Livingstone’s Life & Expeditions

Cite page (MLA): Livingstone, Justin D. "Livingstone’s Life & Expeditions." Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, eds. Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. University of Maryland Libraries, 2015. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/76ab1aa0-2bf4-4c42-adf7-c8c4ee960236.

This essay overviews Livingstone’s life and expeditions. It presents an account of his upbringing in Scotland, his early years as a missionary in southern Africa, and the celebrated cross-continental expedition of 1852-56. The essay also discusses the Zambezi Expedition (1857-64) as well as Livingstone’s final journeys (1866-73), including the 1871 Nyangwe massacre and the famous meeting with Henry M. Stanley ("Dr Livingstone I Presume?"). The essay closes with an account of Livingstone’s death (1873), followed by the transcontinental transportation of his remains to Britain and his interment at Westminster Abbey (1874).

- Early Years

- Education and Intellectual Formation

- Early Travels (1841-52)

- Crossing the Continent (1852-56)

- Return to Britain (1856-58): The Publication of Missionary Travels

- The Zambezi Expedition (1858-64)

- Second Return to Britain (1864-65)

- Final Journeys (1866-68): The Nile Question

- Final Journeys (1869-72): Nyangwe Massacre and the Encounter with Stanley

- Livingstone’s Death and Burial (1872-73)

- Acknowledgements

- Works Cited

Early Years Top ⤴

David Livingstone, perhaps the best known missionary and explorer of the Victorian period, was born in 1813 to parents Neil and Agnes Livingstone. He began life in Blantyre, a small town near Glasgow on the river Clyde where the cotton mill was the major employer. Like many locals, Livingstone entered the factory when he was ten years old, working as a piecer with the job of repairing threads broken during cotton spinning.

Though Livingstone’s childhood has often been romanticized, conditions at the Blantyre Mill were severe. Run by Monteith, Bogle and Co., work began at 6am and continued until 8pm with 40 minutes for breakfast and 45 for dinner (Mullen 2013:19). The mill had among the longest working hours in Scotland and, moreover, employed a greater number of children than most others operating in the greater Glasgow area. Livingstone was part of a considerable “child labour force” at work in the industry (Mullen 2013:19).

Photograph of Shuttle Cottages, Blantyre. Copyright David Livingstone Centre. May not be reproduced without the express written consent of the National Trust for Scotland, on behalf of the Scottish National Memorial to David Livingstone Trust (David Livingstone Centre).

The mill, however, did pay better than many and while there was considerable overcrowding in the local Shuttle Row tenements, housing was superior than it was in central Glasgow. The owners also helped to fund the salary of the local Church of Scotland clergyman and provided education by supporting a school, which some – like Livingstone – were able to use to their advantage (Mullen 2013:21-22).

Education and Intellectual Formation Top ⤴

When he was 19, Livingstone had saved enough money to begin medical training at Anderson’s college in Glasgow. Following the example of Karl Gützlaff, he hoped to combine medicine and missionary endeavour as an overseas agent (Jeal 2013:14). Certainly, for parts of his career Livingstone functioned as an early medical missionary: although much work remains to be done on his medical contributions, Livingstone’s insights into febrile conditions and his emphasis on prophylactic medication are considered to be important interventions in the comprehension and treatment of malaria, Human African trypanosomiasis, and various other tropical diseases (Lawrence 2010b).

Moreover, what’s interesting about Livingstone’s medical practice is how remarkably varied it was, ranging across “obstetrics, ophthalmology, the removal of tumours, tuberculosis, and the treatment of venereal diseases” (Harrison 2013:73). While this was due to some extent to the demands of the situations he found himself working in, his approach also reveals the Scottish character of his medical education: it demonstrates the “progressive and practical use of a Scottish training that combined the roles of physician and surgeon,” careers which were still differentiated in the English system in the 1830s (Harrison 2013:73).

Livingstone's pocket surgical instrument case. Copyright Livingstone Online (Gary Li, photographer). May not be reproduced without the express written consent of the National Trust for Scotland, on behalf of the Scottish National Memorial to David Livingstone Trust (David Livingstone Centre).

Indeed, it is important to recognise that Livingstone was shaped by a Scottish intellectual tradition, which he encountered in Glasgow and in his earlier reading. Like many Scottish missionaries of the nineteenth century, Livingstone was influenced “not simply by evangelical Christianity, but also by the intellectual milieu of the later Scottish Enlightenment” (Stanley 2014:157).

For instance, Livingstone was impressed as a youth by the philosopher and science writer, Thomas Dick, whose popular theological works enabled him to conclude “that religion and science are not hostile, but friendly to each other” (Livingstone 1857b:4). Dick’s understanding of scientific observation as an examination of divine revelation in nature undoubtedly impacted Livingstone’s later enthusiastic work as a field-naturalist (Astore 2004).

Furthermore, the “post-Enlightenment” environment – in which “Christian orthodoxy of a broadly Calvinistic kind” was combined “with an unequivocal commitment to empirical science” – influenced the cultural encounters that resulted from his missionary work and exploration (Stanley 2014:157). While Livingstone often concluded that various tribal practices were based on mistaken beliefs, the rigorous “scientific methodology” that he inherited led him to produce detailed examinations of tribal beliefs and customs, and to attempt to locate them in their local context.

Early Travels (1841-52) Top ⤴

In 1838 Livingstone joined the London Missionary Society (LMS), a predominantly congregationalist organisation. He would later claim that it was the society’s non-denominational and “perfectly unsectarian character” that appealed to him (Livingstone 1857b:6). Following theological training in Chipping Ongar, Essex, and further medical studies in London, Livingstone was ready to enter the mission field.

He initially intended to go to China, but was prevented from doing so by the outbreak of the Opium Wars in 1839. Instead, he changed course to South Africa, having been enticed by the words of the celebrated missionary, Robert Moffat, who described the “smoke of a thousand villages” yet to be visited (Blaikie 1880:28).

In 1841, Livingstone arrived in South Africa where he would spend eleven years at various inland stations, chiefly as missionary to the BaKwena under the leadership of Sechele. Sechele later became an influential figure in the Christianisation of southern Africa, seeking to reconcile the new religion with various traditional practices and beliefs (Parsons 1998:39-40).

David Livingstone - Lake Ngami (Painted Magic Lantern Slide), c.1857. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland |

During his time with the BaKwena, Livingstone began to make journeys to the north, partly to improve his skills in the Setswana language and partly to look for sites for new mission stations. Enticed by tales of a lake in the interior and fuelled by a desire to reach Sebituane, the chief of the Makololo, Livingstone aspired to cross the Kalahari Desert. In 1849, with the help of William Cotton Oswell, he succeeded in doing so and made it to the shore of Lake Ngami. He would later receive a reward from the Royal Geographical Society (RGS) for this achievement.

Livingstone was increasingly entertaining the hope of opening the continent to the outside world, by finding a possible “highway” to the coast (Schapera 1961:131-138). Learning about a major river to the North, the Zambezi, he hoped it might provide a “key to the Interior” (Schapera 1961:139-140; Roberts 2004). With Oswell, Livingstone reached the river in August 1851 and felt confirmed that this was the very highway he was looking for.

Crossing the Continent (1852-56) Top ⤴

It was at this point that Livingstone’s travels started in earnest. In 1852, he sent his family back to Britain so that he could embark on a serious exploration of the Zambezi. This expedition was undertaken in collaboration with the new chief of the Makololo, Sekeletu, the son of Sebituane. He agreed to supply Livingstone with goods in order to pioneer a trade route to Loanda, in Angola, on the west coast.

Undoubtedly, Livingstone’s journey was aided by his status as an “nduna” of Sekeletu, one whose authority came from a powerful chief (Ross 2002:89, 94). Moreover, Livingstone was very reliant on his African retinue as interpreters in regions that did not speak Setswana. While exploration has frequently been discussed as the endeavour of heroic individuals, in reality explorers were reliant on such “intermediaries” whose linguistic skills and local knowledge were essential to the success of European expeditions (Driver and Jones 2009:11; Kennedy 2013:163).

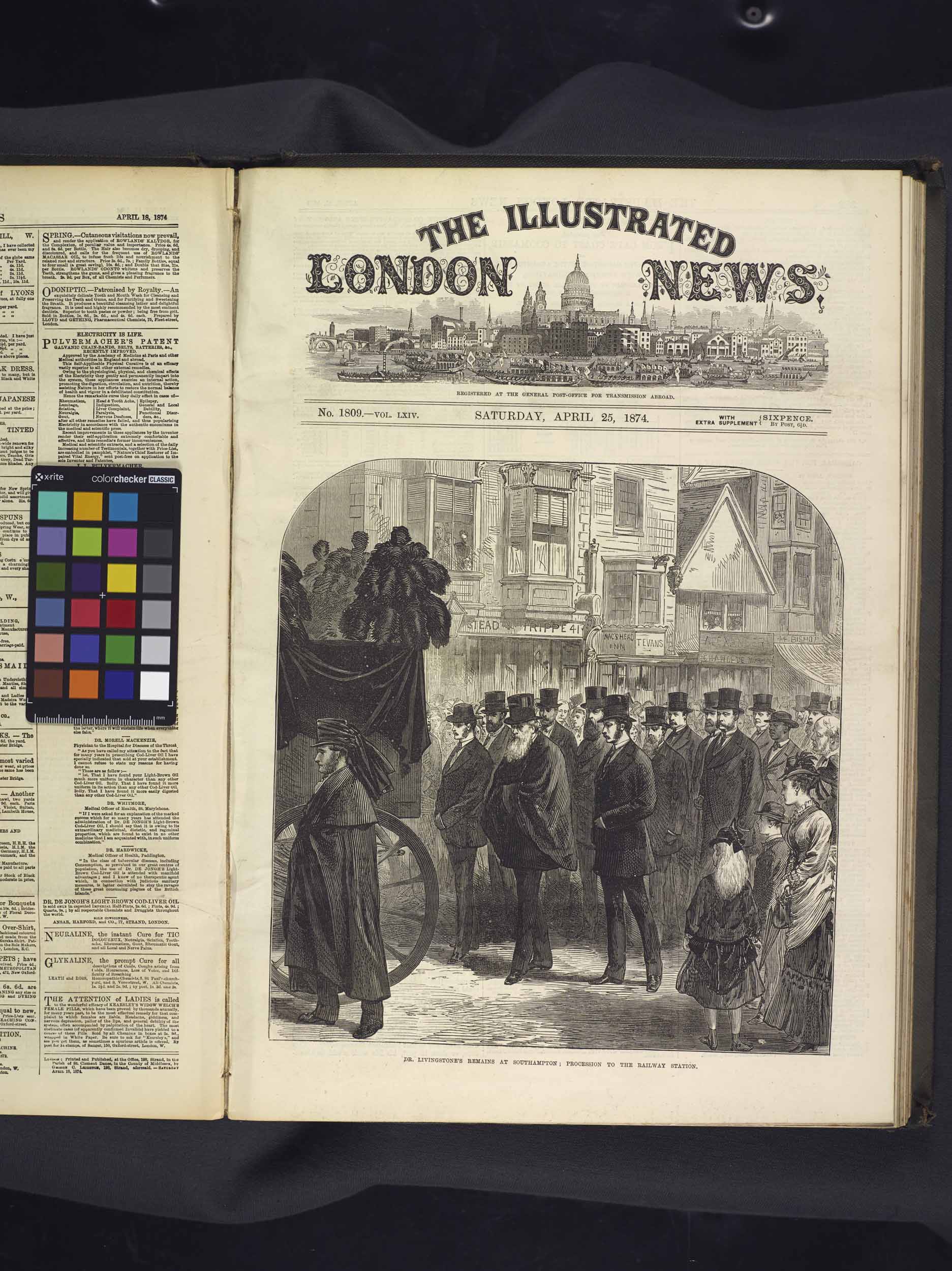

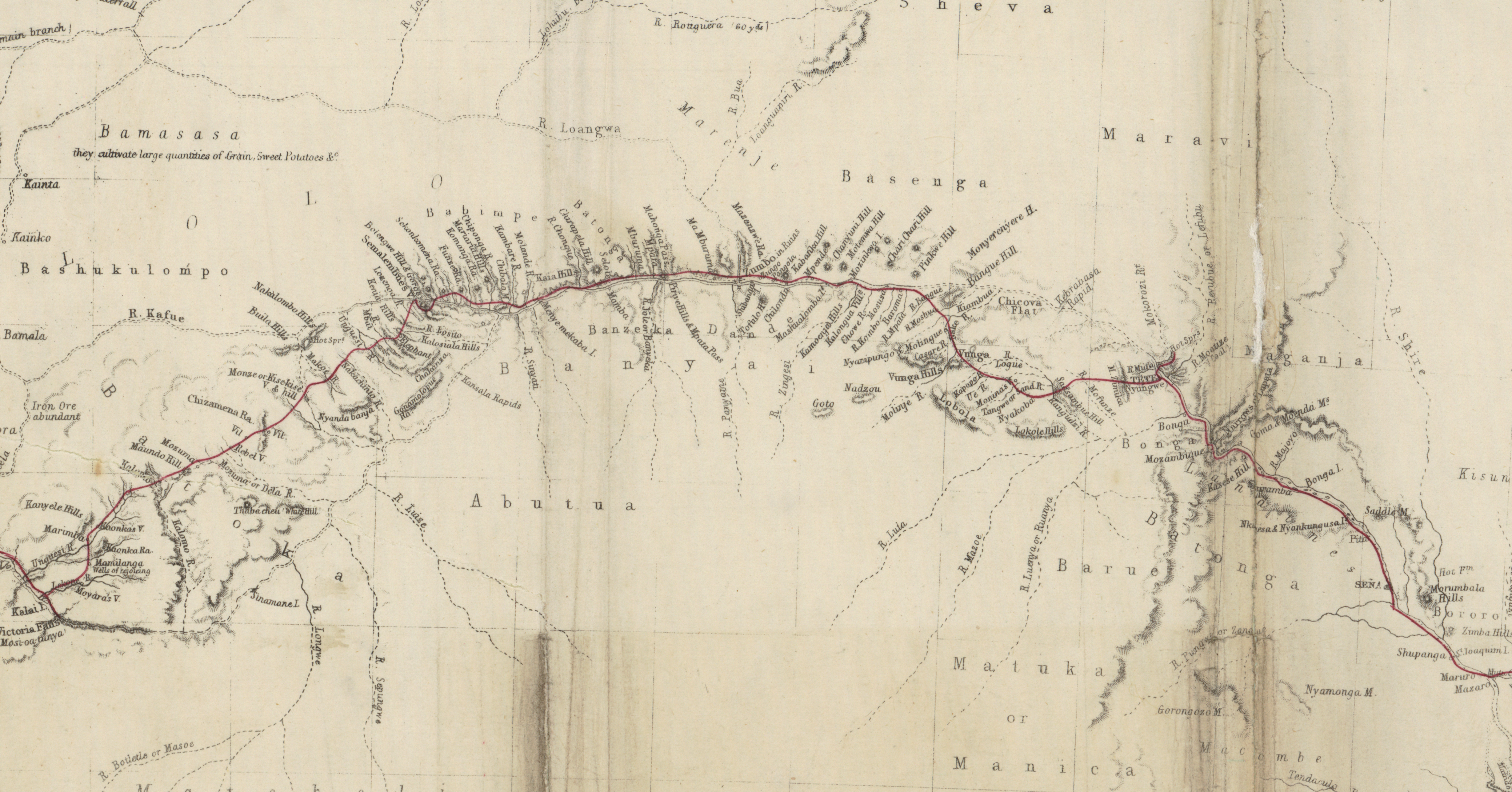

Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa, Map, 1857. This map traces the route of Livingstone’s travels from 1849-56. The segment selected here shows Linyanti, the village that served as the base for his cross-continental expedition of 1852-56. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland

With his company of Kololo companions, Livingstone reached Loanda in May 1854 following a difficult journey that cost him all his trade goods. Although ill and exhausted, he refused to return to Britain. Dissatisfied with the route he had travelled, Livingstone resolved instead to determine if passage to the east coast would be more accessible. So he set out again, on a journey that would take him across the entire continent.

Returning first to Linyanti, Sekeletu once more decided to support Livingstone and equipped him with men and ivory for the journey. Shortly after embarking, his guides led him to the waterfall known locally in the Lozi language as “Mosi-oa-Tunya,” or “the smoke that thunders,” which he renamed Victoria Falls. During this expedition, Livingstone was fated to miss the Cabora Bassa rapids, which would later foil his plans to use the Zambezi as a highway to the interior. In March 1856, he arrived in Tete and proceeded to Quelimane on the Mozambique coast in May.

He was soon hailed as the first European to have ever crossed the entirety of Africa. While his achievement was considerable, the continent had, however, previously been traversed by Arab and African traders who followed a long pre-established network of transregional caravan routes. It was this spatial infrastructure that that would facilitate the later travels of the Europeans involved in continental exploration (Rockel 2014:172).

Return to Britain (1856-58): The Publication of Missionary Travels Top ⤴

On his return to Britain, Livingstone was presented with the gold medal of the Royal Geographical Society in recognition of his expedition. With his newfound fame, he also found himself pressed upon to write an account of his time in Africa. It was of course common for missionaries to produce narratives of their years overseas; in Victorian Britain missionary writing was an established and popular literary genre. Livingstone was thus urged to follow in the footsteps of his predecessors in the London Missionary Society, such as John Williams and Robert Moffat, who each wrote substantial volumes (Wingfield 2013:118).

Manuscript of Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa (Part I), January-October 1857, by David Livingstone. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland |

Yet, to some extent Livingstone broke with LMS convention when he chose to publish with John Murray, a specialist not in missionary writing but in travel literature. Murray had been very keen to secure Livingstone’s account of his cross-continental expedition and eagerly offered him generous terms. He promised him an advance of 2000 guineas and “two thirds of the profits of every Edition” (Murray 1857a, also 1857b).

The book was expected to be a sensation and it certainly was: the first impression of 12,000 copies sold out prior to publication in November 1857 and a second impression of 30,000 soon followed. For the first time in his life, Livingstone was wealthy: the sales made him over £8,500 (Roberts 2004).

While Missionary Travels was written at speed, the book was a truly impressive achievement. As a hybrid text – missionary narrative, travelogue, and work of field science – it had considerable breadth and substantial appeal. In contrast to many other explorers, moreover, Livingstone’s descriptions of Africans were strikingly sympathetic.

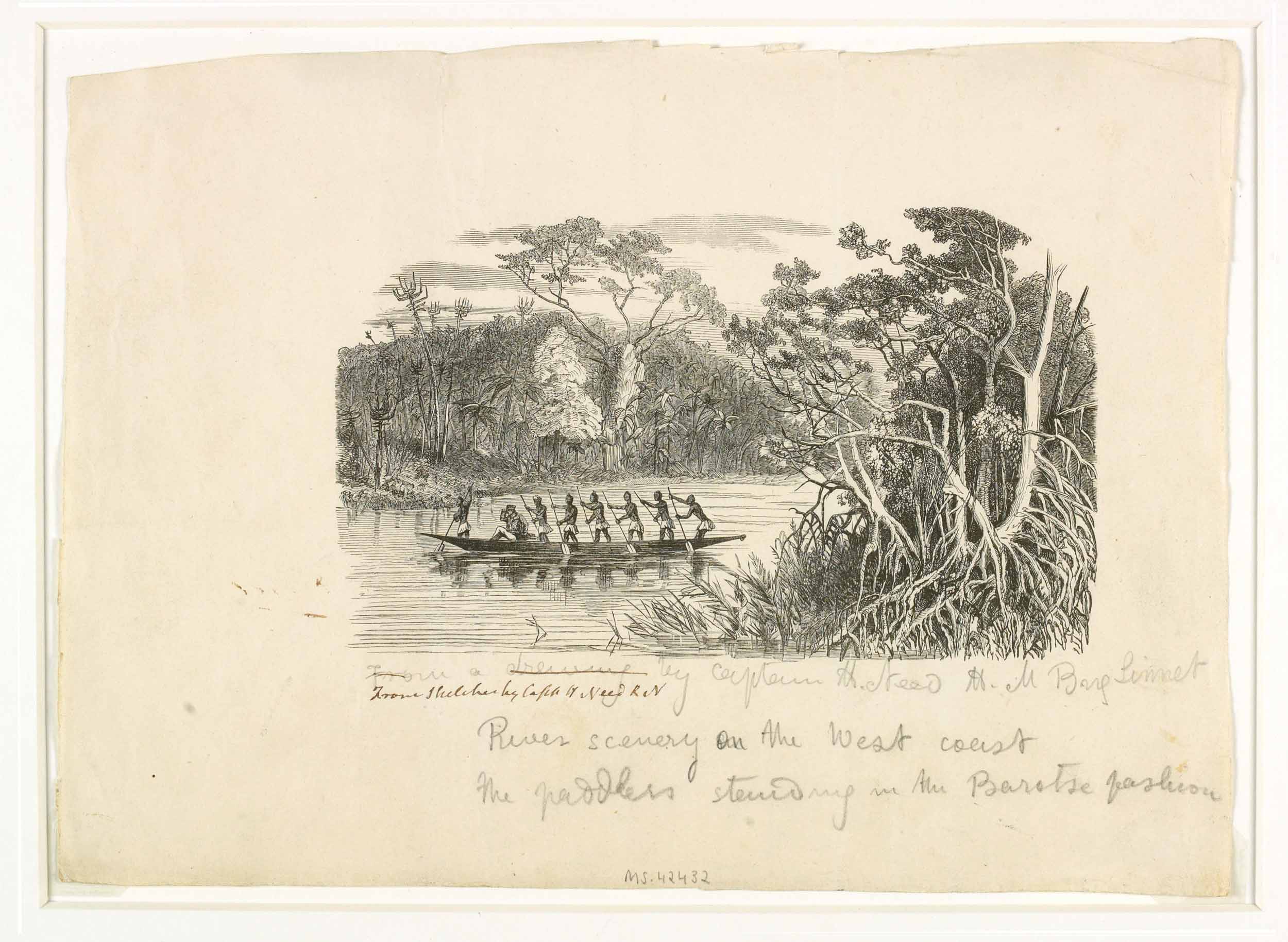

River Scenery on the West Coast (David Livingstone's Annotated Proof), c.1856-1857. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland

In writing his book, Livingstone’s primary aim was to direct public attention to central and southern Africa, which he presented optimistically as an “inviting field” for mission work and trade (Wisnicki 2009:257). It offered him the chance to advocate a combination of Christianity, commerce and civilisation and to encourage British intervention in the continent. Undoubtedly Livingstone’s attractive, almost “utopian” vision and his major literary success, contributed to his fame and his lasting reputation (Holmes 1993:351).

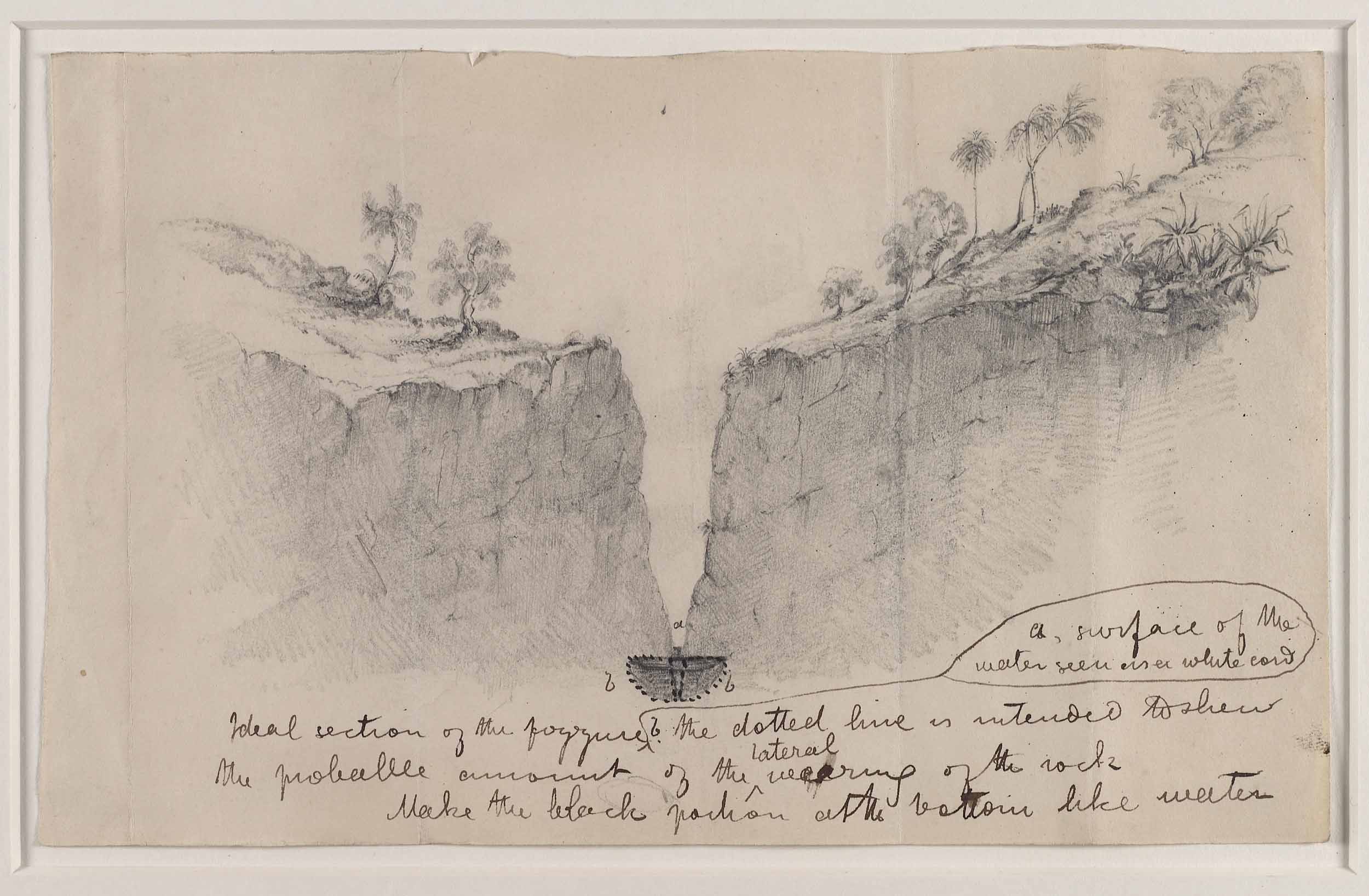

Missionary Travels was a good investment for John Murray. He secured one of the best-selling travel books of the age. Yet Livingstone was not always the easiest author to work with. When it came to illustrating the book, his frequent requests for minor alterations frustrated Joseph Wolf, the artist whom Murray assigned to the publication (Koivunen 2001:6). Livingstone also resented editorial intrusion, complaining to his publisher about the interference of one editor whose changes threatened to “emasculate” his writing. He would, Livingstone told Murray, tolerate no sign of “namby pambyism” (Livingstone 1857a).

Ideal Section of the Fizzure (David Livingstone's Annotated Proof), c.1856-1857. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland

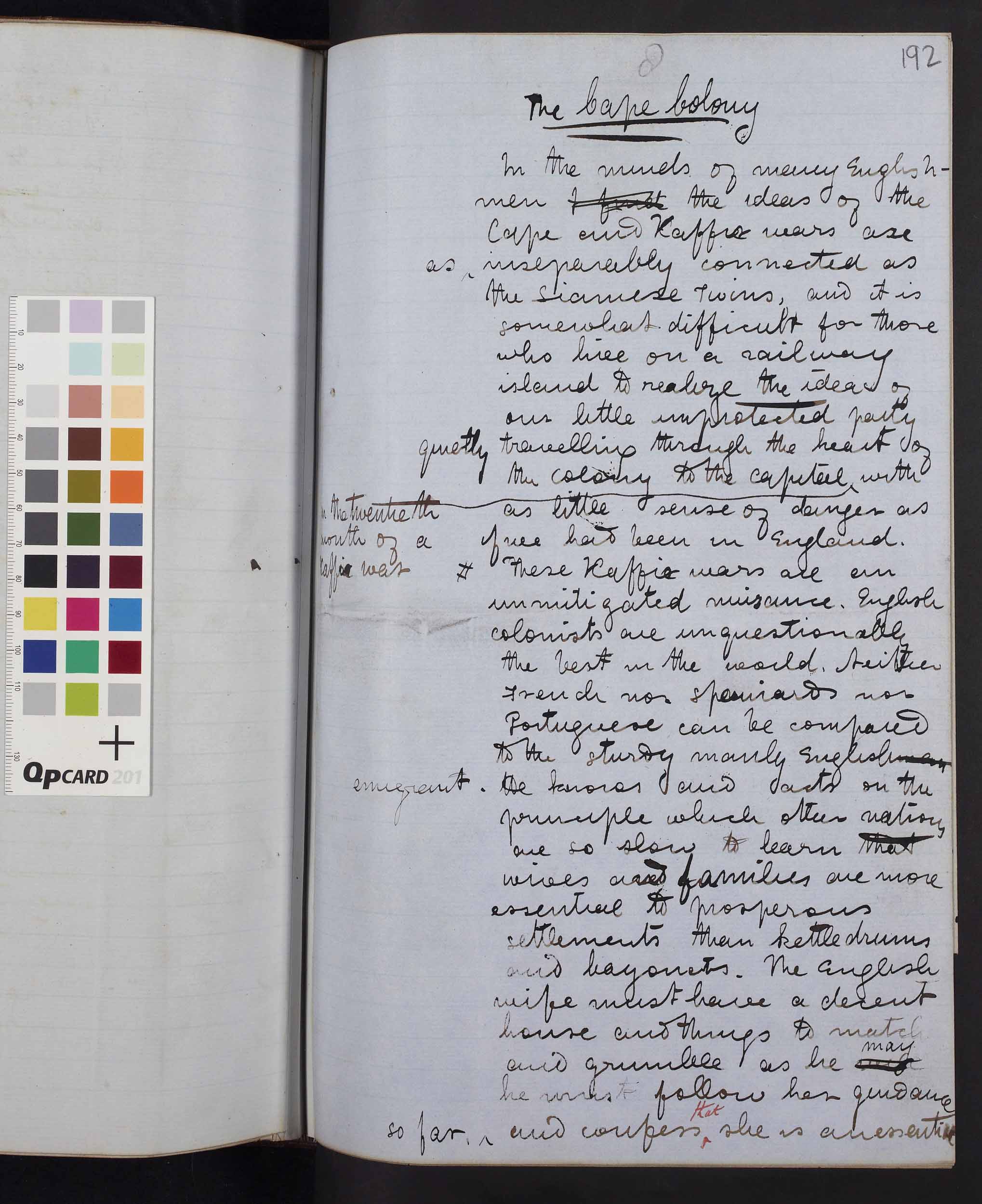

Missionary Travels is also interesting for what it leaves out. In the original handwritten manuscript of the book, for instance, Livingstone had included a substantial critique of the Cape Frontier Wars, in which he criticised colonial violence at length. Perhaps in fear of alienating the establishment, or perhaps at Murray’s prompting, this passage – running to almost thirty pages – is excluded from the published text (Livingstone 2011; Livingstone 2014).

While at home, Livingstone was in demand as a guest speaker. He was not only a celebrated missionary and geographer: he was also now a celebrity. Although he found public speaking difficult, he gave numerous addresses about his work and future plans, notably at the British Association for the Advancement of Science in Dublin and at the University of Cambridge. He received honorary degrees from the Universities of Oxford and Glasgow, and was elected to the Royal Society.

The Zambezi Expedition (1858-64) Top ⤴

In March 1858, after fifteen months in Britain, Livingstone again set sail for Africa. While home, he had relentlessly emphasised the commercial possibilities of the continent and the potential for “legitimate commerce” to combat slavery (Livingstone 1857b:92). Now a celebrated national hero, Livingstone received substantial support for his plans. Financial backing for his next expedition was soon raised by public subscription and he was also awarded a sum of £5000 from the British government. Having now parted ways with the London Missionary Society, Livingstone returned to Africa as a British consul, leading a team of six Europeans with a mandate to evaluate the possibilities for British trade on the Zambezi (Roberts 2004).

The original plan was to reach the Zambezi delta, travel to the Batoka highlands, and from there explore the area and catalogue its natural resources (Dritsas 2010:11). The expedition, however, faced difficulties from the start. Relations among the group were strained, in part due to Livingstone’s shortcomings as a leader: several members either resigned from the expedition or found themselves dismissed. After investing such hopes in the Zambezi, there was considerable disappointment when further investigation of the Cabora Bassa rapids proved them to be impassable.

![The Pioneer at Anchor in Pomony Harbor, Johanna. Livingstone and Kirk Were on Board and They Were about to Start for the Rovooma River to Ascertain if It Communicated with Lake Nyassa in Central Africa. 3 Sep[tember]. [18]62, by Thomas Mitchell. Courtesy of the Smithsonian Libraries, Washington, D.C. The Pioneer at Anchor in Pomony Harbor, Johanna. Livingstone and Kirk Were on Board and They Were about to Start for the Rovooma River to Ascertain if It Communicated with Lake Nyassa in Central Africa. 3 Sep[tember]. [18]62, by Thomas Mitchell. Courtesy of the Smithsonian Libraries, Washington, D.C.](/sites/default/files/life-and-times/livingstone-s-life-expeditions/liv_012014_0001-crop-article.jpg)

"The Pioneer at Anchor in Pomony Harbor, Johanna. Livingstone and Kirk Were on Board and They Were about to Start for the Rovooma River to Ascertain if It Communicated with Lake Nyassa in Central Africa. 3 Sep[tember]. [18]62," by Thomas Mitchell. Courtesy of the Smithsonian Libraries, Washington, D.C.

The whole expedition had rested on the navigability of the river, and so Livingstone was forced to consider other areas in the search for his highway to the interior. Now, his attention would fall on the Shire River, Lake Nyassa, and the Rovuma. Even though the original plans had proven unworkable, the government permitted the expedition to be extended beyond the original two years that had originally been approved.

Throughout the expedition, navigation was never easy. The water was often too low to permit passage, and Livingstone felt that his problems stemmed from steamboats that were poorly designed. The expedition also faced difficulties from other quarters. The encroachment of slave raiders into the Shire highlands and inter-tribal conflict created an increasingly unstable environment (Roberts 2004; Dritsas 2010:3). While Livingstone managed to explore a considerable portion of Lake Nyassa, which he called the “lake of stars” (Ross 2002:143), these conditions prevented him from ever reaching its northern end. The failure to circumnavigate and fully survey the lake was a major disappointment to British geographers (Dritsas 2010:17).

At the same time, Livingstone’s hopes for a mission in central Africa were frustrated. Inspired by the emotive lectures that he gave in Britain, the Universities’ Mission to Central Africa (UMCA) had sent a party to establish a mission in 1861. While not directly connected to the expedition, they looked to Livingstone for support and advice. They eventually settled in Magomero, a Manganja village in the Shire highlands.

However, the mission became embroiled in tumultuous local politics (Roberts 2004). Many of the members also suffered from illness and died of fever. Following the death of the mission’s leader, Bishop Charles Mackenzie, the mission was withdrawn much to Livingstone’s disappointment. Likewise, a mission to the Makololo sent out by the LMS at Livingstone’s encouragement also ended in disaster and the deaths of almost the entire party.

Manuscript of Footnote to Page 600: Addition to Narrative of an Expedition to the Zambezi and its Tributaries, 1864-1865, by Charles Livingstone and David Livingstone. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland |

The tragedy during the expedition, moreover, was personal for Livingstone. His wife, Mary, had come out to join him in 1862, but died shortly afterwards at Shupanga. In July 1863, the expedition was recalled to Britain. After a short excursion to the area west of Lake Nyassa, Livingstone began to return home. In a daring journey, he sailed his boat, the Lady Nyassa, across the Indian Ocean to Bombay, before boarding a ship to Britain.

In light of the many difficulties, it is no surprise that the Zambezi Expedition has often been deemed a failure: it certainly failed to meet the tremendous expectations of many supporters at home. Yet this reputation has obscured the fact as a scientific expedition – understood as “an aggregate of projects” with a range of objectives and aspirations – it had some profitable results and various important botanical and zoological specimens were returned to Kew Gardens and the Natural History Museum (Dritsas 2010:3, 24, 34).

Second Return to Britain (1864-65) Top ⤴

When Livingstone returned to Britain, his reception was more subdued than it had been in 1856-8. Some supporters had become disillusioned and this was compounded by the vocal criticisms of several members of the expedition. The decline in Livingstone’s reputation, however, has sometimes been overstated. Livingstone remained in the public eye and actually continued to be largely well received (MacKenzie 2013:283). On a visit to Inverary in 1864, for instance, at the invitation of the Duke of Argyll, he experienced a particularly enthusiastic welcome by the local community (Ross 2005:95).

Nevertheless, in A Narrative of an Expedition to the Zambesi (1865), the book Livingstone co-wrote with his brother Charles, he clearly set out to defend his reputation. He certainly aimed to deflect the criticism he had received over the deaths of the LMS and UMCA missionaries. With accusations that he had neglected the UMCA mission circulating, for instance, Livingstone made sure to emphasise that although it was "entirely distinct" from his own expedition, he had felt "anxious to aid our countrymen in their noble enterprise" and had made it his duty to ensure the party was settled safely (Livingstone and Livingstone 1865:350).

Moreover, since he had been accused of embroiling Mackenzie in local conflicts, Livingstone felt obliged to insist that he had warned the Bishop not to "interfere in native quarrels": while Livingstone had sympathy with Mackenzie’s actions, he was keen to point out that unwarranted "blame was thrown on Dr. Livingstone’s shoulders, as if the Missionaries had no individual responsibility for their subsequent conduct" (Livingstone and Livingstone 1865:363). However, although the book served as a "vindication of Livingstone’s leadership" (Clendennen 1989:34; Martelli 1970:237), it was chiefly designed as a manifesto to mobilise and intensify British opposition to the slave trade.

Carte de Visit, Portrait of David Livingstone, by P.E. Chappuis. Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Libraries, Washington, D.C. |

While in Britain, Livingstone also used his time to lay plans for his return to Africa. This time, at the prompting of Roderick Murchison, the President of the RGS, he was to examine the water system of central Africa by exploring the terrain between Lake Nyassa and Lake Tanganyika (Wisnicki 2017). The hope was also that he might finally settle the age-old question of the source of the Nile, proving others like John Hanning Speke to be incorrect.

Nonetheless, he still viewed himself as a missionary. He had an extended concept of the missionary enterprise, and the expedition offered him the chance to continue using exploration to try and advance Christianity, commerce and civilisation, and bring about the end of the slave trade (Wisnicki 2017).

Final Journeys (1866-68): The Nile Question Top ⤴

Livingstone was now appointed “Roving Consul” in central Africa, a title that came with no salary. Financial support from the government was limited for this new plan: only £500 was forthcoming. His old university friend James “Paraffin” Young, however, provided much needed assistance by contributing £1000. As a result, Livingstone had some financial backing, but its limited extent ensured that the venture would be on a much smaller scale this time.

In contrast to the previous expedition, on this occasion Livingstone would not be accompanied by other Europeans. In Bombay he recruited a number of Africans from mission schools as well as a contingent of sepoys. In Zanzibar he added to his retinue by recruiting an additional ten “Johanna men,” his name for porters from the Comoro Islands working in east Africa (Ross 2002:260). Only five from this original group would remain throughout the duration of his travels.

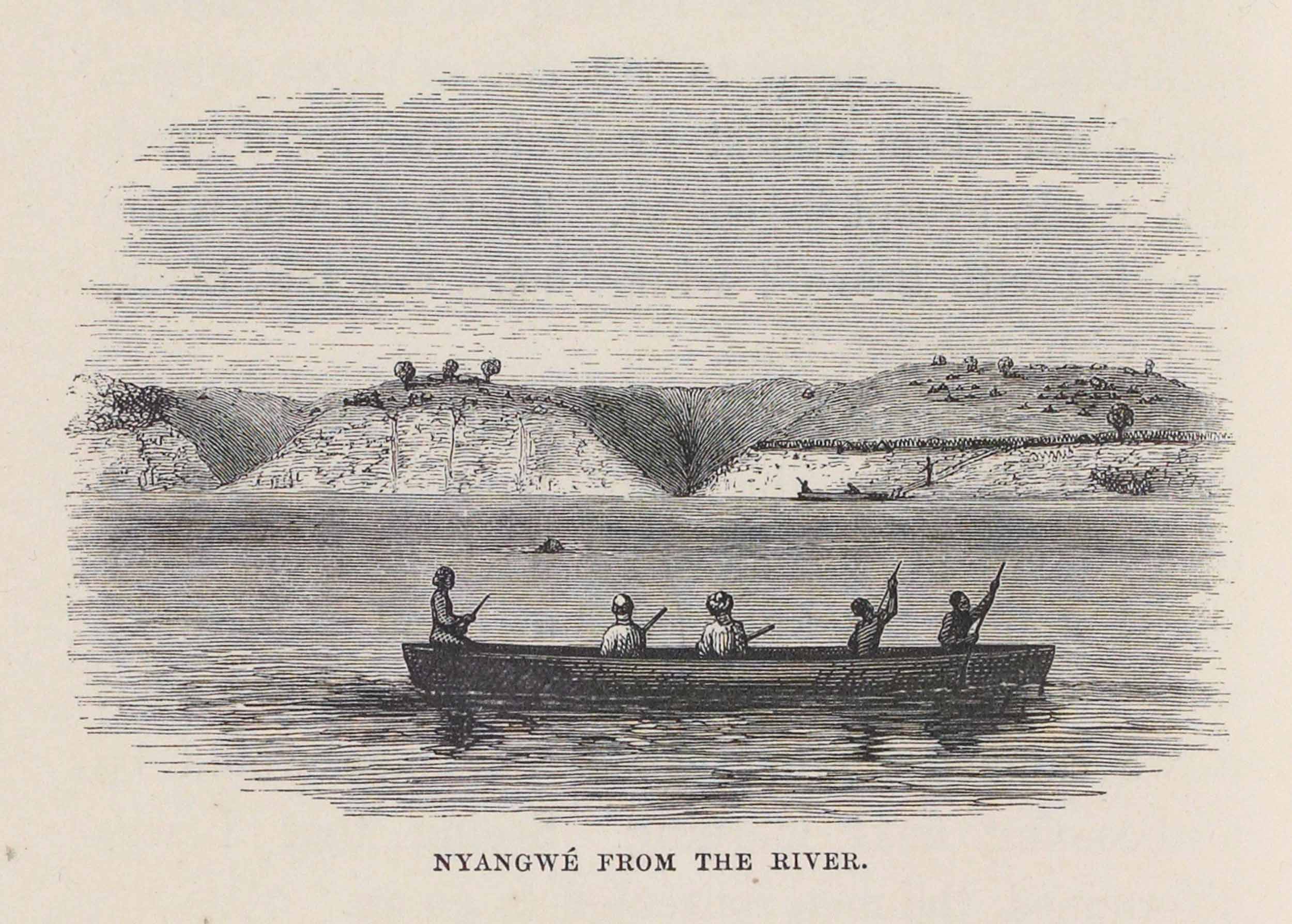

"Nyangwe from the River" from Verney Lovett Cameron's Across Africa (1877,1:378). Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland

Livingstone’s final journeys lasted seven years, during which he passed through vast regions of east and central Africa, which would today include Mozambique, Tanzania, Malawi, Zambia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Wisnicki 2017). Early in 1867, his chronometers were damaged which led to subsequent errors in his longitudinal observations. He also struggled with depleted medical supplies, local wars, and the challenge of securing goods from Zanzibar.

Thanks to his travels, he developed a complex theory of the central African river system, arguing for three “lines of drainage” that connected to the Nile (Wisnicki 2017; Jeal 2013:323). In order to prove his theory, which was ultimately incorrect, he set his eyes on the Lualaba river which he thought might feed the Nile. He feared, however, as was indeed the case, that it was really part of the Congo.

Final Journeys (1869-72): Nyangwe Massacre and the Encounter with Stanley Top ⤴

In July 1869, Livingstone set out from Ujiji, a trading depot on Lake Tanganyika with the goal of reaching and tracing the Lualaba. After an arduous journey that lasted until March 1871, he reached the bank of the river at a village called Nyangwe. Prevented from securing canoes to explore the river, Livingstone remained there for several months. While he enjoyed visiting the market regularly and questioning the locals about the surrounding geography, the inability to travel further proved a frustrating experience.

It is important to note that in Livingstone’s "last journeys," from 1866, he had been extremely reliant on the assistance of Arab-Swahili traders. The extent of the pre-existent trade network ensured encounters with their caravans, while regular illness and a lack of supplies often rendered him dependent on their goodwill. Although a committed abolitionist, Livingstone actually developed good relationships with a number of traders – notably travelling with one of the most celebrated and infamous Zanzibaris, Tippu Tip (Ross 2002:209).

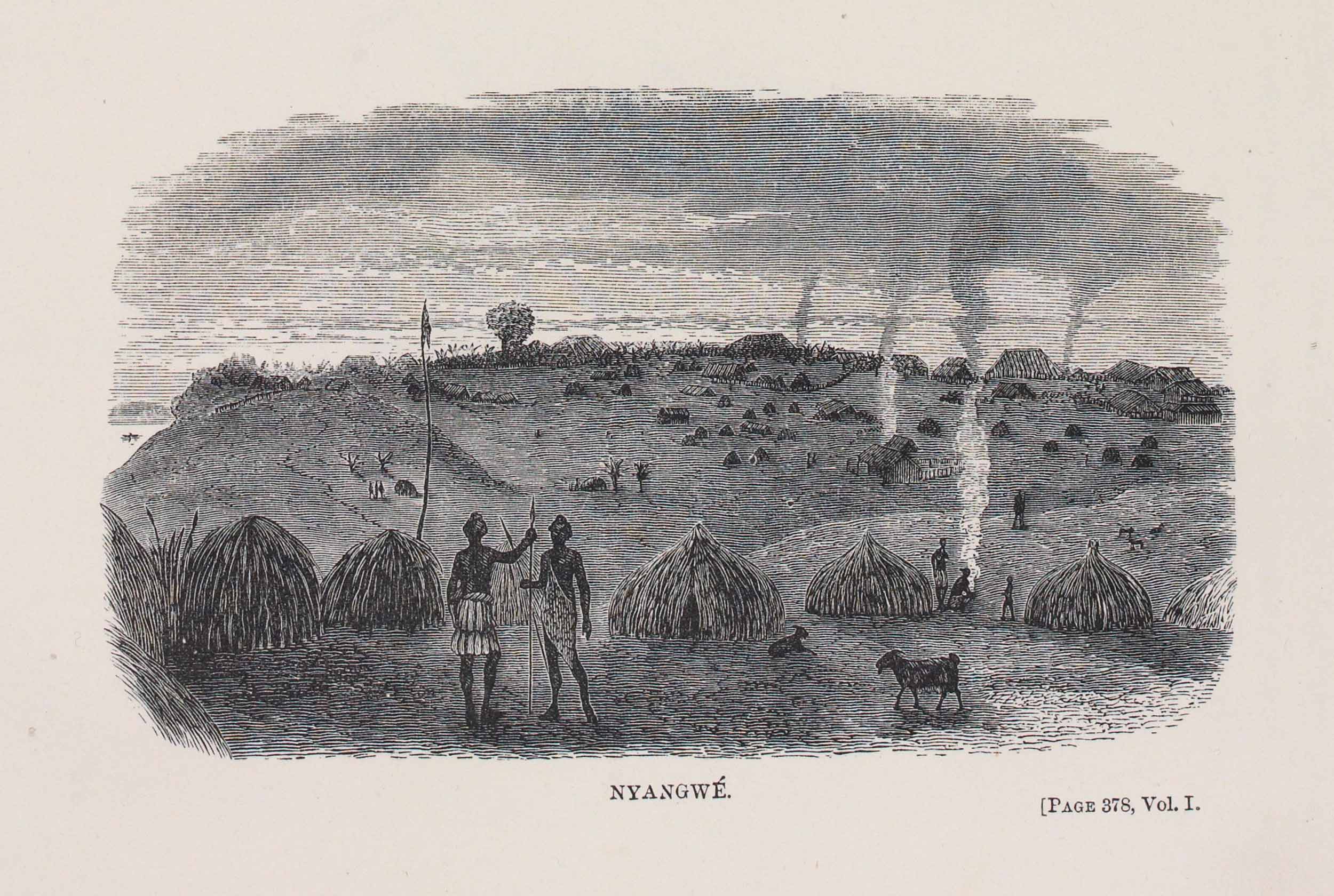

"Nyangwe" from Verney Lovett Cameron's Across Africa (1877,1:opposite 378). Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland

In June, however, while at Nyangwe, Livingstone witnessed a massacre of the local Manyema market perpetrated by slave traders in the region. The circumstances that led to the massacre are complex, and Livingstone’s diaries and journals show considerable confusion about the events that triggered the attack (Wisnicki 2017). It is estimated that between three hundred to four hundred people were killed, with a majority being the women who usually attended the market.

Although Livingstone had considerable exposure both to the slave trade and its attendant conflicts, this experience proved particularly traumatic (Wisnicki 2017). Indeed, his accounts of the massacre, which would later circulate widely in Britain, provided an inspiration to other Victorian abolitionists who would lobby intensively for an anti-slavery treaty between Britain and Zanzibar (Helly 1987:26: Ross 2002:220-21).

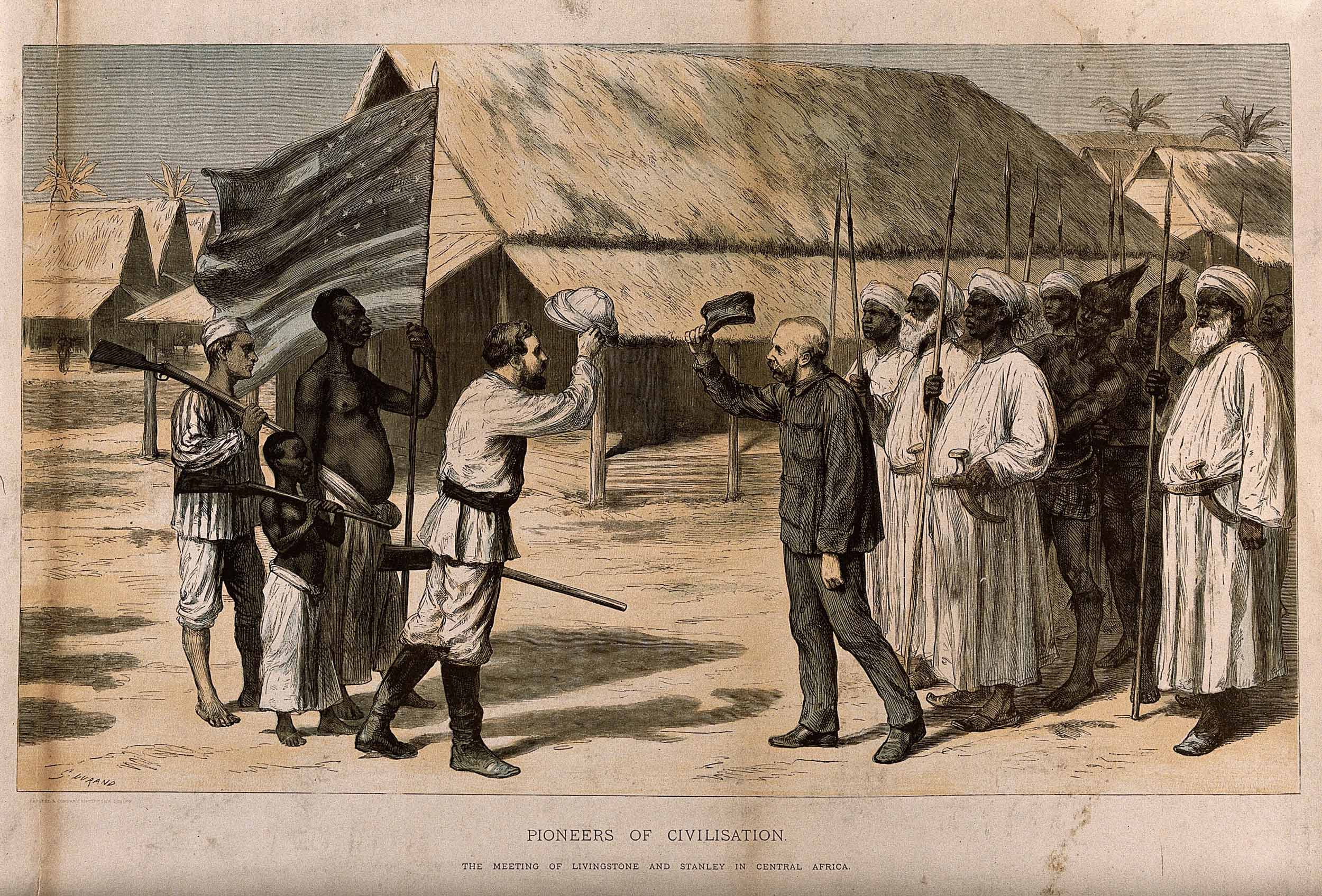

The Nyangwe massacre also directly affected Livingstone’s plans. Horrified by the experience, he now decided to retreat to Ujiji where he planned to recuperate. There, he discovered to his regret that the goods that had been sent to him from the coast by John Kirk had been squandered and that he was consequently short of supplies. The return to Ujiji, however, paved the way for one of the most important meetings of Livingstone’s career. In early November 1871, Henry Morton Stanley entered the town bearing the flag of the United States and supposedly greeted Livingstone with the now famous question, "Dr. Livingstone, I presume?"

"Pioneers of Civilization: The Meeting of Livingstone and Stanley in Central Africa." Copyright Wellcome Library, London. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

Stanley was in pursuit of a “scoop” and his success in tracking down Livingstone for an exclusive interview became an international news story, reported on both sides of the Atlantic (Pettitt 2007:95; Rubery 2009:147). The young New York Herald journalist also brought much needed relief to the destitute explorer. During the months that Stanley and Livingstone subsequently spent together, they explored the northern end of Lake Tanganyika. Later, Stanley’s skillful negotiation of the media and his bestselling book – How I Found Livingstone (1872) – served to consolidate Livingstone’s celebrity and helped to shape the way in which he would be remembered by future generations.

Livingstone’s Death and Burial (1872-73) Top ⤴

Despite Stanley’s attempts to persuade Livingstone to return to Britain, the latter refused to do so. Instead, after being sent fresh supplies and new porters, Livingstone continued on his mission to establish the source of the Nile and journeyed to the south-eastern side of Lake Tanganyika and Lake Bangweulu. However, he became increasingly ill with fever, anal bleeding, and excruciating back pain, and eventually became too weak to walk unsupported. At the end of April 1873 he died in the village of Chitambo (present-day Chipundu, Zambia).

Following Livingstone’s death, the remaining members of his caravan made the decision to transport his remains to Bagamoyo on the east African coast. After disinterring and embalming the body, they set off on a journey lasting five months and covering over a thousand miles. Again, this considerable expedition is a reminder that the intermediaries with whom Livingstone and other explorers journeyed were accomplished travellers in their own right. The skills they possessed were of such value that some of them – including Jacob Chuma, who accompanied Livingstone – were regularly sought out by European explorers to participate in their expeditions (Kennedy 2013:170).

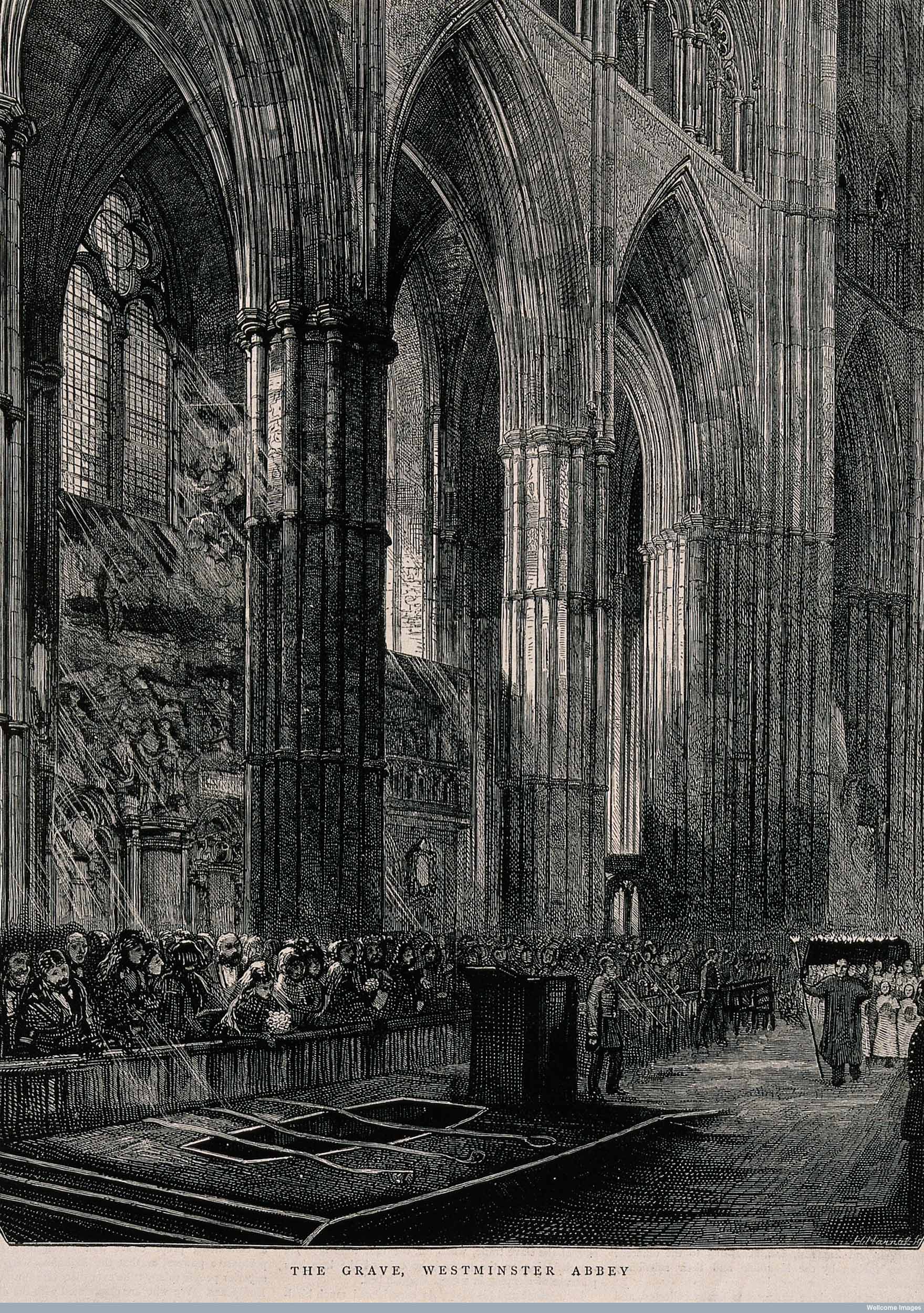

When Livingstone’s body reached the coast, it was shipped to Britain, arriving in Southampton on 15 April before being sent on to London. While he was already famed across Britain, the circumstances of his death and the transcontinental journey of his remains further captured the national imagination: for the Victorians, Livingstone embodied heroic ideals and had died the death of a martyr.

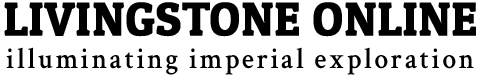

| (Left) The Grave, Westminster Abbey. Copyright Wellcome Library, London. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (Right) Illustrations from Review of Livingstone's Last Journals, Illustrated London News 64 (1874), pp. 381 (Cover), 392, 401, 41. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland |

Under pressure from the public, and from interest groups like the RGS, the government prepared a stately funeral at Westminster Abbey on 18 April (Wolffe 2000:139-40; Lewis 2007; Livingstone 2012). The astonishing expression of grief that the event provoked indicates the extent to which Livingstone took on the status of a sort of “protestant saint” (MacKenzie 1992:124): indeed, his powerful symbolism would allow others, well into the twentieth century, to invoke his name for a range of missionary, political, and imperialist purposes (MacKenzie 1990, 1996; Livingstone 2014)

Acknowledgements Top ⤴

This is an expanded version of a piece entitled “Livingstone’s Expeditions,” originally published in Susannah Rayner, ed., The Life and Afterlife of David Livingstone (London: SOAS University of London, 2014), 45-55. It is extended here with the kind permission of SOAS, University of London.

Works Cited Top ⤴

Astore, William J. 2004. “Dick, Thomas (1774-1857).” Online edition. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Blaikie, William Garden. 1880. The Personal Life of David Livingstone. London: John Murray.

Clendennen, G.W. 1989. “Who Wrote Livingstone’s ‘Narrative’?” The Bibliothek; a Scottish Journal of Bibliography and Allied Topics 16 (1): 30-39.

Dritsas, Lawrence. 2010. Zambesi: David Livingstone and Expeditionary Science in Africa. London: I.B. Tauris.

Driver, Felix, and Lowri Jones. 2009. Hidden Histories of Exploration. London: Royal Holloway, University of London.

Harrison, Debbie. 2012. “A Pioneer Working on the Frontiers of Western and Tropical Medicine.” In David Livingstone: Man, Myth and Legacy, edited by Sarah Worden, 69-81. Edinburgh: National Museums Scotland.

Helly, Dorothy O. 1987. Livingstone’s Legacy: Horace Waller and Victorian Mythmaking. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press.

Holmes, Timothy. 1993. Journey to Livingstone: Exploration of an Imperial Myth. Edinburgh: Canongate.

Jeal, Tim. 2013. Livingstone: Revised and Expanded Edition. New Haven, CT; London: Yale University Press.

Kennedy, Dane. 2013. The Last Blank Spaces: Exploring Africa and Australia. Cambridge, MA; London: Harvard University Press.

Koivunen, Leila. 2001. “Visualizing Africa — Complexities of Illustrating David Livingstone’s Missionary Travels.” Ennen & Nyt 1: 1-12.

Koivunen, Leila. 2009. Visualizing Africa in Nineteenth-Century British Travel Accounts. New York: Routledge.

Lawrence, Chris. 2015a. “Fever in the Tropics.” Second edition. In Livingstone Online: Illuminating Imperial Exploration, directed by Adrian S. Wisnicki, Megan Ward, Anne Martin, and Christopher Lawrence. New version, second edition. College Park, MD: University of Maryland Libraries.

Lawrence, Chris. 2015b. “Livingstone’s Medical Education.” Second edition. In Livingstone Online: Illuminating Imperial Exploration, directed by Adrian S. Wisnicki, Megan Ward, Anne Martin, and Christopher Lawrence. New version, second edition. College Park, MD: University of Maryland Libraries.

Lewis, Joanna. 2007. “Southampton and the Making of an Imperial Myth: David Livingstone’s Remains.” In Southampton: Gateway to the British Empire, edited by Miles Taylor, 31-48. I.B. Tauris.

Livingstone, David. 1856. “Manuscript of Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa (1856-57).” National Library of Scotland, Scotland. MS. 42428-9. John Murray Archive.

Livingstone, David. 1857a. “Letter to John Murray, 30 May 1857.” National Library of Scotland, Scotland. MS. 42425. John Murray Archive.

Livingstone, David. 1857b. Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa. London: John Murray.

Livingstone, David, and Charles Livingstone. 1865. Narrative of an Expedition to the Zambesi and Its Tributaries. London: John Murray.

Livingstone, Justin D. 2011. “‘The Meaning and Making of Missionary Travels: The Sedentary and Itinerant Discourses of a Victorian Bestseller.’” Studies in Travel Writing 15 (3): 267-92.

Livingstone, Justin D. 2012. “A ‘Body’ of Evidence: The Posthumous Presentation of David Livingstone.” Victorian Literature and Culture 40 (1): 1-24.

Livingstone, Justin D. 2014. Livingstone’s Lives. A Metabiography of Victorian Icon. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

MacKenzie, John M. 1990. “David Livingstone: The Construction of the Myth.” In Sermons and Battle Hymns: Protestant Popular Culture in Modern Scotland, edited by Graham Walker and Tom Gallagher, 24-42. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

MacKenzie, John M. 1992. “Heroic Myths of Empire.” In Popular Imperialism and the Military, edited by John M. MacKenzie, 109-37. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

MacKenzie, John M. 1996. “David Livingstone and the Worldly After-Life: Imperialism and Nationalism in Africa.” In David Livingstone and the Victorian Encounter with Africa, edited by John M. MacKenzie, 203-16. London: National Portrait Gallery.

MacKenzie, John M. 2013. “David Livingstone – Prophet or Patron Saint of Imperialism in Africa: Myths and Misconceptions.” Scottish Geographical Journal 129 (3-4): 277-91.

Martelli, George. 1970. Livingstone’s River: A History of the Zambesi Expedition, 1858-1864. London: Chatto & Windus.

Mullen, Stephen. 2012. “One of Scotia’s ‘Sons of Toil’: David Livingstone and the Blantyre Mill.” In David Livingstone: Man, Myth and Legacy, edited by Sarah Worden, 15-31. Edinburgh: National Museums Scotland.

Murray, John. 1857a. “Letter to David Livingstone, 5 Jan. 1857.” National Library of Scotland, Scotland. MS. 41912. John Murray’s Letter Book, Mar. 1846 - Apr. 1858. John Murray Archive.

Murray, John. 1857b. “Letter to David Livingstone, 19 Jan. 1857.” National Library of Scotland, Scotland. MS. 41912. John Murray’s Letter Book, Mar. 1846 - Apr. 1858. John Murray Archive.

Parsons, Neil. 1998. Khama, Emperor Joe, and the Great White Queen: Victorian Britain through African Eyes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Pettitt, Clare. 2007. Dr. Livingstone, I Presume?: Missionaries, Journalists, Explorers, and Empire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Roberts, A.D. 2004. “Livingstone, David (1813-1873).” Online edition. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rockel, Stephen. 2014. “Decentering Exploration in East Africa.” In Reinterpreting Exploration: The West in the World, edited by Dane Kennedy, 172-94. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ross, Andrew. 2002. David Livingstone: Mission and Empire. London: Hambledon Press.

Ross, Andrew. 2005. “David Livingstone.” Études Écossaises 10: 89-102.

Rubery, Matthew. 2009. The Novelty of Newspapers: Victorian Fiction after the Invention of the News. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schapera, Isaac, ed. 1961. Livingstone’s Missionary Correspondence, 1841-1856. London: Chatto & Windus.

Stanley, Brian. 2014. “The Missionary and the Rainmaker: David Livingstone, the Bakwena, and the Nature of Medicine.” Social Sciences and Missions 27 (2-3): 145-62.

Stanley, Henry M. 1872. How I Found Livingstone (etc.). London: Sampson Low, Marston, Low, and Searle. 1872.

Wingfield, Chris. 2012. “Remembering David Livingstone 1973-1935: From Celebrity to Saintliness.” In David Livingstone: Man, Myth and Legacy, edited by Sarah Worden, 115-29. Edinburgh: National Museums Scotland.

Wisnicki, Adrian S. 2009. “Interstitial Cartographer: David Livingstone and T He Invention of South Central Africa.” Victorian Literature and Culture 37 (1): 255-71.

Wisnicki, Adrian S. 2017. “Livingstone in 1871.” Updated version. In Livingstone’s 1871 Field Diary: A Multispectral Critical Edition, directed by Adrian S. Wisnicki. Updated version. Livingstone Online, directed by Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward. New version, second edition. College Park, MD: University of Maryland Libraries.

Wolffe, John. 2000. Great Deaths: Grieving, Religion, and Nationhood in Victorian and Edwardian Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press.