The Unyanyembe Journal: An Overview

Cite page (MLA): Ward, Megan, and Adrian S. Wisnicki. "The Unyanyembe Journal: An Overview." In Livingstone's Final Manuscripts (1865-1873). Megan Ward and Adrian S. Wisnicki, dirs. Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. University of Maryland Libraries, 2018. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/b37eb894-0985-448c-a9b2-da5c4a5dcdb8.

This essay introduces Livingstone’s Unyanyembe Journal (1866-72), the almost 800-page bound volume that Livingstone used to make his most lasting record of his final journey to Africa. It covers the journal’s dates and places, Livingstone’s thematic concerns, and the conflicts he faced as he created this record. The essay closes by considering Livingstone’s rhetorical situation as he writes the Unyanyembe Journal in Africa, among African and Arab populations, but for a primarily British audience.

Introduction Top ⤴

[View the critical edition or download a basic reading copy of the Unyanyembe Journal.]

Livingstone’s Unyanyembe Journal (1866-72) gets its name from the town of Unyanyembe, in present-day Tanzania. In this journal (UJ for short), Livingstone records highlights of his final trip to Africa, from 1865 until 1872. Often he copies these highlights over, in revised and/or expanded form, from his field diaries. The Unyanyembe Journal is the record upon which Horace Waller based the posthumously-published Last Journals (Livingstone 1874; also see Helly 1987). In it, Livingstone records his journey from Bombay to Zanzibar, up the river Rovuma to Lake N’Yassa and then north to Lake Tanganyika. From there, he travels west to Lake Moero and, from there, south to Lake Bangweolo. At this point, he makes his way back to Lake Tanganyika, travelling up the eastern shore and making a detour to the Taboro region and leaving the journal in the town of Unyanyembe.

| Images of the cover and of a page of the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[1], [7]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. On one of the first pages of the journal (right; bottom in mobile), Livingstone writes a note dated 14 March 1872 where he records sending the journal with Henry M. Stanley from Unyanyembe back to Britain. |

From that point of Livingstone's departure from Unyanyembe, the entries in the journal are created after the fact, based on the field diaries that he keeps as he journeys west to Bambarre and Nyangwe. He retrieves the journal in 1871, creating these after-the-fact entries and copying letters into it while also adding new material until he sends the journal back to England with Henry M. Stanley in 1872.

As he rewrites his field diary entries into the journal, Livingstone documents his further travels from Unyanyembe to Ujiji, then across Lake Tanganyika and west to region of Manyema (which includes the villages of Bambarre and Nyangwe). From there, he retraces his steps back to Ujiji, where he first meets Henry Morton Stanley and eventually entrusts the UJ to him.

Visit of Arabs to Livingstone and Stanley at Unyanyembe. Illustration from Review of Stanley's How I Found Livingstone (Anon. 1872:485), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland

Throughout this journey, Livingstone relies on help from the porters he has brought with him, as well as additional guides and porters hired as he goes. The UJ records information about the Arab slave trade; religious observations and missionary work; ecological, geological, medical, and technological information; observations about eastern and central African cultures; exploration and geography; and British and local politics.

The UJ differs from Livingstone’s field diaries in that it primarily functions as a record of important information rather than on-the-fly notations. Livingstone copies key documents and data into it, as well as the day-to-day experiences he determines are worth preserving. Its final form is much more like a book than a journal, including the index he creates at the end. The last several hundred pages contain many copies of important letters. Throughout there are rainfall and altitude tables, drawings, vocabulary charts, supply requests, and lists (e.g., 1866-72:[287], “Fishes of Liemba”).

| Images of a page of the Unyanyembe Journal as well as of the spine and fore edge (Livingstone 1866-72:[296], [775], [776]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The page at left (top in mobile) represents a typical page of the journal. The main text runs continuously from the top to the bottom of the page, while Livingstone adds marginal dates at the points where, roughly, entries for new dates begin. Sometimes the placement of dates coincides with a paragraph break, sometimes not. |

In this, the UJ constitutes what Roy Bridges labels a “second stage” document, one that “omitted, amended or expanded the material in the notebooks” (1977:4). The UJ is clearly a work in progress, however, as Livingstone sometimes introduces notes to himself or future editors, as when he amends a note, “(2nd April left very ill with dysentery – This is private)” (1866-72:[272]). Moreover, evidence suggests that Livingstone adds at least some such notes long after the fact, reinforcing his focus on future publication.

Slavery and Christianity Top ⤴

Among the UJ’s most consistent concerns is slavery: its facts and effects as well as Livingstone’s philosophical and ethical objections. The journal starts with a description of the Zanzibar slave market, which drives the central and emerging west-central African slave trades. Livingstone’s objection to slavery is that he believes the condition of being enslaved corrupts one for life and makes people “slaves in heart,” even if they are freed (1866-72:[314]).

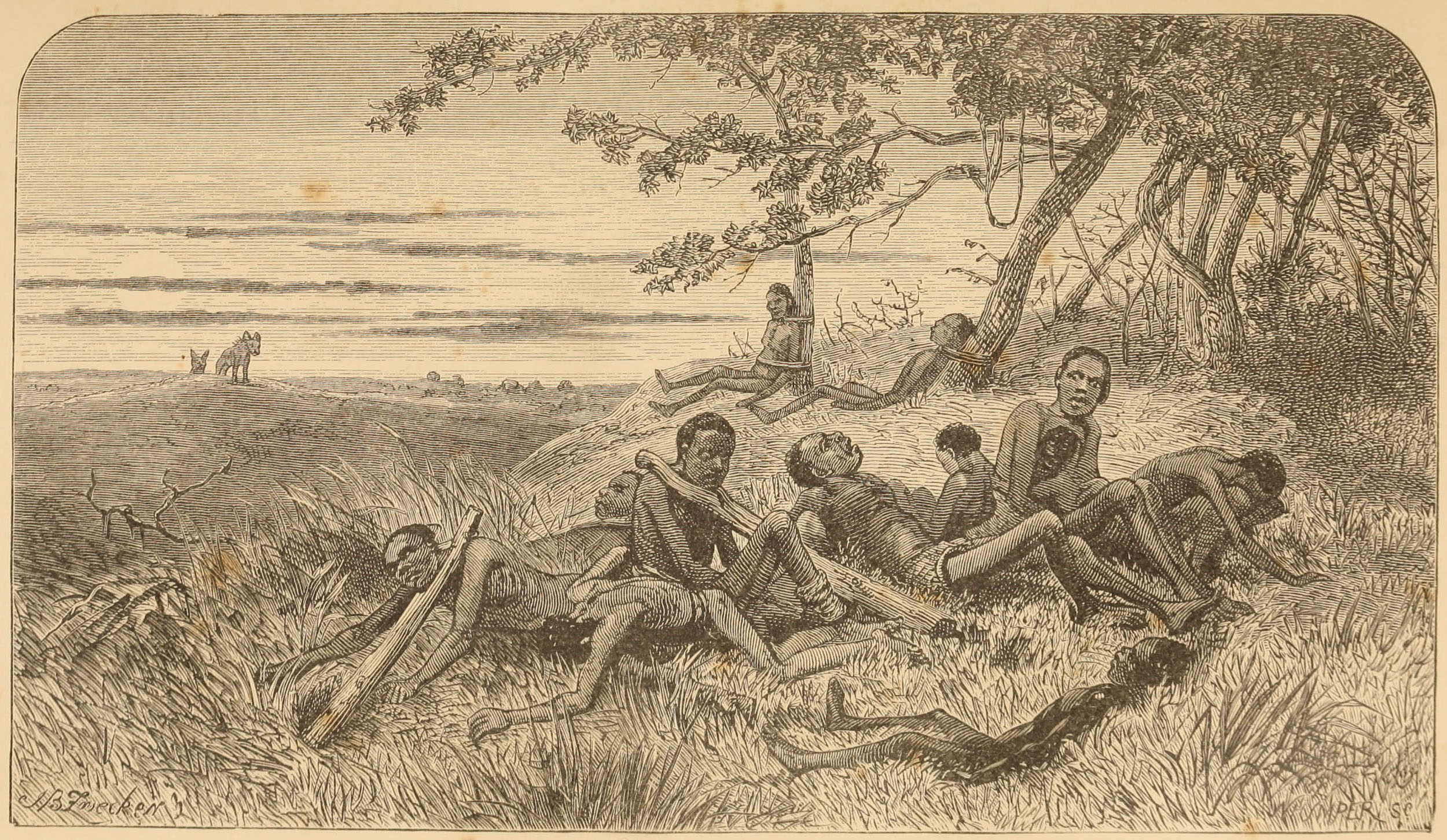

Slaves Abandoned. Illustration from the Last Journals (Livingstone 1874,1:opposite 62). Courtesy of Internet Archive.

This belief troubles his relationship with his porters, many of whom are freed slaves. He divides them into groups: sepoys (Indian soldiers); Nassick boys (educated at a British school for freed slaves in Nashik, India); Johannaese or Johanna men (from the island of Johanna, i.e., present-day Anjouan in the Comoros). Though he is critical of all of them, he is most critical of the Nassick boys for having “the slave spirit pretty strongly,” which he attributes to race: “it goes deepest in those who have the darkest skins” (1866-72:[43]).

Livingstone devotes the end of his career to two goals: finding the source of the Nile and drawing attention to the role Great Britain plays in the African slave trade. In a letter to the Earl of Granville, he writes, “The subject to which I beg to draw your attention is the part which the Banians of Zanzibar who are protected British subjects play in carrying on the slave trade in central Africa and especially in the Manyuema - The country West of Ujiji” (1866-72:[737]). Livingstone argues that because the Banians are British subjects, ending the Zanzibar-based slave trade does not constitute interfering with another nation’s sovereignty. The UJ contains several copied letters in which he exhorts British officials to undertakes this plan in opposition to the idea of slowly “civilizing” the slave trade out of Africa: “there is a sort of charm in the prospect of gradual amelioration of the state of slavery by the steady advance of trade and civilization yet all experience proves the prospect to be delusive” (1866-72:[137]).

| (Left; top in mobile) An image of a page of the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[137]). (Right; bottom) Letter to Henry M. Stanley (Livingstone 1872j:[1]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The page from the journal begins a copy of a letter to the Earl of Clarendon (11 June 1868) that Livingstone marks as "Political / Slave Trade / No. 1." The second image shows a letter to Stanley bearing the same date as Livingstone's prefatory note in the Unyanyembe Journal (14 March 1872, see image above). In it, Livingstone complains of his previous experience in using "slaves in caravans" and advises Stanley to exercise discretion in sending on further such slaves. |

Livingstone’s ideas about race, slavery, and capitalism intersect with his Christian mission, though that intersection is not always straightforward. At certain points he makes clear connections between religious observation and Christianity, on one hand, and the development of European-style culture, on the other. For instance, he complains that “There is nothing interesting in a heathen town” because its inhabitants spend all their time laboring to raise and process food (1866-72:[291]). He also labels Arab and African religions as “superstitions” and argues that we can see the progress of civilization as one of superstition to religion. Demonstrating his belief in progressive development, he adds that even European civilizations show “a remnant of our own superstitions” (1866-72:[370]).

Elsewhere, however, Livingstone questions these mainstream Victorian beliefs, discussing religious practices with the Arab trader Muhmmad Bogarib and noting that “These Arabs seem very religious in their way” (1866-72:[314]). Livingstone also bemoans the unchristian greed that commerce brings by decoupling Christianity and industrial civilization: “If this is enlargement of mind produced by commerce, commend me to the untrading African” (1866-72:[254]). Over the course of the UJ, Livingstone responds to individual situations as they arise, oscillating between belief in and interrogation of Victorian norms.

Ethnographic Observations Top ⤴

The UJ also contains a depth of observations about central and south-central African culture. Livingstone has a few ethnographic questions to which he returns again and again. Almost every time he encounters a new ethnic group, for instance, he records their tattoos; describes their teeth, facial features and/or body type; and speculates on the possibility that they engage in cannibalism. Evidence elsewhere suggests that the local populations in Manyema actually pretended to be cannibals as a strategy of resistance, thereby compelling Livingstone to return to this question time and again, as he writes in a letter to the Earl of Clarendon: “The Manyema are certainly cannibals but it was long ere I could get evidence more positive than would have led a Scotch jury to give a verdict of not proven - they eat only enemies killed in war” (1866-72:[568]) (For more on this topic, see Livingstone, Central Africa, 1870.) The journal also records extensive observations about local religious practices; marriage, sexual practices, and childbirth; technologies (iron forging and tool building); clothing; and what Livingstone’s takes to be the temperament of each ethnic group.

| Images of two pages of the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[88], [213]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The page at left (top in mobile) presents illustrations of the tattoos of the Matambwe ethnic group, which Livingstone has copied over from Field Diary III (Livingstone 1866b:[33], and which would eventually appear in the Last Journals (Livingstone 1874,1:49). Comparison of the three versions, therefore, offers an opportunity to study how such illustrations evolved through successive manuscript stages, not all of which involved Livingstone. The page at right (bottom) combines narrative text regarding the use of a local hammer with an illustration of an individual using the hammer and with a separate illustration of the hammer itself. |

Not surprisingly, Livingstone approves of the body types that he sees as being more European and often connects these bodily features to personal qualities that he finds praise-worthy, including honesty, hard work, and deference to authority (sometimes Livingstone’s perceived authority but also deference to their chief). For instance, he notes of Mapuio’s people, “many have quite the Grecian facial angle – Mapuio has thin lips & quite a European Face – Delicate features and limbs are common & the spur heel as scarce as among Europeans” (1866-72:[204]). Though he does not make a causal connection, he also notes of the same ethnic group, “there is a great deal of good in these poor people” – specifically that they rely on kinship structures, have signs of a solid work ethic, and show what Livingstone deems proper respect for him (1866-72:[204]).

Livingstone also praises non-European cultural forms in relation to how much they conform to his standards. He praises Mapuio’s people for their politeness, communicability, and tendency to separate gender roles; they “have their distinctive tribal tattoo – the women indulge in this painful luxury more than the men probably because they have very few ornaments” (1866-72:[204]). He also records that they use hand clapping to show respect, logging some phrases that can be communicated through clapping: “‘allow me’ – ‘I beg pardon’ – ‘Permit me to pass’ – ‘Thanks’” etc (1866-72:[205]).

Trade Advert for Dr. Livingstone's Last Journals (Murray 1875:14). Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. Horace Waller, Livingstone's posthumous editor, used the Unyanyembe Journal as the principal basis of the published Last Journals (Livingstone 1874).

To Livingstone, these are all signs of a civilized culture; though the expressions differ from European modes of ornament or communication, he sees them as evidence of European values. Livingstone’s interest in authority also shows up as descriptions of many of the chiefs he encounters, though no one garners so much attention as Cazembe, who resides between Lakes Moero and Bangweolo. His violent, autocratic leadership style first garners Livingstone’s censure, but later Livingstone modifies this assessment and concludes that “Cazembe is good but his people are bad” (1866-72:[434]). Livingstone’s own values and experiences thus permeate his record of what he sees around him, often in ways difficult to disentangle.

Trained as a doctor, Livingstone records a significant amount of medical data, including reports of small pox; descriptions of safura or clay eating (what we would now call pica); irritable skin ulcers; syphilis; and malaria. Because his medicines are stolen early in the journey, he often reports on Arab, African, or Portuguese remedies. He also notes many other scientific observations, especially ecological information. He keeps scrupulous rainfall charts, and writes detailed observations of the local plants and growing conditions. He also muses on the relationship between colonialism and animal life: “In other so called new countries a wave of English weeds follows the tide of English Emigration - and so with insects” (1866-72:[81]). Livingstone’s tone varies between descriptions for their own sake and pondering European life in Africa – for instance, by describing geological formations and food cultivation methods at certain points, while at others pointing out the potential presence of coal or lauding the under-used fertility of the soil.

Conflicts Top ⤴

From the beginning of his last journey, Livingstone commits himself to the discovery of the source of the Nile, seeing this as his lasting contribution to geographical knowledge. Unfortunately, he also becomes progressively more convinced that Ptolemy’s theory of the four fountains is correct: “From their bases I found that the springs of the Nile do unquestionably arise - this is just what Ptolemy put down & is true geography” (1866-72:[563]). This erroneous idea, coupled with some incorrect geographical calculations, lead Livingstone to pursue this false idea until his death (see “Livingstone’s Global Sources”).

| Images of two pages of the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[460], [412]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. These two pages present some examples of the many ways that Livingstone uses the Unyanyembe Journal for purposes other than recording dated daily entries. The page at left (top in mobile) contains a "Note on Climate" (the vertical text in the margin is an addition to the main text). The page at right (bottom) includes calculations such as boiling point and height above sea level as recorded by Livingstone at a series of locations in the interior. |

He also becomes more and more embroiled in arguments with the Royal Geographical Society and John Kirk, British political agent at Zanzibar, over money, goods, and porters. Several times, he copies over his requests for more supplies and his justification for these requests. “Let me explain but in no boastful style the mistakes of others who have bravely striven to solve the ancient problem,” he writes in a letter to the Earl of Clarendon in 1871, “and it will be seen that I have cogent reasons for following the painful plodding investigation to its conclusion” (1866-72:[565]).

Though Livingstone lives through and records significant local conflicts, he never ceases to write to a British audience, filtering his experiences through the lens of an eventual British audience. For instance, when his carriers threaten mutiny he dismisses it as “one of the troubles of travelling” (1866-72:[87]). Likewise, when they face starvation, he justifies the days spent recording that: “We all feel weak & easily tired & an incessant hunger teases us, so it is no wonder though so large a space of this paper is occupied by stomach affairs” (1866-72:[252]).

| Images of two pages of the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[557], [628]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. Like many of the final field diaries, the Unyanyembe Journal is actually a co-authored document. The page at left (top in mobile) is the first of fourteen pages in the hand of Henry M. Stanley. Livingstone has marked the page at right (bottom) as "Private / Mem[orandum]," a feature that indicates that Livingstone saw the journal as a work-in-progress and did not intend all of it to reach the public. |

At the same time, the journal contains information that modifies some of the myths later propagated about Livingstone’s last journey, especially in relation to his porters. After James Chuma and Abdullah Susi transported Livingstone’s body and manuscripts from central Africa to Britain, they were lauded as Livingstone’s faithful servants. The UJ, however, records a more autocratic relationship, including an incident when Livingstone, eager to march and finding resistance among his men, “fired a pistol at [Susi] but missed - there being no law nor magistrate higher than myself I would not be thwarted if I could help it” (1866-72:[377]).

These difficulties form a consistent thread throughout the UJ. Livingstone spends months in 1867, for instance, stuck with Hamees’ people south of Lake Tanganyika while he waits to see how a conflict between the Nsama (alternately, Insama) people and the Arabs plays out. This dictates the route he will take and who will go with him (see 1866-27:[342] for a single narrative account). His men mutiny over the course of 1870-1 and as a result, he cannot hire canoes or guides. He travels with Arab slave traders and between their bad reputation and his own, he is constantly stymied in his travels and often in open conflict with locals. Often, local events collide with outside politics, as when a horrific massacre in 1871 at Nyangwe by Arab traders combine with new porters of whom he does not approve (1866-72:[698]; cf. our edition of Livingstone’s 1871 Field Diary).

Conclusions Top ⤴

Overall, the UJ combines Livingstone’s daily observations and events with his attempts to see these events as a whole and present them for a British audience. His rationale for this journey emerges as a combination of personal ambition, moral reasoning, and a nationalist civic duty. When asked why he is there, he tells a Babsia traveller:

I wished to make country and people better known to the rest of the world - We were all children of one father and I was anxious that we should know each other better and that friendly visits should be made in safety - Told him what the queen [Victoria] had done to encourage the growth of cotton on the Zambezi and how we had been thwarted by slave traders and their abettors - they were pleased with this. (1866-72:[447])

As this shows, Livingstone’s core beliefs in Christianity, monarchy, and development drove his presence in Africa, where he believed himself to be aiding the people of Africa through greater publicity. The controversies and conflicting loyalties that he records in the Unyanyembe Journal do not substantially alter his belief. Though he spent most of his adult life living in Africa, Livingstone clung fiercely to his identity as a British subject, as this – the most comprehensive and polished manuscript from his last journey – attests.

![John Murray III and Anon., David Livingstone - Boat Scene (Painted Magic Lantern Slide), [1857], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND. John Murray III and Anon., David Livingstone - Boat Scene (Painted Magic Lantern Slide), [1857], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND.](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_014067_0001-carousel.jpg)

![Image of two pages from Livingstone's Field Diary XVI (Livingstone 1872h:[2]-[3]). CC BY-NC 3.0 Image of two pages from Livingstone's Field Diary XVI (Livingstone 1872h:[2]-[3]). CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000016_0003-carousel.jpg)

![David Livingstone, Map of Lakes Nyassa and Shirwa [1864?], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND; Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson, CC BY-NC 3.0 David Livingstone, Map of Lakes Nyassa and Shirwa [1864?], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND; Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson, CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000077_0001-tile.jpg)

![An image of a page of the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[1]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[1]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/the-unyanyembe-journal-overview/liv_000019_0001-article.jpg)

![An image of a page of the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[7]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[7]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/the-unyanyembe-journal-overview/liv_000019_0007-article.jpg)

![An image of a page of the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[296]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[296]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/the-unyanyembe-journal-overview/liv_000019_0296-article.jpg)

![An image of the spine of the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[775]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of the spine of the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[775]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/the-unyanyembe-journal-overview/liv_000019_0775-article.jpg)

![An image of the fore edge of the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[776]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of the fore edge of the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[776]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/the-unyanyembe-journal-overview/liv_000019_0776-article.jpg)

![An image of a page of the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[137]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[137]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/the-unyanyembe-journal-overview/liv_000019_0137-article.jpg)

![Letter to Henry M. Stanley (Livingstone 1872j:[1]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). Letter to Henry M. Stanley (Livingstone 1872j:[1]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/the-unyanyembe-journal-overview/liv_000048_0001-article.jpg)

![An image of a page of the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[88]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[88]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/the-unyanyembe-journal-overview/liv_000019_0088-article.jpg)

![An image of a page of the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[213]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[213]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/the-unyanyembe-journal-overview/liv_000019_0213-article.jpg)

![An image of a page of the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[460]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[460]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/the-unyanyembe-journal-overview/liv_000019_0460-article.jpg)

![An image of a page of the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[412]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[412]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/the-unyanyembe-journal-overview/liv_000019_0412-article.jpg)

![An image of a page of the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[557]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[557]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/the-unyanyembe-journal-overview/liv_000019_0557-article.jpg)

![An image of a page of the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[628]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[628]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/the-unyanyembe-journal-overview/liv_000019_0628-article.jpg)