State of the Manuscript: An Overview

Cite (MLA): Livingstone, Justin D. "State of the Manuscript: An Overview." Jared McDonald and Adrian S. Wisnicki, eds. In Livingstone's Missionary Travels Manuscript. Justin D. Livingstone and Adrian S. Wisnicki, dirs. Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. 2019. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/54655873-9da4-450f-b9af-fafb33e88517.

This essay provides an overview of the state of the manuscript of David Livingstone’s Missionary Travels. It describes the manuscript’s scope, structure, and appearance, and so identifies the major features including marginal annotations, editorial corrections, and written contributions of multiple individuals.

Introduction Top ⤴

This essay introduces the manuscript of David Livingstone’s Missionary Travels, which forms the basis of the present edition. The essay describes the scope, structure, and appearance of the manuscript as it has been preserved in the archive and examines its most notable textual features: pagination and annotation in pencil; editorial corrections in red ink; and other significant non-authorial written contributions. The following discussion facilitates consultation of Livingstone’s manuscript by this edition’s users and provides background for the more detailed analyses of Missionary Travels – in its draft and published forms – that are developed in later critical essays (Composing and Publishing Missionary Travels [1], Missionary Travels in Pen & Print [1]).

Scope, Structure, and Appearance Top ⤴

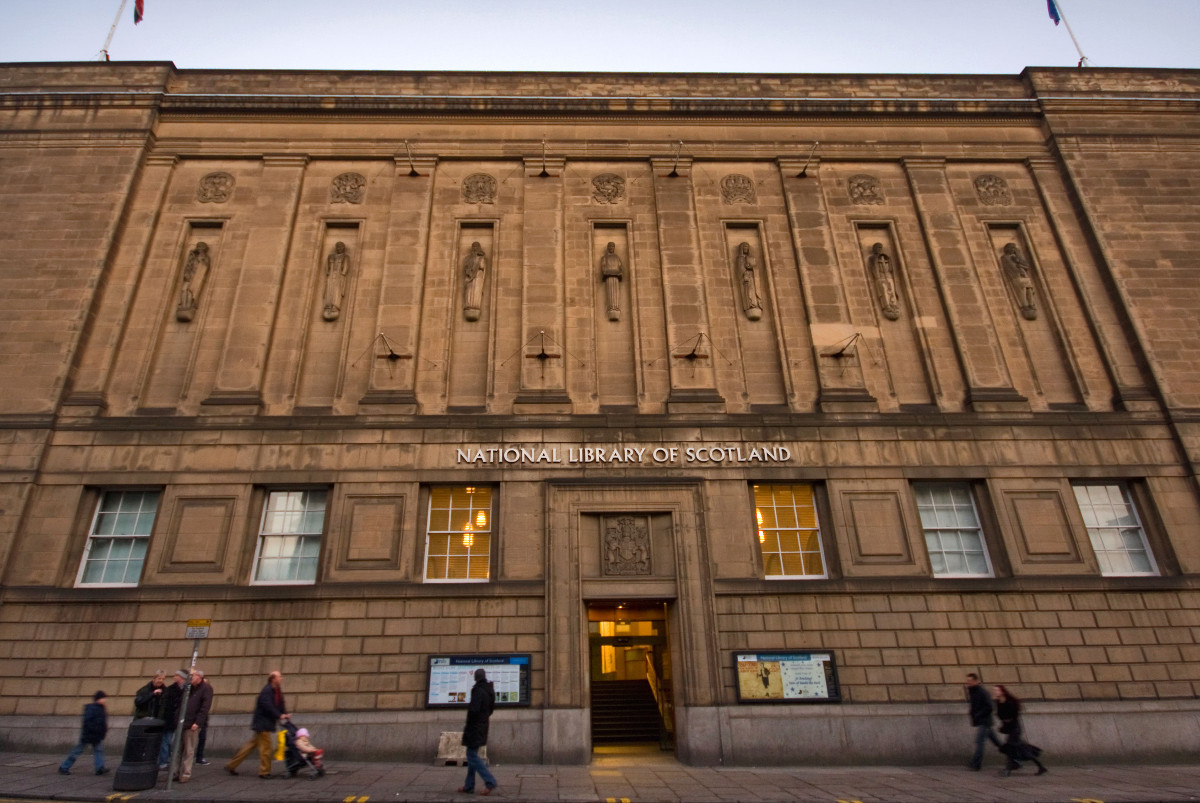

The draft manuscripts of Missionary Travels consist primarily of three volumes in the National Library of Scotland (NLS) (Livingstone 1857bb, 1857cc, 1857dd). Initially written as loose leaves, the pages were bound subsequently by either the publisher, John Murray, or a later archivist. Together the volumes amount to 1129 pages of handwritten text: the first volume consists of 381 pages, the second volume, 476 pages, and the third volume, 272 pages. These bound manuscripts make up the core material of this digital edition.

The edition, however, also includes a number of manuscript fragments separated from the major volumes. The NLS holds a three-page “suppressed preface” that Livingstone wrote for the private eyes of John Murray and an additional three loose leaves, while a one-page manuscript resides at the David Livingstone Centre Blantyre (1857ff, 1857d, 1857c).

The National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland. Copyright Livingstone Online. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The National Library of Scotland is the primary archival contributor to the present edition. The vast majority of manuscripts included here are held in the library's John Murray Archive.

Far from Livingstone’s place of composition, there are also three folios in the Brenthurst Library in Johannesburg, South Africa. These folios appear to have been separated from the manuscript body by Livingstone himself, who gifted them to a Church of Scotland minister from his native South Lanarkshire. The final page is inscribed with the words: “Leaves from Manuscript of Dr Livingstone’s Travels in Africa given by the author to Dr Keith of Hamilton” (Livingstone 1857b).

The vast majority of extant documents are gathered in this edition, although there are several manuscript fragments not included which are held primarily in the Livingstone Museum, Zambia (Cunningham and Clendennen 1979:265). Combined, all the manuscript pages amount to a little over three quarters of the published text. The first two volumes are continuous without major omissions, but the third volume is in a more incomplete state.

Together, the three volumes are divided into sections which are numbered sequentially from I to XLVIII and which are normally between twenty and thirty pages in length. The sequence is unbroken until the end of section XXXIX. From this point, a number of gaps appear: sections XL, XLII, XLV, and XLVI are missing. The third volume is also unfinished, lacking the final six pages that appear in the published Missionary Travels. It is likely, then, that the manuscript is missing a section XLIX, which would correspond to the concluding pages of the printed book.

| (Left; top in mobile) Image of a page from the Suppressed Preface to Missionary Travels (Livingstone 1857ff:[1]). Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. (Right; bottom) Image of a page from the Missionary Travels manuscript (Livingstone 1857bb:[307]). Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. The two pages displayed here illustrate, respectively, the historical value and key characteristics of the Missionary Travels manuscript. The page on the left (top in mobile) shows a portion of draft text that was excluded from the published version of the book and has not been widely available for study until the release of this edition. The page on the right (bottom in mobile) shows the sorts of editorial corrections (e.g., textual insertions, deletions, and marginal annotations) that are recurring features of the manuscript. |

It is worth noting that the divisions of the manuscript do not correspond directly to those of the published Missionary Travels. The manuscript consists of forty-eight sections, whereas the printed book divides into thirty-two longer chapters. In fact, the numerical sequence in the three volumes was probably not designed to indicate chapter breaks, but rather to mark portions of manuscript as they were sent to readers for comments and then to the printers, where they would be set in type as galley proofs for copyediting.

The Missionary Travels manuscript is not the most impenetrable of Livingstone’s documents. Written in the knowledge that others would be consulting it for editorial purposes, the manuscript is not as demanding on the reader as Livingstone’s less legible notebooks and diaries composed in the field (Wisnicki 2017, Wisnicki and Ward 2017, Ward and Wisnicki 2018). However the document is very much a working draft and presents the challenges of reading a manuscript in revision, in which insertions from the margins and verso, transposed passages, and textual corrections are recurring features.

Pagination and Annotations in Pencil Top ⤴

The written contributions of multiple hands to the Missionary Travels manuscript are immediately noticeable. These include at least two to three individuals who added the manuscript’s pagination in pencil across the three volumes. With the exception of pages [84]-[251] in the third volume (and some shorter sections, such as pages [211]-[228] in the first volume), there are in fact two sets of page numbers and occasionally three.

One of these sets, appearing in the manuscript header, consistently numbers each volume from beginning to end. Since this sequence proceeds continuously, even where there are evidently missing sections of manuscript, it was almost certainly added by a later archivist after the documents had been bound in volume form. In the transcription, this hand is designated “Unknown Hand 1”; aside from very occasional archival annotations (see, e.g., Livingstone 1857c:[1] and 1857dd:[2]-[4]), this hand’s role is limited to pagination.

![Image of a page segment the Missionary Travels manuscript (Livingstone 1857c:[1]), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, University of Glasgow Photographic Unit, and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). Image of a page segment from the Missionary Travels manuscript (Livingstone 1857c:[1]), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, University of Glasgow Photographic Unit, and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/missionary-travels-manuscript/state-the-manuscript-overview/liv_000103_0001-article-crop.jpg)

Image of a page segment from the Missionary Travels manuscript (Livingstone 1857c:[1]), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, University of Glasgow Photographic Unit, and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The segment displayed here includes an annotation in pencil – most likely added by a later archivist – that links the manuscript page to the corresponding page in the published book. Elsewhere on the page, the same archivist has added penciled pagination and a note identifying the manuscript's author as David Livingstone. The segment shown here also includes an inked comment by Livingstone instructing a copyeditor or compositor to insert supplementary material following this portion of text.

The second set of page numbers, which can appear in the header, footer, or left hand margin, is more likely to date to the time of writing. This much can be inferred from interruptions in the numbering (see Livingstone 1857bb:[211]-[228]), and some inconsistencies that are presumably the result of portions of manuscript being reordered or discarded during composition (see Livingstone 1857bb:[331]-[332] where the sequence jumps from “278” to “73”). This second numerical sequence also begins again from page “1” at a number of section breaks, a feature that probably indicates that the sequence predates the binding of the three volumes (see Livingstone 1857bb:[190]; 1857cc:[168], [263], [335], [407]; 1857dd:[45], [252]).

![Blantyre Factory, Scotland. Image from Magic Lantern Slides, Livingstone and Stanley Series (John Murray c.1900:[2]). Copyright National Library of Scotland . Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/). Blantyre Factory, Scotland. Image from Magic Lantern Slides, Livingstone and Stanley Series (John Murray c.1900:[2]). Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/missionary-travels-manuscript/state-the-manuscript-overview/liv_014076_0002-article-1200.jpg)

Blantyre Factory, Scotland. Image from Magic Lantern Slides, Livingstone and Stanley Series (John Murray c.1900:[2]). Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. Livingstone began working in the Blantyre cotton mill when he was ten years old. The Livingstone family home in Blantyre is now the David Livingstone Birthplace Museum (until recently known as the David Livingstone Centre). Among the museum’s substantial manuscript collection, much of it published by Livingstone Online, is a one-page fragment of the Missionary Travels manuscript that is included in the present edition (also see previous image).

In the present edition, the project team has proceeded on the basis that the original pagination (the second set of numbers cited above) was added by one or another of the individuals whose light pencil annotations appear throughout the volumes and who offer occasional comments and corrections. That there were a number of such persons, either readers employed by John Murray or compositors working for the printer William Clowes, is evident from the fact that their signatures periodically appear in the margins.

Among the names that can be determined with relative certainty are Berry, Bristow, Chester, Dennett, Goodby, Mead, Powell, Richards, Robinson, Sedgwick, Sorell, Wheeler and Wilkes. However, since the interventions of these individuals are limited mainly to minimal markup they are almost entirely indistinguishable. In light of this, these individuals are identified collectively in the transcription as “Unknown Hand 2.”

Editorial Corrections in Red Ink Top ⤴

The manuscript also contains more substantial annotations in red ink. These are almost certainly the work of a single person – probably the primary literary reader working for John Murray. It is likely that this individual (labelled “Unknown Hand 3” in the edition) was John Milton, an experienced reviser who spent 143 hours working on Missionary Travels (Fraser 1996:33). These editorial interventions begin to appear in the first volume on page [82]; with the exception of pages [200]-[229], which are free of annotations in red, they continue to appear in varying degrees of frequency across the rest of the volume.

![Image of a page segment from the Missionary Travels manuscript (Livingstone 1857bb:[114]), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/). Image of a page segment from the Missionary Travels manuscript (Livingstone 1857bb:[114]), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/missionary-travels-manuscript/state-the-manuscript-overview/liv_000099_0114-article-1200-crop.jpg)

Images of two page segments from the Missionary Travels manuscript (Livingstone 1857bb:[105],[114]), detail in both cases. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. The segments above exhibit the editorial mark up in red ink – probably by John Milton, a literary editor employed by the John Murray publishing house – that appears across the first two volumes of the Missionary Travels manuscript. The top segment shows a marginal note querying Livingstone's intended meaning. The bottom segment shows the proof correction mark for "transposition" along with a combination of encircling and an arrow that signals the portion of text to be transposed and the location to which it should be moved.

The work of the “red ink man,” as Livingstone called him (1857k), continues into the second volume until page [166]. At this point it disappears altogether. A number of corrections in dark ink between pages [312] and [325] are in a similar script, but one that cannot be determined decisively to be the work of the same hand. In the third volume, the annotations of the “red ink man” are seen only in the opening two pages. These folios, however, actually belong to an earlier point in the manuscript (they should follow page [196] in the first volume) and have clearly been misplaced in the binding process.

From mid-way through the combined volumes, then, the “red ink man” seems to have discontinued working on the Missionary Travels manuscript. This may have been the result of Livingstone’s objections to editorial interference, which he freely voiced to John Murray (see Composing and Publishing Missionary Travels [2]).

Additional Written Contributions Top ⤴

The contributions of three other hands can be distinguished in the manuscript. One of these is the author of the inscription mentioned above, which appears on the Brenthurst folios. It is possible that this inscription was written by the recipient of the gifted manuscript himself, Rev. Dr. P. H. Keith, who was a Presbyterian clergyman and President of the town of Hamilton’s “Orphan and Charity School Association” (Macpherson 1862:85, 87). However, this cannot be established with any certainty and the inscription could equally have been written by another party. For that reason, this hand is designated “Unknown Hand 4” in the transcription.

The contributions of the other two hands are more significant. One set belongs to Charles Livingstone, the explorer’s brother, whose role in the composition of Missionary Travels has not to date received due critical attention. Charles Livingstone was, however, the primary scribe for around 50% of the third volume (see Livingstone 1857dd:[83]-[251]). His involvement in the book can be determined by the character of his handwriting, but it is also confirmed by internal manuscript evidence. For instance, David Livingstone leaves an editorial note referring to material written in “my brothers [sic] hand” on one leaf of the manuscript (1857dd:[183]).

![Image of a page segment from the Missionary Travels manuscript (Livingstone 1857dd:[183]), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/). Image of a page segment from the Missionary Travels manuscript (Livingstone 1857dd:[183]), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/missionary-travels-manuscript/state-the-manuscript-overview/liv_000101_0183-article-1200-crop.jpg)

Images of page segments from the Missionary Travels manuscript (Livingstone 1857dd:[97], [252], [183]), detail in all cases. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. These three segments show several of the hands that appear in the Missionary Travels manuscript. The first segment (top left; top in mobile) presents text written by Charles Livingstone. The second segment (right; middle) shows text by David Livingstone’s copyist (who was possibly Wilbraham Taylor) as well as a brief marginal addition by Livingstone. The third segment (at bottom) offers a note in Livingstone’s hand providing instructions to this copyist.

The written contributions of the other unnamed individual appear only in the final twenty-one pages of the third volume (Livingstone 1857dd:[252]-[272]). Since these folios duplicate the portion of manuscript that immediately precedes them (see Livingstone 1857dd:[238]-[251]), they are presumably the work of an amanuensis producing clean copy. It is likely that these pages were written by one of Livingstone’s “next door neighbours,” who apparently “recopied” parts of the manuscript for him (1857t). The copyist may well be Mr Wilbraham Taylor, a neighbour who assisted Livingstone by liaising with the publisher to arrange for the delivery and receipt of literary matter (1857q, 1857t).

Conclusion Top ⤴

This edition brings together Livingstone’s three handwritten volumes and other fragments to provide the fullest possible manuscript record of Missionary Travels. The result is an unusually complete and well-preserved draft of a nineteenth-century travel narrative, that provides evidence of both its author’s composition practices and its publisher’s editorial practices as the work evolved towards the printed version. This essay has sought to describe the significant and sometimes complex features of Livingstone’s Missionary Travels manuscript; the state of the manuscript as it now appears derives both from its status as a working draft, bearing the traces of the publication process, and from its later archival history.

Works Cited Top ⤴

Clendennen, G. W., and I. C. Cunningham. 1979. David Livingstone: A Catalogue of Documents. Edinburgh: National Library of Scotland.

Fraser, Angus. 1996. “A Publishing House and its Readers, 1841-1880: The Murrays and the Miltons.” Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 90 (1): 4-47.

Livingstone, David. 1857b. Fragment of Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa (Part III). Jan.-Oct. 1857. MS. 023. Brenthurst Library, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Livingstone, David. 1857c. Fragment of Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa (Part III). Jan.-Oct. 1857. 834. David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1857d. Fragment of Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa (Part III). Jan.-Oct. 1857. MS. 20312, f. 198. National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1857k. Letter to John Murray III. 6 Apr. 1857. MS. 42420, ff. 12-15. National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1857q. Letter to John Murray III. 30 May 1857. MS. 42420, ff. 37-40. National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1857t. Letter to John Murray III. 17 June 1857. MS. 42420, ff. 51-56. National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1857bb. Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa (Part I). Jan.-Oct. 1857. MS. 42428. National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1857cc. Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa (Part II). Jan.-Oct. 1857. MS. 42429. National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1857dd. Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa (Part III). Jan.-Oct. 1857. MS. 10702. National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1857ff. Suppressed Preface to Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa. Jan.-Oct. 1857. MS. 42427, ff. 1-3. National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Macpherson, Angus. 1862. Hand-Book of Hamilton, Bothwell, Blantyre and Uddingston. Hamilton: WM. Naismith.

Ward, Megan, and Adrian S. Wisnicki, dirs. 2018. Livingstone’s Final Manuscripts (1865-1873): Diaries, Journals, Notebooks, and Maps: A Critical Edition. First edition. In Livingstone Online: Illuminating Imperial Exploration, directed by Adrian S. Wisnicki, Megan Ward, Anne Martin, and Christopher Lawrence. New version, second edition. College Park, MD: University of Maryland Libraries.

Wisnicki, Adrian. S., dir. 2017. Livingstone’s 1871 Field Diary: A Multispectral Critical Edition. Updated version. In Livingstone Online: Illuminating Imperial Exploration, directed by Adrian S. Wisnicki, Megan Ward, Anne Martin, and Christopher Lawrence. New version, second edition. College Park, MD: University of Maryland Libraries.

Wisnicki, Adrian S., and Megan Ward, dirs. 2017. Livingstone’s 1870 Field Diary and Select 1870-1871 Manuscripts: A Multispectral Critical Edition. First edition. In Livingstone Online: Illuminating Imperial Exploration, directed by Adrian S. Wisnicki, Megan Ward, Anne Martin, and Christopher Lawrence. New version, second edition. College Park, MD: University of Maryland Libraries.

![John Murray III and Anon., David Livingstone - Boat Scene (Painted Magic Lantern Slide), [1857], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND. John Murray III and Anon., David Livingstone - Boat Scene (Painted Magic Lantern Slide), [1857], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND.](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_014067_0001-carousel.jpg)

![Image of two pages from Livingstone's Field Diary XVI (Livingstone 1872h:[2]-[3]). CC BY-NC 3.0 Image of two pages from Livingstone's Field Diary XVI (Livingstone 1872h:[2]-[3]). CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000016_0003-carousel.jpg)

![David Livingstone, Map of Lakes Nyassa and Shirwa [1864?], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND; Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson, CC BY-NC 3.0 David Livingstone, Map of Lakes Nyassa and Shirwa [1864?], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND; Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson, CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000077_0001-tile.jpg)

![Image of a page from the Suppressed Preface to Missionary Travels (Livingstone 1857ff:[1]). Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/). Image of a page from the Suppressed Preface to Missionary Travels (Livingstone 1857ff:[1]). Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/missionary-travels-manuscript/state-the-manuscript-overview/liv_003010_0001-article-1200.jpg)

![Image of a page from the Missionary Travels manuscript (Livingstone 1857bb:[307]). Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/). Image of a page from the Missionary Travels manuscript (Livingstone 1857bb:[307]). Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/missionary-travels-manuscript/state-the-manuscript-overview/liv_000099_0307-article-1200.jpg)

![Image of a page segment from the Missionary Travels manuscript (Livingstone 1857bb:[105]), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/). Image of a page segment from the Missionary Travels manuscript (Livingstone 1857bb:[105]), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/missionary-travels-manuscript/state-the-manuscript-overview/liv_000099_0105-article-1200-crop.jpg)

![Image of a page segment from the Missionary Travels manuscript (Livingstone 1857dd:[97]), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/). Image of a page segment from the Missionary Travels manuscript (Livingstone 1857dd:[97]), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/missionary-travels-manuscript/state-the-manuscript-overview/liv_000101_0097-article-1200-crop.jpg)

![Image of a page segment from the Missionary Travels manuscript (Livingstone 1857dd:[252]), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/). Image of a page segment from the Missionary Travels manuscript (Livingstone 1857dd:[252]), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/missionary-travels-manuscript/state-the-manuscript-overview/liv_000101_0252-article-1200-crop.jpg)