Textual Principles and Encoding Practices

Cite (MLA): Livingstone, Justin D. "Textual Principles and Encoding Practices." Adrian S. Wisnicki, ed. In Livingstone's Missionary Travels Manuscript. Justin D. Livingstone and Adrian S. Wisnicki, dirs. Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. 2019. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/29018935-eb5f-4ce9-ad16-c93bf898ae74.

This essay presents an editorial statement for our critical edition of Livingstone's Missionary Travels manuscript. The essay outlines the textual principles and encoding practices that the project team has applied to document key characteristics of the manuscript, and then offers a detailed enumeration of the modes of display used to represent specific features onscreen.

1. Textual Principles and Encoding Practices: An Overview Top ⤴

Standing at over 1100 pages and full of the complexities and messiness of a working draft, the Missionary Travels manuscript is demanding both for readers and for those who take on the task of editing. For digital editors, the challenge lies not only in identifying and apprehending diverse textual features, but in representing them to users coherently. Digital editing, as one critic writes, is “a ruthlessly demanding practical craft” and one that requires careful attention to the needs of “reader-viewers” (Eaves 2015:1).

The present edition follows diplomatic textual principles and so aspires towards as much fidelity to the original document as possible, recording errors and accidentals rather than making silent corrections. The development of the digital humanities has undoubtedly led to renewed enthusiasm for such approaches. In transcribing the pages of the Missionary Travels manuscript as they appear, this edition coheres with the “documentary” practices of many recent digital projects, where the objective is to record and reproduce the features and “peculiarities of the document itself” (Pierazzo 2014). Examples of such projects include Jane Austen’s Fiction Manuscripts, The Shelley-Godwin Archive, and The Occom Circle as well as longer-running initiatives such as The Walt Whitman Archive and The William Blake Archive.

![Image of a page from the Missionary Travels manuscript, as displayed in the Livingstone Online manuscript viewer (Livingstone 1857bb:[110]). Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/). Image of a page from the Missionary Travels manuscript, as displayed in the Livingstone Online manuscript viewer (Livingstone 1857bb:[110]). Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/missionary-travels-manuscript/textual-principles-and-encoding-practices/MS-viewer-liv_000099_0110-article.png)

Image of a page from the Missionary Travels manuscript, as displayed in the Livingstone Online manuscript viewer (Livingstone 1857bb:[110]). Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. The manuscript page presented here has been heavily marked up in red ink and pencil by the literary editors employed by Livingstone's publisher, John Murray. The individual using red ink is probably the literary reviser, John Milton; the identity of the individual using pencil is unknown.

The present edition similarly devotes considerable attention to the unique features of the Missionary Travels manuscript in encoding and in onscreen representation. This method follows the practices outlined in Livingstone Online’s detailed TEI encoding guidelines, ensuring that the manuscript is thoroughly described and that the markup documents both the appearance and layout of the physical page. For instance, the edition’s encoding delineates: new lines; new paragraphs; new pages; running headers; additional spaces between words and lines; gaps in the manuscript (as a result of illegibility or damage); and textual formatting such as underlining, superscript, and subscript.

Furthermore, the encoding records textual additions and their location in relation to the body of the text (inline, above, below, marginleft and marginright) as well as each instance of deletion. The details of redaction are captured with as much precision as possible; in cases of overwriting the encoding points to the sequence of correction, distinguishing between textual layers by recording both the undertext (i.e., lower layer of text) and overtext (upper layer). The editorial team has likewise documented other features, such as the various hands involved in textual production, changes in the colour of writing, and the range of proof correction marks that appear in the manuscript.

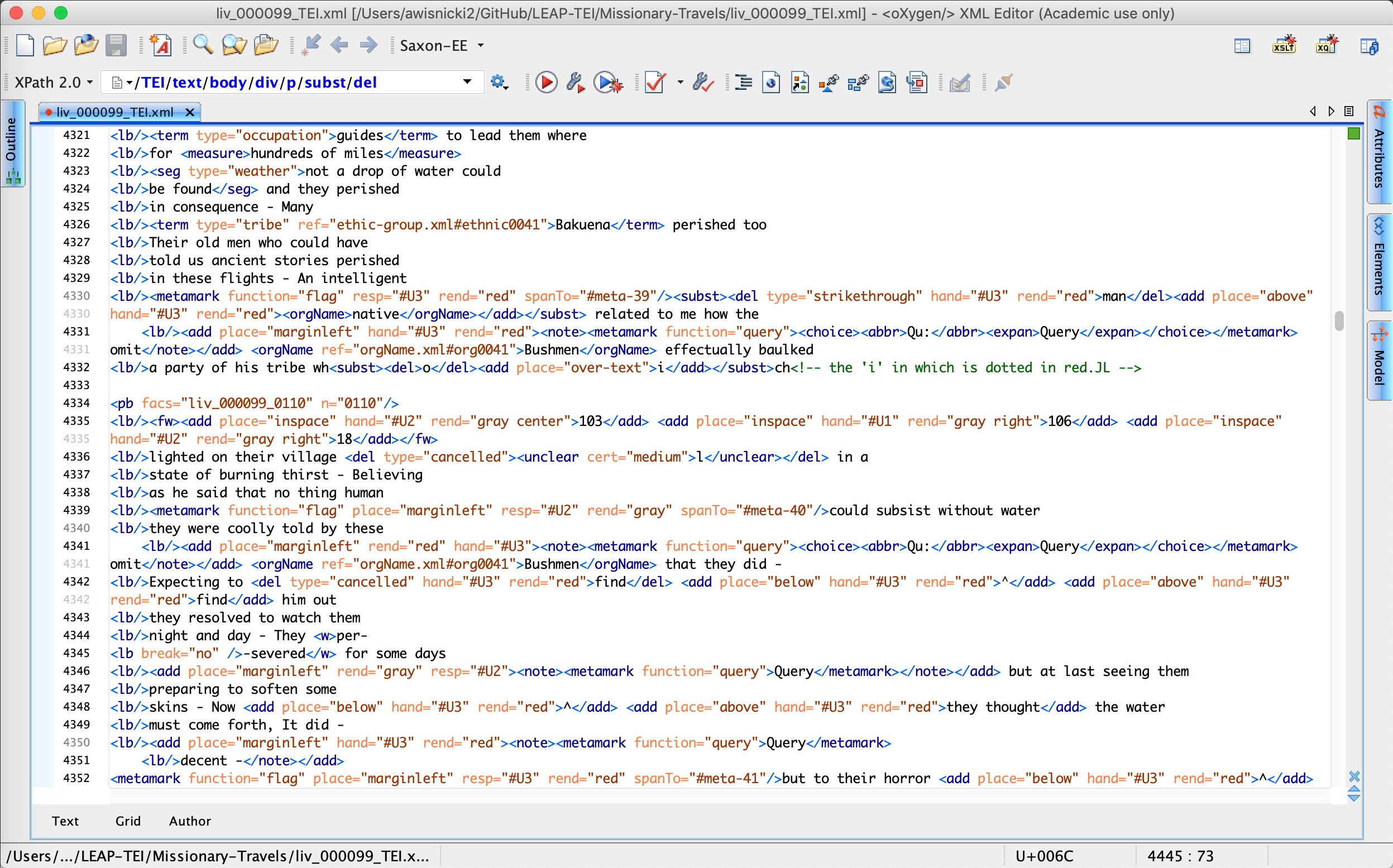

Transcription of a page from the Missionary Travels manuscript, encoded in XML TEI P5. Copyright Livingstone Online. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. This portion of the transcription partly corresponds to the manuscript page shown in the image of the Livingstone Online manuscript viewer above (see previous image), and demonstrates the complexity and scale of the editorial markup and encoding practices used in the present edition in order to prepare the Missionary Travels manuscript for online display.

The onscreen representations enabled by these encoding practices bring considerable advantages to an edition occupied with the processes of composing and revising a work of travel. The transcriptions, for instance, show where an editor has scored out one of Livingstone’s words in red ink or where Livingstone has scribbled over a reader’s comment written in pencil. The encoding thus facilitates a dynamic visual display of a nuanced, multi-stage, multi-hand material document without recourse to the “complex typographic schemes” that would have been necessary to convey such details in print (Eaves, Loy, Sidhu, and Whitebell 2015:5).

That said, the present edition has still required a system, first, to represent manuscript features that are not easily displayed on screen and, second, to signal any editorial interventions made by the project team. The following sections of this essay explore the modes of visual display employed in the edition in greater detail.

2. Livingstone Online’s Display Practices and the Missionary Travels Manuscript Top ⤴

In its onscreen rendering of the Missionary Travels manuscript, the present edition draws on many of Livingstone Online’s general display practices to produce readable and critically informed transcriptions. These modes of display, used in both this edition and elsewhere on the site, serve to represent key characteristics of Livingstone’s manuscripts and to integrate editorial commentary and corrections into transcriptions in an unobtrusive way.

This section provides a brief overview of major manuscript features, a description of how the edition represents the given features onscreen, the text of the corresponding tooltips (i.e., text box that appears onscreen when a user mouses over a feature), and any additional relevant notes.

▲ 2.1. Additions from Another Part of the Page

Overview: The MS contains numerous additions written on various parts of the page (but normally in the left-hand margin), which are intended for insertion in the body of text.

Onscreen display: Enclosed within [ and ] and integrated into the narrative where the passage is intended for insertion.

Tooltip: Notes the location on the page in which the addition appears, as in the following example: “addition, place: marginleft.”

Note: This representational format (i.e., integrating textual additions into the body of text) does not follow the physical appearance of the manuscript, but does ensure legibility and a fluid reading experience for users. It should be noted that textual comments and queries by author and editor are represented with a different method (see Textual Comments, below).

▲ 2.2. Text Written over Other Text

Overview: The MS contains numerous instances of overwriting where the author or an editor has written over an existing layer of text.

Onscreen display: Represented by placing the original layer of text (i.e., the undertext) and the added text (i.e., overtext) side by side. The undertext is displayed in gray and cancelled with a single gray line, and the overtext is enclosed within { and } .

Tooltip: “addition, place: over-text.”

▲ 2.3. Textual Errors

Overview: The MS contains typographical errors which have been corrected by the project team.

Onscreen display: Displayed in uncorrected form with a red dotted underline.

Tooltip: “The editors suggest a correction as follows: [suggested correction].”

▲ 2.4. Uncertain Transcriptions

Overview: The MS contains some words that are unclear and so cannot be transcribed with certainty.

Onscreen display: Displayed in gray with a gray dotted underline.

Tooltip: Notes the relative certainty of the transcribed word as follows: “word(s) unclear; certainty of transcription: [low/medium/high].”

▲ 2.5. Critical Notes

Overview: The MS contains references to people, places, organisations, and various other terms of significance for which the edition provides critical notes of explanation.

Onscreen display: Indicated by a blue dotted underline.

Tooltip: Contains the corresponding critical note.

3. Customized Display Practices: Text in Other Hands Top ⤴

The Missionary Travels manuscript also has unique features that require customized onscreen modes of display. These additional practices, which complement Livingstone Online’s usual methods (or, in some cases, depart from them), chiefly concern the various hands that appear in the document as well as the wide ranging editorial markup used by both Livingstone and John Murray’s literary agents. Together, the onscreen modes of display developed for the Missionary Travels edition ensure that such manuscript contributions are captured visually in transcription and provided with editorial notes of interpretation.

![Image of two pages from the Missionary Travels manuscript (Livingstone 1857dd:[181]-[182]). Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/). Image of two pages from the Missionary Travels manuscript (Livingstone 1857dd:[181]-[182]). Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/missionary-travels-manuscript/textual-principles-and-encoding-practices/liv_000101_0181-0182-article-1200.jpg)

Image of two pages from the Missionary Travels manuscript (Livingstone 1857dd:[181]-[182]). Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. The page on the right is in the hand of David Livingstone's brother, Charles Livingstone. The page on the left shows supplementary text (intended for insertion in the page on the right) in both David and Charles Livingstone's hands.

The multiple hands involved in the Missionary Travels manuscript are among its most significant features. Published travel narratives usually conceal their mediated nature, but literary manuscripts – as in the present case – can unmask the critical interventions to which travel books were subject in the course of composition and publication. The Missionary Travels manuscript provides evidence of a range of contributors including:

- David Livingstone himself;

- David Livingstone’s brother Charles Livingstone;

- an amanuensis (possibly Livingstone’s neighbour, Wilbraham Taylor);

- the publisher’s readers (including the literary reviser, John Milton);

- the author of an inscription (possibly Rev. Dr. P. H. Keith); and

- a later librarian.

(For more information on the multiple hands in Missionary Travels, see State of the Manuscript: An Overview.)

This section provides a brief overview of manuscript features involving other hands (additions, deletions, and overwriting) and, like the previous section, offers a description of how the edition represents the given features onscreen, the text of the corresponding tooltips (i.e., text box that appears onscreen when a user mouses over a feature), and any additional relevant notes.

▲ 3.1. Text Added by Another Hand

Overview: The MS contains a considerable body of material written by other hands. This material appears in a range of colours including black, brown, red, and gray.

Onscreen display: Displayed in the colour in which the text appears in the original MS.

Tooltip: Notes the hand, location, and colour of the addition (where relevant), as in the following examples:

- “addition, hand: #U3; place: inline; rend: red.”

- “addition, hand: #CL; place: marginleft.”

- “addition, hand: #DL; place: above.”

As in the examples above, where the majority hand is David Livingstone’s, tooltips indicate those additions that have been made by other contributors. Where the default hand belongs to Charles Livingstone or David Livingstone’s amanuensis, tooltips signal additions by David Livingstone himself and other contributors.

Note: The colour of Charles Livingstone’s handwriting is sometimes indistinguishable from David Livingstone’s, so the former’s hand is also displayed in italics.

▲ 3.2. Text Deleted by Another Hand

Overview: The MS contains numerous deletions by other hands, which appear in a range of colours including black, brown, red, and gray.

Onscreen display: Displayed in the color in which the deletion appears in the original MS.

Tooltip: Notes the hand, color, and type of deletion (strikethrough or cancelled) as in the following examples:

- “deletion, hand: #U3; rend: red; type: strikethrough.”

- “deletion, hand: #U2; rend: gray; type: cancelled.”

▲ 3.3. Text Retraced by Another Hand

Overview: The MS contains a range of retraced material. Words are retraced when they are overwritten with the same text in a different hand. This overwriting generally seeks to confirm a suggested addition.

Onscreen display: Displayed in the colour of the top layer of text (i.e., the overtext) and signalled with a gray dotted underline.

Tooltip: Provides notes of explanation, as in the following examples:

- “Text retraced in gray by an editor.”

- “Text retraced in red by an editor.”

- “Text retraced by David Livingstone.”

- “Text retraced by Charles Livingstone.”

4. Customized Display Practices: Authorial and Editorial Markup Top ⤴

Another significant characteristic of the Missionary Travels manuscript is the considerable range of authorial and editorial markup that it contains as a working draft. For instance, comments and queries about particular passages appear in the manuscript’s margins, sometimes written by Livingstone but more often by John Murray’s literary editors. Additionally, there are numerous proof correction marks, arrows and lines, and other editorial annotations that serve to correct and alter how the text should be read.

![Image of a page segment from the Missionary Travels manuscript (Livingstone 1857bb:[356]), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/). Image of a page segment from the Missionary Travels manuscript (Livingstone 1857bb:[356]), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/missionary-travels-manuscript/textual-principles-and-encoding-practices/liv_000099_0356-article-crop.jpg)

Images of two page segments from the Missionary Travels manuscript (Livingstone 1857bb:[47], [356]), detail in both cases. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. The top segment shows a passage of text cancelled both by one of Livingstone's editors (whose identity is unknown) in pencil and by Livingstone in black ink; the marginal annotation in the same segment – written first by the editor and then retraced by Livingstone – is the proof correction mark for "delete." The bottom segment shows a marginal comment by another editor (probably the literary reviser, John Milton) in red ink instructing that text from the previous page be moved here: "Insert paragraph from last page A.”

The digital markup of the Missionary Travels holograph distinguishes it from most other documents on Livingstone Online. While the site’s project team has encoded all textual marks appearing in other manuscripts indiscriminately with the <metamark/> tag, the complex deployment of proof correction symbols and editorial annotation in Missionary Travels requires more nuanced encoding. This edition thus breaks with Livingstone Online’s general practice by introducing a number of functions for the <metamark/> tag. These functions specify the particular purposes that each mark serves in the manuscript: e.g., <metamark function=“insertion”>. (For further information on unique encoding practices for the Missionary Travels manuscript, see the relevant section of the Livingstone Online TEI guidelines.)

This section provides a brief overview of manuscript features involving authorial and editorial markup and, like the previous two sections, offers a description of how the edition represents the given features onscreen, the text of the corresponding tooltip (i.e., text box that appears onscreen when a user mouses over a feature), and any additional relevant notes.

▲ 4.1. Textual Comments

Overview: The MS contains numerous comments and queries by the author and editors written on various parts of the page (but normally in the left-hand margin).

Onscreen display: Displayed in the location in which they appear in the original MS.

Tooltip: Notes the hand, location, and colour of the comment (where relevant), as in the following examples:

- “addition, hand: #U3; place: inline; rend: red.”

- “addition, hand: #CL; place: marginleft.”

- “addition, hand: #DL; place: above.”

Note: This marginalia provides commentary on the text, so is represented differently from additions to content intended for integration into the body of text (see Additions from Another Part of the Page, above).

▲ 4.2. Proof Correction Marks (Including Symbols and Annotations)

4.2.1. Proof Correction Symbol for Close up Space: ︹

Overview: This symbol is used in the MS to indicate that an unnecessary space between words should be reduced.

Onscreen display: Displayed in the location in which it appears in the original MS.

Tooltip: “Editorial symbol used to indicate that the space between words should be reduced.”

4.2.2. Proof Correction Symbol and Annotations for Delete: ₰ - “dele” - “d”

Overview: This symbol and the variant annotations are used in the MS to mark a passage of text for removal.

Onscreen display: Displayed in the location in which they appear in the original MS.

Tooltip:

- For ₰: “Editorial symbol used to mark a deletion.”

- For “dele” or “d”: “Editorial annotation instructing that a portion of text should be deleted.”

4.2.3 Proof Correction Symbol and Annotation for Leave Unchanged: dashed underline - “stet”

Overview: This symbol and the variant annotation are used in the MS to signal that a deleted passage of text should be retained.

Onscreen display: Displayed in the location in which they appear in the original MS.

Tooltip:

- For dashed underline: “Editorial symbol used to indicate that a deleted word or phrase should be retained.”

- For “stet”: “Editorial annotation instructing that a deleted portion of text should be retained.”

4.2.4. Proof Correction Symbols and Annotation for New Paragraph: / - # - “Par.”

Overview: These symbols and the variant annotation are used in the MS in the absence of a paragraph break to indicate where a new paragraph should begin.

Onscreen display: Displayed in the location in which they appear in the original MS.

Tooltip: “Editorial instruction to begin a new paragraph.”

Note: / is used for several other purposes in the MS, including signaling an insertion or substitution, and marking a reader’s place in the text (see Proof Correction Symbol for Substitution and Editorial Symbol Marking a Place in the Text, below). The function the symbol serves in its particular context is explained in the accompanying tooltip.

4.2.5. Proof Correction Symbol for No New Paragraph: ʅ

Overview: This symbol is used in the MS to indicate that a paragraph break should be removed.

Onscreen display: Displayed in the location in which it appears in the original MS.

Tooltip: “Editorial symbol used to close the space between paragraphs.”

4.2.6. Proof Correction Symbol and Annotations for Query: ? - “Query” - “Qu.” - “Qy.”

Overview: This symbol and the variant annotations are used in the MS to query portions of text.

Onscreen display: Displayed in the location in which they appear in the original MS.

Tooltip: “Editorial annotation querying a portion of text.”

4.2.7. Proof Correction Symbol for Substitution: /

Overview: This symbol is used in the MS to indicate that a character or word should be substituted by another.

Onscreen display: Displayed in the location in which it appears in the original MS.

Tooltip: “Editorial symbol used to indicate the substitution of one character or word for another, and sometimes to mark an insertion.”

Note: / is used for several other purposes in the MS, including signaling an insertion, indicating a new paragraph, and marking a reader’s place in the text (see Proof Correction Symbols and Annotation for New Paragraph, above, and Editorial Symbol Marking a Place in the Text, below). The function the symbol serves in its particular context is explained in the accompanying tooltip. It should also be noted that, occasionally, other indistinct textual marks are used to signal a substitution.

4.2.8. Proof Correction Annotation for Transposition: “tr.”

Overview: This annotation is used in the MS to indicate that text should be transposed (or moved from one place to another).

Onscreen display: Displayed in the location in which it appears in the original MS.

Tooltip: “Editorial instruction to transpose a portion of text from one place to another.”

Note: Transpositions are occasionally indicated using numbers, which mark the new order in which text should be read. More commonly, transpositions are signaled using a combination of arrows and encircling (see Arrows Signaling Transposition, below). It should be noted that the encoding and corresponding online display do not relocate text marked for transposition, but instead capture the editorial instructions while adhering to the material layout of the original page.

▲ 4.3. Arrows and Lines

4.3.1. Arrows Signaling Insertion: ↪

Overview: Long arrows are used in the MS to indicate where an addition written in the margin should be inserted into the body of text.

Onscreen display: Represented by ↪ at the intended point of insertion.

Tooltip: “Editorial symbol used to mark an insertion from another place on the page.”

4.3.2. Arrows Signaling Transposition: ⎰ and ⎱ plus ↪

Overview: A combination of encircling and arrows is used in the MS to indicate that a portion of text should be transposed (or moved from one place to another). The words intended for reordering are encircled and their new location marked by an arrow.

Onscreen display: Encircling is represented by enclosing the passage of text in ⎰ and ⎱ while the intended place of relocation is signaled with ↪.

Tooltip:

- For ⎰ and ⎱: “Editorial symbol used to transpose a portion of text from one place to another.”

- For ↪: “Editorial symbol used to mark an insertion from another place on the page.”

Note: Transpositions are sometimes signaled by the proof correction annotation “tr.” or by numbers (see Proof Correction Annotation for Transposition, above). It should be noted that the online display and underlying encoding do not relocate text marked for transposition, but instead capture the editorial instructions while adhering to the material layout of the original page.

4.3.3. Lines Drawn to Flag Passages for Attention: ⎰ and ⎱

Overview: Large brackets or circles drawn around portions of text are used in the MS to flag the enclosed passage for reconsideration or revision.

Onscreen display: Represented by ⎰ and ⎱ which, respectively, signal the beginning and end points of such editorial lines.

Tooltip: “Editorial line, circle, or bracket used to flag a portion of text.”

▲ 4.4. Other Editorial Notations

4.4.1. Editorial Symbols Highlighting Words or Phrases: * - [ - X

Overview: These symbols are used in the MS to point to specific places in the text. Their precise purpose is not always evident, but they generally serve to highlight particular words or parts of the page.

Onscreen display: Displayed in the location in which they appear in the original MS.

Tooltip: “Editorial symbol used to point to or highlight a particular portion of text.”

4.4.2. Editorial Symbol Marking a Place in the Text: /

Overview: Long slashes appear in the margin throughout the MS. The purpose of these slashes is somewhat unclear, but available evidence suggests that they most likely serve either to mark the place of readers while proofreading or to indicate that the manuscript section has been corrected.

Onscreen display: Displayed in the location in which they appear in the original MS.

Tooltip: “Editorial symbol used to mark the editor’s place in the text.”

Note: / is used for several other purposes in the MS, including signaling an insertion or substitution, and indicating a new paragraph (see Proof Correction Symbol for Substitution and Proof Correction Symbols and Annotation for New Paragraph, above). The function the symbol serves in its particular context is explained in the accompanying tooltip. It should also be noted that long slashes used to mark a reader’s place in the MS are displayed in transcription in a larger font size.

4.4.3. Unknown Editorial Symbol: ✧

Overview: Editorial symbols of an ambiguous or indeterminate purpose occasionally appear in the MS.

Onscreen display: Represented by ✧ and displayed in the location in which they appear in the original MS.

Tooltip: “Editorial symbol with an unknown function.”

5. Works Cited Top ⤴

Eaves, Morris, Eric Loy, Hardeep Sidhu, and Laura Whitebell. 2015. “Prototyping an Electronic Edition of Blake’s Manuscript of The Four Zoas.” 19: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century 21.

Eaves, Morris, Robert N. Essick, and Joseph Viscomi, eds. 2017. The William Blake Archive. N.p.: n.p.

Folsom, Ed, and Kenneth M. Price, eds. 2018. The Walt Whitman Archive. Lincoln, NE: Center for Digital Research in the Humanities, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Fraistat, Neil, Raffaele Viglianti, and Elizabeth C. Delinger, eds. 2018. The Shelley-Godwin Archive. College Park, MD: Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities.

Schweitzer, Ivy, dir. 2018. The Occom Circle. Dartmouth, NH: Dartmouth College.

Sutherland, Kathryn, ed. 2010. Jane Austen’s Fiction Manuscripts: A Digital Edition. Oxford: University of Oxford; London: King's College London.

![John Murray III and Anon., David Livingstone - Boat Scene (Painted Magic Lantern Slide), [1857], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND. John Murray III and Anon., David Livingstone - Boat Scene (Painted Magic Lantern Slide), [1857], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND.](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_014067_0001-carousel.jpg)

![Image of two pages from Livingstone's Field Diary XVI (Livingstone 1872h:[2]-[3]). CC BY-NC 3.0 Image of two pages from Livingstone's Field Diary XVI (Livingstone 1872h:[2]-[3]). CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000016_0003-carousel.jpg)

![David Livingstone, Map of Lakes Nyassa and Shirwa [1864?], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND; Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson, CC BY-NC 3.0 David Livingstone, Map of Lakes Nyassa and Shirwa [1864?], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND; Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson, CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000077_0001-tile.jpg)

![Image of a page segment from the Missionary Travels manuscript (Livingstone 1857bb:[47]), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/). Image of a page segment from the Missionary Travels manuscript (Livingstone 1857bb:[47]), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/missionary-travels-manuscript/textual-principles-and-encoding-practices/liv_000099_0047-article-crop.jpg)