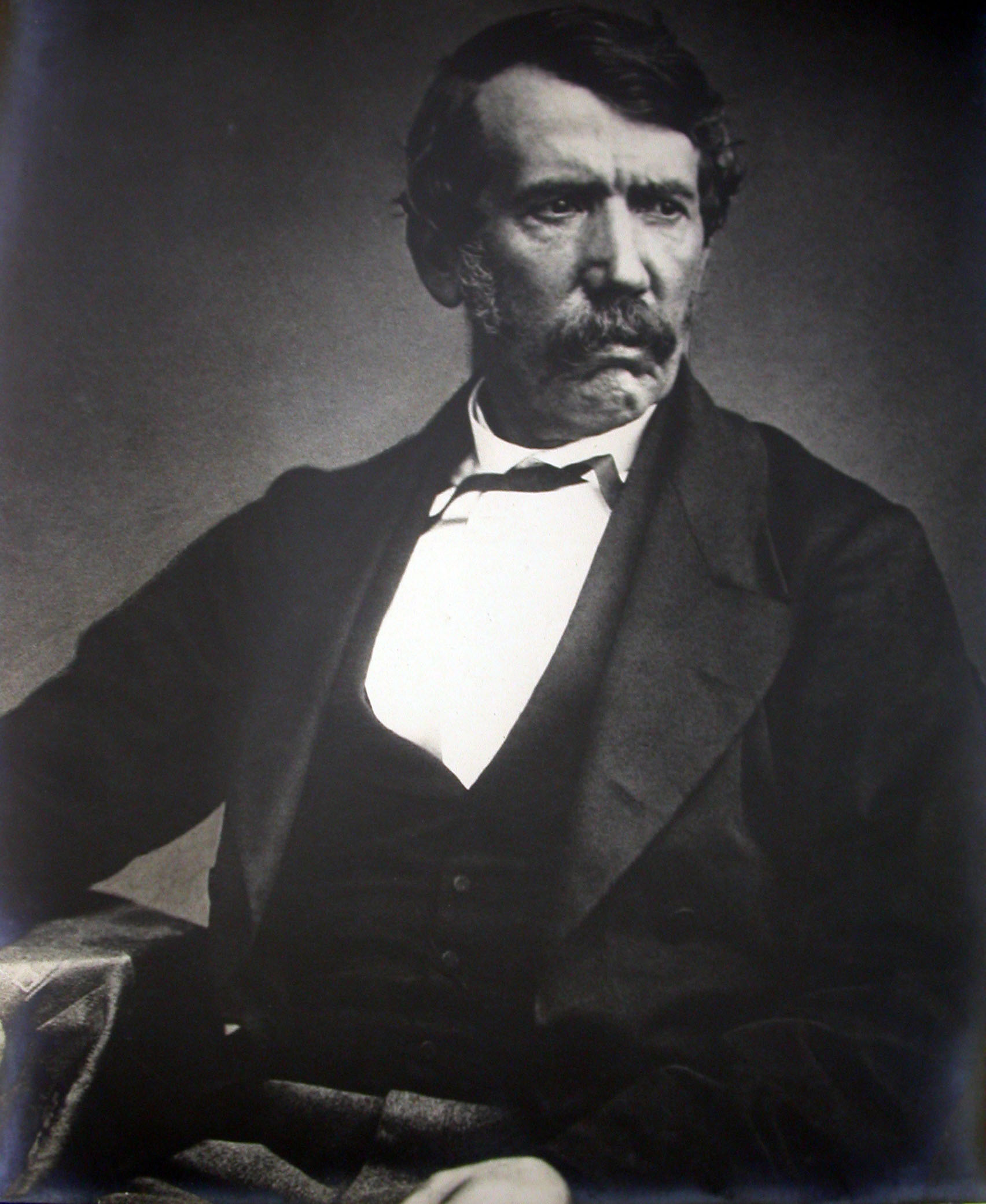

Livingstone in 1871

Cite page (MLA): Wisnicki, Adrian S. "Livingstone in 1871." Debbie Harrison, ed. In Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. Adrian S. Wisnicki, dir. Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. University of Maryland Libraries, 2017. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/ee070bc7-7f68-4e61-962d-038e1703231a.

This section offers an overview of Livingstone’s final travels and objectives, including the historical circumstances in which he composed the 1871 Field Diary. The section also presents a short history of the village of Nyangwe, describes the main part of Livingstone's sojourn in the village, and sets out the key circumstances surrounding the massacre that Livingstone witnessed in Nyangwe on 15 July 1871. Finally, the section examines some of the most important differences in the representations of the massacre in the 1871 Field Diary, the Unyanyembe Journal (1866-72), and Livingstone's Last Journals (1874).

Livingstone in 1871 Top ⤴

David Livingstone wrote the 1871 Field Diary during his final African expedition (1866-73). Sir Roderick Murchison, President of the Royal Geographical Society, set Livingstone’s primary objective for this expedition as determining the water system of central Africa by exploring the region between Lakes Nyassa and Tanganyika. Murchison hoped that by this expedition Livingstone would "be paving the way for the introduction of social improvements among the natives, by the promotion of fair barter and commerce, to the exclusion of the trade in slaves" and that Livingstone would "act as a pioneer in removing those obstacles" that prevented Christian missionaries from traveling to these regions (Murchison 1864-65:264).

With these statements, Murchison reiterated Livingstone’s own vision for linking exploration with Christianity, commerce, and civilization in the service of ending the slave trade in Africa. Though Livingstone’s final journey pre-dated the European scramble for Africa of the 1880s, Murchison’s words gave evidence of the mounting desire for British influence on the continent. Framed as improving life for Africans, Livingstone’s mission – if successful – would increase British production and trade and increase the widening sphere of British control.

Photograph of David Livingstone, 1865. Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Object images used by permission. May not be reproduced without the express written consent of the National Trust for Scotland, on behalf of the Scottish National Memorial to David Livingstone Trust.

Livingstone had unveiled this vision in his best-selling Missionary Travels and Researches (1857), a book that made him a household name by detailing his four-year coast-to-coast journey across Africa. Livingstone’s first attempt to realize the vision, the ill-fated Zambezi Expedition (1858-64), ended in failure and recall, due to problems caused by natural obstacles and personal conflicts among expedition members. The 1866 expedition offered Livingstone a chance to redeem his reputation by paving the way for a potential new era of British colonial endeavor in Africa.

The expedition would also tackle – Murchison hinted – the thorny and highly controversial issue of the Nile River’s ultimate source (Murchison 1864-65:264-65; for more on the objectives of Livingstone's final expedition, see Bridges 1973). In the 1860s, the location of this source divided British geographers and explorers. Some believed that the Nile originated (as it does) in Lake Victoria, which the explorer John Hanning Speke had first sighted in 1858. Others argued that a river flowing out of the northern end of Lake Tanganyika gave rise to the Nile (this river, the Rusizi, in fact flows into the lake and has no connection to the Nile). But no one knew for certain. "Nothing short of actual exploration can determine these questions," stated Murchison (1864-65:265).

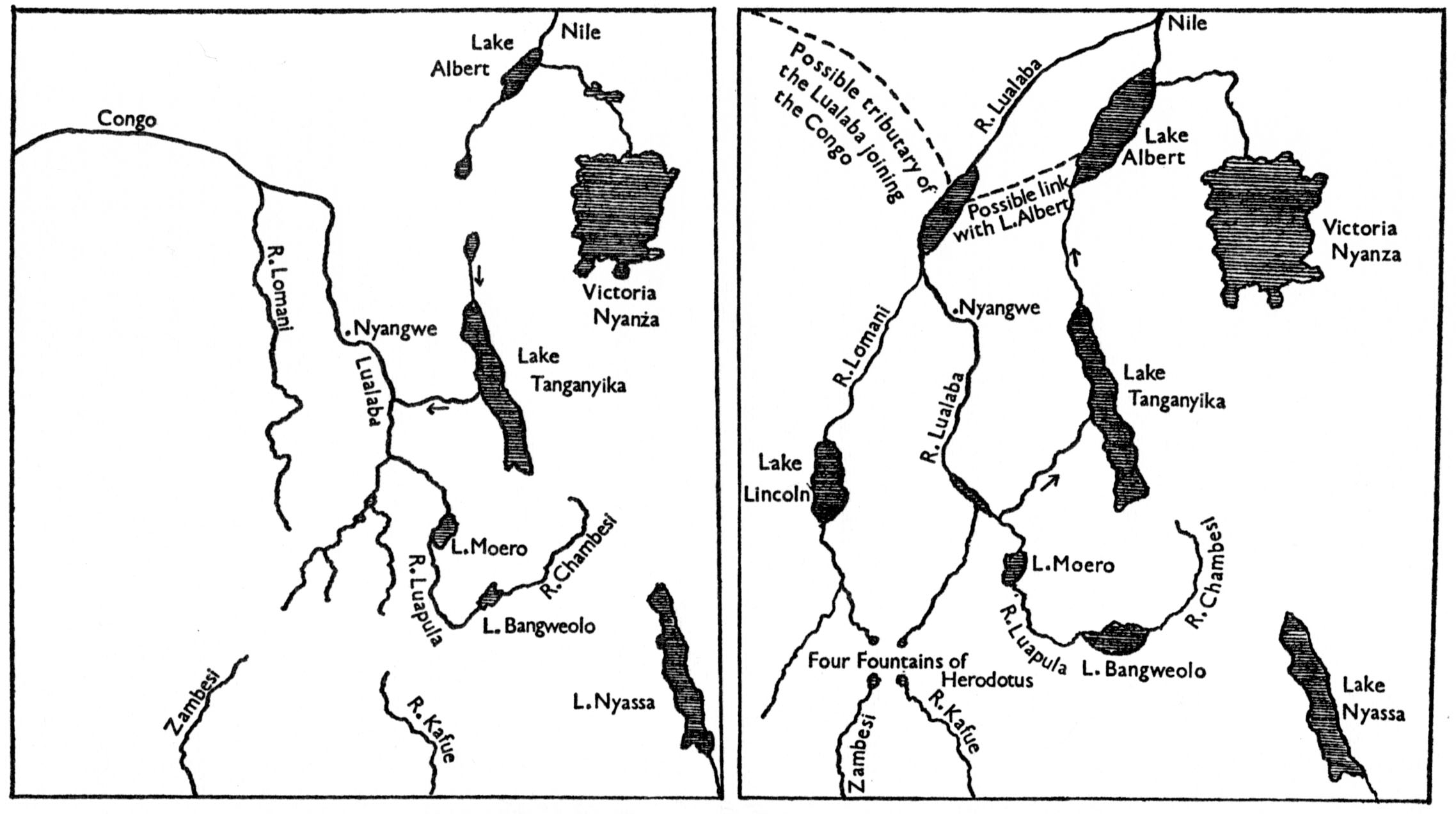

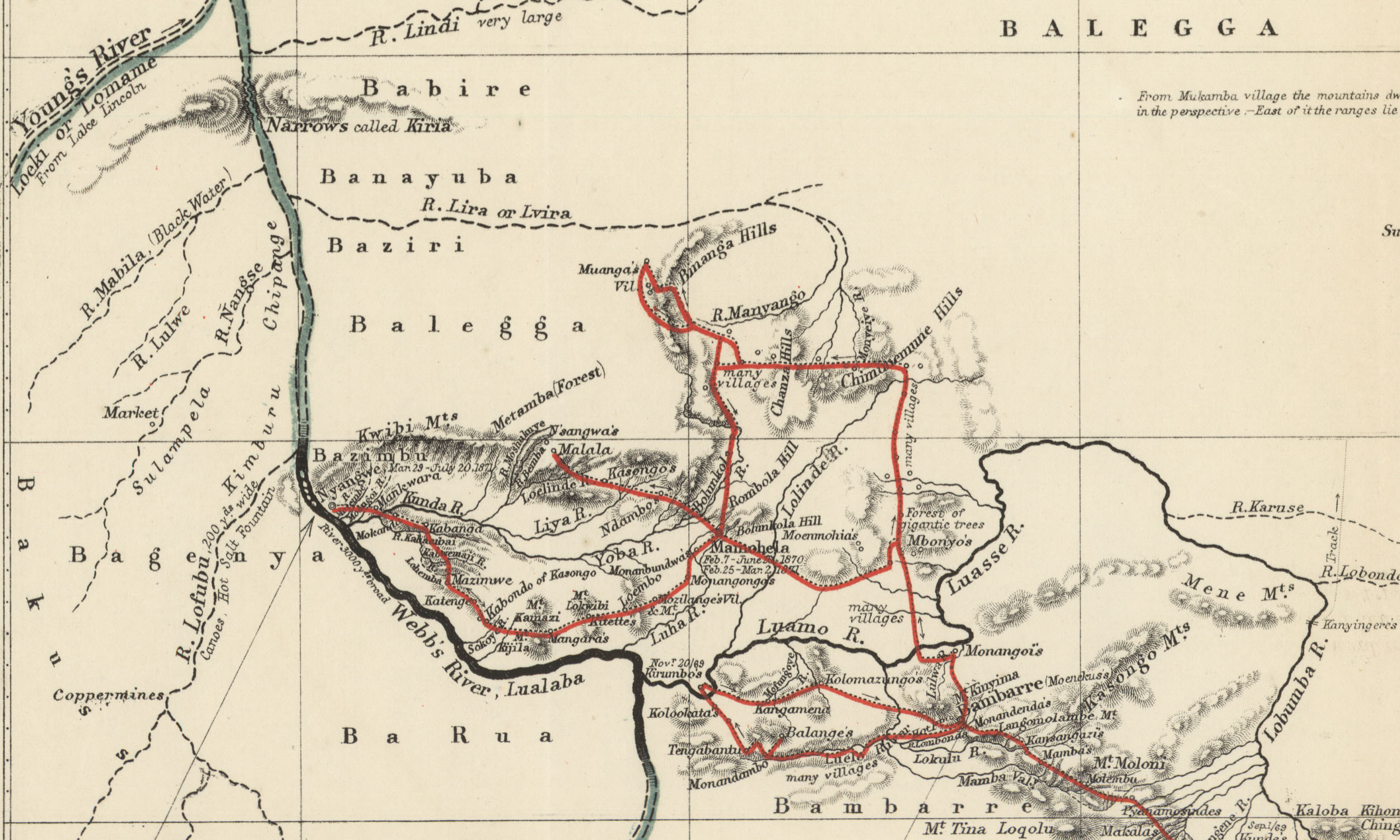

Livingstone’s final expedition took him over a wide stretch of east and central Africa, through the areas that today constitute Tanzania, Mozambique, Malawi, Zambia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Livingstone – as he travelled and as he questioned other travellers – developed an elaborate theory of the central African river system. He "came to the conclusion that there were three main interconnecting 'lines of drainage' in central Africa," all running north to south in parallel (Jeal 1973:323). All three lines, according to Livingstone, fed the Nile.

The central African watershed as it is (left) and as Livingstone believed it to be (right). Illustration from Tim Jeal's Livingstone (1973:324). Published by permission of Tim Jeal.

In Livingstone's theory, the eastern line (which ran through Lakes Tanganyika and Albert) and the central line (the Congo’s Lualaba River) both took rise – at least partly – in Lakes Moero and Bangweulu farther to the south. The central line and western line (the Congo’s Lomami River), however, originated in a more exotic source. In one of his letters, Livingstone described it as "a remarkable mound" that "gives out four fountains not more than 10 miles apart," with the two fountains to the south giving rise to "the Liamba or Upper Zambesi" and "the Kafui" rivers. These four fountains, Livingstone concluded, were "probably the Nile fountains, which were described to Herodotus as unfathomable, and sending one-half of the water to Egypt, the other half to inner Ethiopia" (Livingstone 1879:480; cf. Herodotus 1987:141-45).

During the final years of his life, Livingstone became obsessed with reaching this mound and proving his theory of the river system. In 1869, Livingstone’s explorations took him from Ujiji, an Arab trading depot on the eastern shore of Lake Tanganyika, to the Manyema region west of the lake, which Zanzibari Arab traders had just begun to pioneer in their search for ivory. Livingstone intended to pass through Manyema rapidly, then strike the Lualaba River, which lay some 240 miles west of Ujiji (Livingstone estimated the distance at 300 miles), with the goal of exploring the river and resolving its mysteries. Did it feed the Nile (as Livingstone hoped) or was it part of the Congo River system (as Livingstone feared)?

| I could not for a long time be sure that it was not the Congo – & who would run the risk of being put into a cannibal Manyema pot and be converted into black man for anything less than the grand old Nile. |

| David Livingstone, Letter to William R.S.V. Fitzgerald, 13 March 1872 |

The journey to the Lualaba, however, took much longer than anticipated. Livingstone departed from Ujiji on 12 July 1869. He did not reach Nyangwe, a small village on the right bank of the Lualaba, until nearly two years later, 30 March 1871. The delay in travel had partly to do with the "large belts of primeval forest" that lay between Tanganyika and the Lualaba, and partly because "irritable ulcers on the feet" and other issues had stopped Livingstone in the Congolese village of Bambarre for nearly seven months from 22 July 1870 to 16 February 1871 (Livingstone 1872a:2; 1870e:X).

Due to these delays, Livingstone – now some 880 miles from the east coast of Africa – had run low on many essential supplies, including writing paper and iron gall ink. He did have a single eight-page copy of The Standard newspaper dated 24 November 1869, which he had received on 4 February 1871 along with letters and other materials from Horace Waller, his friend and future editor (see the section on The Manuscript of the 1871 Field Diary). Livingstone cut up the sheets of this newspaper and assembled two thirty-two page "copy-books" (Waller, in Livingstone 1874,2:114n.). Livingstone wrote his first entry in the first of these copy-books – now collectively known as the 1871 Field Diary – on 23 March 1871, just a few days before he reached the village of Nyangwe.

The Village of Nyangwe Top ⤴

The nineteenth century witnessed the consolidation of an Arab-African trading network across east Africa, and the gradual expansion of this network into the Congo in the search of new ivory fields. "[…]There were not only places where goods were stored and people gathered, such as ports and a few large markets," writes Catherine Coquery-Vidrovitch (2005:210), "but many smaller centers that we still know little about. The smaller centers may have moved from place to place and served as caravan stops, portage resting points, military posts, and slave markets on a more or less temporary basis. Together they made up a complete, structured trade network." Nyangwe played a key role in this network.

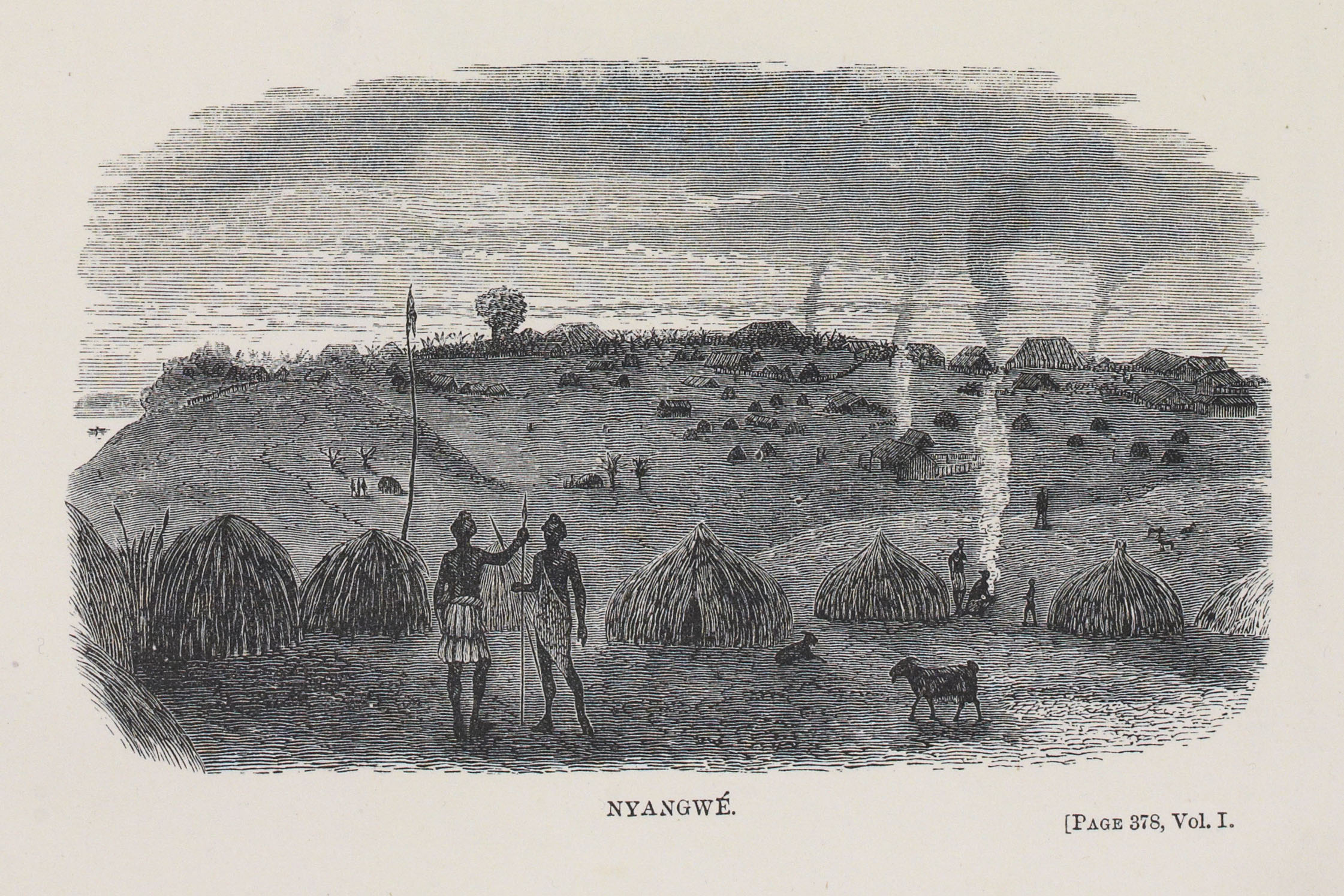

Nyangwe. Illustration from Cameron's Across Africa (1877a,1:opposite 378). Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland

In 1871 Nyangwe had only been an Arab trading depot for about ten years, but it was the westernmost Arab settlement in central Africa and, along with Ujiji and Tabora, one of the three main Arab centers on the trading routes that ran from the east coast of Africa into the interior. Although environmental conditions made travel to Nyangwe difficult, the fragmentation of the local populations facilitated the arrival of heavily-armed Arab caravans (Ceulemans 1959:43). In settling at Nyangwe, Arab traders and their African forces first depopulated the neighboring villages (Stanley 1876-77:25 Oct. 1876), then attacked and displaced Nyangwe’s original inhabitants, the Wagenya (or, as Livingstone calls them, the Bagenya) to the opposite bank of the Lualaba River (Cameron 1874:4 Aug. 1874). Finally, the Arabs maintained control over the settlement through the use of intimidation and violence.

Because of such violence, the Wagenya grew to distrust all new visitors to the region: "One hoary-headed old fellow said that no good to the Wagenya had ever resulted from the advent of strangers," wrote the explorer Verney Lovett Cameron, who visited Nyangwe a few years after Livingstone, "and he should advise each and all of his countrymen to refuse to sell or hire a single canoe to the white man" (1877a,2:6). Livingstone soon discovered that he would not be an exception to this distrust.

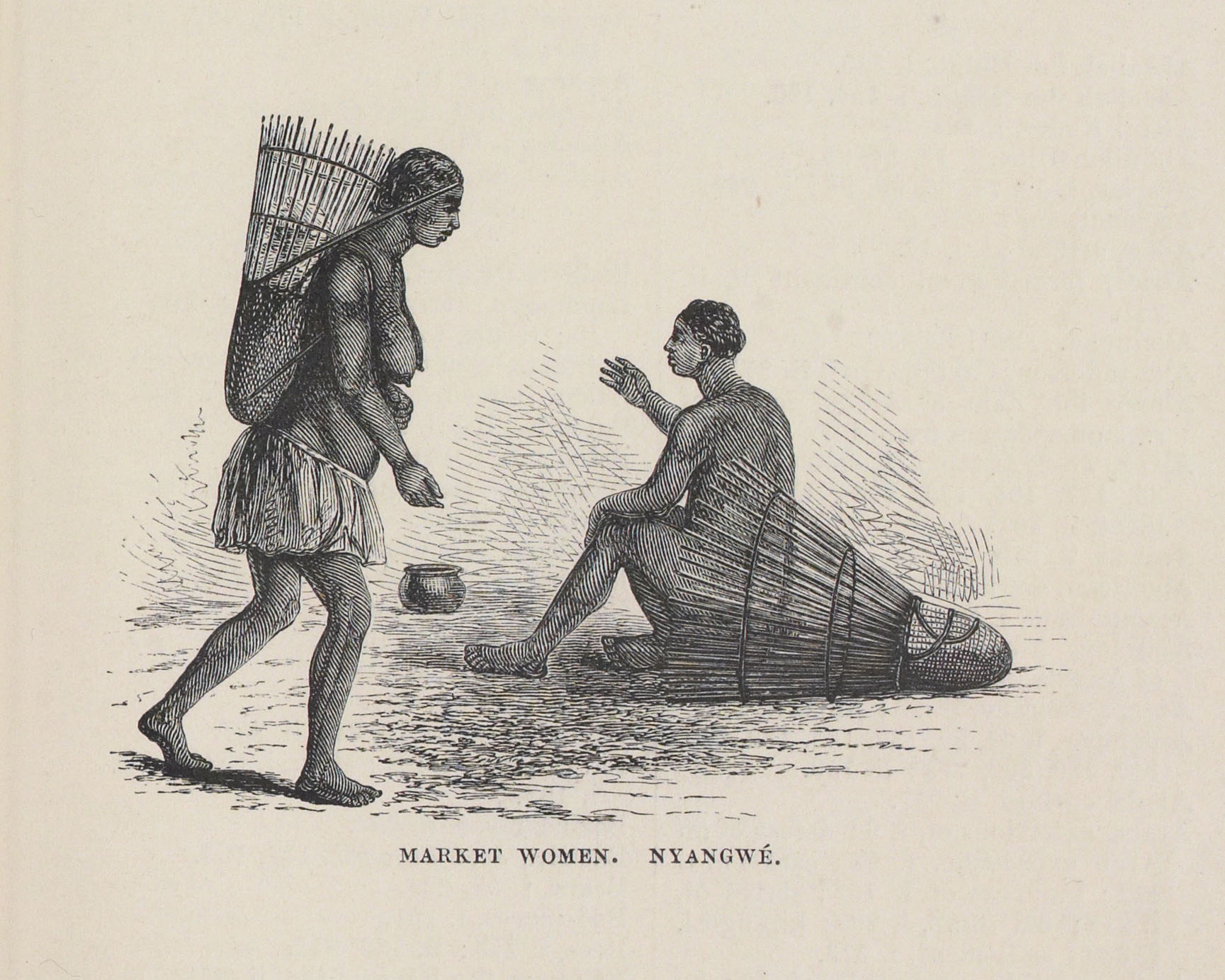

Nyangwe Market Women. Illustration from Cameron's Across Africa (1877a,1:379). Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland

For the Arabs, however, securing the cooperation of the local population served only to facilitate a larger goal: exploring the lands west and north of Nyangwe in order to find new sources of ivory and other trade goods. Nyangwe’s central location made it an ideal base and launching point, and, eventually, the settlement helped define a larger zone of Arab activity, influence, and, most importantly, slave trading (Stanley 1970:321). A succession of well-known Arab traders became associated with the settlement, including its founder Mwini Dugumbi and the notorious Tagamoio (a.k.a Mtagamoyo or Mwini Mohara), the ringleader of the Nyangwe massacre (Anon 1892, 1894). Nyangwe itself grew from a "mere Arab depot," as Stanley described it (1877-78:154), into one of the major Arab trading centers west of Lake Tanganyika by the late 1880s with a population approaching 10,000 residents (Renault 1989:148).

Its significance to Arab traders notwithstanding, Nyangwe also served as the site of an important African periodic barter market. This market functioned as a key point of contact between the fishing populations of the river and the agricultural communities based in the area around Nyangwe. Livingstone (1872d:13) noted that "The market was attended every fourth day by between 2,000 and 3,000 people." Thanks to such numbers, the market facilitated trade in a wide range of items, including slaves. During one visit to the market, Livingstone (1871f:CXV) had the opportunity to question slaves taken from at least nine different regions beyond Nyangwe. Because of Nyangwe’s location, the market also provided a crucial link between the great Luba Empire centered in the savannah lands to the south and the Lega people scattered through the rainforest to the north (Biebuyck 1973; Reefe 1981).

| Items Available at the Nyangwe Periodic Barter Market, 1871-76 DL = Livingstone; VLC = Cameron; HMS = Stanley |

|||||||

| Item | DL 1866-72 | DL 1871g | DL 1871j | DL 1872d | VLC 1874a | VLC 1877a | HMS 1878 |

| Sweet Potatoes | x | x | x | ||||

| Yams | x | x | |||||

| Sesamum | x | x | |||||

| Beans | x | x | |||||

| Cassava | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Ground-nuts | x | x | x | ||||

| Pepper | x | x | x | x | |||

| Salt | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Sugar-cane | x | x | |||||

| Vegetables for broths | x | x | |||||

| Bananas | x | x | x | ||||

| Fowls | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Pigs | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Goats | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Sheep | x | x | x | x | |||

| Fish | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Snails (dried) | x | x | |||||

| White ants | x | x | |||||

| Earthenware | x | x | x | x | |||

| Grass mats | x | x | |||||

| Grass cloths | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Powdered camwood | x | x | |||||

| Palm Oil | x | x | x | x | |||

| Spears | x | x | x | ||||

| Metal | x | x | |||||

| Slaves | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Ivory | x | x | |||||

| * Items mentioned only Livingstone: potatoes (1866-72), relishes (1866-72), clarias capensis (1866-72), grain (1866-72), cocks (1866-72), plantains (1871g) | |||||||

| * Items mentioned only by Cameron: oil palm dates (1874b), baskets (1874b), “everything produced in the country” (1877a) | |||||||

| * Items mentioned only by Stanley: (all in 1878) maize, millet, cucumbers, melons, wild fruit, palm-butter, oil-palm nuts, pine-apples, honey, eggs, parrots, palm-wine (malofu), pombé (beer), mussels and oysters from river, dried fish, whitebait, grasshoppers, tobacco (dried leaf), pipes, fishing nets, basket-work, cassava bread, copper bracelets, iron wire, iron knobs, hoes, bows and arrows, hatchets, rattan-cane staves, stools, crockery, fuel | |||||||

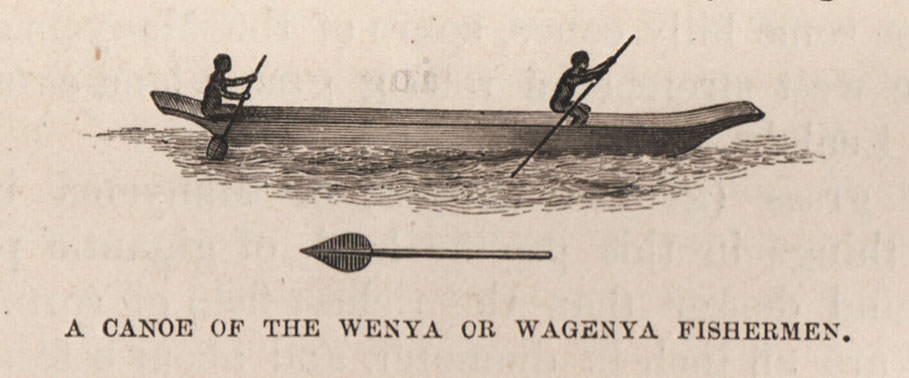

Nyangwe’s cultural and economic role alongside the rise of Arab trading in the region, therefore, ensured that the settlement facilitated interaction among a variety of groups: the Arabs and their forces; slaves transported to Nyangwe by the Arabs; the Luba and Lega communities; the diverse ethnic communities residing in the vicinity of Nyangwe; and, finally, the Wagenya fishermen, who were linked to these others groups through control of traffic on the Lualaba River. The items available for trade in Nyangwe reflected the diversity of the populations that frequented the market, and included local products such as fish – fifteen different types by Livingstone’s count (1872d:13), products transported across longer distances, and items introduced by the Arabs.

Canoes on the Lualaba Top ⤴

Livingstone stayed in Nyangwe from 30 March to 20 July 1871. Much of the time he remained free from fever and ever-ready to depart. He interviewed Arab travellers, their slaves, and local African inhabitants about local geographical details, and he considered possible travel routes. He also attended the market regularly (28 were held during his time in Nyangwe) and took great delight in watching the market sellers at their work: "[May] 12th a set in rain from Nor West did not deter the market today – people came singing and sheltered with mats" (1871f:CXXXVII).

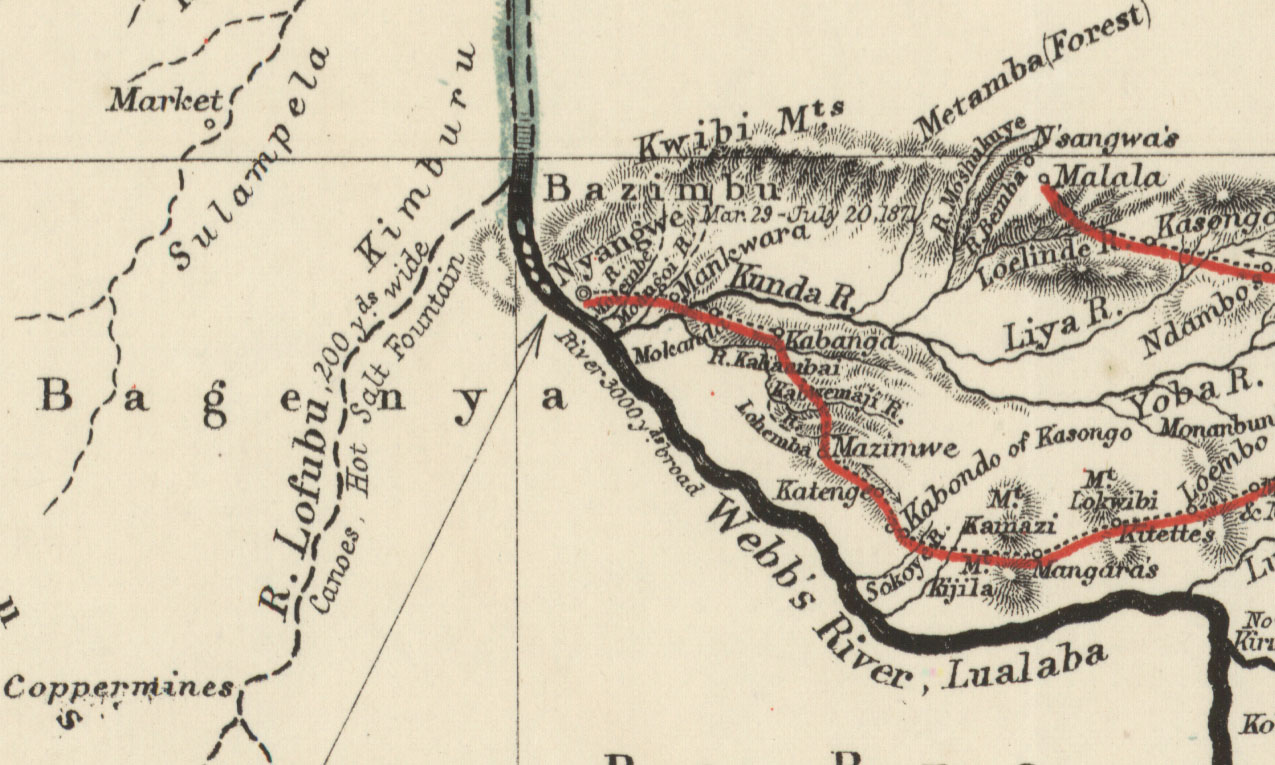

Large map from the Last Journals (Livingstone 1874), two details. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. Nyangwe was the north-western endpoint of Livingstone's travels. View or download a high-resolution image of this map.

Such moments offered a relief to his ongoing troubles in Nyangwe with the "Banian slaves," a group of liberated slaves formerly owned by Banian merchants and hired by John Kirk, the acting British Consul and Political Resident at Zanzibar, to assist Livingstone. These Banian followers (henceforth the term to be used, since the men were no longer slaves when in Livingstone's retinue) continuously aggravated Livingstone, launched forays against local inhabitants, refused to go forward in travel, and, finally, conspired to turn the inhabitants of Nyangwe against Livingstone. The behavior of these men shook Livingstone’s faith in the ability of slaves to be rehabilitated and drew a volley of invectives. Waller later cut the most vituperative of these while editing Livingstone's Unyanyembe Journal (1866-72), in particular because the comments also referenced Livingstone’s grievances against John Kirk (Helly 1987:179-81).

During these early months in Nyangwe, Livingstone also made a sustained attempt to purchase a canoe from the Wagenya fishermen of the Lualaba River. An adequate canoe was crucial for further exploration of the river. Yet the enterprise proved quite frustrating. Its unexpected culmination became one of the key incidents that Livingstone compressed and rewrote when he revised the 1871 Field Diary to produce the corresponding entries in the Unyanyembe Journal.

In April, the 1871 Field Diary indicates, Livingstone repeatedly failed to secure a canoe or even gain the trust of the local population through his own efforts. In May, he turned to the Arab trader Abed for help, and the two of them tried to negotiate for a canoe with an African chief named Kalenga. The venture not only failed, but also resulted in Livingstone being cheated of a "thousand cowries – three goats beads" when Kalenga revealed that the canoe belonged to someone else and was not his to sell in the first place (1871f:CXXXV).

A Canoe of the Wenya or Wagenya Fisherman. Illustration from Stanley's Through the Dark Continent (1878,2:116). Courtesy of Indiana University of Pennsylvania Library.

In response, Livingstone attempted to restrain his anger, especially as he knew that the Arabs were watching his every move: "It is very grievous to be cheated after losing nearly three months in the business but Kalenga has no canoe and I must not be the first to do what may be called injustice [ – ] The Arabs would like to see me using force" (1871f:CXXXV).

Yet Livingstone could not put the matter to rest. "The conduct of Kalenga to me is not be endured," he notes in the entry of 12 June. "It is the most childish impertinence because he thinks nothing will be done to him but talk as Manyema do & have done for ages” (1871f:CXXXVII). The next entry follows these developments to their conclusion:

13th chitoka = men off to force Kalenga to reason = if he refuses to refund to bind and give him a flogging – if It [sic] is entirely lost then return and get of my beads to buy another canoe down the river – Kalenga fled – (1871f:CXXXVII)

It is an astonishing turn of events, a moment that shows Livingstone attempting to harness the violent tendencies of the Banian followers – tendencies that he otherwise deplores – against a member of the local African population.

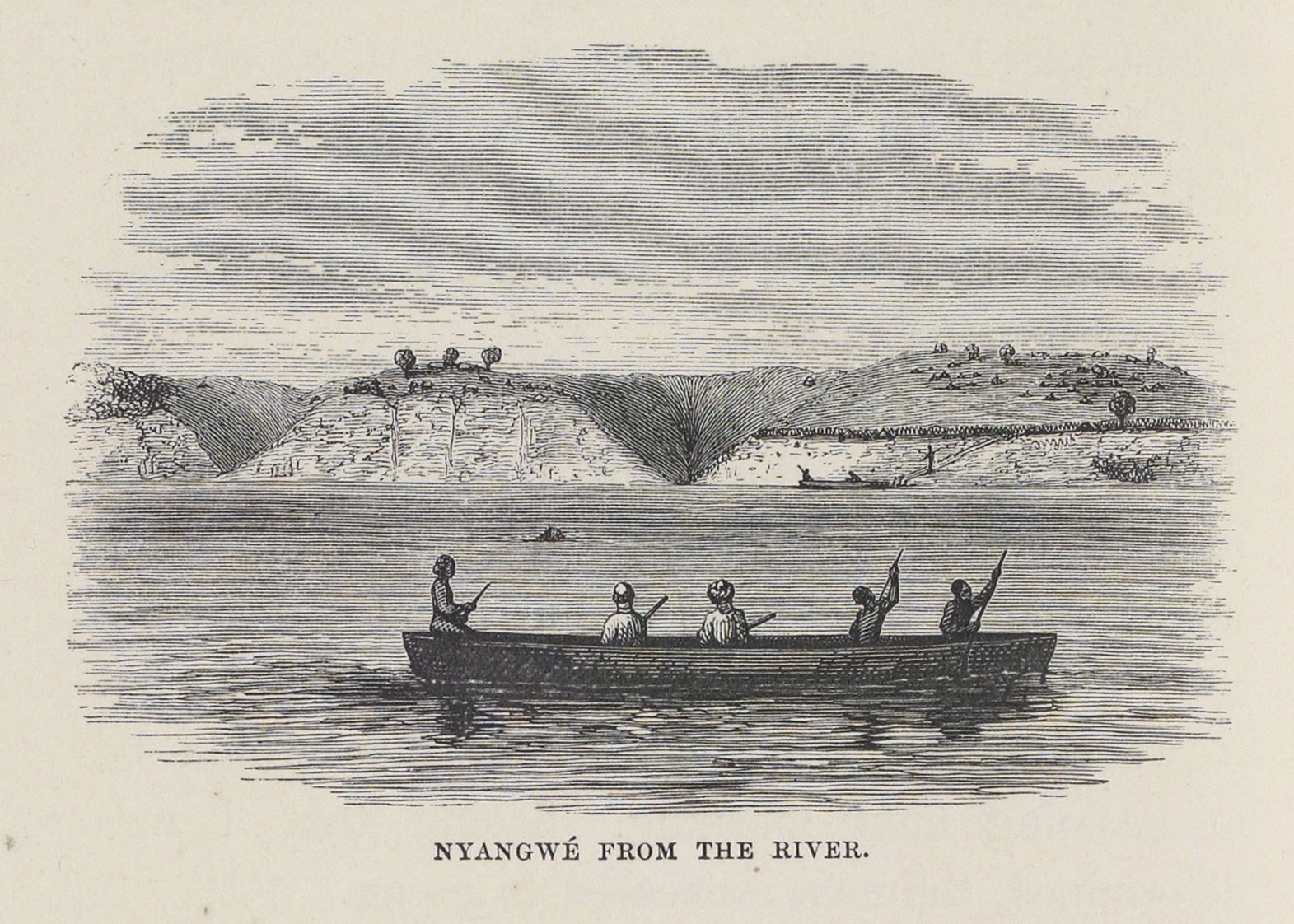

Nyangwe from the River. Illustration from Cameron's Across Africa (1877a,1:378). Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland

In the Unyanyembe Journal, Livingstone removed the Banian followers from the narrative of this incident and reduced the whole series of interactions with Kalenga to a few sentences in the 20 May 1871 entry:

Abed called Kalenga the headman who beguiled him as I soon found and delivered the canoe he had bought formally to me and went off down the Lualaba on foot to buy the Babira ivory – I was to follow in the canoe and wait for him in the River Luira but soon I ascertained that the canoe was still in the forest and did not belong to Kalenga – On demanding back the price he said let Abed come and I will give it to him – Then when I sent to force him to give up the goods all his village fled into the forest (1866-72:[680])

The language is restrained. This version lacks the immediacy of the 1871 Field Diary, and Livingstone’s revisions effectively neutralize the final turn of events. Livingstone forestalls any connection a reader might make between the general contours of this incident and the event that would soon become the defining moment of Livingstone’s time in Nyangwe.

"Unspeakable Horror" Top ⤴

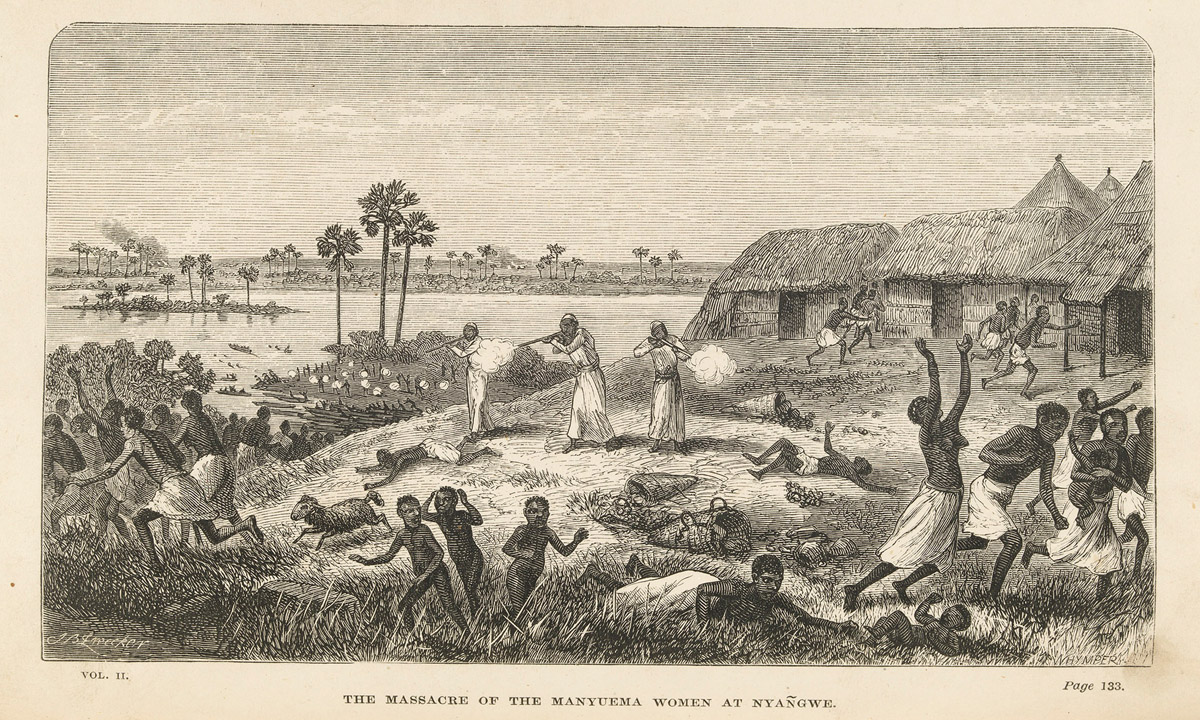

On 15 July 1871, the whole tenor of Livingstone’s experiences in Nyangwe changed dramatically. It was a market day, and Livingstone attended as always. He was just leaving when a few Arab traders (the number varies by account) entered the market carrying guns. A moment later, possibly after an argument with the sellers, the Arabs began to fire on the market goers, most of whom were women.

The local inhabitants held the market on a stretch of open land on the right bank of the Lualaba River, near a creek that flowed into the river. This creek offered a convenient place to land canoes. When the firing began, a general panic ensued. Everyone ran for the canoes, but a second group of Arabs near the creek also began to fire on the crowd. Now everyone made for the Lualaba – even those who could not swim – and threw themselves in. The Arabs continued to fire. In the ensuing chaos, many of those who avoided the gunfire got caught in the current and drowned.

The Massacre of the Manyuema Women at Nyangwe. Illustration from the Last Journals (Livingstone 1874,2:opposite 133). Courtesy of Edinburgh University Library.

All told some 400 or 500 individuals died, with others being captured by the Arabs to be made slaves. In addition, the Arabs crossed the river and began attacking and setting fire to many of the villages on the left bank. Livingstone counted 17 villages in flames. The "slaughter" (1866-72:[692]) continued into the next day.

The reasons for the attack, which came into focus only gradually, are as follows. A few days earlier Manilla, one of the head African slaves of the Arabs, went over to the left bank and sacked 10 villages of the Mohombo tribe on behalf of a Wagenya chief named Kimburu (Livingstone 1871f:CXLI). The Arabs under Dugumbe resented Manilla’s forward behaviour and attacked the market goers and Kimburu’s people in retaliation.

Nearly 70 years ago, Sir Reginald Coupland (1945:77ff.) definitively outlined the factors that prevented Livingstone from continuing his explorations forward from Nyangwe and, therefore, that led to the Livingstone-Stanley meeting. These included illness, resistance from the Banian followers, and a variety of local factors. However, no single event impacted Livingstone’s plans as profoundly and rapidly as the massacre. In the July 16 entry of the 1871 Field Diary, Livingstone writes that "the murderous assault on the market people was Hell without the fire and brimstone […] It filled me with unspeakable horror" (1871f:CLI). By July 17 he had made his decision to return to Ujiji. On 20 July he departed.

Nyangwe after its destruction by the forces of the Congo Free State in 1893 (Hinde 1895:433). Courtesy of the National Library of Scotland.

The chief perpetrator of the massacre was one Tagamoio, whom Livingstone did not mention in the 1871 Field Diary until this moment (Tagamoio does appear on the last page of the 1870 Field Diary; see 1871e:CI). He would become notorious through the published accounts of the massacre, but he escaped punishment. In fact, over the ensuing two decades Tagamoio established himself as one of the leading Arabs at Nyangwe and remained so until brought down by the forces of the Congo Free State in 1893 (Hinde 1895, 1897).

Representing the Nyangwe Massacre (1) Top ⤴

For the last 140 years, scholars and the public have relied on several accounts for the story of the Nyangwe massacre. These include one in a 14 November 1871 letter to Earl Granville (Livingstone 1872d), that of the Unyanyembe Journal (Livingstone 1866-72:[691]-[696]), another in the Last Journals (1874:132-36) and several produced by Stanley based on Livingstone’s description (Stanley 1970; 1877-78; 1878). Conversely, the account in the 1871 Field Diary (1871f:CXLVI-CXLVIII), which diverges significantly from these other narratives, has not been available until now.

The three accounts produced by Livingstone himself (1866-72, 1871f, 1872d) will be the subject of discussion here. Although Helly (1987) has written brilliantly of the editorial changes that Horace Waller made to the Unyanyembe Journal to produce the Last Journals, her observations do not cover the case of the Nyangwe massacre. Only minor editorial changes, such as capitalization and punctuation, distinguish the Unyanyembe Journal and Last Journals narratives of the massacre. The narrative shape of the 1871 letter, written a few months after the massacre, also bears a strong affinity to the Unyanyembe Journal and Last Journals texts.

Photograph of David Livingstone, 1857. Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Object images used by permission. May not be reproduced without the express written consent of the National Trust for Scotland, on behalf of the Scottish National Memorial to David Livingstone Trust.

In the case of the 1871 letter and Unyanyembe Journal, Livingstone writes with the full benefit of hindsight. The opportunity to reflect allows him to organize his narrative and to present the massacre as a fully coherent set of events. As a result, the 1871 letter and Unyanyembe Journal narratives are reflective and written primarily in the past tense. Livingstone details the motives of the principal actors, with Tagamoio’s activities throughout the massacre receiving extended attention. He also elaborates wherever necessary in order to give a full picture of events and their underlying causes: "The wish to make an impression in the country as to the importance and the greatness of the new comers was the most potent motive" (1866-72:[695]).

Most importantly, from the start Livingstone carefully represents his own reactions, and his efforts on behalf of the local population. For instance, he offers an account for his own lack of intervention: "My first impulse was to pistol the murderers but Dugumbe protested against my getting into a blood feud and I was thankful afterwards that I took his advice" (1866-72:[694]). Livingstone also notes how he directed his followers to rescue one group of Africans: "I sent men with our flag to save some for without a flag they might have been victims" (1866-72:[695]). Livingstone’s Arab associate Dugumbe likewise appears in a favorable light. Dugumbe shows remorse for the massacre (1866-72:[698]) and attempts to rescue a number of Africans: "Dugumbe put people into one of the deserted vessels to save those in the water – and saved twenty-one" (1866-72:[693]).

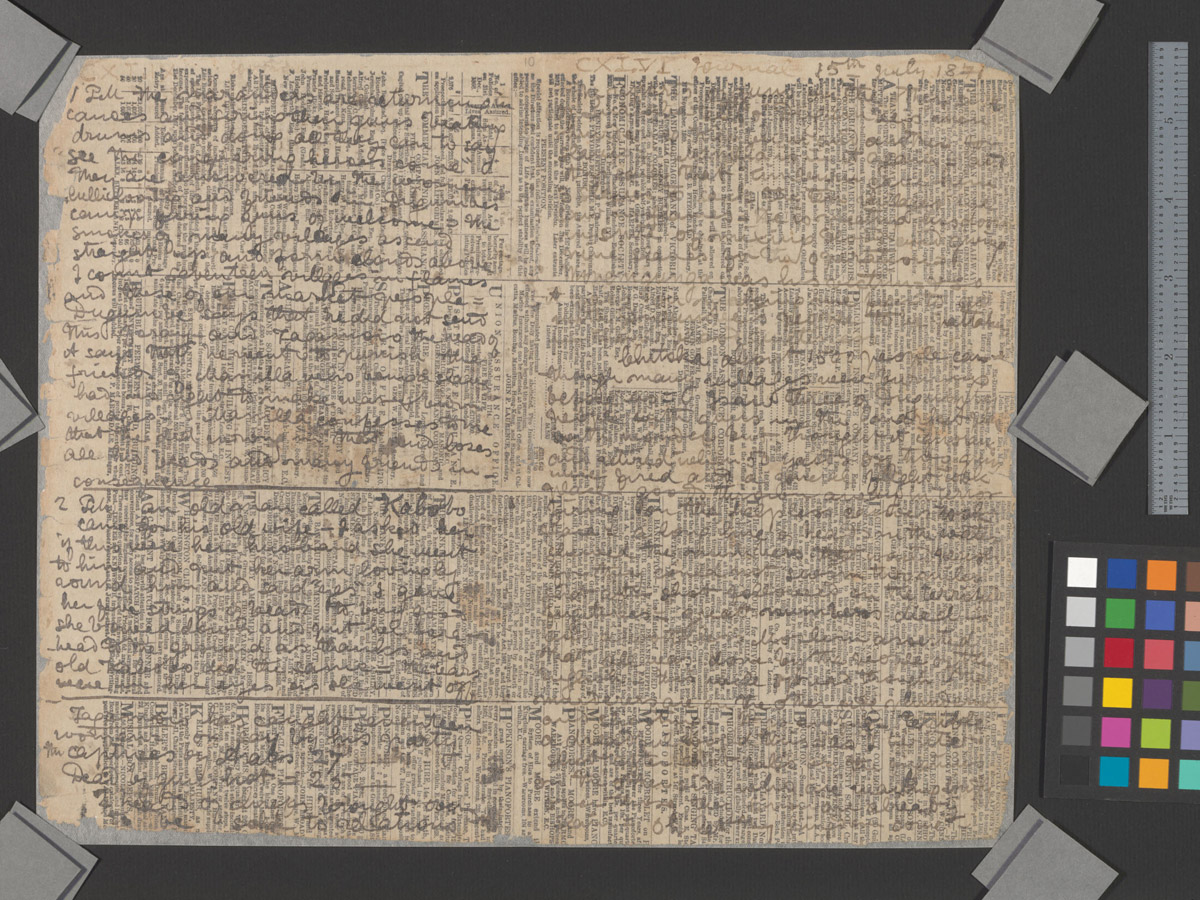

An image of two pages of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871f:CXLIX-CXLVI). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The right-hand page contains the opening account of the massacre. The left-hand page continues a later part of the narrative.

The 1871 Field Diary presents the massacre in a radically different manner. The massacre has only begun when Livingstone starts writing, and it continues to unfold as Livingstone composes. This singular circumstance has a wide range of implications. Livingstone takes his readers into the midst of the massacre with prose that is remarkably compressed, vivid, and immediate:

15th July 1871 The reports of guns on the other side of Lualaba tell of Dugumbe's men murdering Kimburu and another for slaves = Manilla is in it again = and it is said that Kimburu gave him 3 slaves to sack the ten villages we saw in flames – He is meeting his doom in spite of mixing blood and giving nine slaves for the operation = Moenemgunga was his victim = & so it goes on making me fear to go with Dugumbe's people to be partakers in their blood guiltiness (1871f:CXLVI).

This is a private document, legible to the writer, but not necessarily to others. Livingstone shows much but tells little. He introduces individuals without gloss and tersely goes from cause to effect. Manilla, it appears, is not only leading the foray, but in doing so has broken his pact of friendship with Kimburu.

The Unyanyembe Journal offers a strikingly different account of these opening moments:

15th July 1871 The reports of guns on the other side of the Lualaba all the morning tell of the people of Dugumbe murdering those of Kimburu and others who mixed blood with Manilla – Manilla is a slave and how dared he to mix blood with chiefs who could only have made friends with free men like them – Kimburu gave Manilla three slaves and he sacked ten villages in token of friendship – He proposed to give Dugumbe nine slaves in the same operation But Dugumbe's people destroy his villages and shoot and make his people captives to punish Manilla - make an impression in fact in the country that they alone are to be dealt with - Make friends with us and not with Manilla or any one else (1866-72:[691]-[692]).

Livingstone is not just editing; he is reconfiguring his representation of reality, and has begun to write with an audience in mind. He elaborates and explains wherever necessary and ends by providing direct access to the minds and the motives of the principal perpetrators. We discover that Dugumbe’s people – but not Manilla – bear the responsibility for the attack.

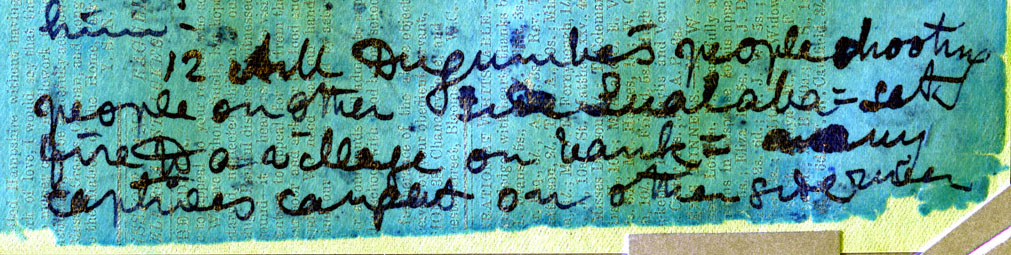

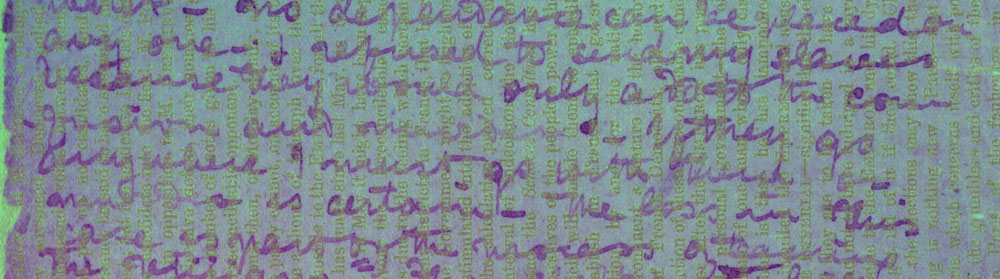

A processed spectral image of a page of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871f:CXLVIII spectral_ratio), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. In the segment shown here, Livingstone makes the unprecedented shift from daily to hourly entries.

In fact, a comparative look at the descriptions of the massacre in the 1871 Field Diary and Unyanyembe Journal reveals that Livingstone has carried out major revisions in producing the latter. For example, Livingstone has made the entries for 15 and 16 July in the Unyanyembe Journal nearly twice as long as those of the 1871 Field Diary. In many instances he has significantly reconfigured the order of the extracts taken from the 1871 Field Diary. He has added a series of descriptive passages to the narrative of the Unyanyembe Journal. In addition, ink analysis of the relevant 1871 Field Diary pages reveals a poignant detail of composition otherwise lost in Livingstone’s Unyanyembe Journal transcription: namely, that in recording the massacre, Livingstone switched to his remaining reserve of iron gall ink in an attempt to ensure the permanence of his words (see Livingstone's Composition Methods).

More importantly, the narrative of the 1871 Field Diary unfolds with all the uncertainty of lived experience, especially under such circumstances as a massacre. Livingstone expends much energy in trying to understand developing events, identifying the culprits, and figuring out their motives. The prose does not immediately clarify the relationship between the Nyangwe massacre and the village attacks on the west bank. Moreover, Livingstone fails to exculpate Dugumbe and doesn't discover the leading role of Tagamoio until well into the 16 July entry (1871f:CXLIX). In fact, that 16 July moment represents the first time Livingstone even names Tagamoio. By contrast, in the Unyanyembe Journal version Tagamoio receives extended attention from the middle of the 15 July entry onward.

Representing the Nyangwe Massacre (2) Top ⤴

As a result, the 1871 Field Diary offers a fascinating glimpse into Livingstone’s mind at the moment of the greatest crisis in his final travels. Despite his familiarity with slavery in Africa, the scale of the Nyangwe massacre exceeds his range of experience, and he struggles to come to terms with the event. Resistance by the Arab traders to clarify the underlying motives for the massacre, the chaotic order of Livingstone’s successive 15 July diary entries, and his unprecedented shift to hourly entries on 16 July all underscore his deep vulnerability and confusion at the moment of the massacre.

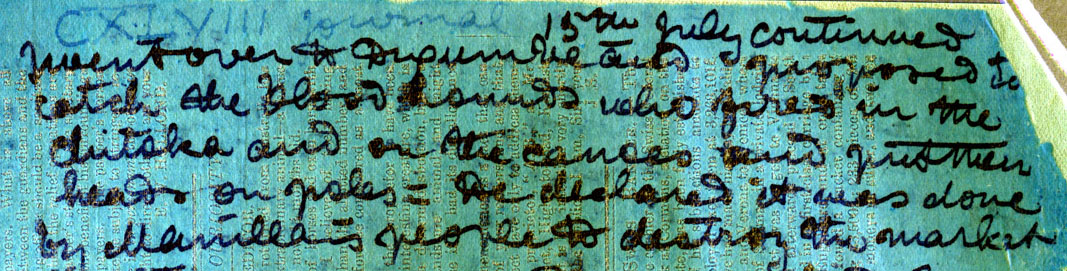

Still other moments reveal Livingstone’s conflicted thoughts regarding an appropriate response to the violence and his potential culpability for at least some of it. For instance, Livingstone assists whatever African villagers come to him for help, as both the 1871 Field Diary and Unyanyembe Journal make clear. In anger, he also considers an extreme, out of character response: "I went over to Dugumbe and proposed to catch the bloodhounds who fired in the chitoka and on the canoes and put their heads on poles" (1871f:CXLVIII; see above for the edited Unyanyembe Journal version).

A processed spectral image of a page of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871f:CXLVIII spectral_ratio), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. This segment captures part of Livingstone's original response to the massacre. In transcribing the 1871 Field Diary into the Unyanyembe Journal (1866-72), Livingstone considerably changed the representation of such raw emotion.

Yet Livingstone also makes decisions of questionable merit, as when he sends his men with a flag to assist Manilla’s brother (1871f:CXLVII), not local villagers as the Unyanyembe Journal version would have it. More significantly, the structuring of events in the 1871 Field Diary foregrounds the possible role of Livingstone’s Banian followers in the massacre.

As noted above, Livingstone had previously instructed the Banian followers to bind and flog the headman Kalenga when the latter "bamboozled" Livingstone out of the payment for a canoe (1871f:CXXXIV). Yet Livingstone compressed this incident and moved it away temporally from the Nyangwe massacre when producing the Unyanyembe Journal. It is not clear why Livingstone made this revision, although he may have feared that readers of his Journal might believe that his violence towards Kalenga offered some sort of model for the Arabs. Livingstone notes as much in the 1871 Field Diary: "I must not be the first to do what may be called injustice [ – ] The Arabs would like to see me using force" (1871f:CXXXV).

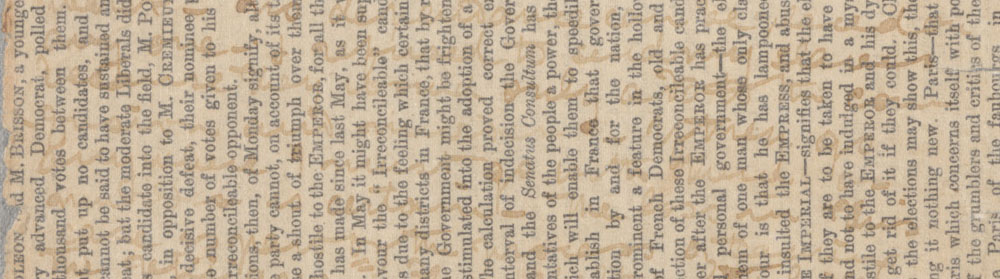

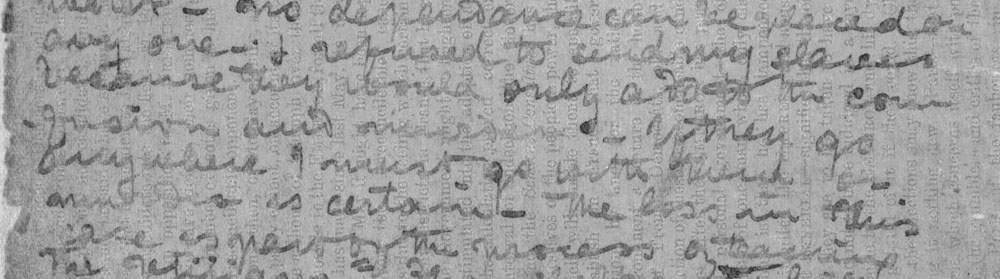

In writing up the Unyanyembe Journal, Livingstone also made other changes to his representations of the Banian followers. For instance, he deliberately revised one particularly damning passage from 30 April 1871. In the 1871 Field Diary, Livingstone records a report of some Arab traders a few days distant being in need of assistance. Although called on to send help to them, Livingstone writes, "I refused to send my slaves because they would only add to the confusion and murder – If they go anywhere I must go with them or murder is certain" (1871f:CXXIII).

(Top) Natural light and (center and bottom) two processed spectral images of a page of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871f:CXXIII color, pcar621r, and pcar621r_pcolor), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. In this segment of the 1871 Field Diary, Livingstone describes the murderous tendencies of his Banian followers. The revised version of the segment in the Unyanyembe Journal (1866-72) diminishes Livingstone's original sentiments and places them at a greater temporal remove by assigning this text to an earlier date.

In the Unyanyembe Journal, he incorporates this comment into an earlier entry, 25 April, and rewords it as follows: “I declined – because no matter what charges I gave my Banian slaves would be sure to shed human blood” (1866-72:[671]). Most obviously, such revisions help diminish the original sentiments, and there is the temporal distancing once more. Livingstone’s motives for these revisions again remain unknown. Certainly the original passage is at odds with his usual complaints about the resistance of the slaves to further exploration and their attempts to slander him before the inhabitants of Nyangwe – relatively mild complaints when compared to the unrevised passage. Or, put another way, Livingstone’s overall presentation of the Banian followers becomes more benign – however contemptuous it might still seem – when the passage regarding their murderous tendencies is reworded.

In the Unyanyembe Journal, the consistency of such "benign" representations serves at least one significant narrative purpose. It gives Livingstone grounds to refute the accusation leveled by Arab slave traders that the Banian followers had a role in carrying out the Nyangwe massacre:

Two wretched Moslems asserted "that the firing was done by the people of the English" I asked one of them why he lied so and he could utter no excuse – no other falsehood came to his aid as he stood abashed before me and telling him not to tell palpable falsehoods left him gaping (1866-72:[694]).

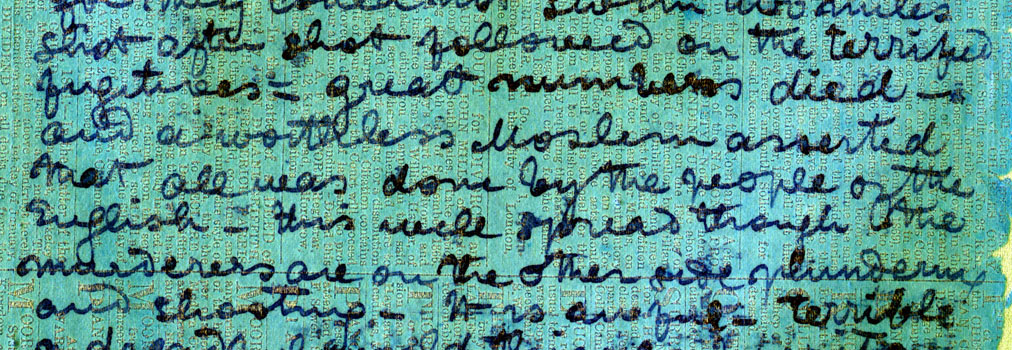

In the 1871 Field Diary, the representation of this moment and Livingstone’s response is much more ambiguous:

shot after shot followed on the terrified fugitives = great numbers died – and a worthless Moslem asserted that all was done by the people of the English – This will spread though the murderers are on the other side plundering and shooting – It is awful – terrible (1871f:CXLVI)

Although Livingstone’s prose may imply a refutation, explicitly he fails to foreclose the possibility that his slaves took part in the Nyangwe massacre. Moreover, the difference between the two versions again helps to foreground a larger pattern of apparent revision.

A processed spectral image of a page of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871f:CXLVI spectral_ratio), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. Livingstone significantly revised this passage in the version wrote in the Unyanyembe Journal (1866-72).

Conclusion Top ⤴

Dorothy Helly has written eloquently of the public impact of Livingstone’s description of the Nyangwe massacre in the 1871 letter version:

Livingstone’s vivid characterization of the wholesale bloodshed that could disrupt daily life in Africa as a consequence of the slave trade came at a crucial moment. His words fed into a well-planned campaign recently launched within antislavery circles to stir up public clamor for ending the seaborne slave trade that supplied the Middle East and the island of Zanzibar and its sources on the adjacent east coast of Africa (Helly 1987:26).

British abolitionists achieved this objective just one year after the publication of Livingstone’s letter, with the signing in June 1873 of the treaty between Britain and the Sultan of Zanzibar for the suppression of the slave trade. Livingstone and his cause "would thereafter remain synonymous, just as Wilberforce’s name had come to symbolize the antislavery cause on the Atlantic coast of Africa earlier in the century" (Helly 1987:27).

| (Left; top in mobile) Natural light and (right; bottom) processed spectral images of a page of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871f:CXXXIII [v.1] color and spectral_ratio), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. This is one of the most difficult pages of the diary to transcribe, even with the benefit of spectral image processing. |

The 1871 Field Diary – only now made available through spectral imaging and processing – opens a new dimension in our understanding of these historical developments. It is not unreasonable to suppose, given the revisions cited above, that Livingstone’s slaves had a part in inciting the Nyangwe massacre or, at least, that Livingstone feared that their actions and his own had helped launch the chain of violent events that led to the massacre. As a result, he sought to downplay these points when revising the 1871 Field Diary to produce the Unyanyembe Journal.

Of course, we cannot confirm this hypothesis without the discovery of more evidence. However, if true, it would mean that by bringing these Banian followers to Nyangwe, Livingstone – however inadvertently – helped occasion the horrific event that transformed the trajectory of his final travels in Africa and that established the image of the tireless abolitionist crusader that we remember today.

Works Cited Top ⤴

[View the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project's full bibliography.]

Anon. 1892. "Les Arabes du Haut Congo." Le Congo Illustré 1: 130-31.

Anon. 1894. "Les Chefs Arabes du Haut Congo." Le Congo Illustré 3: 17-20, 30-32, 38-39, 46-47, 50-51.

Biebuyck, Daniel. 1973. Lega Culture: Art, Initiation, and Moral Philosophy among a Central African People. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Bridges, Roy C. 1973. "The Problem of Livingstone's Last Journey." In Proceedings of a Seminar Held on the Occasion of the Centenary of the Death of David Livingstone at the Centre of African Studies, University of Edinburgh, 4th and 5th May 1873, 163-85. Edinburgh: Centre of African Studies, University of Edinburgh.

Cameron, Verney Lovett. 1874a. Notebook (July-Sept. 1874). Acc.10120. National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Cameron, Verney Lovett. 1874b. Journal II (June-Sept. 1874). Acc.10120. National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Cameron, Verney Lovett. 1877a. Across Africa. 2 vols. London: Dalby, Isbister & Co.

Ceulemans, P. 1959. La Question Arabe et le Congo (1883-1892). Bruxelles: Académie Royale des Sciences Coloniales, Classe des Sciences Morales et Politiques.

Coquery-Vidrovitch, Catherine. 2005. The History of African Cities South of the Sahara from Origins to Colonization. Princeton, NJ: Markus Wiener Publishers.

Coupland, Reginald. 1945. Livingstone's Last Journey. London: Collins.

Helly, Dorothy O. 1987. Livingstone's Legacy: Horace Waller and Victorian Mythmaking. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press.

Herodotus. 1987. The History. Translated by David Grene. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hinde, Sidney Langford. 1895. "Three Years' Travel in the Congo Free State." The Geographical Journal 5 (5): 426-46.

Hinde, Sidney Langford. 1897. The Fall of the Congo Arabs. London: Methuen & Co.

Jeal, Tim. 1973. Livingstone. London: Heinemann.

Livingstone, David. 1857. Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa. London: John Murray.

Livingstone, David. 1866-72. Unyanyembe Journal. 28 Jan. 1866-5 Mar. 1872. 1115. David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1870e. Fragment of 1870 Field Diary (X-XIII). 10 Oct. 1870. MS. 10703, ff. 1-2. National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1871f. Fragment of 1871 Field Diary (CII-CLXIII). 23 Mar. 1871-11 Aug. 1871. 297b, 297c. David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1872a. Letter to Lord Stanley. 15 Nov. 1870. Parliamentary Papers 70 (C-598):1-5.

Livingstone, David. 1872d. Letter to Lord Granville. 14 Nov. 1871. Parliamentary Papers 70 (C-598):10-15.

Livingstone, David. 1874. The Last Journals of David Livingstone in Central Africa, from 1865 to His Death, edited by Horace Waller. 2 vols. London: John Murray.

Livingstone, David. 1879. Letter to John Livingstone. Apr. 1870. In Life and Explorations of David Livingstone, LL.D., D.C.L., The Great Missionary Explorer in the Interior of Africa, by John S. Roberts, 473-81. Philadelphia: John E. Potter & Co.

Murchison, Roderick Impey. 1864-65. "Address to the Royal Geographical Society." Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society 9 (5): 195-274.

Reefe, Thomas O. 1981. The Rainbow and the Kings: A History of the Luba Empire to 1891. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Renault, François. 1989. "The Structures of the Slave Trade in Central Africa in the 19th Century." In The Economics of the Indian Ocean Slave Trade in the Nineteenth Century, edited by William Gervase Clarence-Smith, 146-65. London: Cass. 1989.

Stanley, Henry Morton. 1876-77. Field Notebook, labeled "Aug 21d 1876" (21 Aug. 1876 - 3 Mar. 1877). Musée Royal de l'Afrique Centrale, Tervuren.

Stanley, Henry Morton. 1877-78. "On His Recent Explorations and Discoveries in Central Africa." Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society 22 (2): 144-166.

Stanley, Henry Morton. 1970. Stanley's Despatches to the New York Herald. Edited by Norman R. Bennett. Boston: Boston University Press.

![Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_013723_0001-new-carousel_0.jpg)

![Processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's "Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal" (Livingstone 1870a:[3] pseudo_v4_BY), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's "Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal" (Livingstone 1870a:[3] pseudo_v4_BY), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000211_0003_pseudoBY_940_by_592-carousel.jpg)

![David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, [1869], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland: CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, [1869], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland: CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_003006_0001-new-carousel_0.jpg)

![An image of a page of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871f:CXXXIII [v.1]), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871f:CXXXIII [v.1]), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/livingstone-in-1871/liv_016044_0001.jpg)

![A processed spectral image of a page of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871f:CXXXIII [v.1] spectral_ratio), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/). A processed spectral image of a page of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871f:CXXXIII [v.1] spectral_ratio), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/scotland/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/livingstone-in-1871/liv_016045_0001-1200.jpg)