Field Diary XIV: An Overview

Cite page (MLA): Ward, Megan, and Adrian S. Wisnicki. "Field Diary XIV: An Overview." In Livingstone's Final Manuscripts (1865-1873). Megan Ward and Adrian S. Wisnicki, dirs. Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. University of Maryland Libraries, 2018. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/ad330d80-44ba-4144-aba3-cd890830b080.

This page introduces Field Diary XIV, which is part of our critical edition of Livingstone's final manuscripts (1865-73). The essay summarizes Livingstone's account of his iconic meeting with Henry Morton Stanley and documents their time together. The essay also analyzes Livingstone's renewed communication with Europe and the United States in the wake of this visit, as well as his account of ongoing local violence between African chiefs and the impact on this violence by Arab traders. The essay concludes with a description of the material features of the diary.

[View the critical edition or download a basic reading copy of Field Diary XIV.]

Field Diary XIV starts in late 1871 in Ujiji, where Livingstone has returned after failing to sail down the Lualaba River in central Congo and having witnessed a significant massacre led by slave traders in the village of Nyangwe. Starting from Ujiji, Livingstone circumnavigates Lake Tanganyika, determines that the Rusizi River flows into the lake (and so proves that the lake from its northern end cannot be a direct feeder of the Nile), returns to Ujiji, then travels east to Unyanyembe, where he rests for several months before leaving at the end of the summer to travel west yet again to the regions south of the lake.

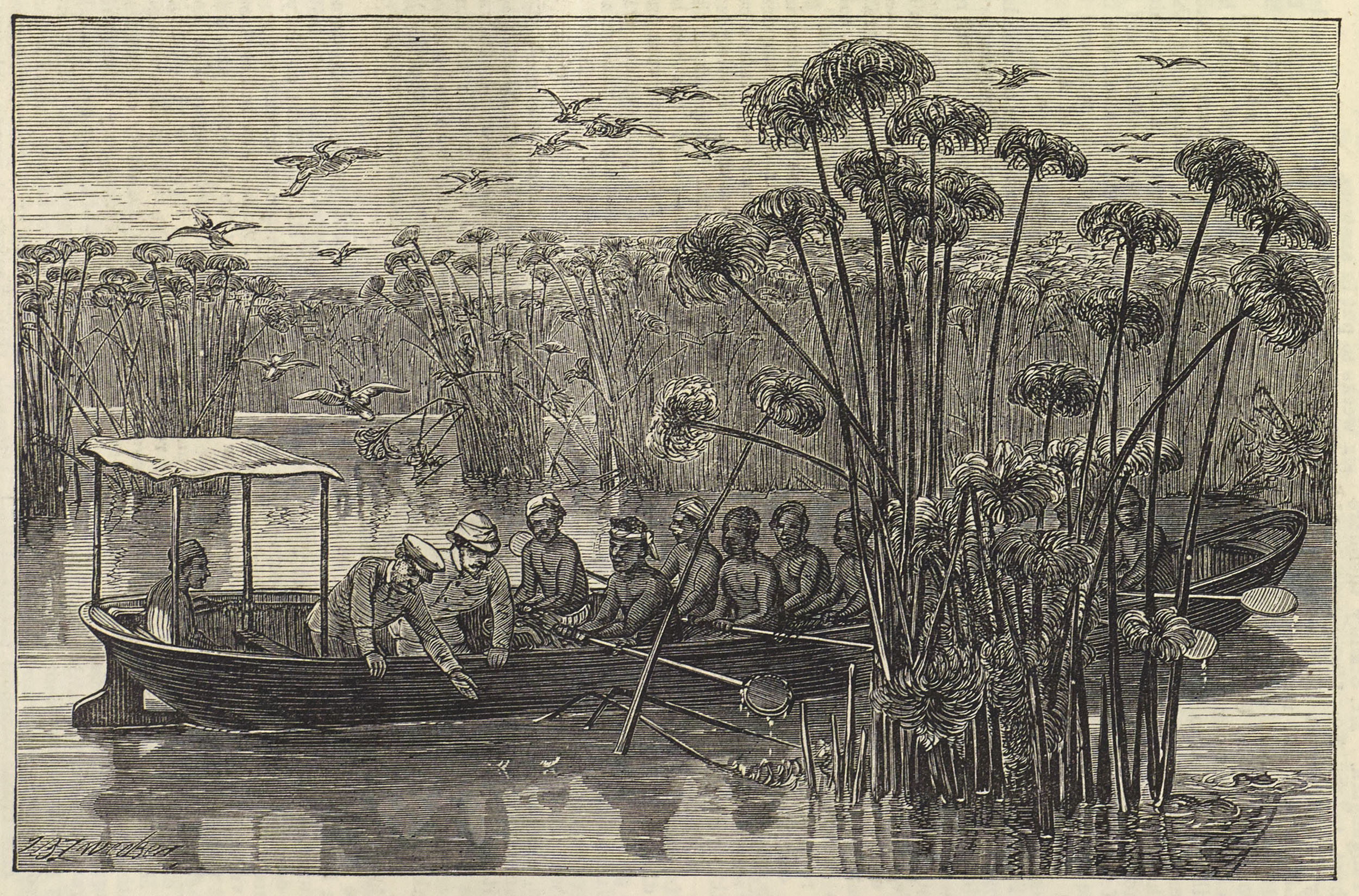

At the Mouth of the Rusizi, Lake Tanganyika. Illustration from Review of Henry M. Stanley's How I Found Livingstone (Anon. 1872:485), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. Stanley, who is pictured here alongside Livingstone, was the only European whom Livingstone encountered during the seven years of his final travels.

The most notable development in Field Diary XIV – when compared to previous diaries – is the presence of Henry Morton Stanley, author of the famous (and possibly apocryphal) phrase, "Dr. Livingstone, I presume?" Stanley had been dispatched by The New York Herald to central Africa to "find" Livingstone whose letters had not reached the outside world for many months. Livngstone and Stanley's meeting occurred before the beginning of this diary (the exact date is in dispute), and Livingstone first records Stanley's presence simply by noting "Mr Stanley severe fever" (1871n:[10]).

When Stanley, Livingstone, and their porters reach Unyanyembe on 18 February 1872, they find a cache of supplies waiting for them, including boxes that Stanley left before venturing west to find Livingstone, as well as a box that Livingstone himself left when he began his last journey. This box contains the 800-page record known as the Unyanyembe Journal. Stanley has brought supplies such as copper wire, medicine, tools, and a tent for Livingstone, as well as letters and newspapers. Livingstone is also pleased to find the box he had left four years earlier; his guns, bullets, china are intact and - though the box had been waiting for four years - he can still note with relief, "cheese good" (Livingstone 1871n:[44]).

| Images of two pages of Field Diary XIV (Livingstone 1871n:[32], [47]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. On the page at left (top in mobile), Livingstone has included a drawing of Bombay, perhaps the most famous of the many Africans who accompanied Europeans on expeditions in nineteenth-century Africa. On the page at right (bottom), Livingstone describes his parting from Stanley, marked with two red horizontal lines. |

On 14 March 1872, Stanley leaves Unyanyembe for the coast, and Livingstone sends with him the Unyanyembe Journal, "sealed with 5 seals American gold coin - anna & ½ & cake of paint with royal arms - Positively not to be opened" (Livingstone 1871n:[47]). Five days later and suffering from the loneliness of saying good-bye to Stanley, Livingstone recommits himself to his quest: "My Jesus, my King, my life, my all = I again dedicate my whole self to thee = accept me and grant O Gracious Father that ere this year is gone I may finish my task" (Livingstone 1871n:[48]).

As a result of his contact with Stanley, Livingstone engages in a new level of communication with Europe and America. While in Unyanyembe, Livingstone receives rolls of letters, newspapers, as well as books written by explorers Samuel Baker and Edward Young. More than in previous diaries, then, we see Livingstone pondering and responding to western political and scientific communities alongside his ongoing observations about local politics, geography, and environment. For instance, Livingstone writes a two-column article for The New York Herald tries to "enlist American Zeal to stop East Coast slave trade" (Livingstone 1871n:[60]-[61]). He even responds in his diary to a bit of court gossip.

| Images of two pages of Field Diary XIV (Livingstone 1871n:[120], [129]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. Illustrations of (top) a member of the Baganda ethnic group and (bottom) a trout from Lake Tanganyika. Livingstone's depiction of the former reflects a common practice of nineteenth-century travel narratives, which presented supposedly representative individuals of a particular ethnic group from multiple angles and in the context of various cultural artefacts. |

At the same time, however, Livingstone continues to record local politics, particularly a war that "rages between [chiefs] Mukamba and Warmashanya or Uarmasane" (Livingstone 1871n:[9]). This war continues for the span of the diary, almost a year, involves the Arabs, as well, and causes widespread hunger in the region. Many times Livingstone records the exchange of peace offerings and suggests the war will end soon, but accurate news is difficult to acquire. For example, Livingstone first records that his friend Ghamees Wodin Lagh was killed in the conflict but then - later that same day - concludes that he was not: "Report contradicted afterwards" (Livingstone 1871n:[63]).

As in previous diaries, Livingstone writes from both ends of the diary at once, though this present diary differs from previous ones in that the section written upside-down from the end does not seem to serve a distinct purpose (in previous diaries the back section usually records random notes). Perhaps due to illness, Livingstone makes fewer long entries in this diary than in others, and lists and calculations are scattered throughout rather than concentrated in the back section. Livingstone sometimes only notes the date with no information, or only records basic meteorological and geographical information with no narrative.

![An image of two pages of Field Diary XIV (Livingstone 1871n:[98]-[99]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of two pages of Field Diary XIV (Livingstone 1871n:[98]-[99]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/field-diary-xiv-overview/liv_000014_0098-0099-article.jpg)

An image of two pages of Field Diary XIV (Livingstone 1871n:[98]-[99]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. In this elaborate, two-page illustration, Livingstone offers a comparative depiction of the residential quarters of (left) Arabs and (right) the Baganda ethnic group.

There is also less overlap between the front and back sections of the diary. The back section, for instance, contains quite a few substantial passages observing an African bird, the whydah. Livingstone observes the whydah from April 1872 through to the end of the summer, recording its nesting, mating, and baby-rearing practices, but does not mention the whydah at all in the front section of the diary.

Field Diary XIV is one of Livingstone's many brown, flip-top Lett's notebooks, written almost exclusively in pencil: primarily in grey, secondarily in blue, with some later additions in red. It measures 140 mm high by 89 mm wide by 14 mm thick and includes a newspaper clipping. The tile of the clipping is "Further from Dr. Livingstone" and is dated "London, Aug. 29" without a year. The clipping contains only one paragraph, and notes that Dr. Kirk writes that Livingstone is still alive in Africa and still committed to finding the source of the Nile. Even as Livingstone became more public in his work against the Arab slave trade, this article records that "the Arabs there count him as a resident" and "in the region no feeling is manifested toward him" (Livingstone 1871n:[131]).

![An image of a page of Field Diary XIV (Livingstone 1871n:[131]), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of Field Diary XIV (Livingstone 1871n:[131]), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/field-diary-xiv-overview/liv_000014_0131-article.jpg)

An image of a page of Field Diary XIV (Livingstone 1871n:[131]), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. This image shows a clipping related to Livingstone that has been pasted into the field diary. It is not clear if Livingstone added this clipping or someone after him. If Livingstone, the clipping most likely came from Stanley and so offers a possible example of the sort of oral information on which the latter would have relied when searching for the former.

![John Murray III and Anon., David Livingstone - Boat Scene (Painted Magic Lantern Slide), [1857], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND. John Murray III and Anon., David Livingstone - Boat Scene (Painted Magic Lantern Slide), [1857], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND.](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_014067_0001-carousel.jpg)

![Image of two pages from Livingstone's Field Diary XVI (Livingstone 1872h:[2]-[3]). CC BY-NC 3.0 Image of two pages from Livingstone's Field Diary XVI (Livingstone 1872h:[2]-[3]). CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000016_0003-carousel.jpg)

![David Livingstone, Map of Lakes Nyassa and Shirwa [1864?], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND; Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson, CC BY-NC 3.0 David Livingstone, Map of Lakes Nyassa and Shirwa [1864?], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND; Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson, CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000077_0001-tile.jpg)

![An image of a page of Field Diary XIV (Livingstone 1871n:[32]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of Field Diary XIV (Livingstone 1871n:[32]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/field-diary-xiv-overview/liv_000014_0032-article.jpg)

![An image of a page of Field Diary XIV (Livingstone 1871n:[47]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of Field Diary XIV (Livingstone 1871n:[47]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/field-diary-xiv-overview/liv_000014_0047-article.jpg)

![An image of a page of Field Diary XIV (Livingstone 1871n:[120]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of Field Diary XIV (Livingstone 1871n:[120]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/field-diary-xiv-overview/liv_000014_0120-article.jpg)

![An image of a page of Field Diary XIV (Livingstone 1871n:[129]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of Field Diary XIV (Livingstone 1871n:[129]). Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/in-his-own-words/field-diary-xiv-overview/liv_000014_0129-article.jpg)