Livingstone's Medical Education

Cite page (MLA): Lawrence, Christopher. "Livingstone's Medical Education." Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, eds. Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. University of Maryland Libraries, 2015. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/ce8c001e-9bd3-4995-8b37-37477601e8f8.

This essay provides a detailed description of Livingstone’s medical education as well as an overview of how his education affected his recording strategies in Africa.

Introduction Top ⤴

As is well known, Livingstone was born into a poor, deeply religious family at Blantyre, near Glasgow, Scotland. After rudimentary schooling he worked in the town's cotton mill. What set him apart from an early age was his voracious appetite for reading and his interest in natural history, which was in many ways the premier science of nineteenth-century Britain. At the age of twenty-one, he simultaneously determined to become a missionary and decided that a medical training would be invaluable in carrying out this plan, an unusual combination so early in the century.

Medical Education during the Nineteenth Century Top ⤴

During the early nineteenth century, medical education was undergoing turbulent changes. University education was not then, as it is now, the most common route to qualification. University education usually resulted in an MD but practitioners of all sorts were called doctor by courtesy even though they did not have a medical degree. Livingstone was one such practitioner. Apprenticeship to an apothecary or a surgeon was one possible route to qualification in those years and was chosen by a large number of young men (medical qualifications could then be obtained only by men).

Most youths entering the profession in Britain were going to join the swelling ranks of general practitioners. These doctors were distinguished from the wealthier surgeons and physicians with large private practices and hospital posts who were beginning to call themselves consultants. Most general practitioners or military and naval doctors were educated by attending lectures at private medical schools or schools attached to the great hospitals and dispensaries, followed by bedside instruction in hospitals.

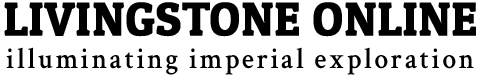

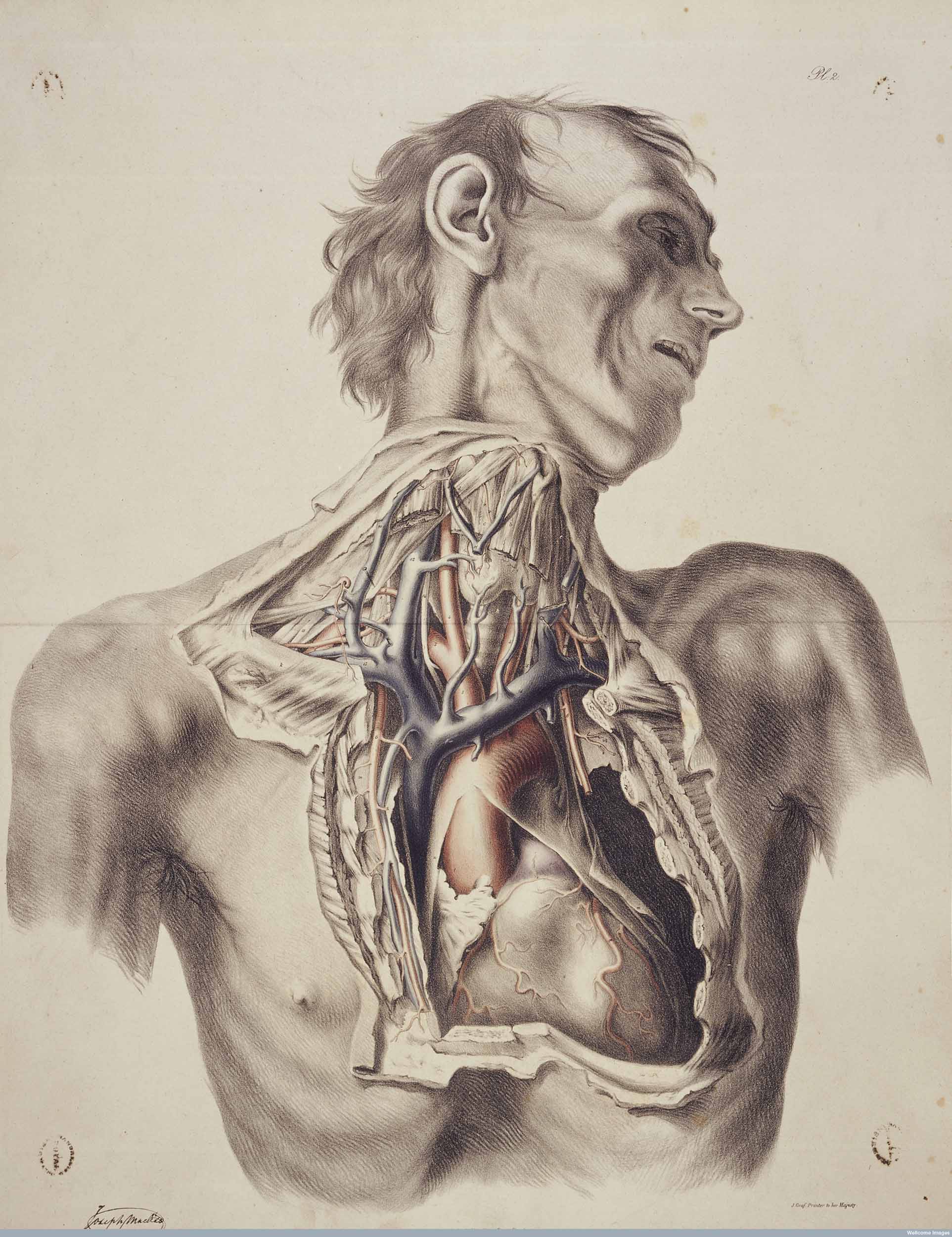

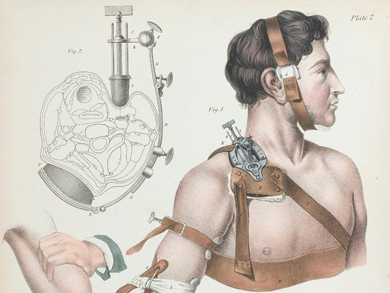

| (Left) The large arteries of thorax and neck. Copyright Wellcome Library, London. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (Right) Surgical instruments used to treat venereal diseases. Copyright Wellcome Library, London. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International |

Classes were also given by teachers associated with some of the ancient medical corporations. These were the Royal Colleges of Physicians and of Surgeons in London and Edinburgh, the Royal College of Surgeons of Ireland and the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow.

The surgical corporations, besides offering medical classes, were also examining and licensing bodies. A student properly equipped with certificates of attendance at the requisite number of recognised courses could present himself for examination at one these bodies and, if successful, could receive a licence to practise. The requirements of the corporations varied slightly but a student would normally attend the following classes:

|

The student would attend a hospital and follow two or more courses of clinical (bedside) instruction in surgery and medicine. Experience in midwifery and attendance at surgical operations were also required.

Livingstone’s Medical Education in Scotland Top ⤴

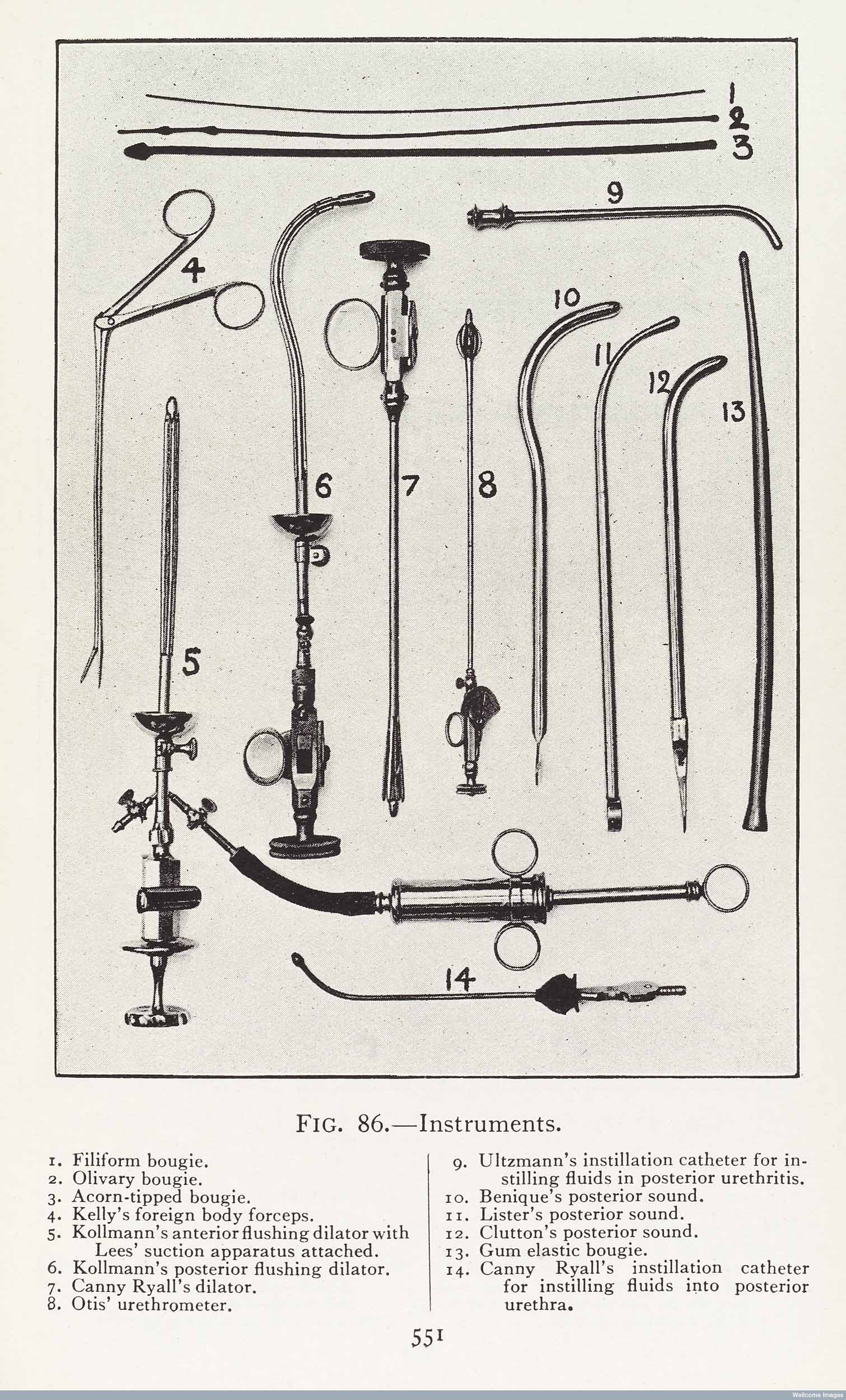

This was the educational route that Livingstone chose. He began studying medicine at Anderson's University Glasgow (also known as Andersonian University Glasgow), in 1836. Anderson's Institution was established in 1796 under the will of John Anderson. In 1828 its name was changed to Anderson's University. It was forced to change its name to Anderson's College in 1877 because it did not have a Royal Warrant. Its medical school had been established in 1800. It was a basic medical college and the student would need to go elsewhere to gain bedside experience and a licence to practise.

For a child from his background it is no exaggeration to say that Livingstone's attendance at Anderson's University was an extraordinary achievement. Every Monday in term time he walked the eight miles to Glasgow where he had lodgings. During vacations he worked at the mill. At Anderson's, Livingstone took the anatomy course which ran from 1 November 1836 to 25 April 1837. This was a series of lectures, possibly enlivened by the display of wax models and injected preparations.

In the same academic year he also took the course in practical anatomy. In this course he would have observed dissection and almost certainly dissected human corpses for himself. Livingstone retook the course of lectures in anatomy in 1838-1839. This was not because he had failed – there were no examinations – since his authenticated certificate for 1836-1837 survives. Ambitious students often took courses twice in order to improve their knowledge.

All the anatomy classes were given by Robert Hunter, an MD, who, in 1840, was on the local committee of the Phrenological Association. Nowhere does Livingstone give any indication of the slightest interest in phrenology, a pursuit at this time often accused of irreligious tendencies. Also in 1836-1837, Livingstone took the course in chemistry given by Thomas Graham.

Livingstone's second year was quite energetic. Besides hearing the anatomy course for the second time, he attended lectures on surgery given by James Adair Lawrie MD who, in 1850, succeeded to the chair of surgery at the Glasgow School of Medicine. Livingstone would learn practical surgery in London. He took two courses in chemistry given by William Graham, one simply called "Chemistry" (a lecture course) and practical chemistry.

He also attended Andrew Buchanan's lectures on materia medica. Andrew Buchanan, is said by Livingstone's biographer William Blaikie to have been Professor of the Institutes of Medicine (now called physiology), and Livingstone probably attended a course of that name but no certificate has been found.

During his two years at Anderson's and, subsequently, his time in London, Livingstone became well acquainted with a number of important figures in science and medicine whose patronage surely helped him in later life. According to Blaikie he enjoyed Graham's lectures, and from James Young, Graham's assistant, Livingstone gained "a knowledge of tools," by which he meant practical experience with scientific instruments and equipment. Young, who later made a fortune out of "Paraffin" and was one of Livingstone's trustees, assisted Livingstone financially after 1857. He was "attracted" too by the teaching of Andrew Buchanan with whom he remained a "life-long and much-attached friend." One of Livingstone's classmates was Lyon Playfair, later Professor of Chemistry at Edinburgh and eventually Baron Playfair. He also met the brothers James Thomson and William Thomson, both of whom were to have outstanding scientific careers.

Garden of John Penn, St James's Park: A charity fair for Charing Cross Hospital, 1830, by G. Scharf. Copyright Wellcome Library, London. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

Livingstone’s Medical Education in England Top ⤴

At the same time as Livingstone studied the basic medical subjects he took classes in Greek (he already knew Latin) and attended theology lectures. After two years at Anderson's he was accepted on probation by the London Missionary Society and he was sent to Chipping Ongar in Essex where his medical studies were temporarily suspended for tuition in Greek, Latin, Hebrew and theology.

In January 1840 he moved to a boarding house for young missionaries in Aldersgate, London. He then attended medical classes and learned clinical skills at the British and Foreign Medical School, the Aldersgate Street Dispensary, Charing Cross Hospital and Moorfields Hospital (an ophthalmic hospital). He also attended the lectures of the comparative anatomist Richard Owen at the Hunterian Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. Livingstone wrote Owen at least eight letters.

Two of these letters (Livingstone 1841; Livingstone 1865) are available on Livingstone Online. The letter of 1841 is especially interesting since it concerns the collection of scientific specimens during his travels. At Charing Cross Hospital Livingstone was taught medicine by James Risdon Bennett to whom Livingstone wrote at least four letters in the 1840s. Bennett was a distinguished London physician. He was a Fellow of the Royal Society and became President of the Royal College of Physicians of England in 1876 and was knighted in 1881. Bennett put down his recollections of Livingstone for William Blaikie, one of Livingstone's first biographers.

The only evidence of Livingstone's medical education in this period is a letter from Risdon Bennett testifying that David attended Bennett's lectures on the theory and practice of medicine, 1839-1840. In London Livingstone also met George Wilson through Thomas Graham, who by now had moved to become Professor of Medicine at University College. Wilson became Professor of Technology at the University of Edinburgh and first Director of the Edinburgh Museum of Science and Art. In November 1840, after examination, Livingstone became a Licentiate of the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow.

![Oath to Faculty of Medicine and Surgery, [1837?], by David Livingstone. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant), and University of Glasgow Photographic Unit. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). Oath to Faculty of Medicine and Surgery, [1837?], by David Livingstone. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant), and University of Glasgow Photographic Unit. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/life-and-times/livingstones-medical-education/liv_000043_0001-article.jpg) Oath to Faculty of Medicine and Surgery, [1837?], by David Livingstone. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant), and University of Glasgow Photographic Unit. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported |

On this occasion Livingstone swore an oath which is very loosely based on the Hippocratic Oath, but much is omitted from the ancient document and other things added (for example, Livingstone swears by "God" not "Apollo"). Livingstone's version of this oath, in his own hand, is almost an exact transcription of the words which were printed in a booklet, The Royal Charter and Laws of the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow, June 5, 1821 (Glasgow, R. Chapman, 1821). On 8 December 1840, a qualified practitioner, Livingstone set sail for Cape Town.

Livingstone’s Medical Records from Africa Top ⤴

Livingstone’s medical education influenced the records he kept throughout his travels in Africa. Indeed, the majority of Livingstone's letters contain some mention of science or medicine, including:

|

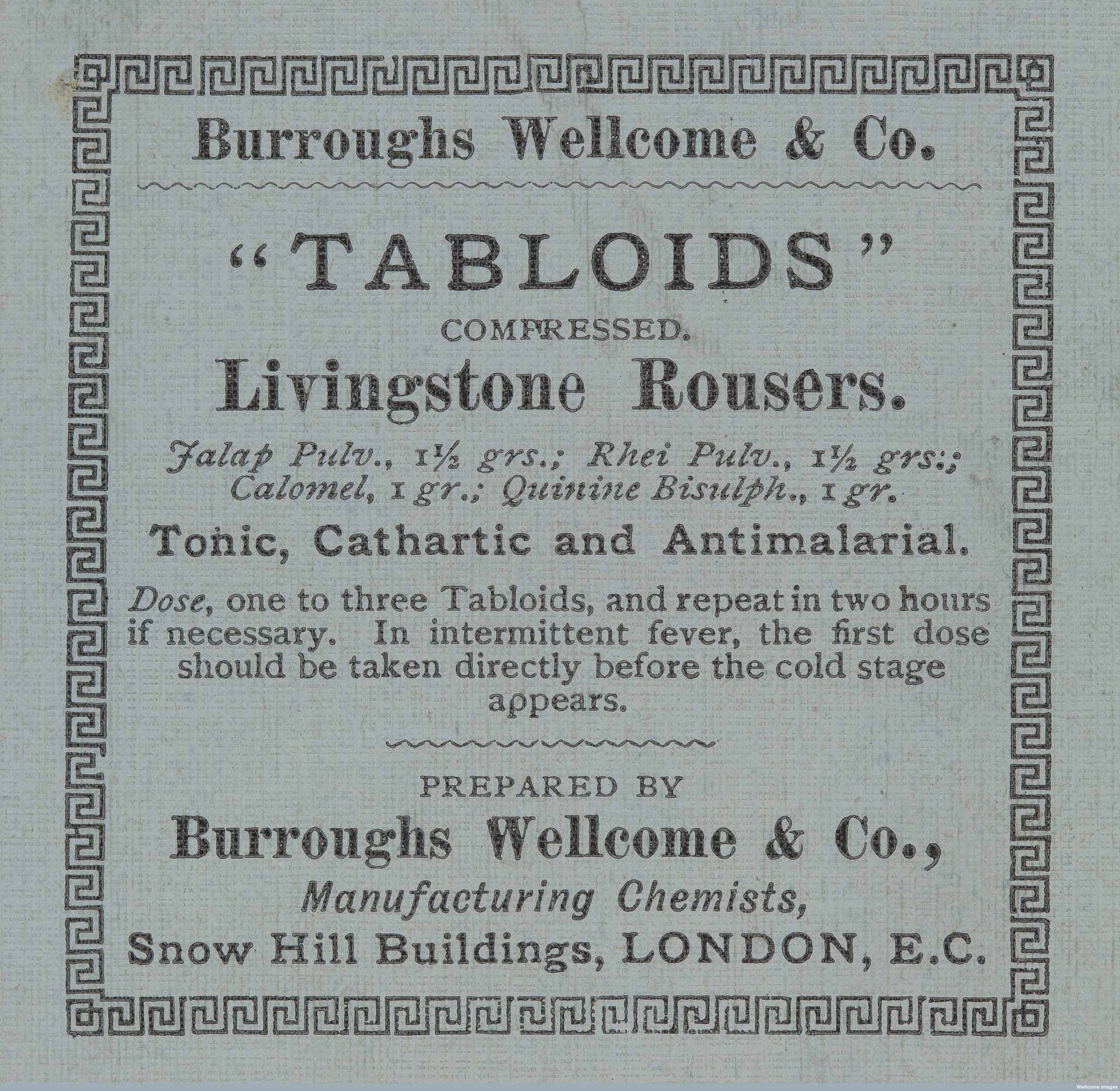

Pharmaceutical advert for 'Tabloids', compressed Livingstone Rousers. Copyright Wellcome Library, London. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International |

Livingstone’s medical education encouraged prospective doctors to think about health and illness on the widest of canvases. This had been an integral part of western medicine since antiquity. One of the most revered works of the writings attributed to Hippocrates and included in the so-called Hippocratic Corpus was “Airs, waters and places.” In modern language this was a study of the geography, geology, meteorology and anthropology of the Mediterranean region. It was a compilation of observations of the peoples of the area, the diseases to which they were susceptible and the climates and environments likely to be conducive to health.

Livingstone's letters are steeped in this tradition. He repeatedly recorded his medical observations of the tribes of Africa, whether a region was salubrious or not, and so on. Retrospectively these observations can be designated geological, meteorological, natural historical and so forth. In fact, for Livingstone, they were also medical. Taken together, we can see these observations also imagining the possibilities for colonization. Livingstone was interested every aspect of an area in order to discover whether it was suitable for European settlement or likely to produce insurmountable poor consequences for health. As a result, Livingstone’s medical education influenced his life as a missionary, explorer, and writer.

Works Cited Top ⤴

Chapman, R. 1821. The Royal Charter and Laws of the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow, June 5, 1821. Glasgow.

Livingstone, David. 1841. “Letter to Richard Owen.” MS. 7329 01. Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine. Library.

Livingstone, David. 1865. “Letter to Richard Owen.” MS. 7329 55. Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine. Library.