct or indirect influence over a vast portion of the continent and “was aggressively expansionist in its ambitions” (Kennedy 2013:120-21). The workings of the empire compelled European visitors to subsume their ambitions with the broader ambitions of the Zanzibari empire and, often, to “bend to the will” of that empire’s objectives (Kennedy 2013:100, 126).

|

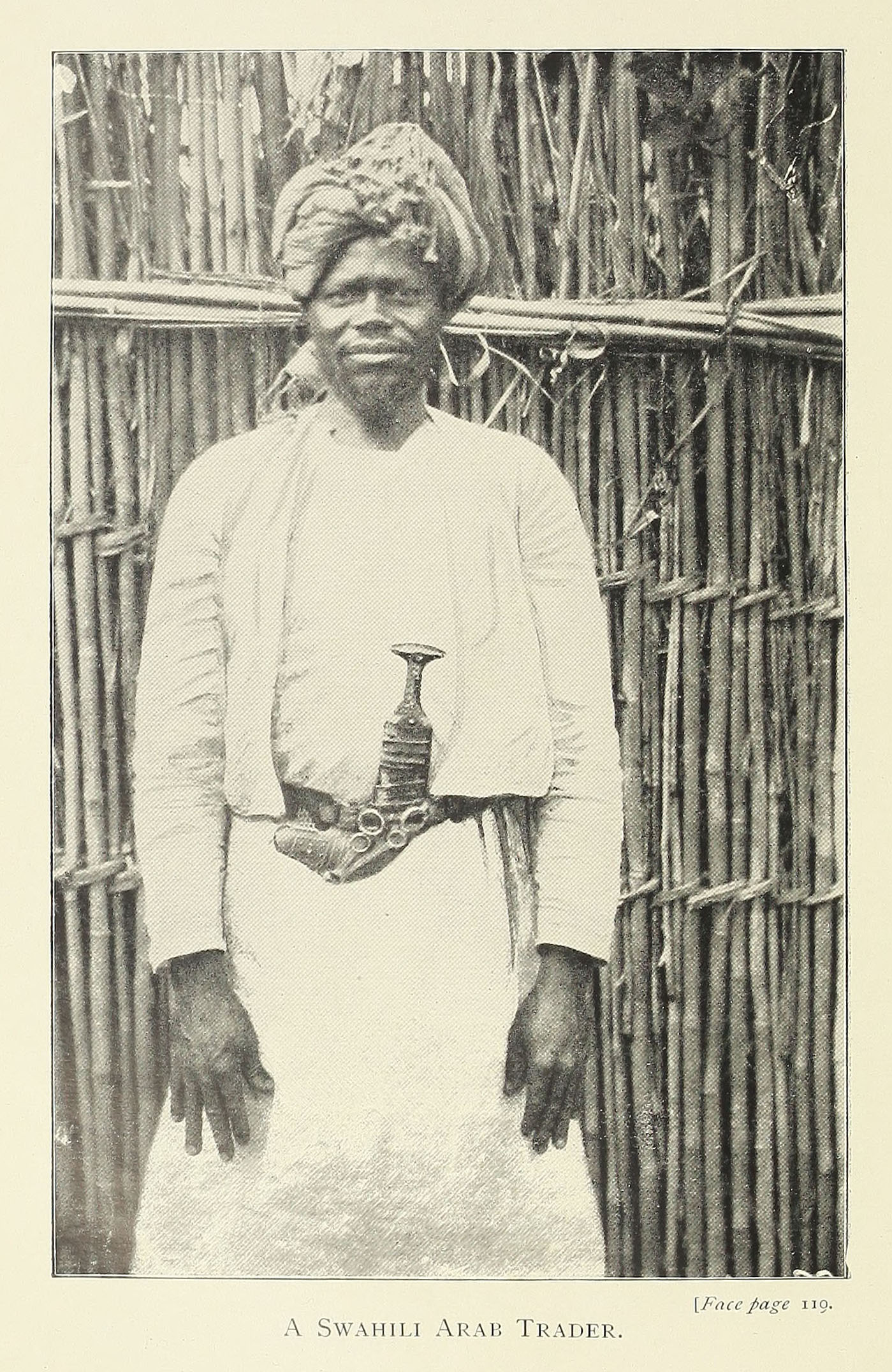

(Left; top in mobile) Sultan of Zanzibar [Barghash bin Said]. Illustration from James E. Ritchie, The Pictorial Edition of the Life and Discoveries of David Livingstone, 2 vols (London and Edinburgh: A. Fullarton & Co., 1876-1879), 2:n.p. Copyright Adrian S. Wisnicki. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. (Right; bottom) A Swahili Arab Trader. Illustration from Harry H. Johnston, The Nile Quest (London: Alton Rivers, Ltd., 1906), opposite 119. Courtesy of the Internet Archive. These illustrations tell us as much about Victorian-era orientalist fantasies as they do about these individuals. |

In the late nineteenth-century, one of the empire’s principal expansionist tendencies focused on finding ivory to satisfy global demand – particularly in the Congo – which, Livingstone noted, was “like gold digging” (1870b:[32], cf. [24]-[33]). The ivory derived both from elephants killed for the purpose and those that had died by natural causes (see Bridges 1988:199, 207-13).

Much of the ivory passed through London to the rest of Europe, but there was also significant demand in the Middle East and in Asia. This ivory served the needs of “an extraordinary range of industrial products and decorative arts” including “billiard balls, knife handles and piano keys” as well as “all manner of lesser uses” (Hyam 2002:217, cf. Livingstone 1874:89-92).

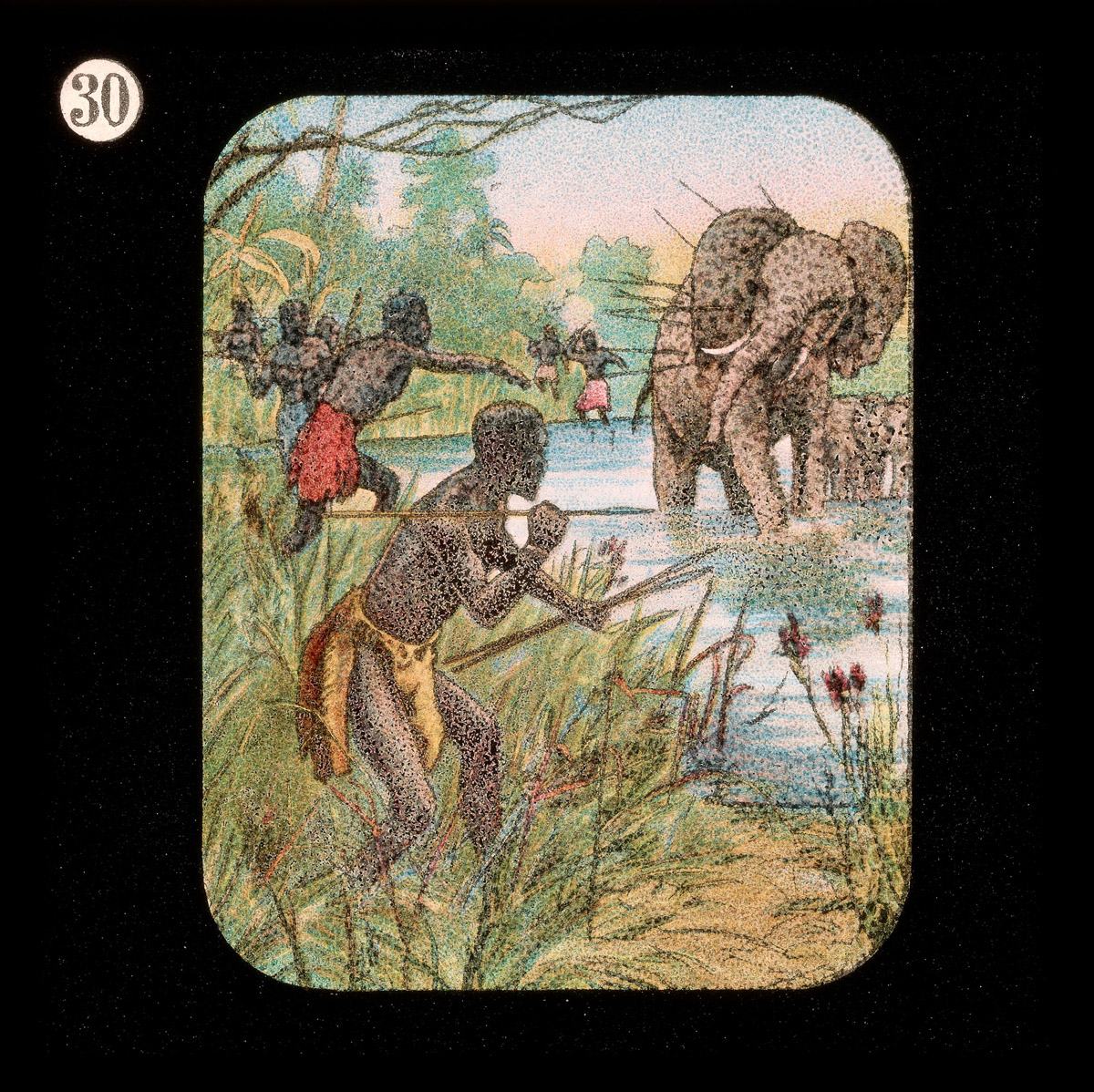

Africans hunting an elephant. Lantern slide from the Life, Adventures, and Work of David Livingstone, date unknown. Courtesy of the Smithsonian Libraries, Washington, D.C.

In the Congo, world ivory demand translated into the arrival of Arab traders in the mid- to late-1860s (including the most famous of such traders Tippu Tip), the widescale introduction of firearms, and the advent of slavery, particularly to supply harems for the Arabs and porters for transporting the ivory (Northrup 1988:27-28, cf. Reid 2012, Macola 2016).

Expansion into the Congo proceeded by the creation of depots and bases, which the Arab traders and their followers then used to launch forays farther afield. The trading parties, often financed by capital from Indian merchants on the east African coast, brought together diverse individuals, including “Omani Arabs, coastal Swahili, inland Africans, and others” (Northrup 1988:23). Despite European characterization, labor in these trading parties took highly differentiated forms.

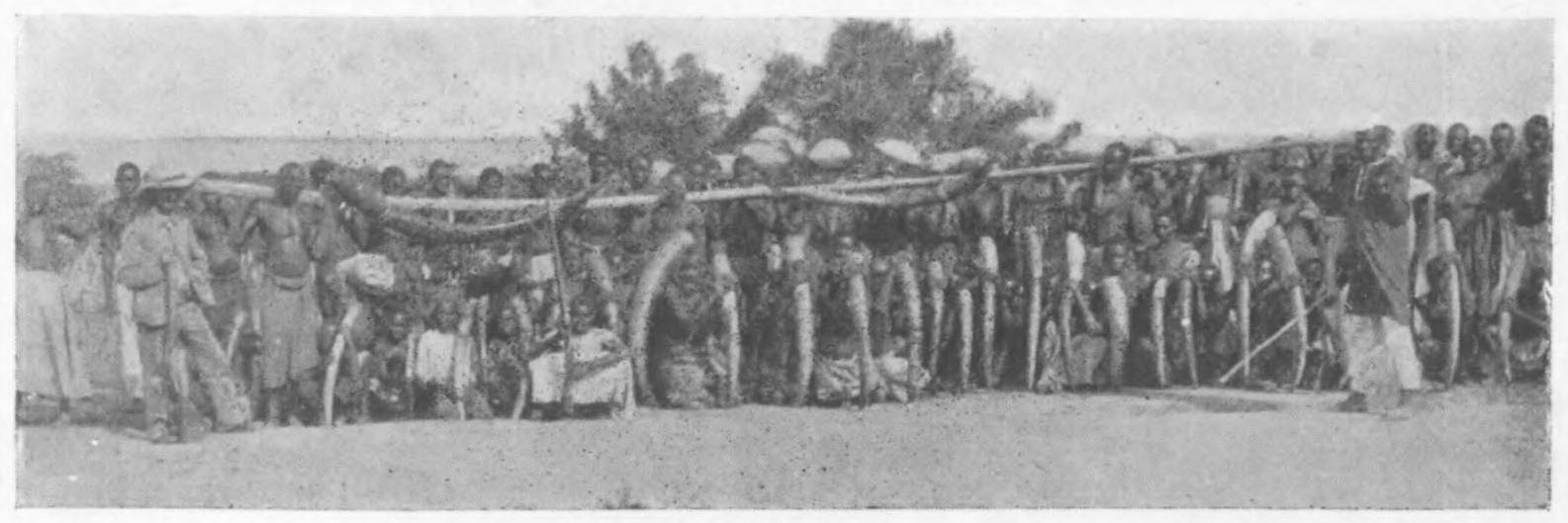

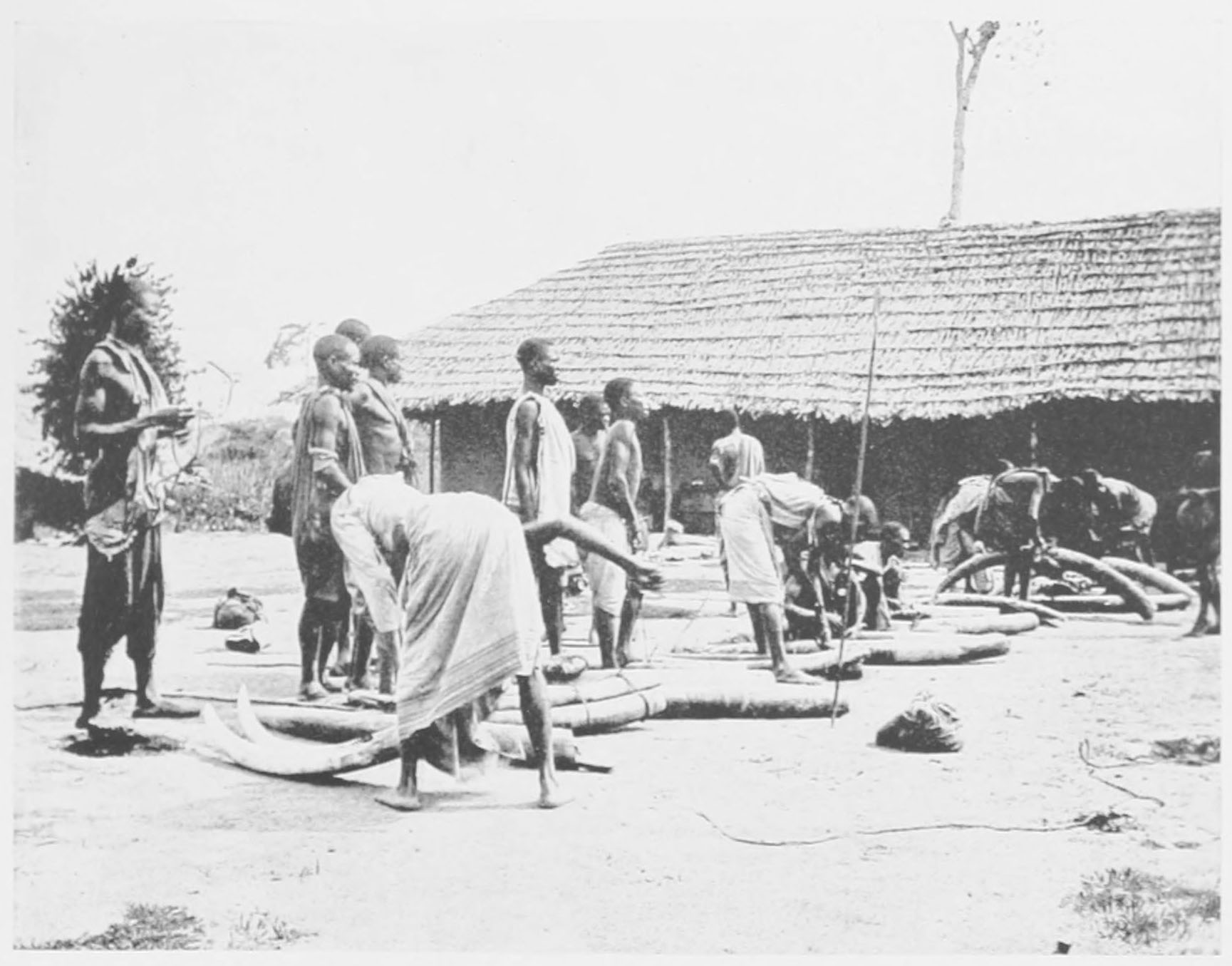

(Top) An Ivory Caravan on the March. Image from Cherry Kearton and James Barnes, Through Central Africa from East to West (London, New York, Toronto, and Melbourne, 1915), opposite 138. (Middle) An Ivory Caravan Arriving at Kotakota. Image from Harry H. Johnston, British Central Africa (London: Methuen & Co., 1897), 178. (Bottom) Ivory Trader's Yard. Image from Cherry Kearton and James Barnes, Through Central Africa from East to West (London, New York, Toronto, and Melbourne, 1915), opposite 138. Courtesy of the Internet Archive. Although these images post-date Livingstone's time and picture activites in different parts of central Africa, the images convey some sense of the on-the-ground realities of the central and east African ivory trade.

In east Africa, the Nyamwezi ethnic group pioneered a sophisticated culture of “wage labor shaped by indigenous precapitalist labor norms, but closely linked to merchant capital and the global economy” (Rockell 2006:6). The use of slaves as porters in the Congo – where other ethnic groups, such as the Bira (in the northeast) and Bisa (in the southeast), had previously dominated trade – constituted a break with east African caravan norms (Livingstone 1870b:[69], Wilson 1972, Rockell 2006:17).

The rush for ivory also compelled the traders “to build up their own infrastructure” and, as Tippu Tip eventually did, to organize a state, one nominally independent, but still loosely aligned with Zanzibar (Sheriff 1987:190, Vansina 1968:238, Renault 1989:161-63). Ujiji, on the eastern shore of Lake Tanganyika, served an important gateway to the emerging central African infrastructure and, indeed, the village was Livingstone’s departure point in 1869 (Bennett 1974:226-28).

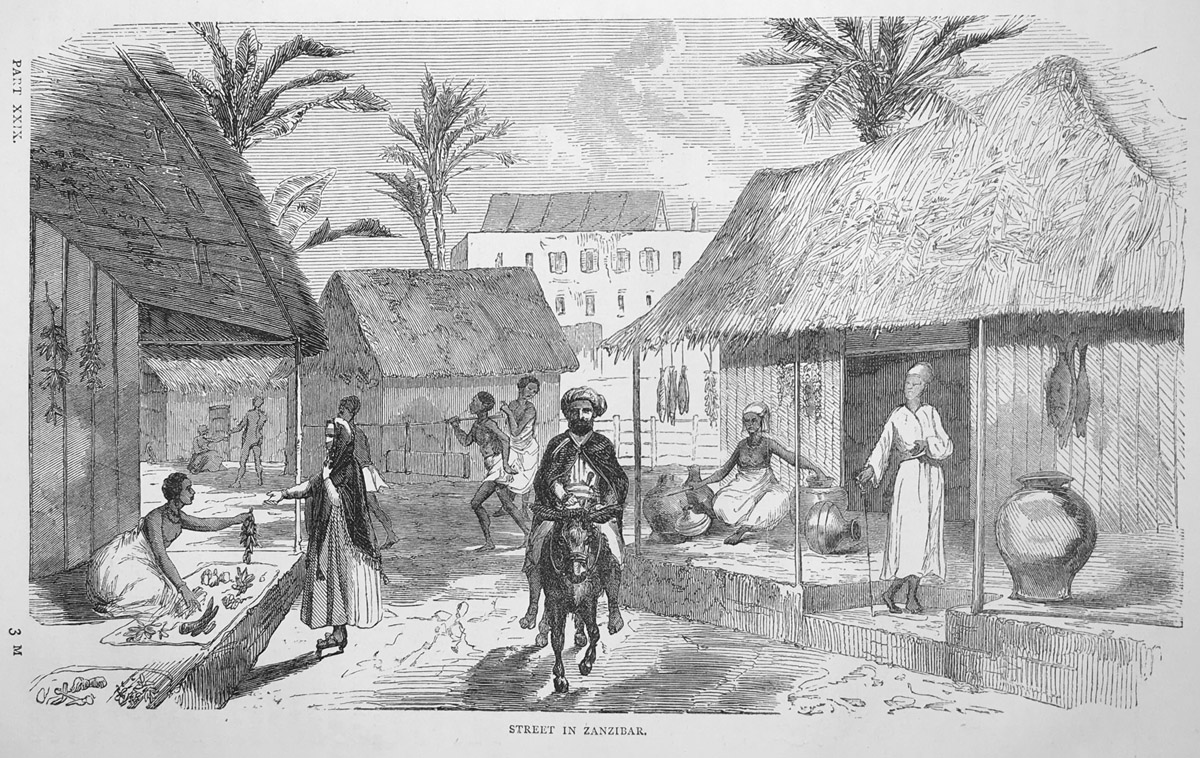

Street in Zanzibar. Illustration from James E. Ritchie, The Pictorial Edition of the Life and Discoveries of David Livingstone, 2 vols (London and Edinburgh: A. Fullarton & Co., 1876-1879), 2:601. Copyright Adrian S. Wisnicki. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The similitude between this illustration and any real street in nineteenth-century Zanzibar is unknown, but the illustration helps foreground the diversity of the island's population. This diversity, and particularly its underlying power dynamics, played a key role in structuring Zanzibar's trading empire.

Livingstone thus developed the 1870 Field Diary in the context of Zanzibari imperial expansion, so forces and events engineered by the expansion shaped his immediate experiences and the content of his writing. Attention to this dynamic allows for a richer critical account of Livingstone’s discursive circumstances and the regional information captured by the diary. Indeed, although critics have long dismissed this period in Livingstone's life as one of stasis or as providing insights only into Livingstone's state of mind, Livingstone's diary, in fact, captures the intricacies – from the ground up – of the evolving intercultural dynamic in central Africa during this time.

Manyema Top ⤴

Likewise, cultural developments in the immediate area of the Congo from which Livingstone wrote – Manyema – also influenced the composition and content of the diary. Livingstone arrived in the area at a moment of upheaval, especially in terms of evolving social relations between Arab traders and local central African populations. Livingstone’s extended stay in Bambarre gave him – the only European in a mix of Arab and African populations – a unique vantage point on these changing social relations.

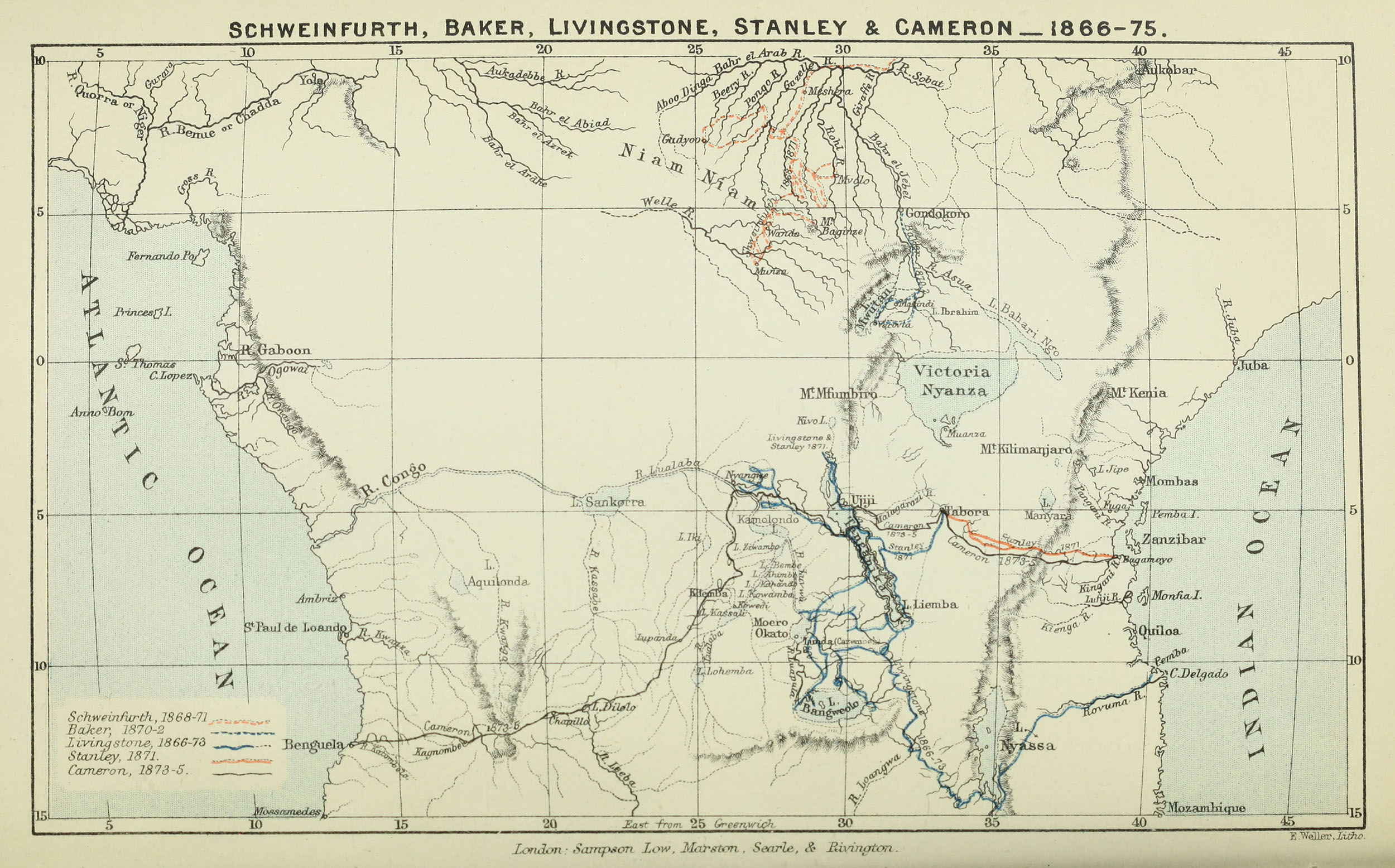

Schweinfurth, Baker, Livingstone, Stanley & Cameron_1866-1875. Map from Through the Dark Continent (Stanley 1878,1:n.p.). Courtesy of the Internet Archive. Beyond charting the travels of the explorers cited, the map's details (or lack thereof) also implicitly track the approximate extent of Zanzibari trader penetration into central Africa at this historical moment, as the explorers usually followed in the footsteps of these traders.

West of Lake Tanganyika, where trade had previously taken a regional form, Arab expansion followed two principal directions. Initially, efforts focused on the regions of Kazembe and Katanga in the south and south-east, respectively. Once the ivory in those regions dwindled, Arab traders moved north, into Manyema where Livingstone composed both the 1870 and 1871 Field Diaries (Sheriff 1987:187-90). Arab settlement in Manyema focused on a few locations, among them Nyangwe, Kasongo, and to a lesser degree Bambarre (Wisnicki 2013:211, Sheriff 1987:190), hence the reason Livingstone found himself in the latter village in the first place.

In this region, ivory abounded and so propelled Arab trader initiatives. Livingstone, for instance, complained of the “Californian gold fever at Ujiji” that prevented getting carriers and in one case described meeting “a band of Ujijian traders carrying 18000 lbs weight of ivory bought in this new field” (1870i:L, XLII). Livingstone also detailed the ongoing expansion of the trade, with references to traders pushing towards new frontiers, both west of the Lualaba River in the direction of the Lomami River and further north along the Lualaba, towards the rainforests of Legaland (e.g., 1870h:XVII-XVIII).

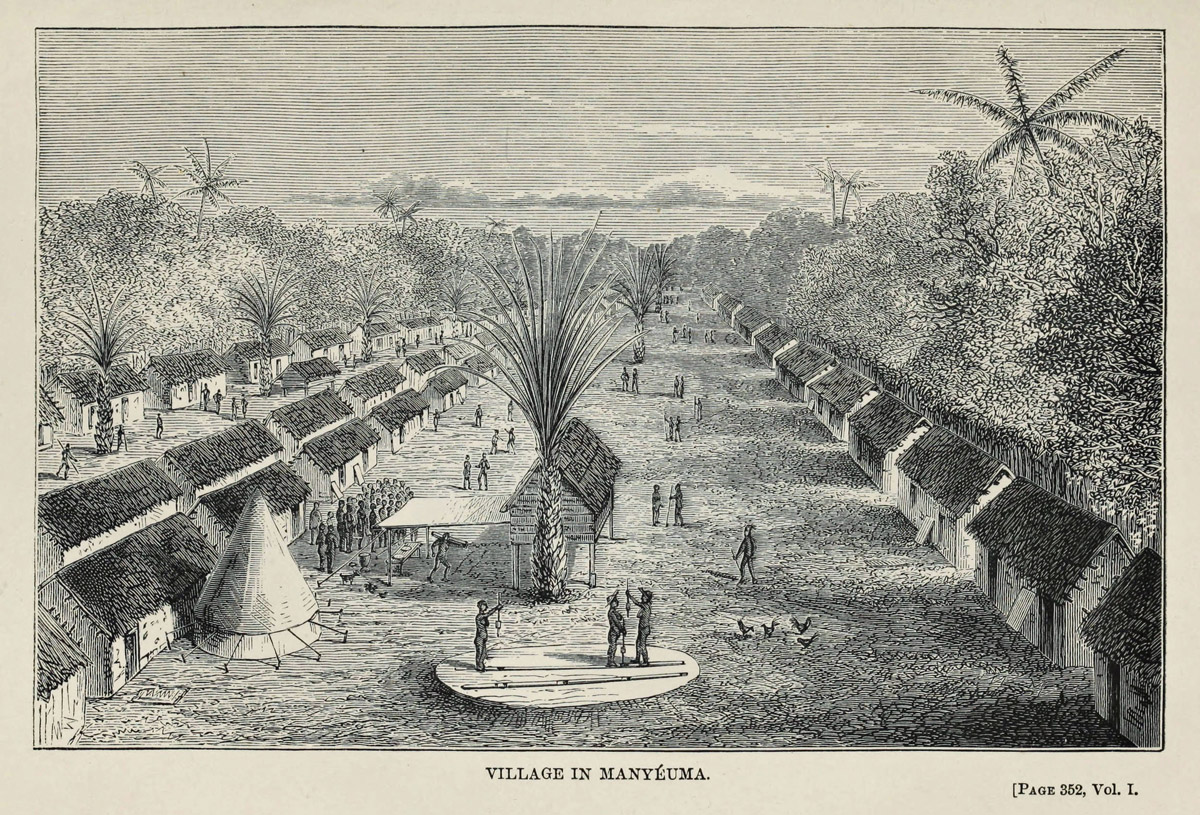

Village in Manyéuma. Illustration from Across Africa (Cameron 1877a,1:opposite 352). Courtesy of the Internet Archive. Idyllic illustrations such as this one and the next below contrast with the volatile circumstances occasioned by the arrival of Arab traders in the region, as documented in texts like the 1870 Field Diary.

The arrival of the traders in these regions, not unexpectedly, led to tensions with the local populations and created long-term hardships for those populations. Before the traders arrived, global trade had reached southern Manyema only indirectly. Rather, local economic influences predominated: “In the three decades between 1865 and 1895, the peoples of eastern [Congo] lost their autonomy, first to Afro-Arab traders in the service of the Sultan of Zanzibar and then to the Congo Free State in the service of King Leopold II of Belgium” (Northrup 1988:13). The populations of the region evolved complex relationships with the local geography, including the development of mixed agriculture and cattle-keeping, and built vibrant trade with the hunter-gatherer populations to the north (Northrop 1988:13-18, Wisnicki 2013:218ff.).

Livingstone characterized the diversity of these local populations, which did not correlate with Victorian expectations of African social organization or reigning European ideas of the nation, in different terms. He grouped the many regional populations under the single term “Manyema,” yet simultaneously faulted their lack of cohesion, especially at the political level: “The great want of the Manyema is national life. Of this they have none. Each headman is independent of every other” (1870g:{29}, cf. 1870i:XXIII).

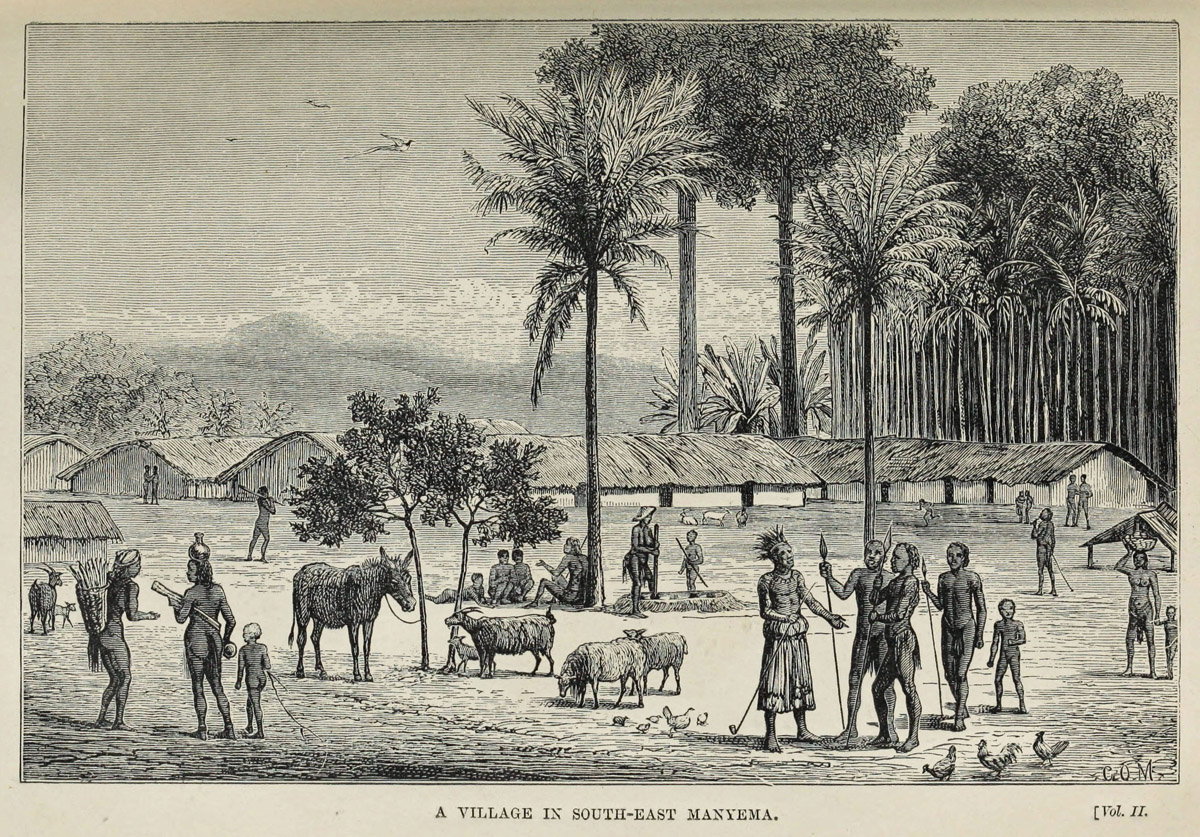

A Village in South-East Manyema. Illustration from Through the Dark Continent (Stanley 1878,2:opposite 82). Courtesy of the Internet Archive.

Although a rich and evolving cultural and economic fabric bound together the many communities in this part of central Africa (Vansina 1990), the Manyema region didn’t have a unifying military presence or a single, prominent leader like the Sultan of Zanzibar or the Kabaka of Buganda. As a result, Livingstone faulted the region for the lack of a visible centralized state and strong principal ruler.

Livingstone also argued that this political and social configuration brought technological development in the region to a “permanent halt,” led to war serving as the only solution for regional conflicts, and made relations among local populations particularly susceptible to interference by the Arab traders (1870h:XVII, XIX; 1870i:XXIII).

Bambarre People and Ujijians Top ⤴

The 1870 Field Diary characterizes the conflict between Arab traders and African populations in Manyema by progressively zeroing in on two specific groups: traders from Ujiji and residents of the village of Bambarre, today known primarily as the Bangubangu ethnic group (Maes and Boone 1935, Raucq 1952:35-36, Boone 1961, Maho 2009:34; cf. Vansina 1968:Map D and Butcher 2008:143-49).

Authorities suggest that the collective name of Bangubangu originated as an Arab or European appellation (Boone 1961:5; cf. Biebuyck 1973:19n.) and trace the genealogy of the group in two ways. Some foreground links to the Lega to the north (Biebuyck 1973:xix, 10, 18), while others count the Bangubangu among the people of Congo’s Kasai-Katanga region to the south, noting that ties between the Bangubangu and the neighboring Luba originated in the early nineteenth century (Raucq 1952: 42, 44; Vansina 1966:161-73, especially 162; cf. Wisnicki 2013:218-19).

| This map shows the present-day locations of (left to right) Nyangwe, Bambarre, Ujiji, and Zanzibar as well as the relative proximity of these locations to one another and to prominent geographical features such as Lake Tanganyika and the Indian Ocean. The correspondence of the historical locations to the present-day places is not necessarily exact, so the map serves only as a rough guide. Livingstone wrote most of the 1871 Field Diary in Nynagwe and most of the 1870 Field Diary in Bambarre. He kept the Unyanyembe Journal in Ujiji during the same period. |

These complex origins reflect a long-term reality. In the 1870 Field Diary, Livingstone makes a point to distinguish the inhabitants of Bambarre – the “Bambarre people” (1870i:XXXVI, XXXVII, 1870k:LXXIII) – from the Lega (1870i:XXXVII) and to trace the origin of the former to the Luba on the south and southwest. Yet Livingstone also indicates that Bambarre's residents do have some links with the Lega (Livingstone 1870h:XVII; cf. Cameron 1877a,2:66-69, who places more emphasis on the links between the Luba and the inhabitants of Bambarre).

Livingstone’s act of naming the local population and fixing it in Bambarre or more regionally in Manyema has an important discursive implication. The act enables Livingstone to introduce a key set of protagonists into his narrative, to characterize them, and to point to “the isolation in which they live” (1870b:[1], cf. Northrup 1988:19-20). Against these protagonists, Livingstone’s diary then pits the Arab traders and their followers or, to use Livingstone’s terms, the “Ujijians” or “Ujijian traders” (1870b:[69]; 1870e:XIII; 1870i:XXXV, XLII; 1871e:CI).

Ujiji, Looking North from the Market-Place, Viewed from the Roof of Our Tembé at Ujiji. Illustration from Through the Dark Continent (Stanley 1878,2:opposite 1). Courtesy of the Internet Archive.

Livingstone’s 1870 Field Diary embodies a first-hand chronicle of the arrival of these traders in Manyema and their forays into new regions to the west and north. The chronicle includes Livingstone’s eye-witness testimony of damage done by the traders, as when he reports having “passed through nine villages destroyed by the worthies who did not wish me to see more of their work” (1870b:[26]). The diary also records narratives of violence collected from the traders themselves (1870i:XXIX-XXXI, 1870k:LXXIV, 1870d:{23}-{24}).

In some cases, the violence bears an eerie ring of familiarity, particularly in the context of the marketplace massacre Livingstone himself would witness in July 1871 in Nyangwe. Passages from the 1870 Field Diary, such as the following, read almost as if they came from the later 1871 narrative of the events at Nyangwe: “these three then fired into a mass of men who collected one killed two another three & so on” (1870k:LXXIV; cf. 1871f:CXLVI ff.).

Given Livingstone’s close relations with some Arabs, their tendency towards violence proves difficult to reconcile. At times, Livingstone attempts to separate the main Arab traders from their followers and blames conflicts on the latter: “The nine villages and a [sic] 100 men killed by Katomba’s slaves at Nasangwa were all about a string of beads fastened to a powder horn which a [M]anyema man tried in vain to steal” (1870e:X).

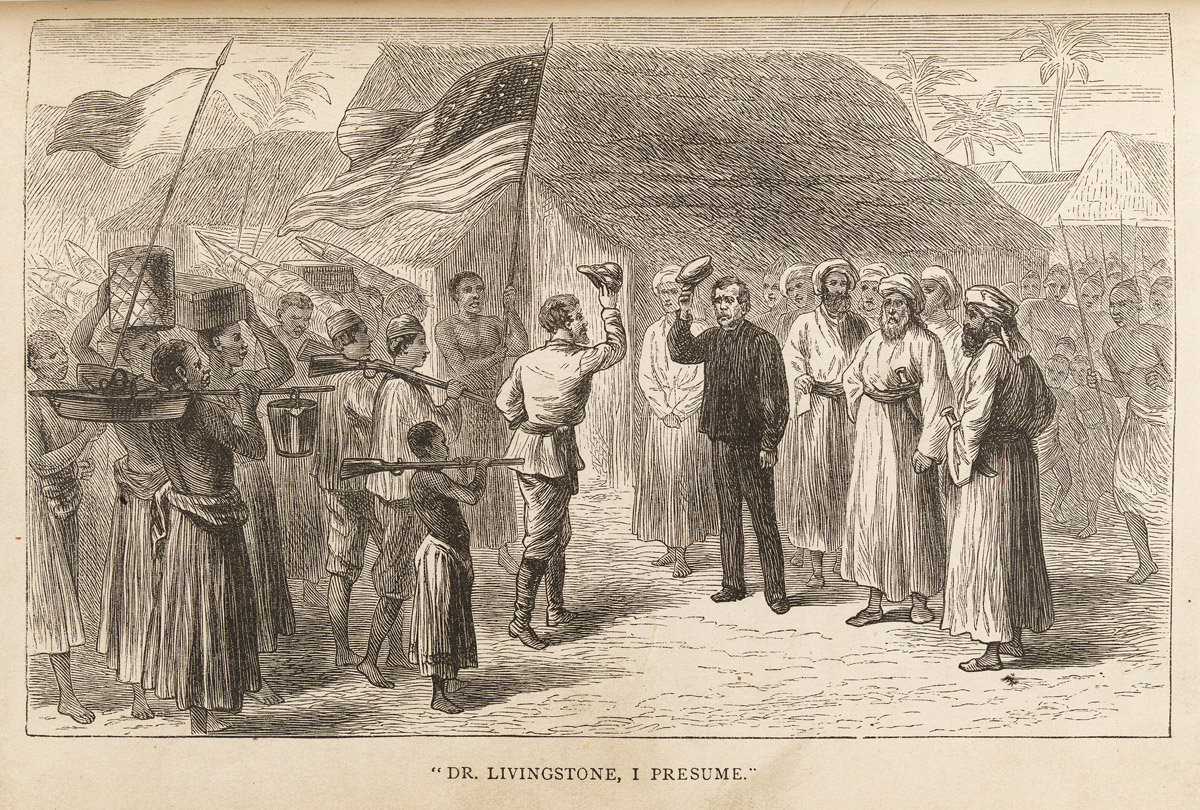

Dr. Livingstone, I Presume? Illustration from Stanley's How I Found Livingstone (1872,2:opposite 412). Courtesy of Edinburgh University Library. The focus on Livingstone and Stanley draws attention away from the fact that their meeting in Ujiji with a diverse array of individuals in attendance was driven less by individual preference or initiative and much more by broader economic forces and pressures due to the expansion of Zanzibar's trading empire into central Africa via Ujiji.

Elsewhere, he lumps the different groups together, differentiating only by degree: “The traders from Ujiji are simply marauders, and their people worse than themselves thirst for blood more than for ivory – Each longs to be able to tell a tale of blood, and Manyema are an easy prey” (1871e:XCVII).

While reflecting on the regional situation, Livingstone introduces an additional conflict, now at the ideological level, between Christianity and Islam. He finds that he simply cannot make sense of the contrast between his own commitment as a missionary – however nominal at this stage in his career – and the failure of the Arabs and their followers to pursue similar ambitions for spreading Islam (1870k:LXXIV, 1871e:C-CI).

-detail-article.jpg)

A processed spectral image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870k:LXXIV PCA_pseudo_32), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. In a passage that implicitly contrasts his conduct as missionary with that of Swahili traders (whom he conflates with Arab traders), Livingstone writes: "These Suaheli are the most cruel and bloodthirsty missionaries in existence and withal so impure in talk & acts - spreading syphilis Buboes & chancres - The Lord sees it."

These circumstances inspire some of the most vituperative language in the 1870 Field Diary. In reviewing the conduct of the Arab traders, Livingstone in turn assails the falsehood of those with whom he is personally acquainted, some of the foundational ideas of Islam and its holiest city, and, finally, the founder of the religion himself (1871e:LXXIX, LXXXI-LXXXIII, XCVIII).

One example of Livingstone’s language suffices to convey the whole: “[The cholera at Zanzibar] we get from Mecca filth – nothing was done to prevent the place being made a perfect cesspool of animals guts & ordure of men” (1871e:LXXIX; cf. 1874,2:96-98, where Waller has preserved only some of the relevant passages). Such passages – however they might read today – were not unusual in the Victorian era and reflected rising, late nineteenth-century concerns about the spread of Islam and an inevitable struggle between Christians and Muslims (Livingstone 2014:131-32; cf. Kennedy 2013:202).

Process, Narrative, Knowledge Top ⤴

The presence of such passages alongside others where Livingstone praises his Arab friends (e.g., 1870i:XLII, 1871e:LXXXIX-XCIV) also highlights the 1870 Field Diary’s role in capturing the experience of the field in nineteenth-century central Africa. The diary – effectively an unrevised process narrative – details Livingstone’s often unsuccessful attempts to resolve the incongruities between his personal experiences and guiding cultural and religious beliefs.

Such complexities lead Livingstone to develop a kind of narrative style new to the diaries from his last expedition to Africa. The style, particularly its rapid transitions between themes and events, enables Livingstone to alternate theories of the Nile River system, with:

- first-hand observations on local African cultural practices and social dynamics,

- reflections on his own travels and delays,

- complaints about his attendants,

- narratives of local events gathered from his informants,

- notes on the evolving state of his own health,

- discussion of personal grudges against individuals back home and in east Africa,

- and much, much more.

Together the entries take on a stream-of-consciousness form where representation of local priorities and concerns become layered upon Livingstone’s own experiences and observations as well as reflections on historical events and actors.

![A segment of Livingstone's Map of Central African Lakes [1869], [1]. Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/). A segment of Livingstone's Map of Central African Lakes [1869], [1]. Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/livingstone-central-africa-1870/liv_003006_0001-detail2-article.jpg)

A segment of Livingstone's Map of Central African Lakes [1869], [1]. Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. This undated map shows, in its lower half, Manyema and, in its upper half, Legaland. The village of Bambarre in the lower center of the map appears under the name of its chief Moenekuss. More importantly, the map demonstrates the scale of information that Livingstone managed to collect about the waterways of Legaland (which he never visited) and how this information could take the form of both cartographical detail (what Livingstone has mapped) and oral narrative (what Livingstone has captured in prose).

The overall narrative of the diary, including the scale of the information that Livingstone records, grows out of his unique situation and circumstances in 1870. Livingstone bashes contemporary “theoretical discoverers,” who pursued geographical research by integrating the observations of others rather than engaging in first-hand exploration (1870c:II). Yet Livingstone fails to acknowledge that he himself operates like a “theoretical” explorer, albeit one based in central Africa. He dreams of traveling like the Arab traders, but complex factors have halted his progress (e.g., 1870i:LIV-LV). To compensate, he gathers knowledge through interviews of the individuals that surround him.

The 1870 Field Diary shows Livingstone to be very well informed about local and regional events despite his immobility. Each group of traders that arrives in Bambarre, from whatever direction, further enlarges Livingstone’s store of knowledge. The scale of this knowledge best emerges through an enumeration of the locations from which Livingstone shares news in the 1870 Field Diary. These locations include:

1) Nearby villages such as Mamohela and Kasongo (1870b:[24]-[33], 1870i:XXIX);

2) Areas north, both along the Lualaba River to Nyangwe and further afield (1870b:[24]-[33], [41]-[45]; 1870e:X; 1870h:XIX; 1870i:XXI, LIV-LV; also see the map on 1871a: [LXXVI v.2]);

3) Legaland and the regions beyond as far as Lake Albert (1870b:[33]-[40]; 1870h:XVII; 1870i:XXIX-XXXI, LV [v.1]; also see the map on 1870f:[XIV v.2]);

4) Lubaland and Lunda to the south and, to the southwest, Katanga (1870c:[I], 1870f: XIV [v.1], 1870i:XXI);

5) Ujiji, the principal east African trading routes, the east coast of Africa, and Zanzibar (1870d:{21}-{22}; 1870e:XI; 1871b:LXXIX, LXXXI);

6) The areas north and northeast of Unyanyembe all the way to Buganda and Masaailand (1870f:[XIV v.2]; 1871b:LXXIX, LXXXI);

7) Mecca and the Arabian Peninsula (1870i:XL, 1871b:LXXXIII); and

8) Madagascar (1870i:XL).

Despite his apparent isolation, Livingstone collects information about vast swaths of central Africa, east Africa, and even more distant regions.

Slavers Revenging Their Losses. Illustration from the Last Journals (Livingstone 1874,1:opposite 56). Courtesy of the Internet Archive. Although such images appear to supplement Livingstone's written records of slave trading atrocities, the images also elide the fact that to gain this perspective Livingstone not only traveled with and relied on slave traders, but in many instances also befriended them.

Yet acquiring this knowledge – which derives from Arab and African informants – comes with a cost. To reach central Africa and to survive once there, Livingstone is compelled to form his close relationships with some Arab traders, as noted. This is not lost on the local African populations. In the eyes of these populations, Livingstone’s continuing associations with the Arab traders and his own followers undercut and even trump his activities on behalf of local Africans.

Sometimes the local populations respond favorably to Livingstone and recognize his intentions, but at other times they refuse to make distinctions and are “outspoken in asserting [the] identity [of Livingstone and his attendants] with the cruel strangers” (Livingstone 1870e:XIII, 1870i:XLIII, cf. 1866-72:[652], Stanley 1878,2:79-80).

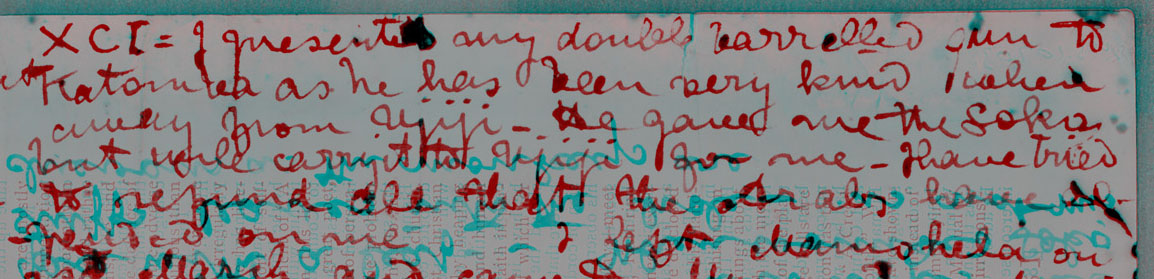

A processed spectral image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871e:XCI pseudo_v4), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. In this passage, Livingstone discusses the kindness of some Arab traders and notes his attempts to reciprocate that kindness, including presenting one such trader (Katomba) with a "double barrelled gun."

Such moments reflect deeper affinities. Early on, Livingstone cites the role of his Nassicker attendants in taking slaves and in killing local inhabitants in imitation of the Arab traders (1870b:[55]-[62], 1870i:LIII). Later he documents how the freed Banian slaves sent to Livingstone by John Kirk, the British political agent at Zanzibar, extend the Nassicker model of violence against locals (1871b:LXXXIV, 1871e:XCI-XCIV, CI). In each case, Livingstone admits his complicity in bringing such violence to central Africa, but either justifies the decision (1870i:LII-LIV) or attempts to assert his personal innocence: “I am clear of blood guiltiness” (1871e:CI).

Livingstone’s diary thus offers a compelling record of the experience in the central African field. The narrative’s oscillating, heterogenous style captures the conflicting pressures Livingstone faces as a Christian explorer and geographer committed to preventing violence against local populations in Manyema but simultaneously compelled to operate within the confines of Zanzibar’s trading empire, relying on a variety of individuals with conflicting loyalties, including Arabs, freed Banian slaves, and Nassicker attendants.

Informed Observation Top ⤴

Livingstone’s decision to visit Maneyma – the first European to do so and among the first to visit this whole part of central Africa – and his extended sojourn in Bambarre also lead to a unique transformation in his composition practices as a diarist. He begins to capture his observations about the local cultures at a level of detail that distinguishes the 1870 Field Diary from the majority of the 20-odd other field diaries and notebooks that Livingstone kept on this final expedition to Africa.

The presence of such information would have had a complex resonance with Livingstone’s contemporaries and, in fact, may have reflected an opposition in professional standards. The content of the information would have satisfied professional expectations for ethnographic information gathered in the field, but Livingstone’s methods, particularly his heavy reliance on informants, would have undermined the credibility of his geographical pronouncements (Kennedy 2013:132, 199, cf. 158). Victorian geographers considerd any data not collected through first-hand observation as inferior and even dubious, as most famously in the case of John H. Speke, who twice (1858, 1862) visited Lake Victoria – the lake now accepted as the real source of the Nile – but failed to convince contemporaries of his claims because of recourse to second-hand information (Wisnicki 2008).

![David Livingstone, Annotations on Map from John H. Speke, Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile (1863), [1869-73]:[1], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/). As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). David Livingstone, Annotations on Map from John H. Speke, Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile (1863), [1869-73]:[1], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/). As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/livingstone-central-africa-1870/liv_003181_0001-detail2-article.jpg)

David Livingstone, Annotations on Map from John H. Speke, Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile (Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons, 1863), [1869-73]:[1], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. Speke's dubious geographical practices (by Victorian standards) raised serious questions about his results among contemporaries such as Livingstone, who has here altered Speke's cartographical pronouncements by breaking up Lake Victoria into a series of lakes, while adding a dotted red line that could ultimately allow him, Livingstone, to claim a more southerly source for the Nile.

In collecting his information, Livingstone usually follows one of two trajectories. Most predictably, the diary includes a variety of ad hoc observations as when Livingstone describes funeral rites, generalizes about the appearance of the populations, outlines agricultural practices, and discusses religious beliefs in Manyema (1870b:[1]-[6], [44]-[45]; 1870e:XII; 1870i:XXVI). Thanks to his medical background, he also includes notes on the presence of ailments, the use of local medicines, and the role of the traders in spreading STIs (e.g., 1870d:{19}-{21}, 1870e:X, 1870i:LXIII-LV).

At the same time, Livingstone makes a sustained effort to explore and document social conduct in Bambarre and Manyema. The diary opens with a series of anecdotes about the behavior of regional chiefs, includes a story about the death of the oldest son of Moenekuss (the headman of Bambarre), and describes the habits of another regional headman, Merere, and his father (1870b:[7]-[12], 1870g:{29}-{30}, 1870i:XXVIII-XXIX).

Livingstone also devotes a fair amount of attention to the details of Manyema villages, explores regional trading dynamics (a topic to which he will return at length in the 1871 Field Diary), and touches on local systems of justice (1870b:[43]-[45], [63]-[70]; 1870j:LXVII-LXVIII). At one point Livingstone even develops an annotated genealogy of the house of Charura, a deceased African headman, to which genealogy he, Livingstone, later returns to provide additional detail (1870k:LXXII, 1871b:LXXXII).

![An image of a page from Livingstone's Notebook III (22 July-7 Oct. 1871:[75]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Images of the Livingstone manuscripts from the David Livingstone Centre are copyright University of Glasgow Photographic Unit. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page from Livingstone's Notebook III (22 July-7 Oct. 1871:[75]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Images of the Livingstone manuscripts from the David Livingstone Centre are copyright University of Glasgow Photographic Unit. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/livingstone-central-africa-1870/liv_000022_0075-article.jpg)

An image of a page from Livingstone's Notebook III (22 July-7 Oct. 1871:[75]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Images of the Livingstone manuscripts from the David Livingstone Centre are copyright University of Glasgow Photographic Unit. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. A notebook page onto which Livingstone has copied both vocabulary and cultural observations first recorded in the 1870 Field Diary. Because Livingstone died prematurely on his final journey, his ultimate intentions for such material remain unknown.

Such information, even if it only appears in flashes, recenters the 1870 Field Diary on local African populations and acknowledges their independent motivations, while pushing the story of Livingstone’s own efforts as an explorer, abolitionist, and missionary to the narrative margins. The 1870 Field Diary thus begins to portray Bambarre and the surrounding area as a vibrant regional location, one filled with diverse and clearly differentiated individuals that are linked by complex social dynamics and driven by complex, self-generated objectives that Livingstone may not fully understand but that he gradually begins to recognize and acknowledge.

Close critical attention to this local central African universe also shows similar, independent forces that undermine any narrative of victimization that Livingstone might try to impose on the local African populations. The forces take the form of active, inventive, and sustained resistance by the local populations to the Arab traders, their followers, and Livingstone himself.

A processed spectral image of a page of the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870h:XVII pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. This passage, which includes a map of rivers linked to Lake Tanganyika and documents a reported conversation between Arab traders and representatives of the Lega ethnic group, succinctly encapsulates the extreme hostility of central African populations to the traders: "[...] Balegga very unfriendly – collected in thousands – we came to buy ivory - said Hassani & if there is none we go away | 'Nay' shouted they, 'you came to die here' then shot with arrows - when shot was returned they fled & would not come to receive the captives."

It is no secret that the local populations in Manyema resent the arrival of the Arabs, as in the case of the Bira ethnic group who, notes Livingstone, “are now enraged at seeing Ujijians pass into their ivory field” (1870b:[69]). This anger translates into multiple skirmishes with the Arab traders.

One example gives a sense of the whole: “Moenemokia killed 2 Arab agents & took their guns […] Elsewhere they made regular preparation to have a fight with Dugumbe's people just to see who was strongest. They with their spears & wooden shields or the Arabs with what in derision they called tobacco pipes (guns)[.] They killed eight or nine Arabs” (1870b:[59], [61]-[62]; cf. 1870i:XXXVIII). The local populations not only resist the Arab traders, but kill them and their followers, and, notably, capture their firearms. In other words, the populations act independently of the traders – i.e., don’t just get caught up in the expansionist agenda that the traders seek to impose upon them – and, at least occasionally, succeed in turning the tables on the traders.

Cannibalism in 1870 Top ⤴

Later history would show such overt tactics to be ineffective in the face of a growing and ever more aggressive and organized Arab slave trade. But Livingstone’s diary captures the emergence and effects of the resistance strategies at a moment, in 1870, when the future remains undecided. On one hand, the courage of the local populations draws respect from the traders: “The Mamohela horde is becoming terrified [–] Every party going to trade has lost three or four men and the last foray lost ten and saw that the Manyema can fight” (1870i:XXXIV, cf. XXXI). On the other, Livingstone’s diary also tracks the increasing skill of the local populations in engaging in more subtle forms of warfare, as in the case of the Merere, a local headman and descendant of Charura.

In a brief narrative included near the end of the 1870 Field Diary, Merere first turns against the Arabs, killing one and robbing others “of all they had,” then repents of his behavior and indicates that he will “repay all loses” (1871b:LXXX). Livingstone seems unsure of how to characterize this behavior: “He looks as if insane & probably is so” (1871b:LXXX). Merere emerges as a cipher, an individual whose motivations and conduct exceed Livingstone’s abilities to assess them definitively.

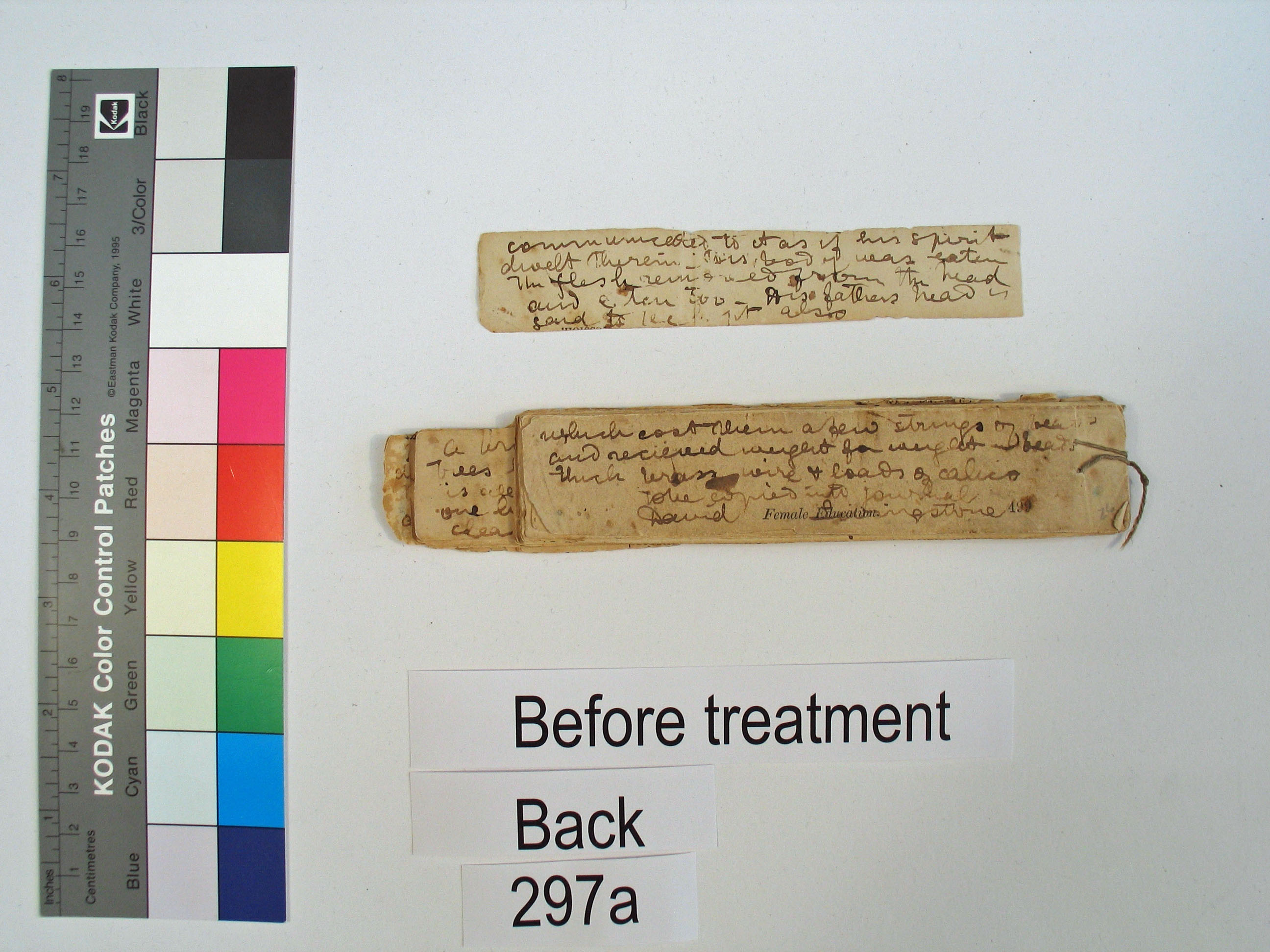

The first gathering of the 1870 Field Diary before conservation by Helen Creasy of the Scottish Conservation Studio. Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The detached page, the earliest surviving page of the gathering, refers to the apparent practice of cannibalism in Bambarre.

In such ways, the African populations residing in or near Bambarre begin to cultivate indeterminate, unpredictable behavior as a method of resistance alongside more open physical violence. The 1870 Field Diary oscillates between offering Livingstone’s rationalizations for these actions and representing these populations (and their tactics) on their own terms, even if that forecloses Livingstone’s attempts to rationalize events.

The 1870 Field Diary’s running commentary on the practice of cannibalism exemplifies this devleopment. Other explorers, such as Henry M. Stanley, document instances of local African populations pretending to be cannibals in other to resist Arab traders (1876–1877, entries after 25 October 1876; also see Wisnicki 2013:226) and that seems to be the case in the 1870 Field Diary as well.

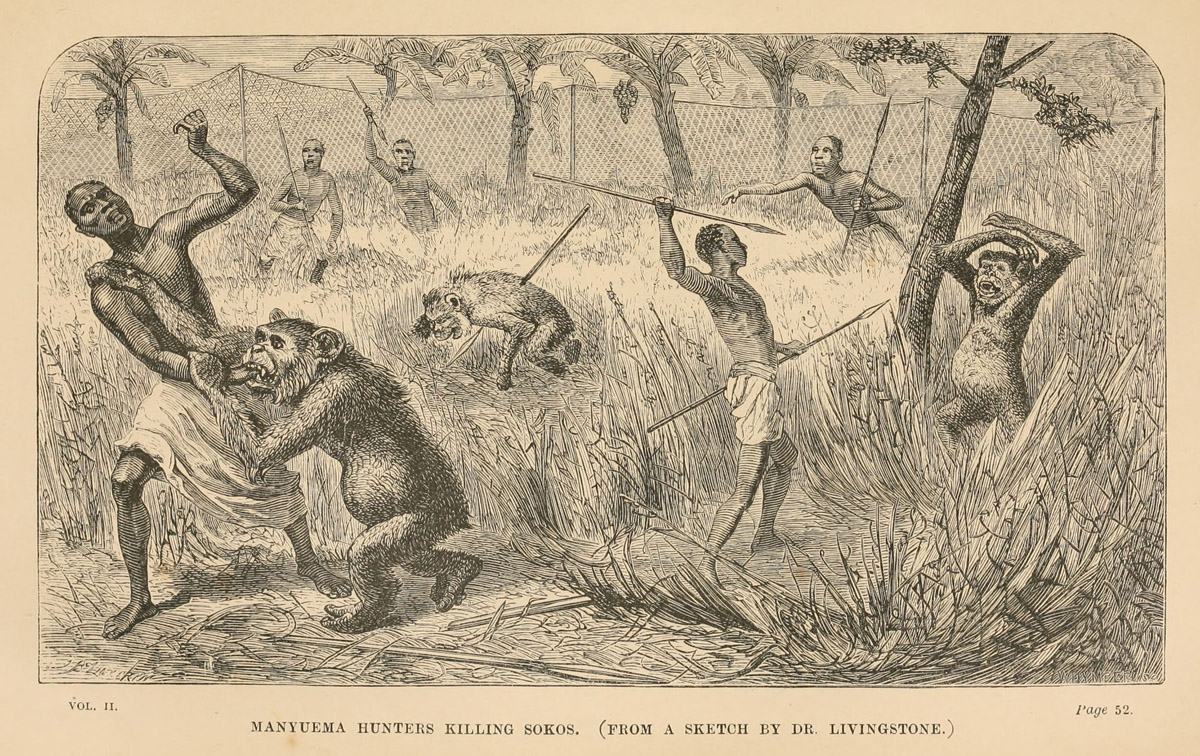

The diary begins with a discussion of cannibalism in relation to funeral practices (1870b:[1]-[6]), and, later, Livingstone offers a genealogy of the practice by linking it to the practice of eating sokos (i.e., gorillas) (1870c:IV).

Manyuema Hunters Killing Sokos. (From a Sketch by Dr. Livingstone.) Illustration from the Last Journals (Livingstone 1874,2:opposite 52). Courtesy of the Internet Archive. Although Livingstone's original sketch has not been located, the general characteristics of his drawing style (as seen in his other writings) suggest that the illustrator has here distorted the features of the Africans to reflect Victorian stereotypes of African savagery and, possibly, to accentuate Livingstone's hypothesis "that eating sokos was the first stage by which [the inhabitants of Manyema] arrived at being cannibals," which appears on the page directly following this illustration (Livingstone 1874,2:53; cf. 1870b:IV).

Yet such assertions stand alongside more tentative statements. Livingstone opens his draft letter to Lord Stanley by describing Manyema as the country of “the reputed cannibals” and elsewhere notes that the population now engages in the practice in secret because of the manifest disgust of the traders (1870i:XLI, emphasis added; 1870k:LXXV).

Livingstone thus indicates that his characterizations may be based more on hearsay than the direct observation requisite for the professional practice of Victorian-era exploration. This move introduces an irreducible strand of ambiguity into the narrative of the 1870 Field Diary that Livingstone himself later foregrounds.

An image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871i:XLI). Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The opening of a copy of the letter to Lord Stanley (15 Nov. 1870) that Livingstone embedded in the 1870 Field Diary. In this opening, Livingstone states the he writes from Manyema, the country of "the reputed cannibals." (emphasis added).

When discussing the population of Bambarre just prior to leaving – i.e., when his information should be most accurate due to his long sojourn in the village – he first states that “their cannibalism is doubtful” only to reverse himself a few pages later by indicating that the locals are “undoubtedly cannibals” (1871b:LXXXIII, LXXXVII).

In the 1870 Field Diary, Livingstone never resolves this contradiction or, alternatively, never manages to circumscribe it in terms that are comprehensible to him. Rather, the diary’s narrative framework summons up an alternative African epistemological system – even if only tacitly – that stands alongside of the British one in which Livingstone operates. Livingstone, in turn, leaves the people of Bambarre on this note and heads for Nyangwe, where he will turn to his remaining iron gall ink and a torn-up copy of The Standard to compose the 1871 Field Diary.

Silences in the Published Record Top ⤴

The fate of these passages on cannibalism underscores the challenges posed overall in interpreting the narrative materials produced by Livingstone during this period. As Livingstone first and then, posthumously, his friend Horace Waller edited these materials, the former’s cultural observations took on a more abridged form, then became subsumed within biographical details, thereby setting up a long-standing history of critical response.

For instance, when Livingstone later revised the 1870 Field Diary into the more polished Unyanyembe Journal form, he collected the many references to cannibalism into a single longer passage and conflated them with general observations about violence in Manyema (1866-72:[646]-[648]). Horace Waller, conversely, in producing the text of the Last Journals (Livingstone 1874), kept most of the 1870 Field Diary’s random references to cannibalism intact. Yet Waller considerably dampened the immediate, fragmentary nature of the diary and its unresolved tensions by tampering with the text, combining the diary’s text with that of the journal, and introducing a series of extra-textual digressions (see Livingstone 1874,2:52, 55, 61, 62, 63-64, 65, 86-87, 88, 89-92, 94-95, 108).

![A raw spectral image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871b:LXXXIII pack16 [RABL] with brightness increased to 121 in Photoshop Elements 12.0). Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). A raw spectral image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871b:LXXXIII pack16 [RABL] with brightness increased to 121 in Photoshop Elements 12.0). Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/livingstone-central-africa-1870/liv_000209_0006_pack16_RABL+121-article.jpg)

A raw spectral image of a page from the 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871b:LXXXIII pack16 [RABL] with brightness increased to 121 in Photoshop Elements 12.0). Copyright National Library of Scotland and, as relevant, Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. Such monochromatic images form the basis of all the processed spectral images published in the present edition. The project team captured this image, which reveals elements of page topography invisible under natural light, using a blue light (465 nm) projected unto the page at an oblique or "raking" angle from the left side. The opening of this page is cited below.

In so doing, Waller chose to prioritize a narrative in which Africans are cast as reactive victims, as Livingstone before him. This editorial move cut against the representation of an intricate central African universe and discursive framework whose differentiated actors could not only evolve as self-driven individuals, but also, as part of that evolution, develop nuanced and creative methods of resistance:

[M]y long detention in Manyema leads me to believe that they are truly a bloody people – cold blooded murders are frightfully common and they say that but for our presence they would ^ be still more frequent – They have no fear of spears and shields – guns alone frighten them – they tell us frankly and quite truly that but for our firearms not one of us should ever return to his country. (1871b:LXXXIII)

Such passages, omitted from both the Unyanyembe Journal and Last Journals and silenced till now, show a rebellious local population, innovative in their tactics of instilling fear in their adversaries, skilled in combining brute force with sophisticated psychological strategies. These passages, which foreground the independence of mind of these populations, stand in stark contrast to more common, stereotypical Victorian representations of African helplessness. The passages also underscore that editions such as this one embody only an initial step in a full-scale, ever-more-necessary, historical reassessment of the manuscript record of exploration.

Works Cited: Primary Sources Top ⤴

[View the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project's full bibliography.]

Cameron, Verney Lovett. 1877a. Across Africa. 2 vols. London: Dalby, Isbister & Co.

Livingstone, David. 1866-72. Unyanyembe Journal. 28 Jan. 1866-5 Mar. 1872. 1115. David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1870b. Fragment of 1870 Field Diary. 17, 24 Aug. 1870. 297a. David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1870c. Fragment of 1870 Field Diary (I-IV). 18, 24 Aug. 1870. Add. MS. 50184, f. 169. British Library, London, England.

Livingstone, David. 1870d. Fragment of 1870 Field Diary. 25 Aug.-8 Oct. 1870. Transcribed by Agnes Livingstone. Waller MSS. Afr. s. 16.6. Bodleian Library. Weston Library, Oxford, England.

Livingstone, David. 1870e. Fragment of 1870 Field Diary (X-XIII). 10 Oct. 1870. MS. 10703, ff. 1-2. National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1870f. Fragment of 1870 Field Diary (XIV). 13 Oct. 1870. 297b. David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1870g. Fragment of 1870 Field Diary. 16 Oct. 1870. Transcribed by Agnes Livingstone. Waller MSS. Afr. s. 16.6. Bodleian Library. Weston Library, Oxford, England.

Livingstone, David. 1870h. Fragment of 1870 Field Diary (XVII-XX). 19-31 Oct. 1870. 297d. David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1870i. Fragment of 1870 Field Diary (XXI-LXI). 3-15 Nov. 1870. MS. 10703, ff. 3-23. National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1870j. Fragment of 1870 Field Diary (LXII-LXIX). 22 Nov.-10 Dec. 1870. 297e. David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1870k. Fragment of 1870 Field Diary (LXX-LXXV). 12-23 Dec. 1870. MS. 10703, ff. 24-26. National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1871a. Fragment of 1870 Field Diary (LXXVI). 16 Jan. 1871. 297b. David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1871b. Fragment of 1870 Field Diary (LXXVIII-LXXXVII). 24 Jan.-19 Feb. 1871. MS. 10703, ff. 27-31. National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1871e. Fragment of 1870 Field Diary (LXXXVIII-CI). 21 Feb.-22 Mar. 1871. MS. 10703, ff. 32-35. National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1871f. Fragment of 1871 Field Diary (CII-CLXIII). 23 Mar. 1871-11 Aug. 1871. 297b, 297c. David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1874. The Last Journals of David Livingstone in Central Africa, from 1865 to His Death, edited by Horace Waller. 2 vols. London: John Murray.

Stanley, Henry Morton. 1872. How I Found Livingstone: Travels, Adventures, and Discoveries in Central Africa; Including Four Months’ Residence with Dr. Livingstone. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington.

Stanley, Henry Morton. 1876-77. Field Notebook, labeled "Aug 21d 1876" (21 Aug. 1876 - 3 Mar. 1877). Musée Royal de l'Afrique Centrale, Tervuren.

Stanley, Henry Morton. 1878. Through the Dark Continent, or The Sources of the Nile around the Great Lakes of Equatorial Africa and down the Livingstone River to the Atlantic Ocean. 2 vols. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington.

Works Cited: Secondary Sources Top ⤴

Bayly, Paul. 2014. David Livingstone: Africa’s Greatest Explorer: The Man, the Missionary and the Myth 1813–1873. Stroud: Foothill Media.

Bennet, Norman Robert. 1974. “The Arab Impact.” In Zamani: A Survey of East African History, edited by B.A. Ogot, 210–28. Nairobi: East African Publishing House and Longmans of Kenya.

Bennett, Norman Robert. 1986. Arab versus European: Diplomacy and War in Nineteenth-Century East Central Africa. New York: Africana Publishing Company.

Biebuyck, Daniel. 1973. Lega Culture: Art, Initiation, and Moral Philosophy among a Central African People. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Boone, Olga. 1961. Carte Ethnique Du Congo: Quart Sud-Est. Tervuren: Musee Royal de l’Afrique Centrale.

Bridges, Roy C. 1973. “The Problem of Livingstone’s Last Journey.” In Proceedings of a Seminar Held on the Occasion of the Centenary of the Death of David Livingstone at the Centre of Africa Studies, University of Edinburgh, 4th and 5th May 1873, 163–85. Edinburgh: Centre of African Studies, University of Edinburgh.

Bridges, Roy C. 1977. “The Documentation of David Livingstone: Some New Materials.” In Hakluyt Society Annual Report and Statement of Accounts 1977-1978, 1–8.

Bridges, Roy C. 1987. “Nineteenth-Century East African Travel Records with an Appendix on 'Armchair Geographers' and Cartography.” Paideuma 33: 179–96.

Bridges, Roy C. 1988. “Elephants, Ivory and the History of the Ivory Trade in East Africa.” In The Exploitation of Animals in Africa: Proceedings of a Colloquium at the University of Aberdeen, March 1987, 193–220. Aberdeen: Aberdeen University African Studies Group.

Butcher, Tim. 2008. Blood River: The Terrifying Journey Through The World’s Most Dangerous Country. New York, New York: Grove Press.

Buxton, Meriel. 2001. David Livingstone. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Campbell, R.J. 1929. Livingstone. London: Ernest Benn Ltd.

Coupland, Reginald. 1945. Livingstone’s Last Journey. London: Collins.

Helly, Dorothy O. 1987. Livingstone’s Legacy: Horace Waller and Victorian Mythmaking. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press.

Hyam, Ronald. 2002. Britain’s Imperial Century, 1815-1914: A Study of Empire and Expansion. Third Edition. Houndsmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England: Palgrave Macmillan.

Jeal, Tim. 1973. Livingstone. London: Heinemann.

Jeal, Tim. 2011. Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure. New Haven, CT; London: Yale University Press.

Kennedy, Dane. 2013. The Last Blank Spaces: Exploring Africa and Australia. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Lewis-Jones, Huw, and Kari Herbert. 2016. Explorers’ Sketchbooks: The Art of Discovery & Adventure. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd.

Listowel, Judith. 1974. The Other Livingstone. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Livingstone, Justin D. 2014. Livingstone’s Lives. A Metabiography of Victorian Icon. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Livingstone, Justin D. 2015. “Livingstone’s Posthumous Reputation.” First edition. Livingstone Online, directed by Adrian S. Wisnicki, Megan Ward, Anne Martin, and Christopher Lawrence. New version, second edition. College Park, MD: University of Maryland Libraries.

MacKenzie, John M. 1996. “David Livingstone and the Worldly After-Life: Imperialism and Nationalism in Africa.” In David Livingstone and the Victorian Encounter with Africa, edited by John M. MacKenzie, 201–16. London: National Portrait Gallery.

Macola, Giacomo. 2016. The Gun in Central Africa. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press.

Maes, J., and O. Boone. 1935. Les Peuplades Du Congo Belge: Nom et Situation Geographique. Bruxelles: Imprimerie Veuve Monnom.

Maho, Jouni Filip. 2009. "NUGL Online: The Online Version of the New Updated Guthrie List, a Referential Classification of the Bantu Languages." N.p.: n.p.

Northcott, Cecil. 1973. David Livingstone: His Triumph, Decline and Fall. Guildford: Lutterworth.

Northrup, David. 1988. Beyond the Bend in the River: African Labor in Eastern Zaire, 1865-1940. Athens, OH: University of Ohio Press.

Pettitt, Clare. 2007. Dr. Livingstone, I Presume?: Missionaries, Journalists, Explorers, and Empire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Ransford, Oliver. 1978. David Livingstone: The Dark Interior. London: John Murray.

Raucq, Paul. 1952. Notes de Geographie Sur Le Maniema. Bruxelles: Institut Royal Colonial Belge, Section des Sciences Naturelles et Medicales.

Reid, Richard J. 2012. Warfare in African History. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Renault, Francois. 1989. “The Structures of the Slave Trade in Central Africa in the 19th Century.” In The Economics of the Indian Ocean Slave Trade in the Nineteenth Century, edited by William Gervase Clarence-Smith, 146-65. London: Cass.

Rockel, Stephen J. 2006. Carriers of Culture: Labor on the Road in Nineteenth-Century East Africa. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Ross, Andrew C. 2002. David Livingstone: Mission and Empire. London: Hambledon & London.

Seaver, George. 1957. David Livingstone: His Life and Letters. New York: Harper & Brothers.

Sheriff, Abdul. 1987. Slaves, Spices and Ivory in Zanzibar: Integration of an East African Commercial Empire into the World Economy, 1770-1873. Oxford: James Currey.

Simpson, Donald. 1976. Dark Companions: The African Contribution to the European Exploration of East Africa. London: Paul Elek.

Tomkins, Stephen. 2013. David Livingstone: The Unexplored Story. Oxford: Lion Hudson.

Vansina, Jan. 1966. Introduction a l’Ethnographie Du Congo. Kinshasa: Universite Lovanium.

Vansina, Jan. 1968. Kingdoms of the Savanna. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Wilson, Anne. 1972. “Long Distance Trade and the Luba Lomami Empire.” Journal of African History, no. 13: 575–89.

Wisnicki, Adrian S. 2008. "Cartographical Quandaries: The Limits of Knowledge Production in Burton’s and Speke’s Search for the Source of the Nile." History in Africa 35 (2008): 455-79.

Wisnicki, Adrian S. 2010. "Rewriting Agency: Baker, Bunyoro-Kitara, and the Egyptian Slave Trade." Studies in Travel Writing 14 (1): 1-27.

Wisnicki, Adrian S. 2013. “Victorian Field Notes from the Lualaba River, Congo.” Scottish Geographical Journal 129 (3-4): 210–39.

Youngs, Tim. 1994. Travellers in Africa: British Travelogues, 1850-1900. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

![Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_013723_0001-new-carousel_0.jpg)

![Processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's "Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal" (Livingstone 1870a:[3] pseudo_v4_BY), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's "Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal" (Livingstone 1870a:[3] pseudo_v4_BY), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000211_0003_pseudoBY_940_by_592-carousel.jpg)

![David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, [1869], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland: CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, [1869], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland: CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_003006_0001-new-carousel_0.jpg)

![Sultan of Zanzibar [Barghash bin Said]. Illustration from James E. Ritchie, The Pictorial Edition of the Life and Discoveries of David Livingstone, 2 vols (London and Edinburgh: A. Fullarton & Co., 1876-1879), 2:np. Copyright Adrian S. Wisnicki. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). Sultan of Zanzibar [Barghash bin Said]. Illustration from James E. Ritchie, The Pictorial Edition of the Life and Discoveries of David Livingstone, 2 vols (London and Edinburgh: A. Fullarton & Co., 1876-1879), 2:np. Copyright Adrian S. Wisnicki. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/livingstone-central-africa-1870/Sultan-Pictorial-3-article.jpg)