Composing & Publishing Missionary Travels (1)

Cite (MLA): Livingstone, Justin D. "Composing & Publishing Missionary Travels (1)." Jared McDonald and Adrian S. Wisnicki, eds. In Livingstone's Missionary Travels Manuscript. Justin D. Livingstone and Adrian S. Wisnicki, dirs. Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. 2019. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/39bd34d1-4c55-4c2e-abe3-433109b1a645.

This page, the first of a two-part essay, traces the creation of Missionary Travels at the hands of author and publisher. It examines the draft manuscript and associated publishing correspondence for what they reveal about both David Livingstone’s composition practices and the methods of the John Murray publishing house. The essay contends that the making of Missionary Travels was characterised by a complex circulation of manuscript and print in which galley proofs began to be distributed and revised even while the composition of new material was ongoing. The essay also addresses a key altercation between Livingstone and his publisher by arguing that, although the production of Missionary Travels was highly collaborative, Livingstone made considerable effort to retain literary authority over his book. Read the second part of the essay here.

Introduction Top ⤴

In the popular imagination, the European exploration of the globe was once – and often still is – conceived of as primarily a heroic and adventurous endeavour. Such a notion is of course no pure fabrication; it registers the undoubted physical demands that explorers faced in travelling over vast distances in pursuit of their expeditionary agendas. Scholarship, however, has progressively complicated this characterisation, assessing exploration instead as a "concept and a practice" with complex "cultural, social, and political valences" (Kennedy 2014:1). In contrast to the reductive terms of the overarching heroic model, nineteenth-century exploration was an enterprise that intersected with scientific objectives, commercial aspirations, religious intentions, imperial expansion, and of course personal ambition.

Following the work of Felix Driver, scholars have become interested in the "cultures of exploration," a term that signals the multiple contexts in which exploration operated and "the wide variety of practices at work in the production and consumption of voyages and travels" (2001:8). More specifically, a body of research has directed attention to exploration's literary culture. In the nineteenth century, significant expeditions were expected to deliver their findings through the printed word in the form of official reports, scientific papers, popular articles, and major travelogues (Cavell 2008, Driver 2013). For domestic audiences, these published texts were the primary means of information both about expeditions and the distant locations through which explorers journeyed. As with other European projects overseas – notably the missionary enterprise – exploration was almost indivisibly linked to the writings it produced.

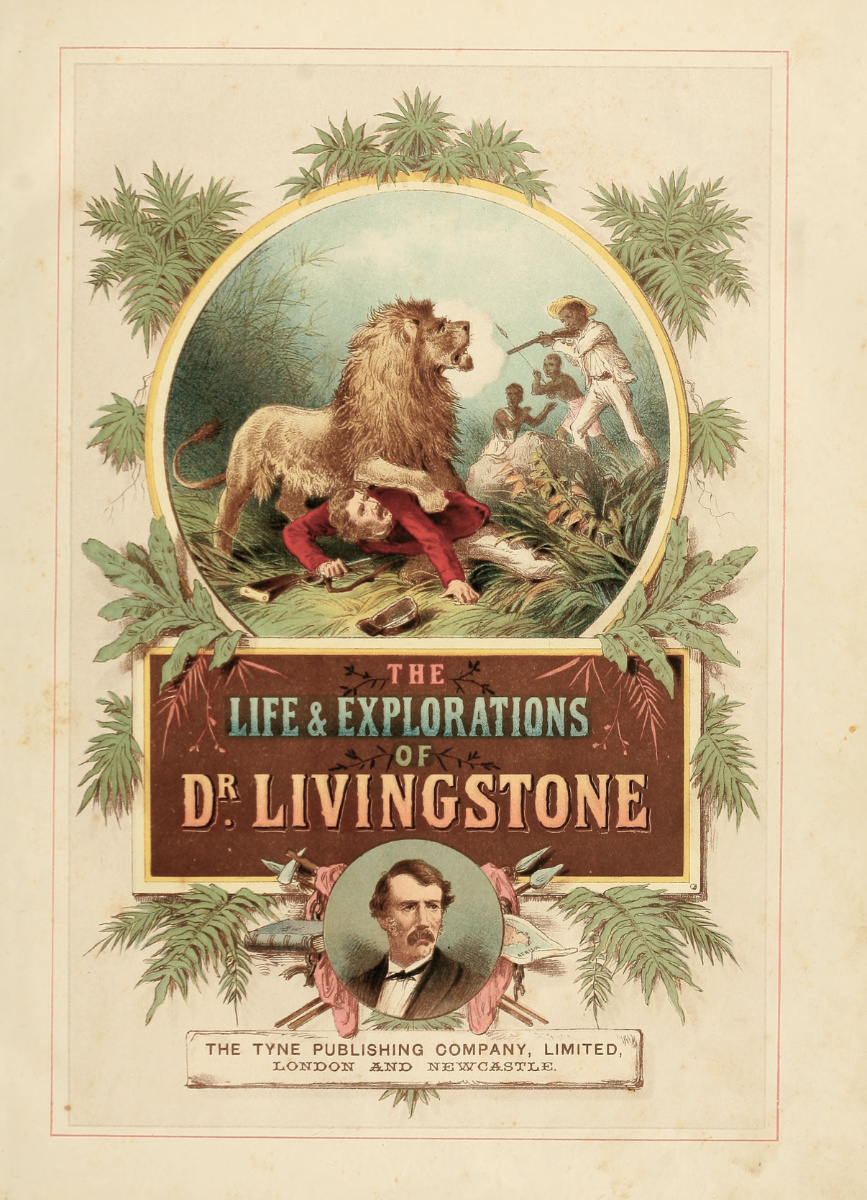

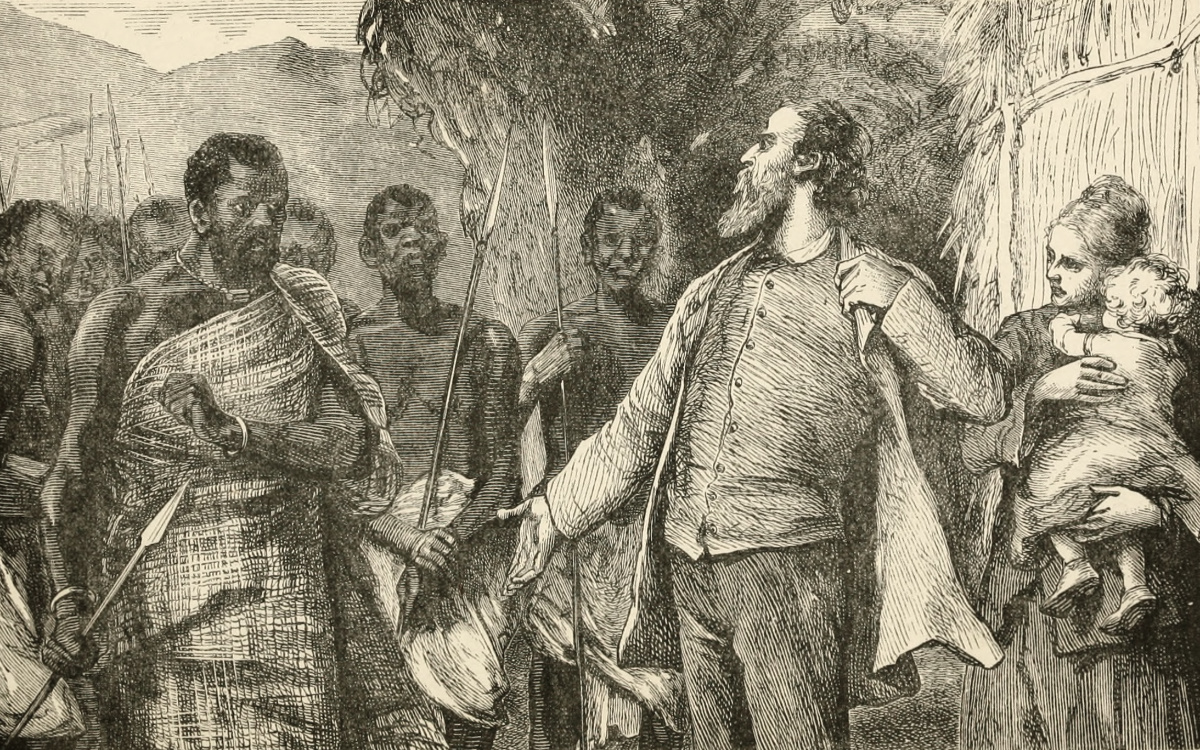

Frontispiece. Illustration from John S. Roberts, The Life and Explorations of David Livingstone L.L.D. (London: John G. Murdoch, 1870). Courtesy of the Internet Archive. Although exploration was a scientific enterprise involving official reports and extensive documentation, geographical expeditions were also celebrated in popular culture. This frontispiece provides an example of how Livingstone – and African exploration more broadly – were mediated to the public in popular biographies.

The explosion of print culture in the nineteenth century ensured that mid-Victorian expeditions produced an abundance of published narratives, notably about the Arctic, Australia, and the African continent. While such texts have long been analysed as non-transparent documents open to critical reading (Brantlinger 1988, Youngs 1994), studies have increasingly attended to the means by which published travelogues were produced. Narratives of exploration tend to be regarded as the definitive word on the time in the field, but they were highly mediated records worked up by authors themselves and by agents of the publishing industry.

As Ian MacLaren has argued, it is crucial to disentangle the journey from "exploration to publication," the "evolution" of field notes into books, and the transformation from explorer into author (1994:43). Studies of exploration that follow book-historical approaches thus explore "two journeys, the one geographical, and the other authorial": the journey of the explorer in the field and the journey of those "travels into print" (Keighren, Withers, and Bell 2015:18; also see Finkelstein 2003, Craciun 2016).

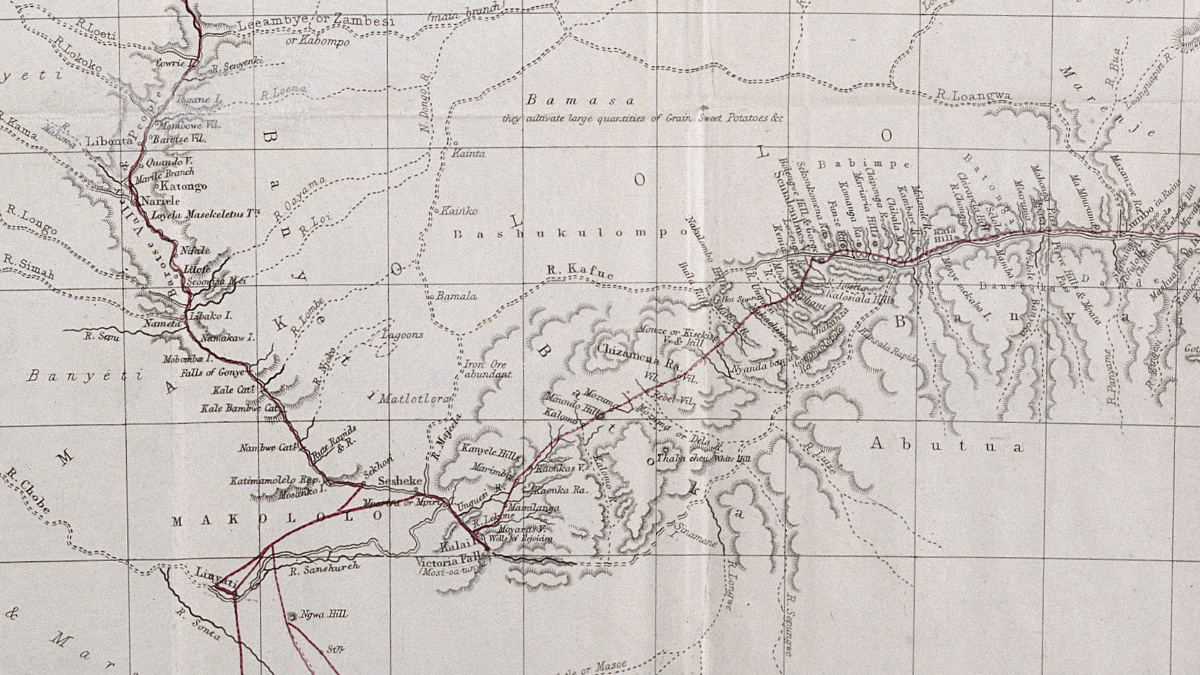

Detailed Map of the Revd. Dr. Livingstone's Route Across Africa, by John Arrowsmith. Fold out map from Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa (Livingstone 1857aa:n.p.), detail. Copyright Wellcome Library, London. As relevant copyright Dr Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. Publishing expeditionary narratives involved the expertise of multiple individuals. John Arrowsmith, one of Britain’s leading cartographers, used Livingstone’s written records to prepare this map along with another that traces the route of the transcontinental journey. Both were included in Missionary Travels.

This essay traces the creation of David Livingstone's Missionary Travels (1857) at the hands of both author and publisher. It investigates the relationship between Livingstone and John Murray III (the third in a publishing dynasty; hereafter "John Murray"), an alliance of mutual advantage that turned a missionary and traveller into a bestselling writer. Examining the holograph of Missionary Travels and associated publishing correspondence, the essay addresses both Livingstone's composition practices and the Murray firm's methods as the two men collaborated on producing a narrative of a transcontinental expedition.

In discussing the making of Missionary Travels, the aim here is to disclose the stages of the process more fully than has been achieved by previous scholarship. The essay addresses the overlapping phases of composition and correction of manuscript as well as the production and revision of proofs, to reveal a complex circulation of manuscript and print. Situating Livingstone in an industry of travel publishing in which editorial intervention was conventional practice, this analysis also traces Livingstone's efforts to regulate interference. Although the Murray firm habitually exerted control over the literary journey to print, the essay ultimately reveals the means by which Livingstone sought to manage the process and retain jurisdiction over his narrative.

Publishing with John Murray Top ⤴

The correspondence between Livingstone and Murray on the subject of Missionary Travels dates to early January 1857, shortly after Livingstone's return to Britain following his transcontinental journey (1852-56). Their early exchanges, which began while Livingstone's plans were still in formation, cast light on an unusual – but remarkably successful – literary partnership.

When Livingstone arrived in London, he found that he had already become a national celebrity. His travels between the west and east African coasts, in pursuit of a navigable "highway" into the interior, had been widely publicised by the Royal Geographical Society and the press. Lecture invitations proliferated and the expectation of a major publication quickly mounted. It is likely, however, that Livingstone had intended to write a narrative about his experiences in central and southern Africa for quite some time before his meteoric rise to fame. The extent and detail of his record keeping throughout the 1852-56 expedition suggest that he was methodically documenting his activities and observations with a view to publication (e.g., Schapera 1960a, 1963).

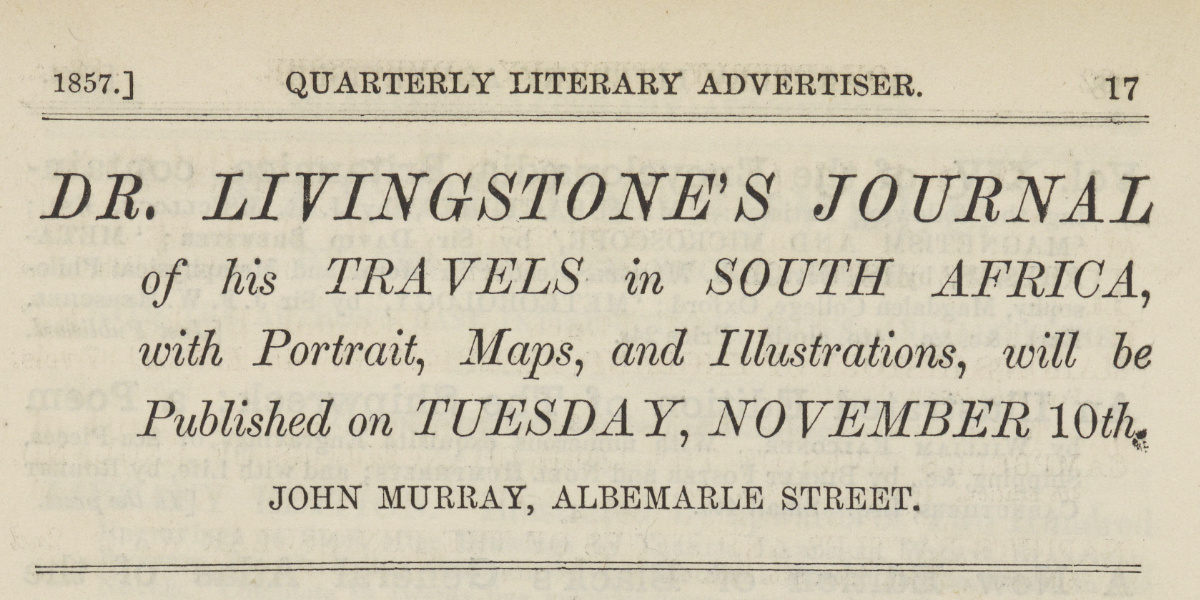

(Top) Trade Advert for Dr. Livingstone's Journal of his Travels in South Africa, Quarterly Review, 102 (July 1857-October 1857): September 1857, 17, detail. (Bottom) Trade Advert for Dr. Livingston's Missionary Journals and Researches in South Africa, Quarterly Review, 101 (January 1857-April 1857): March 1857, 22, detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. John Murray heightened public anticipation for Livingstone's Missionary Travels by releasing regular trade adverts in the months preceding the book's publication. Since Livingstone took longer to complete the book than anticipated, Murray also used these adverts to retain public interest and to contest other publishers who took advantage of the delay by publishing "unofficial" narratives of Livingstone's travels.

Livingstone had actually been writing abundantly since his early period as a missionary to the BaTswana in the 1840s. He was not only a prolific correspondent who produced an enormous corpus of letters from the field (e.g., Schapera 1959, 1961), but the author of a series of papers and reports (Schapera 1974:xi): some of these materials appeared in his name and others were printed anonymously; more appeared posthumously while a number have only been published in the last decade or so by Livingstone Online. Together, his early articles on topics including missionary strategy, race relations, and southern African geography suggest that his later venture into publishing with Missionary Travels was long in the making.

Publishing a memoir of the mission field was becoming standard practice for missionaries in the mid-Victorian period (Johnston 2003). Some of the more celebrated figures of the London Missionary Society (LMS) had done just that. John Williams, a missionary based in the South Pacific, had published his Narrative of Missionary Enterprises in the South Sea Islands in 1837, while John Philip, one of the society's pioneers in southern Africa, had published his Researches in South Africa a decade earlier in 1828. Livingstone was certainly influenced by the latter as well as the work of his own father-in-law, Robert Moffat, who had written Missionary Labours in Southern Africa (1842) during a furlough in Britain. As Chris Wingfield observes, Livingstone was in some respects conforming "to a prototype of the heroic male missionary" by "pursuing a career path that had been established by a previous generation of LMS missionaries" (2012:117-18).

Now Then, If You Will, Drive Your Spears to My Heart. Illustration from David J. Deane, Robert Moffat the Missionary Hero of Kuruman, second edition (New York, Chicago: Fleming H. Revell, c.1880), 61. Courtesy of the Internet Archive. This image, which dramatises the dangers of intercultural encounter, highlights an established tradition of representing mission as a heroic enterprise; this tradition would contribute to the crafting of Livingstone's public persona.

Yet, although Livingstone was influenced by earlier missionary-authors, he did not fully conform to the pre-existing pattern. Both Williams and Moffat had published their works with John Snow, the publisher of numerous missionary and religious writings including the LMS Missionary Magazine and Chronicle. In publishing with John Murray, by contrast, Livingstone attached himself to a press that specialised in travel narratives rather than missionary memoirs.

John Murray was one of Britain's most reputable publishers. Established in 1768, his firm went on to publish works by a host of major authors including Jane Austen, Lord Byron, Walter Scott, and Charles Darwin (Zachs 1998, Keighren, Withers, and Bell 2015). While the firm's output was vast, ranging from the literary to the scientific, it developed a particular emphasis on travel and soon established itself as the leading British publisher of expeditionary literature. For Livingstone, publishing with Murray was a critical choice; it marked a departure from his missionary predecessors, an attempt to negotiate a larger market, and a determination to contribute to the literature of exploration.

If Livingstone was writing a travel narrative, however, he didn't give up the book's status as missionary memoir. In Murray's Copies Ledger and Day Books, entries relating to Livingstone's anticipated publication are recorded under variant titles such as: "Dr Livingston's Exploratory Journeys in South Africa," "Livingston's South Africa," "Livingstone's Travels," "Livingstone's Journals," and "Livingstone's Africa" (Murray 1846-1876:422, 424; Murray 1853-1857:364, 380, 383; Murray 1857-1861:1). The eventual title of the book, by contrast, clearly signals the credentials of a missionary as well as that of a geographical traveller: Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa. The record of Livingstone's time in the field integrated elements of the missionary narrative into an ambitious work of central and southern African exploration.

The Livingstone-Murray Alliance Top ⤴

Nevertheless, the arrangement with Murray was not simply the result of strategic selection on Livingstone's part. As the epistolary record shows, their affiliation was equally the publisher's initiative. John Murray pursued Livingstone eagerly as a prospective author, approaching him in person shortly after his return to Britain and following this up soon afterward with a formal offer by letter.

On 5 January 1857, Murray took the chance, as he expressed it, to "put into writing the proposal which I made when I had the pleasure to see you for the publication of your work." Murray spied a lucrative opportunity, offering generous terms reserved for his more esteemed authors. Not only was he "quite willing to take upon myself the whole cost of the publication including engraving of maps, plates & other incidental expenses," but he was prepared to offer a liberal "two thirds of the profits of every Edition" (Murray 1846-1858:274).

The publisher's usual practice was "to give one half of the proceed to the author," but in a case like Livingstone's, Murray was prepared to go further "in consideration of the probable value & interest of your work & the certain popularity which it will attain" (Murray 1846-1858:275). These terms, Murray told Livingstone, were the same granted to luminaries such as George Grote and Austen Henry Layard, and would prove more advantageous than parting with the copyright outright for a fixed price. Murray aimed to convince Livingstone by offering conditions that best served his client's long-term interests. Arguing in favour of a royalties system, which was not yet widespread in Britain, he assured Livingstone that it would "secure to you a fair share of advantage as long as your book continues in demand" (Murray 1846-1858:275; also see Finkelstein and McCleery 2013:76, 80).

Lord Byron and Sir Walter Scott at No. 50 Albemarle Street, 1815. Painting by L. Werner (c.1850). Copyright John R. Murray. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. From 1812 onward, the John Murray publishing house was based at 50 Albemarle Street in Mayfair, London. The drawing room, pictured above, was the firm’s social and intellectual centre. Livingstone was a regular visitor at this address in 1857 as he worked on Missionary Travels.

Livingstone may have been weighing his options because two weeks later, on 19 January 1857, Murray wrote to him again to revisit the deal. Concerned that he had not yet had a response and that, according to Sir Roderick Murchison, Livingstone was receiving offers from "other persons," Murray decided to improve on his offer. In case Livingstone had found the initial proposal to be "not sufficiently definite," Murray now volunteered a considerable down payment of two thousand guineas (Murray 1846-1858:277).

Since an advance on profits was not characteristic of Murray's terms, he was clearly making an exception to his usual practice in securing prospective authors (Keighren, Withers, and Bell 2015:24). In fact, Murray showed considerable personal attention, stressing that he was available to discuss the publication at the author's convenience and assuring Livingstone that the firm would provide support in bringing the narrative to print: "Should you need any literary assistance or advice in the preparations of your M.S.S. for the press I should have no difficulty in procuring it for you" (Murray 1846-1858:278; also see Henderson 2015).

Murray's direct approach to Livingstone is certainly striking. The publisher received a steady stream of proposals and manuscripts, and had little need to solicit authors. But he clearly did not want to miss the commercial opportunity of the season. It is worth pointing out that in some respects Livingstone was an unusual author for a Murray travel book. From 1813 John Murray was the official publisher for the Admiralty and the Board of Longitude, and from 1831 the publisher of the Royal Geographical Society's journal. Although there was variety amongst Murray's travel authors, these institutional affiliations ensured that many of his writers were members of "official" expeditions who had travelled with the directives of Britain's naval and geographical establishments (Keighren, Withers, and Bell 2015:6-7, 25).

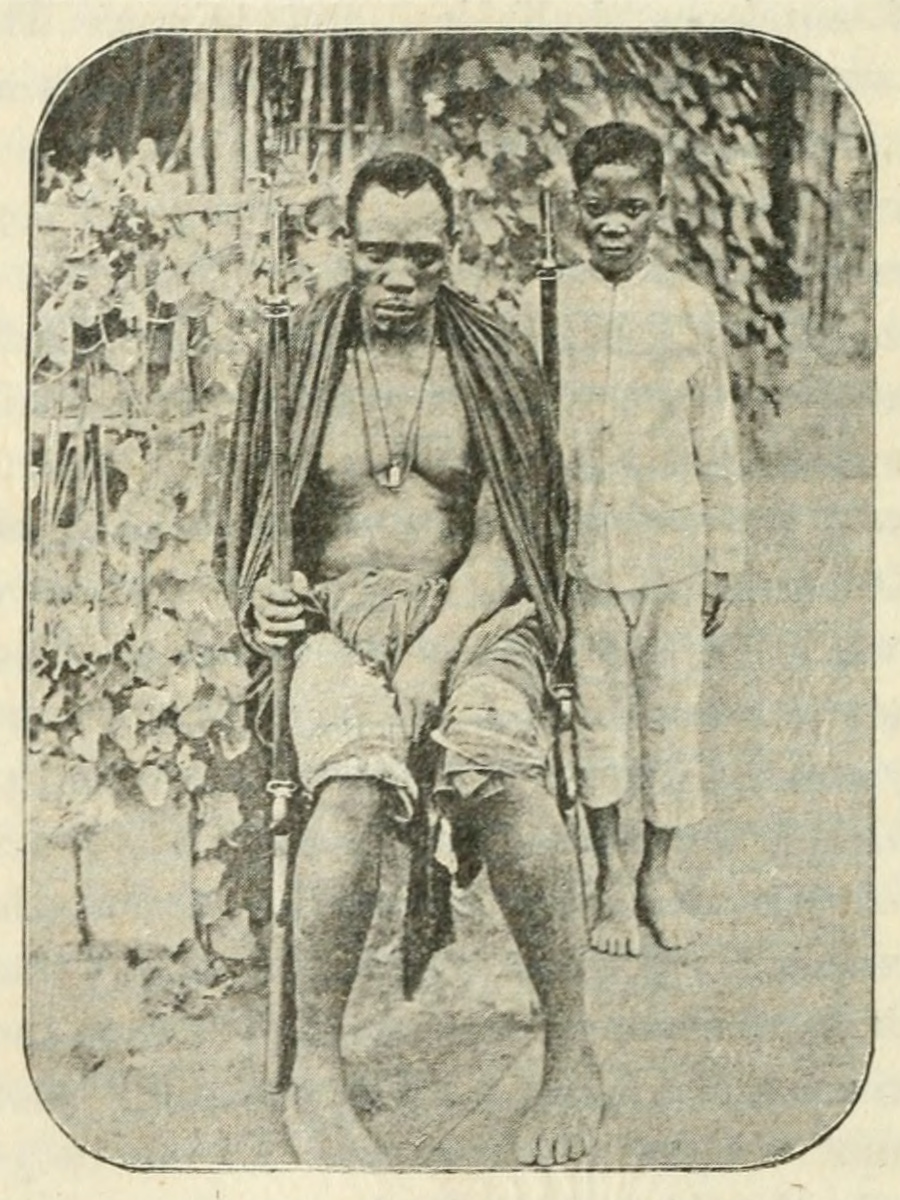

A Ma-kololo. Illustration from H. H. Johnston, Livingstone and the Exploration of Central Africa (London: George Philip & Son, 1891), 78. Courtesy of the Internet Archive. Although Livingstone’s transcontinental expedition was supported by the leader of the Makololo, Sekeletu, members of the Makololo rarely appear in illustrated or pictorial form in contemporaneous and posthumous Livingstone biographies. The photograph above represents a rare deviation from the general trend. However, Johnston's caption ("A Ma-kololo") both ignores one of the individuals and presents the other as only a generic representative of the Makololo group as a whole, and so follows patterns of representation for non-European peoples that appear in many imperial-era works. The corresponding narrative text does not identify the two individuals or indicate if either travelled with Livingstone.

Livingstone's cross-continental expedition was of a quite different sort. First, he was an agent of a missionary society and, second, he had not travelled under instruction or with the financial support of any scientific institution. Rather, Livingstone was the lone European in an expedition made possible by an alliance with the Makololo, an ethnic group who had established a state in south-central Africa and who were interested in extending trade routes to the west and east coasts. Travelling effectively as an "Nduna" – or officer – of the Makololo leader Sekeletu (Ross 2002:xiv, 89), Livingstone had engaged in a kind of journey that fell outside the parameters of travel that would usually result in a Murray narrative.

Yet, although Livingstone was an atypical explorer-author in some respects, he was authorised by Sir Roderick Murchison and by a developing affiliation with the Royal Geographical Society. Livingstone had been developing repute in geography since his passage to Lake Ngami in 1849 despite having travelling without direct institutional backing. Indeed, the Royal Geographical Society's decision to award him a chronometer watch for the Ngami expedition (1849) and then to bestow the Patron's Medal (1854) for his subsequent travels helped to confirm Livingstone's position as one of Victorian Britain's foremost authorities on central African geography.

The Livingstone-Murray alliance then was one of mutual advantage. Murray was able to continue his monopoly on major works of travel and secure an author whose name would guarantee sales. On Livingstone's part, the association not only provided him with favourable financial terms, but with the prestige of the Murray firm whose reputation for publishing serious works of travel would help to ensure his book's place as an authorised work of expeditionary literature. Therefore, with the conditions of the publishing agreement in place and bolstered by the promise of assistance, Livingstone set out to draft Missionary Travels.

Composing New Copy Top ⤴

Beginning in January 1857, Livingstone took until August to draft his manuscript in full. He was still putting the finishing touches to it in mid-October of the same year, just a month before publication. However, despite this relatively short time-frame for a volume of almost 700 pages, the literary production of Missionary Travels was not straightforward.

In writing the book, Livingstone drew on the material recorded in his journals; his task was to refine these notes and shape them into narrative form. As his correspondence and diaries demonstrate, Livingstone was a capable writer but compiling a major travelogue was a task on a new scale, both labour intensive and time consuming. A significant challenge was to prepare the book quickly in order to meet the escalating public demand. As Henderson notes, the pressure to publish was compounded by rival publishers who brought out "unauthorised […] compilations of existing materials or personal letters" in order to capitalise on anticipation and beat Livingstone to his own task (2013:181; see Anon. 1857 for one such compilation).

To speed up the process of producing new matter, Livingstone experimented with alternative composition methods. Several months into writing he took on an assistant, Mr Logsdon, whose task was to transcribe as Livingstone composed his narrative verbally. The collaboration, arranged and paid for by Murray, did not prove a success. "I have made a fair attempt to get on in the way of dictating from my journal," Livingstone wrote to his publisher: "Mr Logsdon writes very nicely and I am satisfied with his abilities but I find that I cannot succeed the fault being entirely in myself" (LivingstoneAll citation references to "Livingstone" are to David Livingstone unless otherwise specified. 1857i).

![Notebook with Draft of Analysis of the Language of the Bechuanas and Other Miscellaneous Items (Livingstone 1850-52:[92]-[93]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, University of Glasgow Photographic Unit, and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). Notebook with Draft of Analysis of the Language of the Bechuanas and Other Miscellaneous Items (Livingstone 1850-52:[92]-[93]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, University of Glasgow Photographic Unit, and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/missionary-travels-manuscript/composing-publishing-missionary-travels-1/liv_000026_0092-0093-article-cropped-1200.jpg)

Notebook with Draft of Analysis of the Language of the Bechuanas and Other Miscellaneous Items (Livingstone 1850-52:[92]-[93]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, University of Glasgow Photographic Unit, and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. In composing Missionary Travels, Livingstone returned to the notebooks and journals that he had kept during his first period in southern Africa (1841-56). The pages from this notebook contain an early draft of Livingstone’s famous dialogue with the rainmaker. This dialogue later appeared (with revisions) in Missionary Travels (see Livingstone 1857aa:23-25).

Livingstone did not find dictation conducive to good writing. The difficulty was constructing coherent prose extemporaneously, without direct access to the page: "I feel quite unable to dictate continuously or give a connected narrative without seeing the preceding parts of the sentence" (Livingstone 1857i). When the use of an amanuensis failed to produce the desired results, Livingstone soon returned to the pen himself: "I shall go on as usual," he told Murray, "slow though that way is unless you think otherwise" (Livingstone 1857i).

Although his first use of a transcriber came to nothing, Livingstone did not give up the plan altogether. In fact, he set his brother Charles to the task several months later. Charles had emigrated to the United States in 1840, studying for the ministry in Oberlin College, Ohio, and Union Theological College, New York (Vetch 2008b). Arriving in London in April 1857 when on leave from his ministerial duties, he was soon enrolled into assisting with Missionary Travels (Livingstone 1857m).

The nature of Charles's script in the third volume of the manuscript indicates that one of his tasks was to take down passages dictated by Livingstone. Unlike the rest of the document, the lengthy section in Charles's hand is thus characterised by the use of shorthand for several recurring words. Livingstone's collaboration with his brother was more effective than the earlier one with Logsdon, for it evidently continued for quite some time. And Charles's assistance was formally supported by the publisher; as Livingstone noted, Charles earned £30 for his efforts which he requested to be "paid to his wife in America" (Livingstone 1857u).

The view onto campus from the entryway of the Mudd Center, Oberlin College Library, Oberlin, Ohio, 2017. Copyright Kate Simpson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. Charles Livingstone studied at Oberlin College in the 1840s. The college archives hold four volumes of a draft of Narrative of an Expedition to the Zambesi and its Tributaries. These volumes are written in Charles Livingstone’s hand and feature editorial corrections by David Livingstone, a composition format that resembles parts of the Missionary Travels manuscript.

Livingstone's marginalia across the three volumes show that his regular practice was to proof and supplement his own work in manuscript. This practice was necessarily more intensive where he had dictated passages to an amanuensis, as in the case of working with Charles. Livingstone clearly pored over his brother's work, sometimes making only minor corrections but at others writing multiple pages of additional material (see Livingstone 1857dd:[185]-[193]).

It was perhaps the resulting messiness that led Livingstone to take on a copyist, who would produce clean manuscript suitable for the publisher and printer's eye. Certainly, it seems unlikely that copying was standard practice across all three volumes. Had Livingstone used a copyist consistently, there might be something more than the small portion of copied text that survives today. The probable scenario is that copying only became necessary when the author began composing by dictation, especially given that the remaining evidence of the copyist's handiwork is a reproduction of a passage written by Charles and then heavily corrected by Livingstone (Livingstone 1857 dd:[252]-[272]).

The first mention of a copyist in the Missionary Travels correspondence appears on 17 June 1857, when Livingstone was some months into writing. When his next door neighbour (possibly Wilbraham Taylor) began performing the task, Livingstone commended the advantages of copying to his publisher. The "recopied" manuscripts, he told Murray, "contain more than when written by myself, and are probably more correct as I go over them after my amanuensis" (Livingstone 1857t). In other words, although he had already corrected and supplemented material transcribed by Charles, Livingstone was glad of the opportunity to make further refinements when reviewing the copyist's reproduction.

Portrait of the Rev. Charles Livingstone, Brother of the Explorer. From an original picture by Charles Gow, Esq. Illustration from James E. Ritchie, The Pictorial Edition of the Life and Discoveries of David Livingstone, 2 vols (London and Edinburgh: A Fullarton & Co., 1876-1879), 1:455. Copyright Adrian S. Wisnicki. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. Charles Livingstone assisted his brother’s work on Missionary Travels by acting as an amanuensis and critical editor. Later, Charles travelled to central Africa as a member of David Livingstone’s Zambezi Expedition and co-authored the resulting publication, Narrative of an Expedition to the Zambesi and its Tributaries (1865). That book – like Missionary Travels – was published by John Murray.

In producing new copy, Livingstone's methods were partly influenced by expediency. Having made slower progress in his writing than anticipated, he was prepared to experiment with dictation and transcription. Although his initial collaboration with Logsdon was unsuccessful, Livingstone was willing to make another attempt with his brother a little over a month later. His hope was that such support would "help me on a little quicker" (Livingstone 1857m).

But if Livingstone adapted his methods in order to accelerate his progress, he was clearly not prepared to compromise the quality of his work. His habit of correcting and supplementing material in his brother's hand and even the work of the copyist reveals a disposition towards revision; Livingstone did not allow the pressure to produce new material to prevent him from devoting careful editorial attention to the narrative he was writing.

Livingstone's varying methods of drafting new matter, however, were not the only complications involved in the composition of Missionary Travels. There were other complexities in the book's production that are not immediately obvious and which require careful elaboration.

Circulating Manuscript and Print Top ⤴

The fact that the Missionary Travels manuscript survives today in three bound volumes (Livingstone 1857bb, 1857cc, 1857dd) can create a misleading impression of its composition. Unlike current publishing practice, Livingstone did not write a full manuscript before sending it to the publisher for comments and copy-editing and eventually receiving a full set of proofs.

Rather, in Livingstone's case, practices that are today discrete phases of publication actually occurred simultaneously. Although Livingstone was still producing manuscript in August 1857 and did not complete his preface until a few weeks prior to publication, the editorial revision process began to happen earlier (Livingstone 1857w, 1857x). In fact, in April 1857, only three months into writing, he was already receiving printed material for emendation.

This much emerges in a letter to Murray dated 6 April. At this point, Livingstone had just secured Thomas Binney, a Congregationalist minister and founder of the Colonial Missionary Society (Jones 2004), to aid him in the task of revision. Still ironing out the process of working with a literary aid, Livingstone requested that any "sheets" for correction would first be returned to him before they were sent to Binney for review (Livingstone 1857k).

| Letter to John Murray III (Livingstone 1857k:[1]-[2]). Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. Livingstone wrote over forty letters to Murray in 1857 about the composition and publication of Missionary Travels. In the above sample, Livingstone acknowledges the assistance he is receiving from the Rev. Dr. Thomas Binney in revising the galley proofs of the forthcoming book. |

The material that was being returned to Livingstone at this stage was definitely in type because it was sent from one of the publisher's regular printers, William Clowes. Moreover, Livingstone passed on Binney's favourable impression of the typeface to Murray and confessed his own surprise that the press intended to reset the book in due course after revisions. Livingstone knew that this was no cheap process and asked Murray – almost in disbelief – if the print would really be "recomposed" (Livingstone 1857k).

The "sheets" being sent to Livingstone – which he also calls "slips" – were presumably galley proofs that were never intended to serve as final text but instead were prepared for copyediting and revision purposes. Given that setting type was a lengthy and expensive undertaking, it may seem surprising that the publisher went to such trouble. But in the nineteenth century, it was not uncommon for authors to have multiple opportunities for revision and correction during the production process. Depending on sales expectations and the prestige of the author, Victorian publishers were sometimes prepared to offer several proofs and so permit several additional stages of editing (Dooley 1992).

Not all of Murray's authors got to see galley proofs so quickly, especially while still in the process of composing the first draft. On the submission of manuscripts, authors could face considerable delays before their book progressed to the next phase (Keighren, Withers, and Bell 2015:186). In Livingstone's case, the pressure to publish quickly and capitalise on public expectation probably accounts for the overlap in the production of manuscript and proofs; the method adopted by the publisher is evidence of an effort to expedite publication. Although Missionary Travels took longer to complete than Livingstone had hoped, the eleven-month time frame – between beginning work and seeing the book on the shelf – was shorter than many authors could expect.

![Galley proof from Missionary Travels (Livingstone 1857dd:[1]). Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/). Galley proof from Missionary Travels (Livingstone 1857dd:[1]). Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/missionary-travels-manuscript/composing-publishing-missionary-travels-1/liv_000101_0001-article-1200.jpg)

Galley proof from Missionary Travels (Livingstone 1857dd:[1]). Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. This printed "slip," as Livingstone calls it, shows some minor editorial markup and a long arrow indicating where additional manuscript material should be inserted. Several additional pages of galley proofs survive in the Livingstone Museum, Zambia.

Very little of the Missionary Travels galley proofs appears to have survived. The present edition includes a small portion of only one "slip," number 68 (Livingstone 1857dd:[1]), which was found tucked inside the third volume of the manuscript (Livingstone 1857dd). Nonetheless, the fragment demonstrates that Livingstone was making considerable changes at this stage, since it is accompanied by two handwritten folios marked with the instruction, "To be inserted at bottom of small slip 68*" (1857dd:[2]-[3]). The alterations introduced in galley proofs were thus far from minor: at the first phase of print, the text was not fixed but remained highly fluid.

From the correspondence, it appears that Livingstone tended to examine the galley proofs more than once. It seems that he consulted them himself first, making his own round of corrections before sending them to others for advice. As Livingstone put it to Murray, he wanted to review the proofs before Binney did in order to clarify the prose and forestall potential confusion: "I find that Mr Binney is often puzzled much by what my correction makes quite clear. It will save him much trouble" (Livingstone 1857k).

In working on the proofs, Livingstone solicited advice from a number of readers. In addition to Binney and Murray himself, others consulted included the eminent naturalist Joseph Hooker, who offered "to examine anything botanical" (Livingstone 1857y, 1857z), and the experienced traveller Major Frank Vardon, who also evaluated some of the illustrations (Livingstone 1857f; also see Livingstone 1857l, 1857o). Moreover, Charles, Livingstone's brother, was not only Livingstone's amanuensis but his critical reader. Writing to Murray in May 1857, Livingstone promised that he would forward some corrected slips "as soon as my brother has read them" (1857n).

| (Left; top in mobile) Captain Frank Vardon. Illustration from W. Edward Oswell, William Cotton Oswell: Hunter and Explorer, 2 vols (London: William Heinemann, 1900), 2:134. Courtesy of the Internet Archive. (Right; bottom) J. D. Hooker. From the Portrait by George Richmond (1855). Illustration from Leonard Huxley, Life and Letters of Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker O.M., G.C.S.I., 2 vols (London: John Murray, 1918), 1:frontispiece. Courtesy of the Internet Archive. Vardon and Hooker were two of the associates whose expertise Livingstone sought while working on Missionary Travels. Vardon had become acquainted with Livingstone during a southern African hunting trip to Mabotsa in 1846. Hooker corresponded with Livingstone from 1857 onward and later assisted in planning the Zambezi Expedition by providing a set of instructions and objectives for the expedition’s Economic Botanist. |

Following comments from his readers, Livingstone would then review the galley proofs once again to make alterations in response to suggestions. For instance, he decided to incorporate information on his religious conversion at Binney's encouragement and promised Murray that he would "embody" the publisher's own comments in revision at the same time (Livingstone 1857m). Revising the galley proofs in this fashion was probably consistent practice; in another letter, Livingstone told his publisher that he was at work on the slips "incorporating the corrections" in an effort to "make all plain" (1857n).

There was thus a simultaneity of composition and revision in the production of Missionary Travels. Livingstone was at work in revising and supplementing galley proofs, while receiving comments from others, while also writing entirely new matter. The process was further complicated, moreover, by the handling of manuscript material itself; the folios didn't pass seamlessly from Livingstone straight to galley proofs.

Rather, manuscript pages were first distributed to an anonymous reader: Murray's "red ink man." Following the anonymous reader's scrutiny, Livingstone often had the pages returned to him so that he could peruse the suggestions and make the requisite alterations. On 6 April, for instance, in a letter that also discussed galley proofs, Livingstone asked Murray to post him "some of the red ink man's work" so that he could "correct in manuscript" (Livingstone 1857k). Folios were thus being sent back and forth between author and publisher for initial correction and for Livingstone's subsequent approval or emendation.

![Image of a page segment from the Missionary Travels manuscript (Livingstone 1857dd:[4]), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/). Image of a page segment from the Missionary Travels manuscript (Livingstone 1857dd:[4]), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/missionary-travels-manuscript/composing-publishing-missionary-travels-1/liv_000101_0004-article-crop-1200.jpg)

Image of a page segment from the Missionary Travels manuscript (Livingstone 1857dd:[4]), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. This segment shows that the Missionary Travels galley proofs were not printed in a single step; rather, individual sections were set in type throughout the composition process, as and when they were ready. The pencil annotation at margin left, written in the hand of an unknown editor, provides an instruction for the current manuscript section (XXXVI) to be printed as galley proofs: "Set up in slips – but in the type of the Book."

This is also highlighted in an exchange of manuscripts towards the end of March 1857. On 24 March, Livingstone posted Murray his recent work on sections XVIII to XXII, but then less than a week later sent him an earlier portion of manuscript, sections I to XIII. From this chronology, we can gather that Livingstone had been revising the preceding sections or, as he put it, trying to "sweeten" them (1857h, 1857j). While Livingstone was at work on new text, earlier parts of manuscript copy were evidently being marked up by the editor and then returned to the author for further revision.

The composition of Missionary Travels and its journey through the press was thus remarkably non-linear. The galley proofs, which are conventionally associated with the later phases of literary production, began to be distributed and revised early in the process even while the composition of new material and revision in manuscript was ongoing. Undoubtedly, this made a demanding task for the author. With readers and editors quickly becoming involved at both levels – manuscript and proofs – Livingstone was required to work on discrete portions of the book concurrently.

But if there were inherent challenges to this system of production, it was also one that provided Livingstone with assistance. The production of travelogues in the nineteenth century was intensely collaborative and, in Livingstone's case, the circulation and exchange of manuscript and proofs opened the way for multiple individuals to have input in shaping the text as it made passage to print. Yet, with several levels of correction and with comments coming from a range of readers, Livingstone would find that he needed to make considerable effort in order to retain control of his text.

![John Murray III and Anon., David Livingstone - Boat Scene (Painted Magic Lantern Slide), [1857], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND. John Murray III and Anon., David Livingstone - Boat Scene (Painted Magic Lantern Slide), [1857], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND.](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_014067_0001-carousel.jpg)

![Image of two pages from Livingstone's Field Diary XVI (Livingstone 1872h:[2]-[3]). CC BY-NC 3.0 Image of two pages from Livingstone's Field Diary XVI (Livingstone 1872h:[2]-[3]). CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000016_0003-carousel.jpg)

![David Livingstone, Map of Lakes Nyassa and Shirwa [1864?], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND; Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson, CC BY-NC 3.0 David Livingstone, Map of Lakes Nyassa and Shirwa [1864?], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND; Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson, CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000077_0001-tile.jpg)

![Letter to John Murray III (Livingstone 1857k:[1]). Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/). Letter to John Murray III (Livingstone 1857k:[1]). Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/missionary-travels-manuscript/composing-publishing-missionary-travels-1/liv_000990_0001-article-crop-1200.jpg)

![Letter to John Murray III (Livingstone 1857k:[2]). Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/). Letter to John Murray III (Livingstone 1857k:[2]). Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson (as relevant). Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/missionary-travels-manuscript/composing-publishing-missionary-travels-1/liv_000990_0002-article-crop-1200.jpg)