The Manuscript of the 1871 Field Diary

Cite page (MLA): Wisnicki, Adrian S. "The Manuscript of the 1871 Field Diary." Debbie Harrison, ed. In Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary. Adrian S. Wisnicki, dir. Livingstone Online. Adrian S. Wisnicki and Megan Ward, dirs. University of Maryland Libraries, 2017. Web. http://livingstoneonline.org/uuid/node/9c4e1bbc-bdba-4fc9-a213-f7fb7152585c.

This section provides an overview of the strategies Livingstone employed in composing the 1871 Field Diary and the long-term consequences of those strategies. The section also defines the scope of the present edition and develops a history of the 1871 Field Diary manuscript from the nineteenth century to the present.

The Manuscript: An Overview Top ⤴

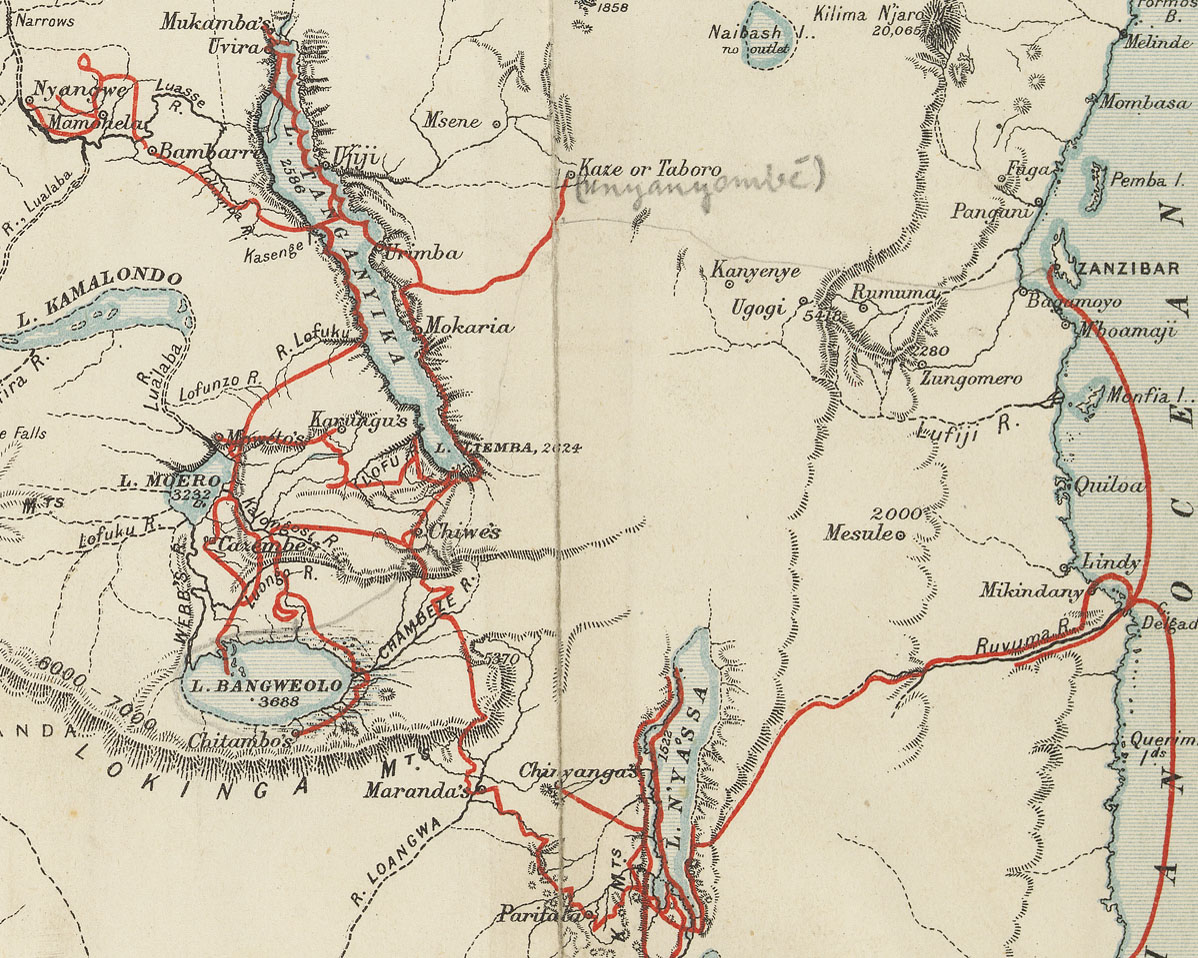

The manuscript of Livingstone’s 1871 Field Diary forms the last third of a longer sequence of manuscripts that record Livingstone’s travels in Manyema, a region that today lies in the eastern part of the Democratic Republic of Congo. These manuscripts encompasses over 160 numbered pages (the 1870 and 1871 Field Diaries) as well as several unnumbered fragments (Clendennen and Cunningham 1979:275-77, Field Diaries 34-39).

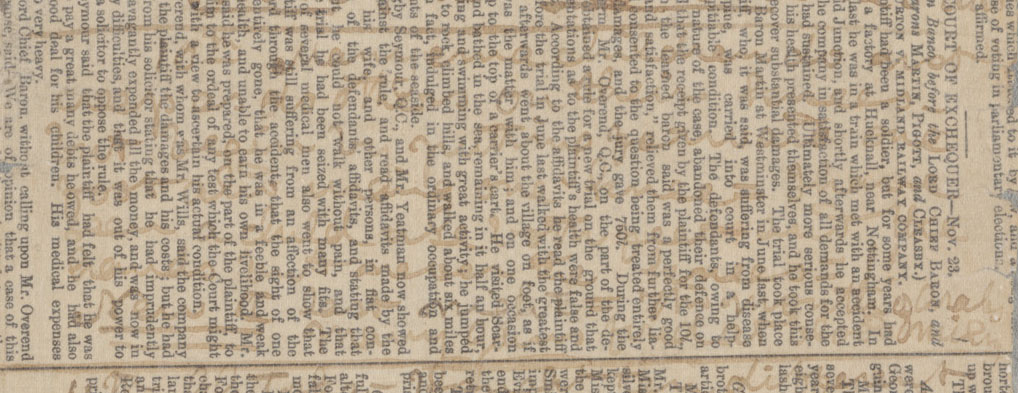

Small map from the Last Journals (Livingstone 1874), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland. The map shows the approximate extent of Livingstone's final travels. View or download a high-resolution image of this map.

During his last expedition (1866-73), Livingstone usually used small "pocket-books" or "metallic note-books" to keep his diary (Waller, in Livingstone 1874,1:iv). When time permitted, Livingstone expanded the notes in the pocket-books, while copying them over into the Unyanyembe Journal (1866-72), a single large volume that posthumously became the basis of the Last Journals (1874). Livingstone filled thirteen pocket-books in the years before his meeting with Stanley (1866-71) and an additional four during and after his time with Stanley (1871-73). The Unyanyembe Journal and all of the pocket-books (numbered by Livingstone from I to XVII) were brought back to Britain and survive to the present day (Clendennen and Cunningham 1979:273, 275-76, Journal 11 and Field Diaries 14-30; Helly 1987:64-65,130).

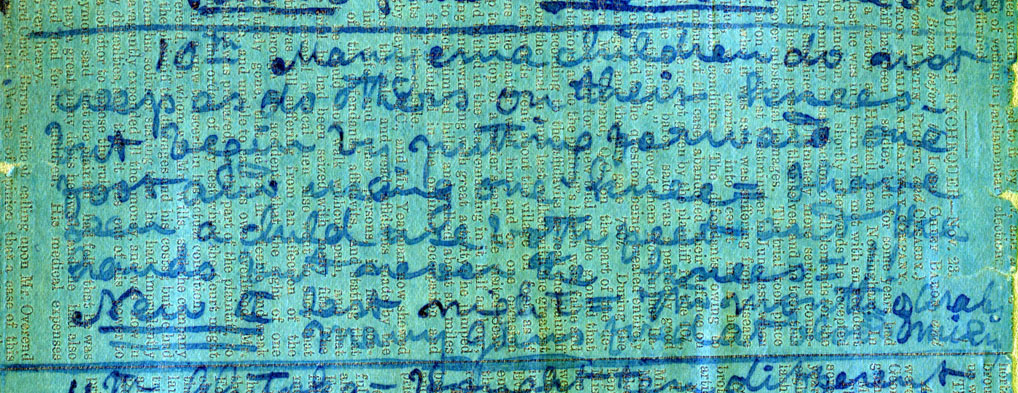

However, Livingstone began to run low on pocket-books while traveling in Manyema. To compensate, he continued to write in pocket-book XIII (28 June 1869-25 Feb. 1871), but also began to compose the 1870 and 1871 Field Diaries (17 Aug. 1870-3 Nov. 1871) using whatever paper he had on hand. These diaries are written over pages from an unidentified book of sermons, a map of Lake Albert from the Journal of the Royal Geographical Society, sheets from the Pall Mall Budget (21 Aug. 1869) and The Standard (24 Nov. 1869), and various old envelopes and enclosures. When a page already had printed text on it, Livingstone turned the page ninety degrees clockwise or counter-clockwise and wrote at a perpendicular angle to the printed text. In this way, he created a series of diary pages that have both "undertext" (the printed text) and "overtext" (Livingstone’s handwritten text). Once his supplies ran low and he was unable to create iron gall ink, Livingstone resorted to using ink made from a local African clothing dye that he called "Zingifure."

An image of two pages of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871f:CLIX-CXXXVI). Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. Livingstone uses iron gall ink for the left-hand page, Zingifure ink for the right.

Such expedients have rendered the 1870 and 1871 Field Diaries unique among Livingstone’s diaries. The physical appearance of the diaries strikingly captures the extreme and arduous circumstances under which Livingstone lived and travelled in this period of his life. Today the 1871 Field Diary in particular is in a fragile state: its pages are crumbling, and large portions of Livingstone’s handwritten text have become illegible due to fading, blotting, water damage, and other problems. Even when visible, Livingstone’s words are obscured by the printed texts over which he wrote. As a result, the manuscript of the 1871 Field Diary poses considerable challenges for its readers, especially as large segments of the diary are all but invisible to the naked eye.

(Top) Natural light and (bottom) processed spectral images of a page of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871f:CXLIV color and spectral_ratio), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. These images illustrate the significant difference between the legibility of Livingstone's text in the natural light and processed spectral images.

Scope of the Present Edition Top ⤴

▲ The Nyangwe Segment of the 1871 Field Diary (23 Mar.-11 Aug. 1871). This portion of the diary (Livingstone 1871f) records Livingstone’s journey from the village of Kasongo, an Arab settlement near the Lualaba River, to the village of Nyangwe (23-30 March 1871), his entire sojourn in Nyangwe (30 Mar.-20 July 1871), and the initial part of his return journey to Ujiji (20 July-11 Aug. 1871).

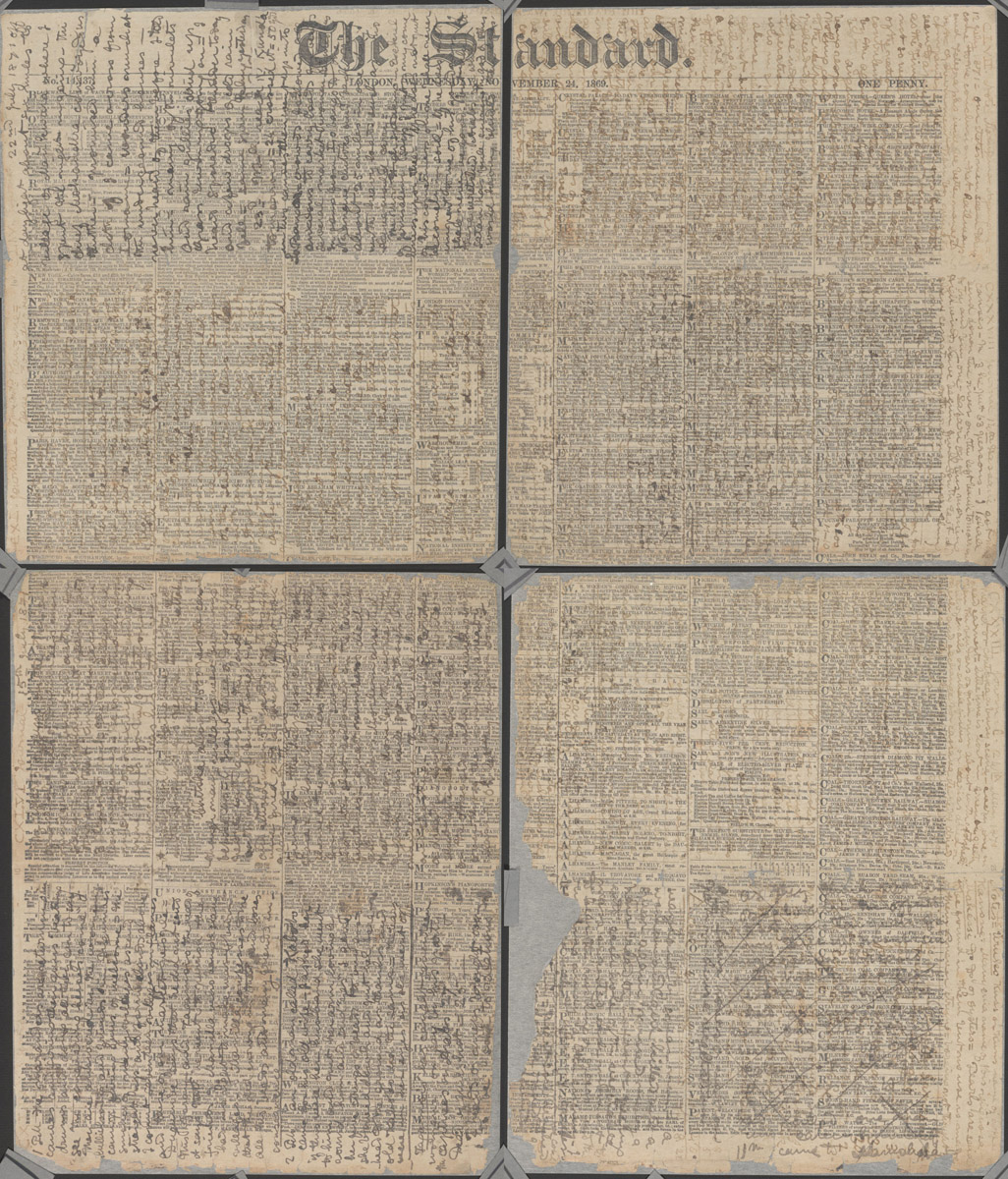

This segment consists of 34 folia. Livingstone has written the diary entries in this segment across the pages of a single, eight-page issue of The Standard (London) of 24 November 1869, which he cut up into 16 smaller leaves.

Bonus: View or download high-resolution images provided by the National Library of Scotland of a clean copy of the 24 November 1869 issue of The Standard

![An image of a page of the Letter from Bambarre (Livingstone 1871c:[1]). Images copyright Peter and Nejma Beard. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of a page of the Letter from Bambarre (Livingstone 1871c:[1]). Images copyright Peter and Nejma Beard. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/the-manuscript-the-1871-field-diary/liv_016050_0001.jpg)

An image of a page of the Letter from Bambarre (Livingstone 1871c:[1]). Image copyright Peter and Nejma Beard. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. Livingstone writes to Waller regarding the copy of The Standard that the latter sent.

Livingstone received the newspaper from his friend and future editor Horace Waller along with 3 letters dated October, November, and December 1869 and a proof copy of The Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society, 14.1 (8 Nov. 1869) on 4 February 1871. Livingstone notes these details in the Letter from Bambarre, a letter to Waller of 5 February 1871, which we have published in a separate multispectral critical edition.

The set of folia comprising this segment is complete: Livingstone’s numbering is continuous and the individual folia can be reassembled to form the entire eight-page newspaper. Each of the folia, with four exceptions, contains two adjacent, but not continuous pages of the diary. All together there are 64 numbered diary pages. Livingstone has numbered the diary pages consecutively in Roman numerals from CII to CLXIII (both CXXXII and CXXXIII are repeated).

The first page of The Standard (24 Nov. 1869), reconstructed from the folia of the 1871 Field Diary and showing Livingstone's overtext. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. The entry covering the Nyangwe massacre is the second page up from the lower left-hand corner. Download a high-resolution image of this reconstruction.

Although the leaves of this segment are now disassembled, their layout sequence indicates that Livingstone originally assembled the leaves into two "copy-books" (Waller, in Livingstone 1874,2:114n.). Each copy-book consisted of eight leaves (with two diary pages per folio, or four diary pages per leaf) placed one on top of the other, then folded along the middle to make a 32-page copy-book. It is not clear if Livingstone pre-numbered all the diary pages, but there is evidence that he pre-numbered at least some of them (see Livingstone's Composition Methods). Whatever the case, at some point the leaf containing CXIX-CXVI (recto) and CXVII-CXVIII (verso) was torn along the middle, and one leaf became two, each with only a single diary page per side:

first leaf: CXVI (recto) / CXVII (verso)

second leaf: CXIX (recto) / CXVIII (verso)

As a result, this portion of the diary consists of 34 folia containing 64 diary pages, rather than 32 folia as would be expected.

![An image of two pages of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871f:CIII-CXXXII [v.1]), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). An image of two pages of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871f:CIII-CXXXII [v.1]), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/).](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/the-manuscript-the-1871-field-diary/liv_016052_0001.jpg)

An image of two pages of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871f:CIII-CXXXII [v.1]), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre. As relevant, copyright Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported. In this image, the heat-set document repair tissue applied to this part of the 1871 Field Diary appears as a faint white film over the printed text. The tissue is particularly visible where it extends past the crumbling edges of the manuscript page.

Finally, it is worth noting that all the leaves of this segment have been laminated with a heat-set document repair tissue by the Stirling University Library Conservation Unit. The Unit is known to have treated and surveyed other paper items at the David Livingstone Centre, and held the 1871 Field Diary from about March 1986 to April 1987. This tissue had no impact on the spectral imaging and processing of the diary pages in 2010-11.

▲ Additional Diary Pages (11 Aug.-3 Nov. 1871). The second, fragmentary part of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k, 1871l, 1871m) picks up where the Nyangwe portion leaves off and continues the narrative of Livingstone’s journey back to and arrival in Ujiji (11 Aug.-3 Nov. 1871). This part ends just before the famous Livingstone-Stanley meeting. In fact, in one of the last entries Livingstone records a rumour he has heard about Stanley’s approach: "26th News from Garaganza many Arabs killed – road shut up – one Englishman there" (1871m:[1]). The leaves of this part of the diary are held by the David Livingstone Centre, the National Library of Scotland, and the Weston Library, Oxford.

![An image of a page of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871m:[1]), detail. Images copyright The Bodleian Library, University of Oxford. Used by permission. An image of a page of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871m:[1]), detail. Images copyright The Bodleian Library, University of Oxford. Used by permission.](/sites/default/files/spectral-imaging/the-manuscript-the-1871-field-diary/liv_016053_0001.jpg)

An image of a page of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871m:[1]), detail. Images copyright The Bodleian Library, University of Oxford. Used by permission. In this passage, Livingstone records the approach of Henry M. Stanley.

The folia are written on various envelopes and enclosures sent to Livingstone during his travels (see Livingstone's Composition Methods for additional information). It appears that this part is incomplete. Livingstone has not numbered the folia, but there are significant chronological gaps. The surviving folia span the following dates:

Livingstone 1871k: 11 Aug.-9 Sept. 1871

Livingstone 1871l: 28 Sept.-7 Oct. 1871

Livingstone 1871m: 23 Oct.-3 Nov. 1871

Livingstone stacked the two leaves under 1871k and folded them in half to make an eight-page copy-book. Four consecutive pages of this copy-book contain diary entries, while the remaining four (also consecutive) – which were composed both before and much later than the embedded diary entries (at least 10 Mar. 1871-15 Nov. 1871) contain various calculations and astronomical observations.

The Unyanyembe Journal (1866-72), which Livingstone wrote up from his field diaries, does contain entries for some of the missing dates, a point which suggests that there may have been other diary fragments that have not survived. Furthermore, the opening of the first page under 1871l – "28 Septr 1871 cont = Journal" – suggests that this entry continues from a previous page that has not survived. [Update note: Another Livingstone manuscript from the period, Notebook III (22 July-7 October 1871; pages [45]-[47], [50]-[52], [77]-[81]), also covers the period in question and also contains entries for many of the missing dates, thereby further reinforcing the point that some of the original diary fragments have not survived.]

History of the Manuscript Top ⤴

From Africa to England (1871-74) Top ⤴

After Stanley’s departure in February 1872, Livingstone kept a selection of his pocket-books (I to XIII, plus one from a previous expedition) in a box at Ujiji, an Arab depot on the eastern shore of Lake Tanganyika. These pocket-books pre-dated Stanley’s arrival and served as back-ups for the Unyanyembe Journal (1866-72), which Livingstone had entrusted to Stanley.

The pocket-books remained at Ujiji after Livingstone’s death in March 1873 and were recovered by the British explorer Verney Lovett Cameron in February 1874 (Cameron 1877a,1:240-41). Cameron sent the pocket-books back to England, where Horace Waller, Livingstone’s friend and posthumous editor, received them on behalf of the Livingstone family in January 1875. Ultimately, Waller used the Unyanyembe Journal and the four pocket-books Livingstone filled during and after his time with Stanley as the primary sources for the Last Journals (1874), but the initial thirteen pocket-books arrived too late to be of use to Waller (Helly 1987:64-65, 130).

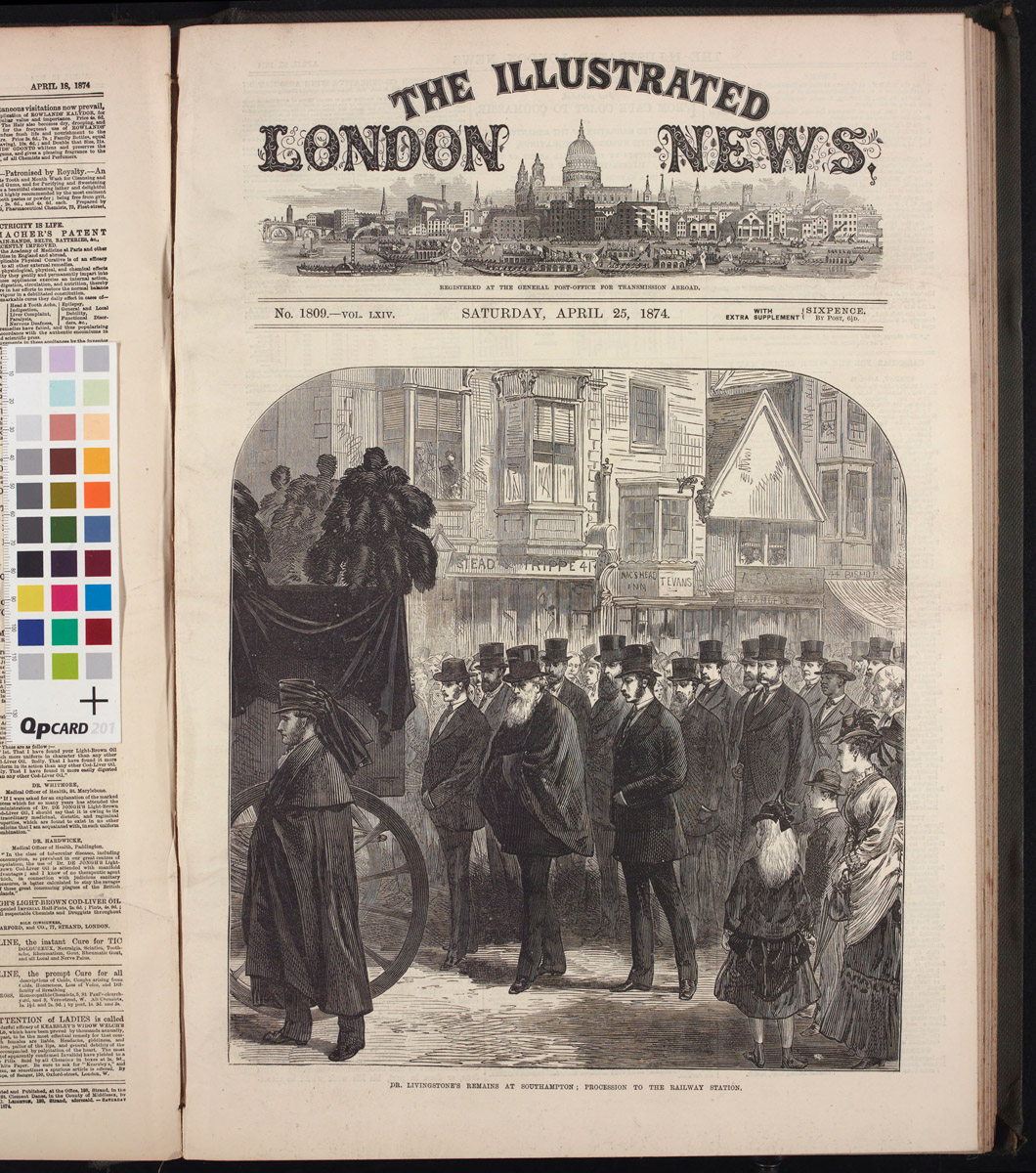

Dr. Livingstone's Remains at Southampton; Procession to the Railway Station. Illustration from Illustrated London News (25 Apr. 1874). Copyright National Library of Scotland. Creative Commons Share-alike 2.5 UK: Scotland

Curiously, Livingstone did not leave the 1870 and 1871 Field Diaries in the box at Ujiji when he embarked on his final journey, although the diaries – like the pocket-books left at Ujiji – predated the Stanley meeting and duplicated material in the Unyanyembe Journal. Rather, Livingstone took the diaries with him, and they were in his "battered tin travelling-case" when he died. Eventually, these diaries along with "the field diaries dating from Stanley’s departure in March 1872 to Livingstone’s last entry in April 1873" accompanied Livingstone’s body back to England (Waller, in Livingstone 1874,1:v; Helly 1987:65).

Production of the Last Journals (1874) Top ⤴

Livingstone’s decision to take the 1870 and 1871 Field Diaries with him ensured that they were available – unlike the thirteen pocket-books that preceded them – to Waller when producing the Last Journals. In fact, the Last Journals includes a facsimile by Cooper Hodson of page CXVII of the 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1874,2:opposite 114; learn more about the facsimile). Waller’s introduction also details Livingstone’s method for producing this diary: "for pocket-books gave out at last, and old newspapers, yellow with African damp, were sewn together, and his notes were written across the type with a substitute for ink made from the juice of a tree" (Waller in Livingstone 1874,1:iv).

Waller also twice refers to his success in transcribing the text of these newspapers:

"An old sheet of the Standard newspaper, made into rough copy-books, sufficed for paper in the absence of all other material, and by writing across the print no doubt the notes were tolerably legible at the time. The colour of the decoction used instead of ink has faded so much that if Dr. Livingstone's handwriting had not at all times been beautifully clear and distinct it would have been impossible to decipher this part of his diary." (in Livingstone 1874,2:114n.)

"To Miss [Agnes] Livingstone and to the Rev. C. A. Alington I am very much indebted for help in the laborious task of deciphering this portion of the Doctor’s journals. Their knowledge of his handwriting, their perseverance, coupled with good eyes and a strong magnifying-glass, at last made their task a complete success." (in Livingstone 1874,1:iv)

Yet these claims must be qualified and clarified. Although the references to "old newspapers, yellow with African damp," "the Standard newspaper," and the "decoction used instead of ink" point primarily to the 1871 Field Diary, Waller indeed had both the 1870 and 1871 Field Diaries available to him. Agnes Livingstone transcribed the entire 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870b-k, 1871a-b, 1871e) and the first half of the first page of the 1871 Field Diary (1871f:CII) – while C.A. Alington transcribed the first third of the 1871 Field Diary (1871f:CII-CXXIII). These transcriptions, although faulty and incomplete, were then typeset and, after much revision, became the basis of the Last Journals.

A page from C.A. Alington's transcription of the 1871 Field Diary (corresponding to Livingstone 1871f:CXIII). Images copyright The Bodleian Library, University of Oxford. Used by permission.

Both Agnes Livingstone’s and a portion of C.A. Alington’s transcriptions survive and are held among the Waller Papers at the Weston Library at Oxford University (Mss. Afr. s. 16/6), as are both the original and revised versions of the typeset transcriptions (Waller Papers, Mss. Afr. s. 16/6-8 passim). Comparison of the original 1871 Field Diary, Alington’s transcription, the Unyanyembe Journal, and the published Last Journals shows that, despite assertions to the contrary, Waller used only the first third of the 1871 Field Diary (i.e., that part transcribed by Alington) for the final text; then the Unyanyembe Journal to cover the rest of Livingstone’s time in Nyangwe. In other words, after the last diary entry transcribed by Alington, 30 April 1871, the text of the Last Journals makes a radical departure from the text the 1871 Field Diary, and there is no evidence to suggest that the last two-thirds of the 1871 Field Diary were ever transcribed before the current critical edition. [Update note: Livingstone Online has now also published a separate multispectral critical edition of the 1870 Field Diary.]

1874 to Present Top ⤴

▲ 1. The Nyangwe Segment. The history of this segment (Livingstone 1871f) is difficult to reconstruct, being both complex and not fully documented. After Waller completed his work with these leaves in 1874, it is most likely that the leaves (with one exception) passed to the Livingstone family. The family then gifted these leaves to the Scottish National Memorial to David Livingstone (now the David Livingstone Centre), although the date is uncertain. The gift might have been made as early as the late 1920s when Anna Mary Livingstone Wilson (then Livingstone’s only surviving daughter) and Hubert F. Wilson (Livingstone’s grandson) began to "gather & preserve for future generations all the principal relics of Livingstone in the Birth place at Blantyre" (MacNair 1928). However, it is also possible that the gift was made after Anna Mary Livingstone’s death in 1939, or even after the end of World War II (Wilson 2011). The leaves remained at Blantyre until at least 1975 (Cunningham 1975).

The leaf that contains pages CXVI (recto) and CXVII (verso) represents the exception to this history. As noted above, the Last Journals include a partial facsimile of CXVII. It appears that after the Journals was published, this leaf entered the possession of John Murray III, the publisher, and remained in the Murray family until early 1929. At that point, Sir John Murray V, the grandson of the publisher, agreed to provide this leaf together with two manuscript volumes of Livingstone’s Missionary Travels (see Clendennen and Cunningham 1979:265) to the Memorial "on indefinite loan" noting that "the bit of newspaper" was "fading" and would "have to be kept in a dark place when not actually being examined" (Murray V 1929). The Memorial formally received the leaf on 16 August 1929 (Cunningham 1975).

The David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre, 2010. Courtesy of the David Livingstone Centre.

When in 1972 John Murray VI requested the return of the leaf – which he described as "[o]ne frame containing a portion of the journal written in Africa on a sheet of the Standard newspaper with juice from local plants instead of ink (a rather curious item)" (Murray VI 1972) – representatives of the Memorial asked for a delay in the return. A lengthy correspondence ensued, as Murray pressed his request. The exchanges between Murray and the Memorial, which still exist in the DLC "Correspondence Archives," culminated in Murray being informed that the leaf had been "‘misplaced’" (Cunningham 1975), and as late as 2009 John Murray VII indicated that he could not locate any record of what happened to the leaf (Murray VII 2009).

Yet evidence elsewhere indicates that by the late 1970s the John Murray Archive in London not only held the "‘misplaced’" leaf, but, intriguingly, all the other leaves that make up the Nyangwe Field Diary proper. This evidence suggests that Memorial representatives eventually found the leaf and provided it to the National Library of Scotland, where the all the leaves of the diary were copied for the NLS as part of the Livingstone Documentation Project (Clendennen and Casada 1981). As a result, for a time the NLS held the complete set of originals alongside photocopies under the shelfmark MS. 10717. Finally, the NLS – erroneously it appears – handed the entire set of original leaves to the John Murray Archive: "The originals, at one time part of [the MS.10717] deposit, have since been returned to the owners, John Murray, publishers, London” (Anon. 1992,8:157).

The National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, 2010. Courtesy of the National Library of Scotland.

These details, in turn, correspond to the information in the Livingstone Catalogue of Documents. The Catalogue places the leaves in the Murray Archive while also noting that they were previously held by the Memorial (Clendennen and Cunningham 1979:277, Field Diary 37). Unfortunately, the relevant portion of the "Slip Catalogue" – i.e., the original notes which Gary Clendennen and Ian Cunningham used to produce the relevant entry in Catalogue of Documents, and which Clendennen was kind enough to copy for Adrian S. Wisnicki in 2010 – provides no further information.

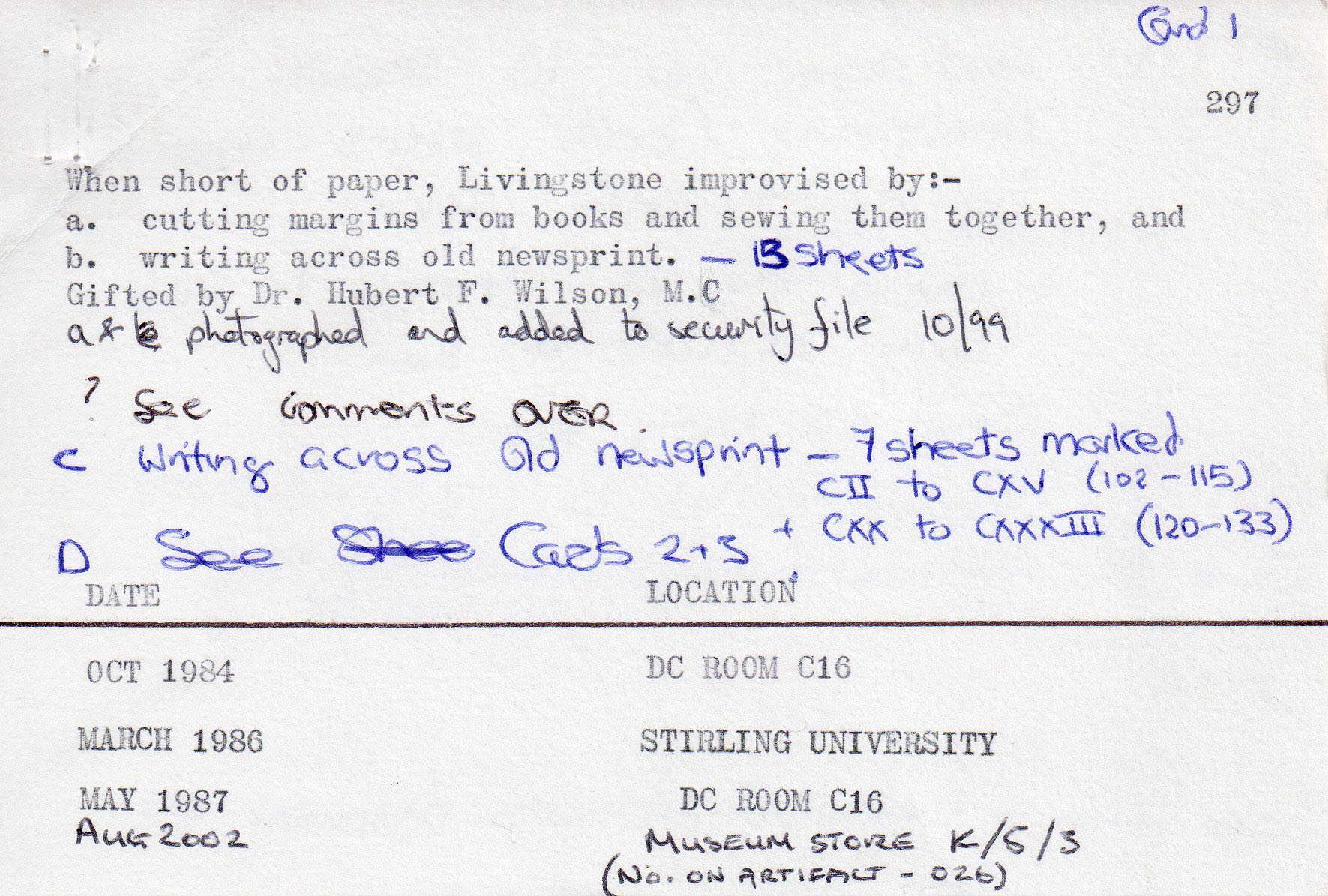

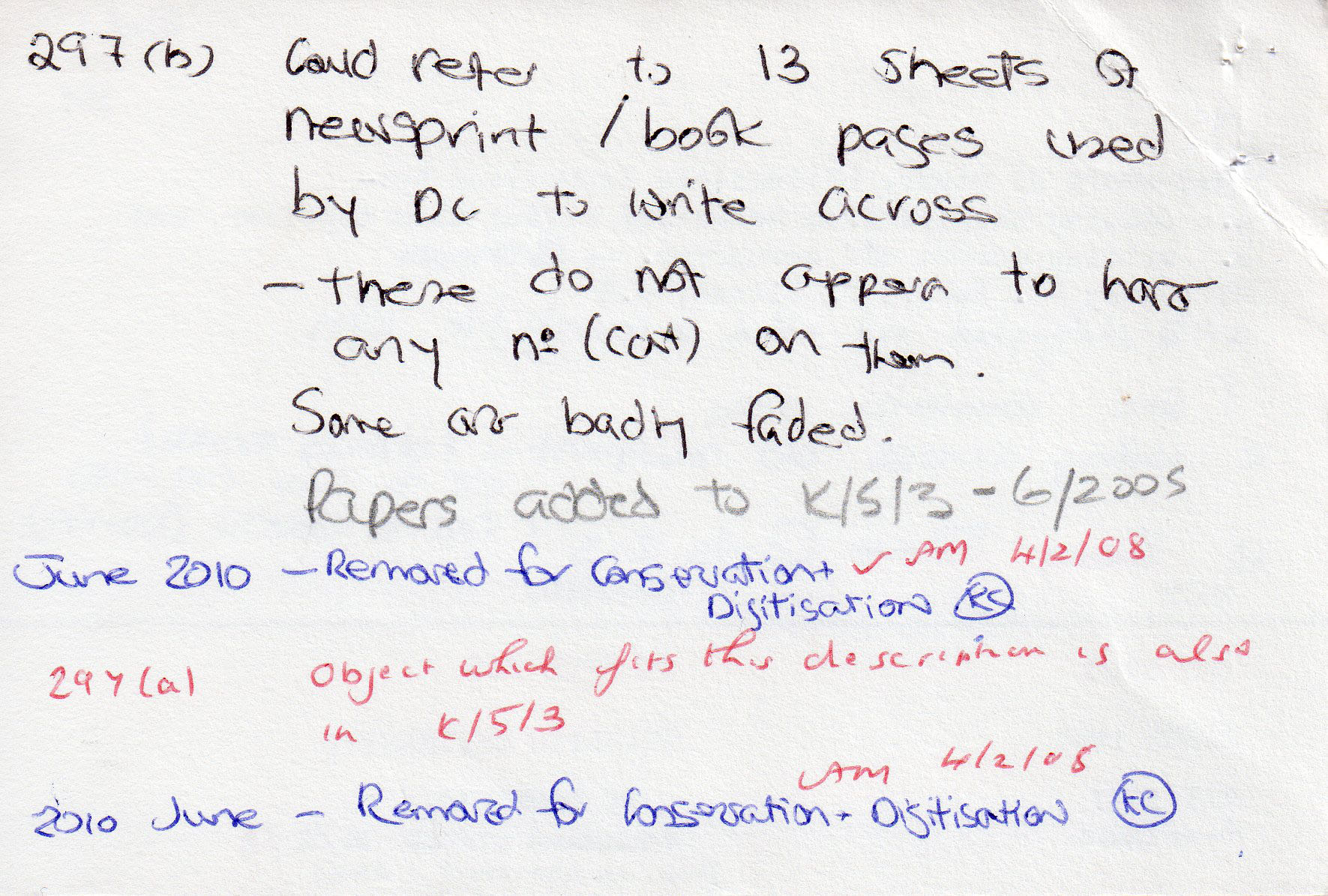

Whatever the case, an attempt in 2009 to find the 1871 Field Diary in the John Murray Archive (which the National Library of Scotland purchased in 2005) failed to discover either the leaves or any information on their whereabouts. The diary was "rediscovered" at the David Livingstone Centre (as the Memorial has also been called since 1999) only after an extensive search by Anne Martin, a volunteer archivist, at the behest of Adrian S. Wisnicki, then director of the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project and now also director of Livingstone Online. Martin’s search located half the diary leaves under the shelfmark 297b (including the Murray leaf), with the other half being found in a second, undocumented location (now shelfmark 297c). As a result, the only clue to the full history of the diary from 1975 to 2009 comes from the 297b card index entry that records that these leaves (Livingstone 1871f:CXVI-CXIX and CXXXII [v.2]-CLXIII) as well as two from 1870 Field Diary (Livingstone 1870f and 1871a) were gifted to the Centre by Hubert F. Wilson at some indefinite point (Wilson, Livingstone’s grandson, died on 9 February 1976).

David Livingstone Centre card index entry 297a and 297b, updated to include 297c and 297d (recto: top; verso: bottom), 2010. Copyright David Livingstone Centre. Object images used by permission. May not be reproduced without the express written consent of the National Trust for Scotland, on behalf of the Scottish National Memorial to David Livingstone Trust.

The entry also indicates that the leaves were transferred for conservation to Stirling University in March 1986, then returned to the Centre in May 1987, where they have remained until the present day. It seems likely that the additional leaves (1871f:CII-CXV, CXX-CXXXIII [v.1]) followed a similar trajectory as they have received the same conservation treatment as the leaves under the shelfmark 297b. Yet the card index entry fails to resolve how, when, or why in the late 1970s and/or early 1980s the 1871 Field Diary was transferred from the Centre to the Murray Archive and back again. It is also not clear why the verso of the card index entry includes a handwritten addition recording "13 sheets of newsprint / book pages" when there are only 12 leaves under the 297b shelfmark. Consequently, at this stage it is possible to provide only a partial history of these leaves; significant gaps must remain until further evidence emerges.

[Update note: Since the first edition publication of the present edition in 2012, the David Livingstone Centre has restored the leaf with pages CXVI (recto) and CXVII (verso) to the John Murray Archive at the National Library of Scotland.]

▲ 2. Additional Diary Pages. These leaves (Livingstone 1870k, 1870l, 1870m) have a much simpler, if also partly undocumented history. The leaves were probably among "the makeshift papers relating to the period in 1871 before Stanley arrived" that accompanied Livingstone’s body to England in 1874 (Helly 1987:65). Henceforth, the Livingstone family presumably took possession of the leaves.

a. Livingstone 1870k. In 1965, Hubert F. Wilson, the grandson of David Livingstone, gifted the leaves that constitute this item along with other parts of the 1870 Field Diary (1870e, 1870i, 1870k, 1871b, 1871e) as well as Livingstone's 10 March 1870 "Retrospect" (1870a) to the National Library of Scotland. The leaves have remained there ever since (Clendennen and Cunningham 1979:277, Field Diary 38).

b. Livingstone 1870kl. At some point this leaf passed from the Livingstone family to the David Livingstone Centre, although there is no direct evidence to support or undermine this assertion. Today the leaf resides between the pages of another Livingstone copy-book relating to the same period (Clendennen and Cunningham 1979:276, Field Diary 33).

c. Livingstone 1870m. At some point, probably in the late-nineteenth century, these leaves passed from the Livingstone family to Horace Waller’s permanent possession and were among his papers when he died. "The Bodleian Library Record" of April 1940, which relates to the Waller Papers as a whole but does not discuss these specific leaves, notes that "This collection of letters and private papers belonged to the Rev. Horace Waller (1832-1896) and has been presented to Bodley by his daughters, Lady Hunt and Miss Grace Waller." Today the leaves are kept at the Weston Library, Oxford University (Clendennen and Cunningham 1979:277, Field Diary 39).

Works Cited Top ⤴

[View the Livingstone Spectral Imaging Project's full bibliography.]

Anon. 1992. National Library of Scotland Catalogue of Manuscripts Acquired Since 1925. Vol. VIII. Edinburgh: HMSO.

Cameron, Verney Lovett. 1877a. Across Africa. 2 vols. London: Dalby, Isbister & Co.

Clendennen, Gary W., and Ian C. Cunningham. 1979. David Livingstone: A Catalogue of Documents. Edinburgh: National Library of Scotland for the David Livingstone Documentation Project.

Clendennen, Gary W., and James A. Casada. 1981. "The Livingstone Documentation Project." History in Africa 8: 309-17.

Cunningham, William. 1975. Letter to John G. Murray. 5 May 1975. Correspondence Archives. David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre.

Helly, Dorothy O. 1987. Livingstone's Legacy: Horace Waller and Victorian Mythmaking. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press.

Livingstone, David. 1866-72. Unyanyembe Journal. 28 Jan. 1866-5 Mar. 1872. 1115. David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1870a. Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal. 10 Mar. 1870. MS. 10703, ff. 40-43. National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1870b. Fragment of 1870 Field Diary. 17, 24 Aug. 1870. 297a. David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1870c. Fragment of 1870 Field Diary (I-IV). 18, 24 Aug. 1870. Add. MS. 50184, f. 169. British Library, London, England.

Livingstone, David. 1870d. Fragment of 1870 Field Diary. 25 Aug.-8 Oct. 1870. Transcribed by Agnes Livingstone. Waller MSS. Afr. s. 16.6. Bodleian Library. Weston Library, Oxford, England.

Livingstone, David. 1870e. Fragment of 1870 Field Diary (X-XIII). 10 Oct. 1870. MS. 10703, ff. 1-2. National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1870f. Fragment of 1870 Field Diary (XIV). 13 Oct. 1870. 297b. David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1870g. Fragment of 1870 Field Diary. 16 Oct. 1870. Transcribed by Agnes Livingstone. Waller MSS. Afr. s. 16.6. Bodleian Library. Weston Library, Oxford, England.

Livingstone, David. 1870h. Fragment of 1870 Field Diary (XVII-XX). 19-31 Oct. 1870. 297d. David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1870i. Fragment of 1870 Field Diary (XXI-LXI). 3-15 Nov. 1870. MS. 10703, ff. 3-23. National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1870j. Fragment of 1870 Field Diary (LXII-LXIX). 22 Nov.-10 Dec. 1870. 297e. David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1870k. Fragment of 1870 Field Diary (LXX-LXXV). 12-23 Dec. 1870. MS. 10703, ff. 24-26. National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1871a. Fragment of 1870 Field Diary (LXXVI). 16 Jan. 1871. 297b. David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1871b. Fragment of 1870 Field Diary (LXXVIII-LXXXVII). 24 Jan.-19 Feb. 1871. MS. 10703, ff. 27-31. National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1871c. Letter to Horace Waller. 5 Feb. 1871. Peter Beard Studio, New York, New York, USA.

Livingstone, David. 1871e. Fragment of 1870 Field Diary (LXXXVIII-CI). 21 Feb.-22 Mar. 1871. MS. 10703, ff. 32-35. National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1871f. Fragment of 1871 Field Diary (CII-CLXIII). 23 Mar. 1871-11 Aug. 1871. 297b, 297c. David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1871k. Fragment of 1871 Field Diary. 11 Aug. 1871-9 Sept. 1871. MS. 10703, ff. 36-39. National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1871l. Fragment of 1871 Field Diary. 28 Sept. 1871-7 Oct. 1871. 1120b. David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre, Scotland.

Livingstone, David. 1871m. Fragment of 1871 Field Diary. 23 Oct. 1871-3 Nov. 1871. Waller MSS. Afr. s. 16.1, f. 172. Bodleian Library. Weston Library, Oxford, England.

Livingstone, David. 1874. The Last Journals of David Livingstone in Central Africa, from 1865 to His Death, edited by Horace Waller. 2 vols. London: John Murray.

MacNair, James. 1928. Letter to John Murray V. 21 Dec. 1928. Correspondence Archives. David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre.

Murray, John, V. 1929. Letter to James MacNair. 19 Mar. 1929. Correspondence Archives. David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre.

Murray, John, VI. 1972. Letter to William Cunningham. 11 Sept. 1972. Correspondence Archives. David Livingstone Centre, Blantyre.

Murray, John, VII. 2009. Email to Adrian S. Wisnicki. 1 July 2009. Private correspondence.

Wilson, Neil. 2011. Email to Adrian S. Wisnicki. 22 Aug. 2011. Private correspondence.

![Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from Livingstone's 1871 Field Diary (Livingstone 1871k:[5] pseudo_v1), detail. Copyright David Livingstone Centre and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_013723_0001-new-carousel_0.jpg)

![Processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's "Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal" (Livingstone 1870a:[3] pseudo_v4_BY), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 Processed spectral image of a page from David Livingstone's "Retrospect to be Inserted in the Journal" (Livingstone 1870a:[3] pseudo_v4_BY), detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_000211_0003_pseudoBY_940_by_592-carousel.jpg)

![David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, [1869], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland: CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0 David Livingstone, Map of Central African Lakes, [1869], detail. Copyright National Library of Scotland: CC BY-NC-SA 2.5 SCOTLAND and Dr. Neil Imray Livingstone Wilson: CC BY-NC 3.0](https://livingstoneonline.org:443/sites/default/files/section_page/carousel_images/liv_003006_0001-new-carousel_0.jpg)